Initially, Samuel French Morse's fourth book of poems seems to hold few surprises. Morse is still the self-described "New England Poet"; he is still the skilled verbal craftsman; he is still pre-eminently the nature poet. Much in this book seems as it has always been.

Much, but not all. Morse's perception of his own role as nature poet — his distinction between the observed natural object outside and the felt emotional experience within — has never been sharper. In a supremely apt passage, which he has chosen for the epigraph of his book, Morse adduces the authority of Thoreau to make the point for him. "We are not wholly involved in Nature," Thoreau writes. "I...am sensible of a certain doubleness by which I can stand as remote from myself as from another. However intense my experience, I am conscious of the presence and criticism of a part of me, which, as it were, is not a part of me, but spectator, sharing no experience, but taking note of it."

Spectator, but also sharer; detached observer, but also involved in what he observes; recorder, but also lover of what he records: Morse turns Thoreau's abstract polarities into the felt experience of poems.

At the one pole the observer, recorder. Many of Morse's poems seem impersonal, as if the poet were, in Thoreau's language, standing as remote from himself as from another. These poems have an austere, wintry quality about them, for as observer Morse is tough-minded. He knows nature, knows botany, geology, ornithology, natural history. And he knows some somber truths about nature. He knows that however much we pretend, we cannot possess our earth, "piecing it out in crop and pasture land." That shadow-pretense has lasted "only until the fences rotted, like those dreams/of affluence that wasted all your streams." He knows that nature brooks no special law for modern man. We, too, face our time-doom, as subject to extinction as the hosts of passenger pigeons that once seemed numberless, as impermanent as the now extinct aboriginal tribes of the Northeast. Therefore, If once againwe court extinction, though the morning skylooks clear enough, we ought to know the wordsfor quarry and for hunters flown so highthey never see their prey — like birds, like men.

But there is that other pole too, the obverse side of Thoreau's "doubleness." For like Thoreau, Morse also is necessarily "involved in Nature," and he, too, celebrates what he observes. Not that he wears his praise on his sleeve. He is, after all, a "New England poet"; his characteristic voice is one of understatement, obliqueness. But though chary of over-praise, he does nonetheless praise. "The world is there," he concludes, "and likely will be when/we all are gone."

—The early morning lightmore certain than the means we make our waysshould signify as much to other menand give them, whether we were wrong or right,as good a reason for a kind of praise.

Another "New England poet," Robert Frost, once wrote his own book of "sequences," 12 poems, one for each month. It began with January and ended with December. From Snowto Snow, Frost called it. Morse adopts something of the same format, but the difference is significant. Morse arranges his sequences to go not from snow to snow but from summer to summer, from sun to sun. He records the autumnal, but he praises the vernal. He seems to have adopted the working principle of another nature poet, Thomas Hardy:

Let me enjoy the earth no lessBecause the all-enacting MightThat fashioned .forth its lovelinessHad other aims than my delight.

THE SEQUENCESBy Samuel French Morse '36Northeastern University, 1978.45 pp. $2.25

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

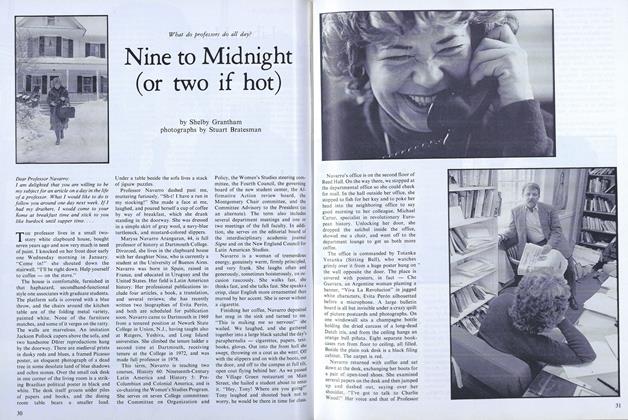

FeatureNine to Midnight (or two if hot)

March 1979 By Shelby Grantham -

Feature

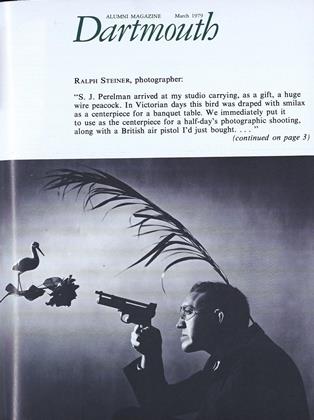

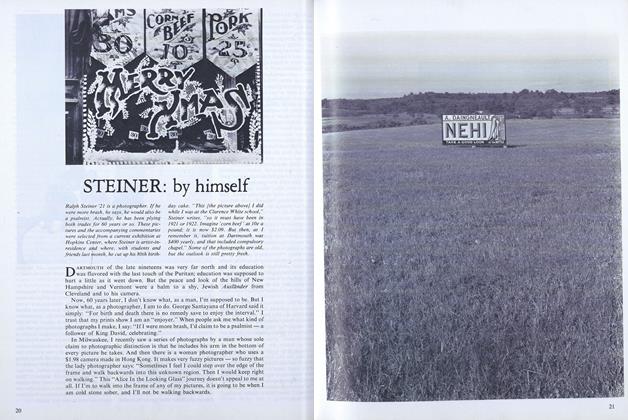

FeatureSTEINER: by himself

March 1979 -

Books

BooksNotes on lost causes and an enlistment against Nature, as brave as it was brief.

March 1979 By R. H. R. -

Article

ArticleWinter Carnival Blues

March 1979 By Biĺ Conway '79 -

Article

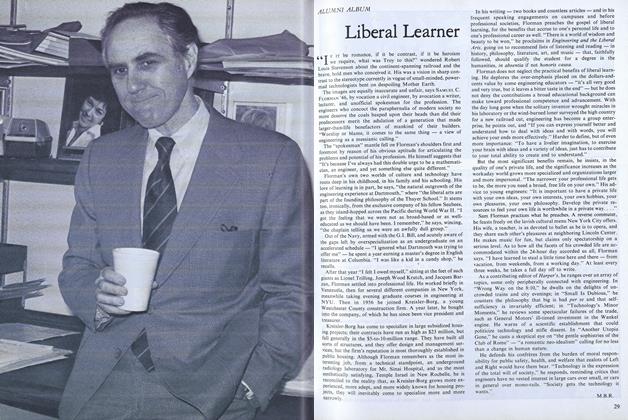

ArticleLiberal Learner

March 1979 By M.B.R. -

Class Notes

Class Notes1974

March 1979 By STEPHEN D. SEVERSON

R. H. R.

-

Article

ArticleNotes on a Distinguished Defendant and the Supreme Court’s Great non-decision

DEC. 1977 By R. H. R. -

Books

BooksLooking Back

April 1979 By R. H. R. -

Books

BooksMythogenic

JAN./FEB. 1980 By R. H. R. -

Books

BooksNot for Art's Sake

APRIL 1982 By R. H. R. -

Books

BooksSleuthing

APRIL 1982 By R. H. R. -

Books

BooksMan in the Cambric Mask

JUNE 1982 By R. H. R.

Books

-

Books

BooksShelflife

Mar/Apr 2006 -

Books

BooksA BRIEF HISTORY OF MEDICINE IN MASSACHUSETTS.

MARCH 1931 By Frederic P. Lord -

Books

BooksGUIDANCE IN CATHOLIC COLLEGES AND UNIVERSITIES. Edited

October 1949 By Howard F. Dunham '11 -

Books

BooksGEOCHEMISTRY OF BERYLLIUM AND GENETIC TYPES OF BERYLLIUM DEPOSITS.

OCTOBER 1966 By JOHN B. LYONS -

Books

BooksTHE COLLECTION OF FEDERAL OLD-AGE BENEFITS TAXES AND THE RECORDING OF WAGES BY MEANS OF THE STAMP PASS BOOK SYSTEM.

December 1936 By Lloyd P. Rice -

Books

BooksINSTRUCTIONS FOR PRACTICAL LIVING AND OTHER NEO-CONFUCIAN WRITINGS

FEBRUARY 1964 By TIMOTHY J. DUGGAN