Most of us, after an initial mental blank, can recall some of the books of our childhood—either because they enchanted us, or because they terrified us, or for some other (and doubtless fascinating) reasons. We prompted some of Dartmouth's faculty to do just that this month, and the range of the memories they called up—from the whimsical to the terrifying—reminded us again just how rich and various a thing childhood is.

Here, then, to spark your own recollections, are eight accounts of a sentimental journey back through time in search of the literary talismans of childhood. We have turned up some old favorites—Oz and Arthur, Uncle Remus and the Little Match Girl—in the company of such unanticipated characters as Loeb and Leopold and Lazarillo de Tormes; and some of our authors spent many young hours "traveling" in realms of gold Keats never thought of. We hope that this excursion into the tender past will, enhance that festive nostalgia that lies at the heart of the Yuletide season. Happy Christmas to all!

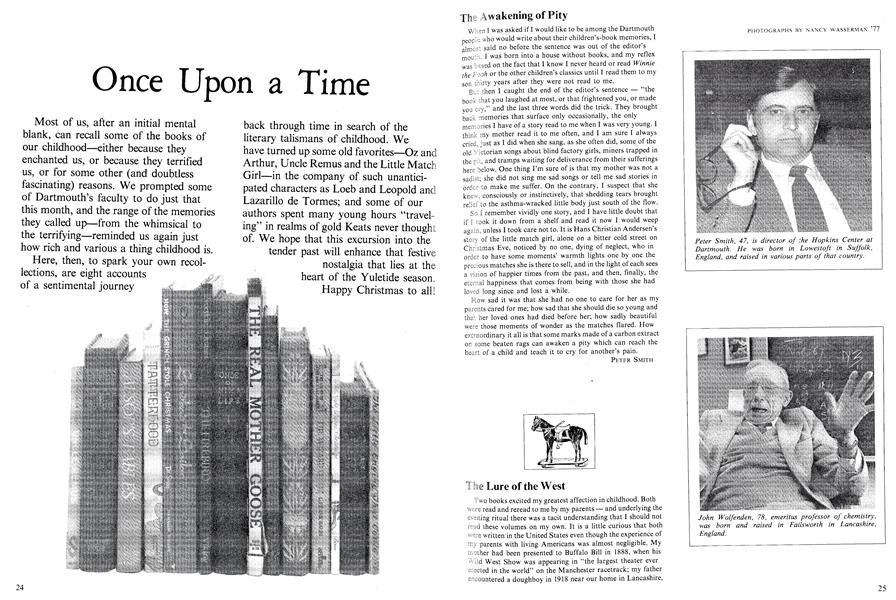

The Awakening of Pity

When I was asked if I would like to be among the Dartmouth people who would write about their children's-book memories, I almost said no before the sentence was out of the editor's mouth. I was born into a house without books, and my reflex was based on the fact that I know I never heard or read Winniethe Pooh or the other children's classics until I read them to my son thirty years after they were not read to me.

But then I caught the end of the editor's sentence - "the book that you laughed at most, or that frightened you, or made you cry," and the last three words did the trick. They brought back memories that surface only occasionally, the only memories I have of a story read to me when I was very young. I think my mother read it to me often, and I am sure I always cried, just as I did when she sang, as she often did, some of the old Victorian songs about blind factory girls, miners trapped in the pit, and tramps waiting for deliverance from their sufferings here below. One thing I'm sure of is that my mother was not a sadist; she did not sing me sad songs or tell me sad stories in order to make me suffer. On the contrary, I suspect that she knew, consciously or instinctively, that shedding tears brought relief to the asthma-wracked little body just south of the flow.

So I remember vividly one story, and I have little doubt that if I took it down from a shelf and read it now I would weep again, unless i took care not to. It is Hans Christian Andersen's story of the little match girl, alone on a bitter cold street on Christmas Eve, noticed by no one, dying of neglect, who in order to have some moments' warmth lights one by one the precious matches she is there to sell, and in the light of each sees a vision of happier times from the past, and then, finally, the eternal happiness that comes from being with those she had loved long since and lost a while.

How sad it was that she had no one to care for her as my parents cared for me; how sad that she should die so young and that her loved ones had died before her; how sadly beautiful were those moments of wonder as the matches flared. How extraordinary it all is that some marks made of a carbon extract on some beaten rags can awaken a pity which can reach the heart of a child and teach it to cry for another's pain.

PETER SMITH

The Lure of the West

Two books excited my greatest affection in childhood. Both were read and reread to me by my parents and underlying the evening ritual there was a tacit understanding that I should not read these volumes on my own. It is a little curious that both were written in the United States even though the experience of my parents with living Americans was almost negligible. My mother had been presented to Buffalo Bill in 1888, when his Wild West Show was appearing in "the largest theater ever erected in the world" on the Manchester racetrack; my father encountered a doughboy in 1918 near our home in Lancashire, and his remark, "I'm from Omaha," had vowel sounds that enchanted my father.

Uncle Remus was read to me by my mother in an accent that would not have been recognized south nor indeed north of the Mason-Dixon line. Although I was fascinated by Brer

Rabbit, the conversation between Uncle Remus and "the little boy" that prefaced every story was the most precious part of every reading. No one seemed to me as entirely lovable as Uncle Remus.

My father's choice was Artemus Ward, His Book by Charles Farrar Browne, and, had he lived long enough, he would have enthusiastically joined my literary pilgrimage to the offices of the Coos County Democrat in Lancaster, New Hampshire. Browne's humor is perhaps an acquired taste, and indeed when I read Artemus Ward for myself later I found I was impatient with his eccentric spelling. It might be hard to find a less socially responsible painter of the American scene, but my father found Browne's sense of the absurd immensely congenial. His delight was infectious, and those evening readings of well over 60 years ago are still a delight to recall.

JOHN WOLFENDEN

Of Postage Stamps and Knotted Things

The first book that I can remember is Scott's postage stamp album, which was very important to me visually. During the Depression it cost a dollar, and I remember carrying it home, with one of those huge packets of stamps, a 500-assortment, for, oh, five cents. I remember going through and picking out

stamps and pasting them in according to the various countries. I think it influenced me a great deal, because a number of my recent collages have to do with cutting paper and inserting smaller papers into them; and I hinge, too, on my new papers a throwback to hinging stamps onto the page. Later on I got a more elaborate postage stamp album, in which you slipped the stamps into pockets, and I've also done a number of collages where slipping in takes place. So here I am at 54, using some of the little techniques that I was involved with when I was ten years old.

The Boy Scout Handbook was important, too - merit badges, second-class, first-class, how to do this, how to do that. I remember that the qualifications for the lifesaving merit badge were always so difficult for me to read and to execute that I never got to be an Eagle Scout. And I remember visual

illustrations of twisting dough on sticks - you know, on the 14-mile hike. Little things like that. And the knots were very

important. A number of years ago I gave a knot problem in one of my design classes, which was to make a knot but hide both ends so you never knew where the beginning or the end was. We had some fantastic solutions.

As far as actual books go, I remember one from the third or fourth grade, a little story that was used as a textbook, and I think it was Arlo, or Little Arlo. It had something to do with a young boy and the prince-and-pauper idea, I think. But one part of it had to do with camping out, and the idea of cool spring water, and it aroused an adventure thing in my spirit that later on was combined with Albert Payson Terhune and all those dog stories Lad and Bruce which sort of went hand-in-hand with Richard Halliburton. He was the one who climbed the Matterhorn and all of that and was lost in a junk trying to cross the Pacific. They went along with Travels witha Donkey and An Inland Voyage, the two books I liked very much by Robert Louis Stevenson. Somewhere along in this whole mess, of course, were King Arthur and the knights. Not Malory, but a very simplified King Arthur and the Knights of the Round Table, a library book that I read in about the fifth grade.

I think the first picture book that really moved me was Thomas Craven's One Hundred Masterpieces of Art. It was the art book of the day. Now, of course, we have all the great Abrams coffee table books; but in those days, One HundredMasterpieces was the crowning achievement in art

reproduction. It was a library book too. (We had a marvelous, Carnegie-endowed library in New Britain, Connecticut.) Then, in junior high, I ran into some remarkable teachers, who were all in love with poetry. From the four of them I got Edna St. Vincent Millay, Sara Teasdale, Wordsworth, and

Vachel Lindsay, a pretty terrific assortment. Miss Cahill used to get up at the beginning of every class and recite every day for a year the same poem and she never killed it. Miss Hughes always started her class with a very famous quote (some of them were absolutely meaningless to me at the time). Miss Smith, the librarian, when she found out you were interested, would take you to her desk and read or recite to you, often Wordsworth. I remember especially "Composed Upon Westminster Bridge." And the other teacher found out that I liked poetry, I guess through Miss Smith, and started showing me Vachel Lindsay and Carl Sandburg; and then one day, on a Saturday, she took me to New Haven to a matinee with her niece and another teacher, and we saw Maurice Evans and Helen Hayes in TwelfthNight. That was fantastic.

Those women started my whole affair with poetry, which I have continued to this day. Literature is extraordinarily meaningful to me, even though I'm a visual artist. It's very seldom that I read a novel, but poetry is very important. To this day, in my art classes I read my students poetry.

VARUJAN BOGHOSIAN

You Can't Get Anywhere from Now

I could never puzzle out why seven trains went out but only six came back. Was there a warehouse down there in Market Drayton, crammed with first- and third-class carriages (smoking and non-smoking), guard's vans and engines kept in reserve for some unimaginable war? Or did the trains sneak back at midnight unannounced, mail-bags perched in the dusty seats and milk-churns morris-dancing in the corridors? Did they simply disappear? What had happened to the engine-drivers in their buffeted leather caps and the guards with silver whistles? Had anyone noticed? Did anybody know? Informative as it was, bulging with destinations from Zeals to Aberystwyth (no Sunday service), the ABC Railway Directory could not tell me.

That a book too thick to grasp in one eight-year-old hand kept silent as Sabbath mornings about the urgent problem of the evanescent trains shook my confidence in authority. But not for long. My 981-page paper horse could take me from Thurso (change at Georgemas Junction, a remote hospice for dragonslaying priests) to piratical Penzance. It could take me to Burslem, Splott, or Bat and Ball. It could take me back to my native, almost unspellable and totally unpronounceable Welsh village. It could take me, at its longest-winded canter, to Prague (Woodrow Wilson). It could take me by four different ways to Wisbech, Cambs. (market-day, Thursday).

This year, I actually got to Wisbech. They sell samphire there, on fishmongers' slab. I went by car. The trains don't run now to that Fenland town: neither the Midland and Great Northern Joint Express nor the Hundred of Upwell Tramway.

One day when I wasn't looking, the thick volume with January 1951 along the cracked and concave spine, the edges of its brown paper jacket frayed with many more than one month's use, was heaved out in the company of an old L-to-R phone book and six dozen issues of the Radio Times. Most of the rural lines have been ripped up for scrap in any case, and the stations converted into charming weekend hideaways or extra storage space for overworked vendors of pneumatic tires. But I still don't know what happened to that seventh train.

LAURENCE DAVIES

Rogue on the Veranda

No single book holds for me, or rather for my nostalgia of it, the magic of El Tesoro de la Juventud, a Spanish encyclopedia that I bought, on the occasion of my ninth birthday, with the proceeds of the sale of my first calf. But, yes, there remains a single, earlier, indelible memory of how I came upon my first book and what that experience taught me about the value of the written word.

It was our household routine, when I was about three years old, to gear all our plans and energies towards the big event of the day: lunchtime. My father, a rancher, would then return from town, and with him arrived the daily newspaper. As he and I, the only two people on time, sat on the veranda to wait for the others, he would take his ease reading the newspaper. As part of our private game he would give me the international section to read." I don't remember exactly when or how I taught my self to read, but one day one of my pubescent sisters hurriedly passed by and, seeing me so intent on my "game," she laughed. To respond to her laughter I could do no less than read aloud to her something about the war (the second World War).

This startling discovery unleashed the greatest controversy at our dinner table. My mother was scandalized at the idea that I might have been reading all those dreadful things newspapers are known to print. The rest of my eight college-age brothers and sisters launched into a discussion of the merits and horrors of children's literature. Everyone agreed that children's books, printed on glossy paper and profusely illustrated with color drawings, were too expensive. Besides, I was the last of nine, and thus the purchase could not be handed down to another cycle of readers. On the other hand, the books in my father's library (which I later read) were all in the Church's Index, and the rest of the books in the household were either textbooks or rosy novels. Clearly, something had to be bought.

A traveling salesman provided the solution. He was peddling a miniature, pocketbook-sized collection of the Spanish classics, printed in miniscule letters on onionskin paper, especially edited for children - he said. Lazarillo de Tormes, that allabsorbing, "naive" picaresque tale, caused me to abandon the newspapers until very recently, when, during the Watergate affair, I rediscovered the engrossing narrative power of "all the news that is fit to print."

SARA CASTRO-KLAREN

A Dime's Worth of Wisdom

No great classic, no large tome, no expensive volume lingers in my mind as a lasting influence, even though by the time I was 14 A Tale of Two Cities, Les Miserables, and The Last of theMohicans had left vivid pictures of guillotines, sewers, and forests. It was, rather, a thin, light-blue, ten-cent paperback from E. Haldeman-Julius, publishers, of Girard, Kansas, that made a powerful impression. Many of their books cost only a nickel (including What Every Young Man Should Know AboutSex, which, upon reading, turned out to be very little). Most of these nickel and dime books were vapid but not the reprinting of Clarence Darrow's Defense of Loeb and Leopold. Richard Loeb and Nathan Leopold were two rich young Chicagoans who in the 1920s bludgeoned to death a young boy because of their misunderstanding of Nietzsche's superman ethics.

Could there be a defense of such a brutal murder? Clarence Darrow said yes, since the lives of the rich as well as the poor are solely the product of hereditary forces and environmental circumstances. All is determined, even the character of the rich and powerful. They, too, have no free will! For a 14-year-old that was a mind-wrenching thought, yet one that Darrow delivered with such Olympian compassion and ringing eloquence that for years I denied free will existed and argued that to understand all is to forgive all.

Decades later, in writing an article on "The Problem of Historical Inevitability," I discovered that there is no convincing philosophical proof that free will does not exist. But I also discovered that there was no convincing philosophical proof that free will does exist. My friends in philosophy at Dartmouth told me that even the great Wittgenstein had not resolved the problem. I found myself in a philosophical vacuum But nature abhors a vacuum! It was thus inevitable

(psychologically) that the compassionate and eloquent words of Clarence Darrow, words that cost a 14-year-old a dime, would rush in and would continue to persuade him that to understand all is to forgive all.

DAVID ROBERTS

Terrifying Tales

When I was a boy, my parents were more into telling us stories than they were in exposing us to books. My father wasn't home that often because he worked two jobs the whole time I was a kid. The only time I ever saw him was on the weekends, and usually he was so tired he had no time for us. And I can't remember my mother reading us stories. That's not to say it didn't happen; it's just that it isn't in the forefront of my mind.

But there were two stories I remember that had a scary impact on my mind for a long time. One was the story of Ichabod Crane. The headless horseman was terrifying, and the situation in which someone goes off and you don't quite know what happens to him was too. Crane was just never heard of again. Oh my god, you know, where did he go to?

And the other story, one that I first saw visually and later heard read to me, was The Wizard of Oz. When I first saw the film of that story, sometime before I was ten, I was terrified by the witch. I don't remember the actress's name, but she frightened a lot of children, and for a long time after she couldn't get any other roles. It was her character, you know, bent over, and that funny voice she had, that cackle. She just seemed so evil.

Also, strangely enough, there were rhymes - like, you know, that rhyme "Mares eat oats, and does eat oats, and little lambs eat ivy." For some reason that I've never really been able to understand, that little rhyme always frightened me. Don't even ask me why.

I was a very scary kid when I was young, the kind of child who is more affected by negative images than by positive ones. Part of it was probably because I grew up on a block with a lot of different ethnic groups on it Polish-Americans, Irish-Americans, Greek-Americans most of them lower-middleclass white people. We were the only black people on the street, and I went through a lot of verbal abuse taunts from my peers because I was black. I remember my mother once saying that the only thing white people seemed to hate more than black people was Jehovah's Witnesses. And the Jehovah's Witnesses family around the corner from us did seem to be the only ones who caught more than we did.

Then, too, I've always been influenced by sound, and that Mares-eat-oats piece has a kind of catchy little melody. I remember, too, that when I was four or five, my aunt took me to Peter and the Wolf, and I remember all the different characters that were expressed through instruments. That was the first time that my mind had been jostled into understanding that instruments could express a character. That influenced me quite a bit. I thought about that a lot.

My wife and I have always been interested in giving our children something we didn't get ourselves a sense through books of their multicultural heritage. We always include stories that are specifically about black children. Our concern really isn't bicultural, it's multicultural, because my wife is Czechoslovakian-American, and my own heritage is black, Native American, and Scottish. We have always been very much aware of how we present such a cross-section of ideas to them in books.

WILLIAM COLE

The Gift of a Book

My "early childhood" took place a long time ago, so most remembrances of that time are a bit fuzzy. I can still remember vividly, however, my first gift of a book. It happened on a memorable Christmas when the family had decided actually to light the tiny candles bedecking the Christmas tree (no chains of electric bulbs in those days), several adults standing by with buckets of water in case of catastrophe.

After we had beheld this glorious sight and the candles were extinguished, the gifts were distributed, and my first was a book from an elderly aunt entitled Around the World with the

Children. I was soon lost in the adventure of discovering that different-looking children with different customs actually lived in many far-off places that were often strange and exotic.

Who knows whether early influences really last - but the fact is that I remain a travel enthusiast. One of the bonuses of being

a biochemist has been the opportunity to visit so many interesting places and to see them through the eyes of the native biochemists, who have been hospitable in every country.

LUCILE SMITH

Peter Smith, 47, is director of the Hopkins Center atDartmouth. He was born in Lowestoft in Suffolk,England, and raised in various parts of that country.

John Wolfenden, 78, emeritus professor of chemistry,was born and raised in Failsworth in Lancashire,England.

Sculptor and Professor of Art Varujan Boghosian, 54,was born and raised in New Britain, Connecticut.

Laurence Davies, 37, adjunct professor of English,teaches the writing of fiction at Dartmouth. Born in Llanwrtyd Wells, Wales, he was raised there and in London.

Professor of Spanish and Portuguese Sara CastroKlaren, 38, was born and raised in the small village ofSabandria, in southern Peru.

Professor of History F. David Roberts, 57, was born inChang-sha, China, and raised in Seattle, Washington.

William S. Cole, 43, associate professor of music, wasborn and raised in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.

Emeritus Professor of Biochemistry E. Lucile Smith, 67,was born in Jackson, Mississippi, and raised in NewOrleans, Louisiana.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureAll the Way with J.B.A.

December 1980 By Frank Smallwood -

Article

ArticleQuirkiness to Taste

December 1980 By Dana Cook Grossman -

Class Notes

Class Notes1966

December 1980 By RICK MAC MILLAN -

Article

ArticleMetaphysical Voyager

December 1980 By Robert H. Ross ’38 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1940

December 1980 By RICHARD J. GOULDER -

Article

ArticleBut Still Homeless

December 1980 By Patricia Berry '81

Features

-

Feature

FeatureThe Conscience of Liberal Learning

NOVEMBER 1965 -

Feature

FeatureA VETERAN MOVES ON

SEPTEMBER 1983 By Brad Hills '65 -

Feature

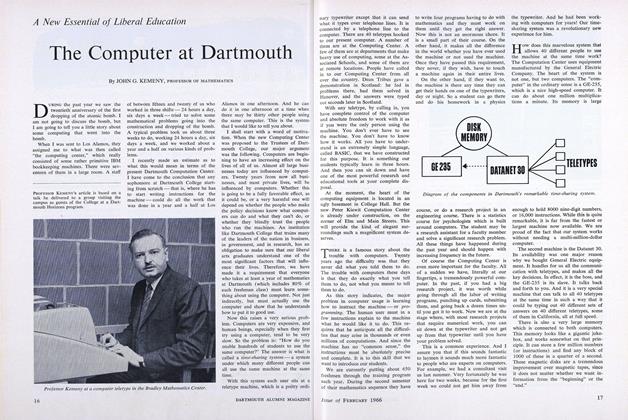

FeatureThe Computer at Dartmouth

FEBRUARY 1966 By John G. Kemeny -

Cover Story

Cover StoryLiberating the Ph.D.

OCTOBER 1970 By Robert B. Graham ’40 -

Feature

FeatureProphet of Limits

NOVEMBER 1993 By Suzanne Spencer '93 -

Feature

FeatureNotebook

Jan/Feb 2005 By THOMAS AMES JR. '74