THEODORE ROETHKE:

An American Romantic by Professor Jay Parini University of Massachusetts, 1979 203 pp. $12.50

Why yet another book on Theodore Roethke? Why, at any rate, just now? During the poet's lifetime Roethke's work received its share of attention from the literary critics, among them W. H. Auden, Stanley Kunitz, and Kenneth Burke. Since his death in 1963, however, what had been a respectable stream now threatens to become a critical torrent. Since only 1965, I count no fewer than eight major books on Roethke, to say nothing of the scores of articles, specialized studies, and ex- plications in the periodicals and literary jour- nals. Why, then, should Jay Parini, for all his critical talents, choose to enter the well- wrought labyrinth of the Roethke poems yet another time?

First, there is the stature of the poet himself. Roethke is clearly, as Parini says, "a poet of major standing in American literature." His work therefore repays not only close but repeated scrutiny. Secondly though Parini doesn t say so Roethke presents an un- deniable challenge to any critic worth his salt. He is what is commonly called a "difficult poet." His style is sometimes elliptical, his sym- bols private; his erudition is immense; his vision is often mystical, or at least idiosyncratic. Reading him aright, then, takes some doing. But Parini's most cogent reason for re- threading the maze lies in the nature of literary criticism itself. Criticism is not stasis, but process; in it there is no final solution, no single reading of any body of poems which stands im- mutable, valid everywhere and forever. As Parini writes, "No single reading of any good poet is final. Just as each new' generation of poets modifies the view of the previous one, so critics participate in an ongoing act."

Parini's result justifies his effort. Though he found a few helpful clues left behind by critics who had preceded him, clues which he scrupulously acknowledges, what Parini emerges with is his own new map of the poet's mythos. For all its modernity in its use of the techniques of psychoanalysis, for instance the poetry of Theodore Roethke, Parini finds, is best understood as a 20th-century manifesta- tion of that familiar 19th-century tradition, Emersonian Romanticism. Though Roethke "was able to assimilate the most divergent in- fluences," Parini concludes, nevertheless he "must finally be seen as the central American Romantic poet of that generation that includes Robert Lowell, John Berryman, Karl Shapiro, Richard Eberhart, and John Crowe Ransom."

"Romantic" is a notoriously slippery literary label, yet in a single chapter as admirable for its succinctness as for its breadth Parini pins his critical Proteus to the rock. "Romantic" im- plies and Roethke's poetry implicitly demonstrates he argues, a few quintessential aesthetic propositions: the true source of poetry is inspiration, not fundamental brainwork; the poet's function is to act as secular prophet; poetry is self-expression and, therefore, spiritual autobiography; poetic diction must be plain, not inflated; it is the divinely inspired faculty called "imagination" that alone permits the poet to resolve "disparate ideas and emotions into the magical unity of an image."

Above all, in its American, Emersonian manifestation, "Romantic" implies that the poet undertake what Roethke himself called "the long journey out of the self." Parini's own explanation of this journey paraphrases Emer- son: The poet "must actively seek to contact nature; ... to make the natural world an exten- sion of one's body; to connect the private self with the infinitely greater self which is transcendent." It is just such an archetypal journey that Roethke undertook, as Parini shows. The whole body of his poetry, then, can be read as documenting the steps along the way. Poem by poem, step by step, Parini reads it thus.

Parini's aim is not biographical. The man Theodore Roethke, the human being who successfully fought his way through several bouts with mental illness, the Harvard graduate student, the near-professional tennis player, the gifted teacher and conscientious faculty member at the University of Washington; none of this is fleshed out. Perhaps the book might have been the better for a few more glimpses of the flesh-and-btood man amid the bloodless abstractions of literary criticism. But Parini's aim, one recognizes, was quite otherwise: "to isolate major patterns in the work, to discover the poet's mythos, and to relate his body of writing to the Romantic tradition, its proper context." All this Parini does, and does magnificently well. That, surely, is no small ac- complishment.

Robert H. Ross ’38

Books

-

Books

BooksALL THE BEST IN SCANDINAVIA.

OCTOBER 1968 By BETTY HOEG HAGEN -

Books

BooksTHE GOSPEL OF WEALTH.

July 1962 By CLYDE E. DANKERT -

Books

BooksROAM THOUGH I MAY

April 1934 By E. B. Watson. -

Books

BooksDEXTER

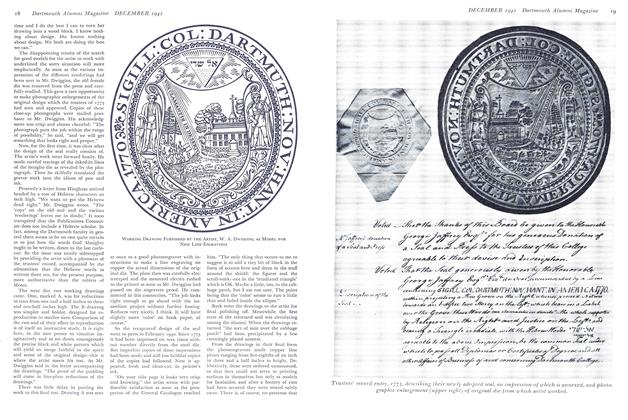

December 1941 By Herbert F. West '22 -

Books

BooksDEBRIS.

NOVEMBER 1967 By MARGARET BECK McCALLUM -

Books

BooksSOCIETY AND CULTURE.

February 1962 By RALPH P. HOLBEN