ALUMNI ALBUM

TOM Fenton, CBS News> Teheran . . . Kabul . . . London . . . Paris . . . Rome ..." A familiar face, a familiar voice in the nation's living rooms, interviewing Iranian revolutionaries, Dutch clerics, French dockworkers, Afghanistan insurgents, cockney publicans, sundry potentates; reporting on disorder and chaos the world over. It's all part of a workaday week for THOMAS T. FENTON '52, senior European correspondent for CBS News.

In the interval between the taking of the American hostages in Teheran and the eviction of American journalists for relaying the news as it happened, the backdrop was the gates of the U.S. Embassy and the sea of shaking fists and the angry faces chanting monotonously "Death to Carter," "Death to the Shah."

Fenton described the situation as "surreal." Broadcasting from Teheran some weeks after the takeover, he said, "I still find it hard to believe . . ., the world perhaps brought to the brink of war by several hundred kids, some of them no older than my daughter."

Having returned temporarily, he thought - home to England before Christmas, Fenton was awaiting a new visa for Iran when the American press corps still in Teheran was ordered to leave. In a telephone call from London in early January, he talked about those "very savvy kids" holding the embassy and their skill at recognizing-and exploiting the media event they had created, "the crass way they tried to buy us off by offering socalled 'exclusives' on secret embassy documents in exchange for unedited air time." But they were "incredibly naive" as well, he said. "They really feel that to be a code clerk is, ipso facto, to be a spy."

The tumult at the embassy gates was in extraordinary contrast to the atmosphere elsewhere in Teheran, Fenton reported. The threatening shouts he characterized as "mostly Persian hyperbole. They weren't ready to slit the throats of Americans by any means." The crowds gathering for the demonstrations tended to be friendly, even helpful, before the cameras rolled. Then, as if on cue, they would start shaking their fists, shouting angrily. A few blocks away, there was no evidence of international crisis, only of a country in economic disarray.

"It was not all for U.S. consumption, the whole television gambit," Fenton said. "It was primarily for local consumption. The country is really in bad shape. After the initial enthusiasm generated by the revolution and the overthrow of the Shah, who I really think was an outrageous monarch, then you face the hard facts of a country that's slowly falling apart. Unemployment runs 30 to 40 per cent —no one knows exactly how much and there are forces tearing the country apart. The situation is very serious with the ethnic minorities who want autonomy. Basically, Iran needed a diversion, and they had a choice between the Russians, right next door, and the Americans."

Living conditions for the international press corps in Teheran Fenton described as bizarre at best. Marg bar Carter ( Death to Carter"), a passerby says cheerfully, by way of greeting. Fen ton can think of no response except "hi." A waiter in a once elegant French restaurant, not yet habituated to strict Islamic temperance, would pour asoupcon of Pepsi-cola in a glass, then step back to allow the host to sample the vintage. Journalists, accustomed to paying under the counter for any sort of accommodations, were about the only paying guests left, and they were all in one hotel. "The new Hyatt House, which had just opened, was advertising 'free use of the facilities of the revolutionary country club, including a revolutionary 18-hole golf course' for anyone who'd stay there," Fenton reported.

He minimized the personal risks of the Teheran assignment. "It was a lot less nasty story to cover than most of that sort. The ayatollah told his followers that they were not to harm individual Americans, that their dispute was with the American government, so in fact there was relatively little molesting of foreigners."

"For a time," Fenton conceded, "there was some question about whether the press corps might be next to be taken hostage. And there was always the feeling that, if Khomeini could turn it off, he could turn it on and the situation could change in a matter of hours. As always on a story like this, you think of the individual position you would take." Fenton's closest brush in Teheran came one evening in front of the embassy. "An unruly crowd tried to lay hands on me, and one of them asked accusingly, 'CIA?' 'No, CBS.' I laughed. He laughed. And that broke the tension long enough for me to make a quick exit." Years ago, he said, he learned two principles for survival in such circumstances: "Never get between the police and the demonstrators. Always keep your eye out for an alley or some place you can sprint into."

Fenton is no stranger to hazardous assignments. He was covering the 1967 Six-Day War for the Baltimore Sun when he was first jailed, then evicted from Egypt. "It was one of the most remarkable stories I've ever seen, and I couldn't file a word." He was in Bangladesh with CBS when Indian troops first arrived in Dacca, and bunches of teen-age kids with submachine guns were still terrorizing the country.

His "wheels-up philosophy" - "you're never sure you're taking off until the wheels are up, and you never know what's going to happen until it happens" - makes him skeptical of predictions, but Fenton's guess all along has been that the hostage crisis would end peacefully. "Khomeini painted himself into a corner, but Bani Sadr and Ghotbzadeh and most, if not all, of the revolutionary council were looking for a way out."

The ayatollah, however, "has as broad support as any leader in the world," Fenton is convinced. "That is not to say that there are not a great many educated, middle-class Iranians who strongly dislike the obvious dictatorship he has created. But 60 per cent of the population is illiterate, and they live like Khomeini. Like them, he sits on a tattered rug and drinks tea."

While he waited for the new visa that was not to come, Fenton was working on a story about the Vatican crackdown on liberal Dutch theologians. "It seems to have been a religious year," he said wryly, "with a lot of the Pope as well as the ayatollah." Then Afghanistan broke, and he was off to Kabul in time to be placed under virtual house arrest and then expelled with the rest of the American press corps.

"This remote mountain republic, gently covered with snow, seems to be an island of peace and sanity," Fenton said in a midJanuary broadcast. "It's the rest of the world that has gone mad: warships heading for the Indian Ocean, rhetoric from Washington and Moscow that stirs uneasy memories of 30 years ago. . . . But here, in the peace of a snowfall, in this beautiful, primitive land centuries away from the world most of us know, it takes a great mental effort to imagine that Afghanistan could be the spark to set off a terrible war."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

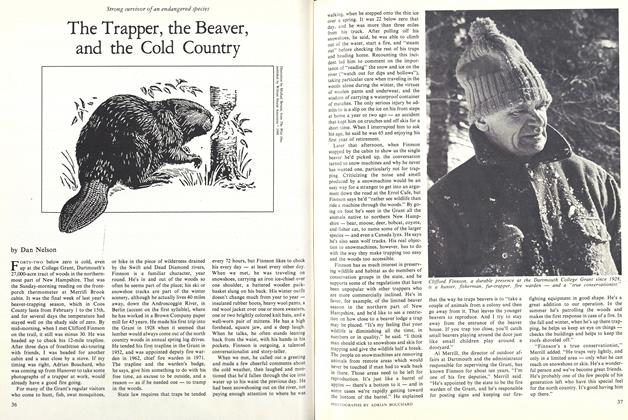

FeatureThe Trapper, the Beaver, and the Cold Country

March 1980 By Dan Nelson -

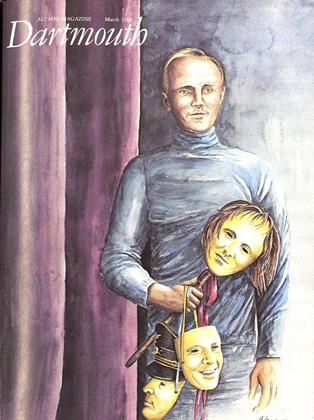

Cover Story

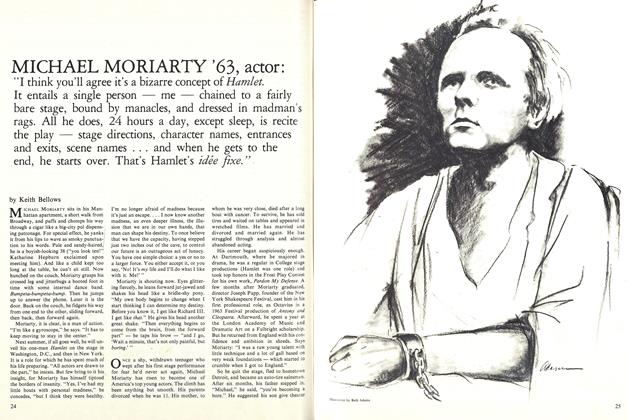

Cover StoryMICHAEL MORIARTY ’63, ACTOR

March 1980 By Keith Bellows -

Feature

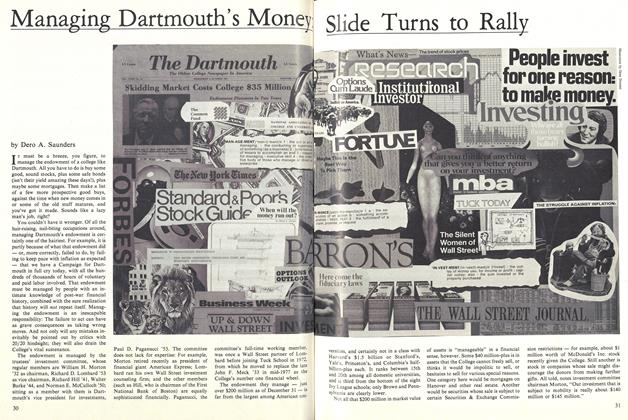

FeatureManaging Dartmouth’s Money Slide Turns to Rally

March 1980 By Dero A. Saunders -

Article

ArticleTracker of the Right Stuff

March 1980 By M.B.R. -

Class Notes

Class Notes1913

March 1980 By CARL C. FORSAITH -

Class Notes

Class Notes1978

March 1980 By JEFF IMMELT

M.B.R.

-

Article

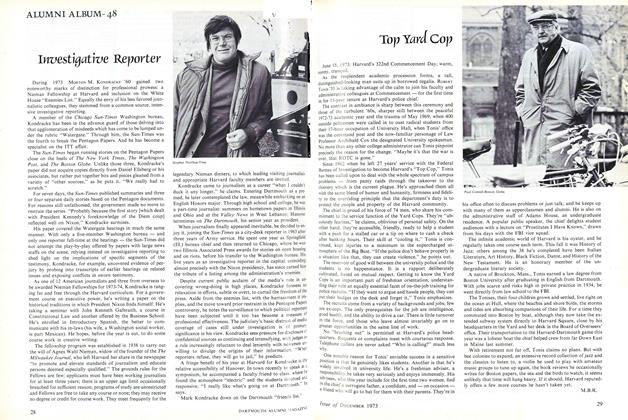

ArticleTop Yard Cop

December 1973 By M.B.R. -

Article

ArticleThe obscure little pin-prick circled above recently sent out x-rays more intense than any before recorded. But what is this "unusual thing" in the sky?

October 1975 By M.B.R. -

Article

ArticleDistrict Attorney

December 1976 By M.B.R. -

Article

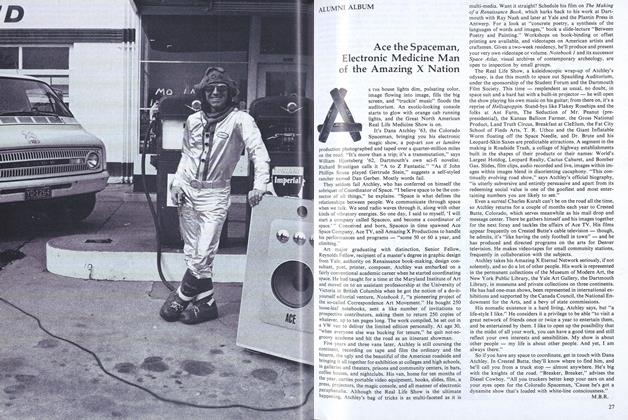

ArticleAce the Spaceman, Electronic Medicine Man of the Amazing X Nation

April 1977 By M.B.R. -

Article

ArticleKeeper of the College Attic

MAY 1978 By M.B.R. -

Article

ArticleMan of the Cloth

November 1978 By M.B.R.