Ted Unkles '80, a student in Professor Noel Perrin's environmental writing class, sent us the following report on conditions at the Lebanon dump, Hanover's plans for its trash, and what that all might mean for the College:

Ho.w to dispose of trash is becoming a major issue in New England. As the regional landfill in West Lebanon fills up, the waste disposal problem in the local Upper Valley area is getting worse every day. Soon, many towns, including Hanover, will have no place to dump their trash. That means that Dartmouth, which produces a quarter of Hanover's trash, is also affected. The landfill may have between four and ten years left, depending on, among other things, whether a decision is made simply to fill up the area to a level surface, or to create another New Hampshire hill this one of garbage, not granite. But the landfill will not last long, and towns that use it must start planning for the day when it closes.

The most likely solution that Hanover is considering is a two-part operation: a large-scale recycling program and an incinerating plant that would produce steam as a useful by-product.

Last November, Hanover appointed a committee, chaired by assistant professor of sociology David K. Miller and including myself, a student, as one of the seven members, to study recycling and make recommendations to the selectmen this year. We were charged specifically with finding ideas to increase publicity for Hanover's present recycling center, recommending a new site for an expanded center, and making a list of local purchasers of recyclable materials.

There is already a small recycling program in some dormitories and fraternities at Dartmouth. Organized and run by the Environmental Studies Division of the Outing Club, the program relies entirely on volunteer student labor, and so is rather limited. Still, they collect about 1,300 bottles from the dorms each week.

Furthermore, a rather informal recycling program has been in operation in Hanover for several years, run by the town's Public Works Department. Noel Vincent, a trucker and trash collector based in White River Junction, picks up the recycled material. Vincent has kept recycling alive in the Upper Valley through good times and bad, although he has often lost money collecting and transporting recycled goods. Recently, Vincent applied for a federally backed loan to allow him to expand his recycling operations. He wants to construct a 60-by-100-foot building to house a magnetic separator (for separating steel cans from aluminum cans), a glass crusher, paper and cardboard balers, and plenty of room for newspaper storage.

From the Town of Hanover's point of view, Vincent's plans to expand could not be timed better. James Campion, chairman of the Hanover selectmen, sees recycling and an energy-recovery system as Hanover's only long-term option. "I think we've got to recycle all that we can, and burn the rest. And as long as we're going to burn it, it's silly not to produce steam or electricity."

Back in 1978, when studies first began, Claremont, New Hampshire, appeared to be the best site for a regional energy recovery system. Campion, however, feels that Claremont no longer looks like the best alternative. "I think it would be better located right here in Hanover. The College could buy the steam."

Indeed it could. Dartmouth uses steam to heat almost every building on campus. The steam is produced in the heating plant and then piped around campus in one major loop with several smaller spurs serving buildings far from the center of campus. Richard Plummer '54, director of Buildings and Grounds, said, "We surely could use more steam. Our equipment is old here, and it breaks down a lot. On cold days we put out about 100,000 pounds of steam per hour, and even on warm days during the summer we produce 20,000 or 25,000 pounds. I would guess the town system would produce about 10,000 or 15,000 pounds per hour." (A pound of steam is the amount of steam that one pound of water yields when boiled.)

Such an arrangement would have its share of problems, though. "Where they would locate the steam plant, I don't know," Plummer said. "For economic reasons it would have to be close to our main loop or one of the spurs. It would be extremely costly further away from one of our steam mains, but there are very few potential locations near by."

What would be the long-term implications of such a system? If the project is developed, the town would probably adopt what is called mandatory source separation, in which residents separate different colors of glass, paper, cans, and nonrecyclable waste, which is then burned. "But this is a long time away from right now," Campion noted.

By the mid 1980s, residents of Hanover may be separating their trash from their recyclable material. Noel Vincent probably will have greatly expanded recycling facilities in White River Junction. And Dartmouth students may be getting some of their heat from the trash they threw out just the day before.

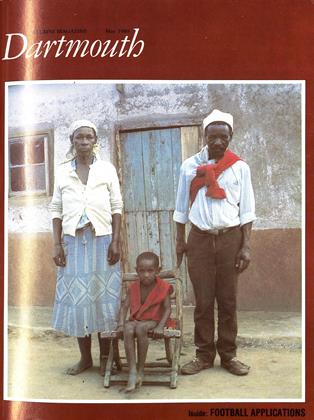

As part of a term-long celebration called "African Spring," the Dartmouth Playersproduced Edufa, a retelling of the Greek myth of Alcestis in an African tribalsetting. The play, written by Efua Sutherland of Ghana, was directed by DramaProfessor Errol Hill. Hopkins Center also featured African art, music, and dance.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

Cover StoryIn Two Worlds

May 1980 By Dan Nelson -

Feature

FeatureIn Another Country

May 1980 By Beth Ann Baron -

Article

ArticleAlchemist in Miniature

May 1980 By Michael Colacchio '80 -

Article

ArticleScientific Humanist

May 1980 By M.B.R -

Class Notes

Class Notes1978

May 1980 By JEFF IMMELT -

Article

ArticlePainting Medicos Have Both "Life" and "Work"

May 1980 By D.C.G