William Butler Yeats once said that a person has to choose between "perfection of the life, or of the work." But there are a few rare individuals who are able to achieve considerable recognition in an avocation, while also reaching the pinnacle in their vocation.

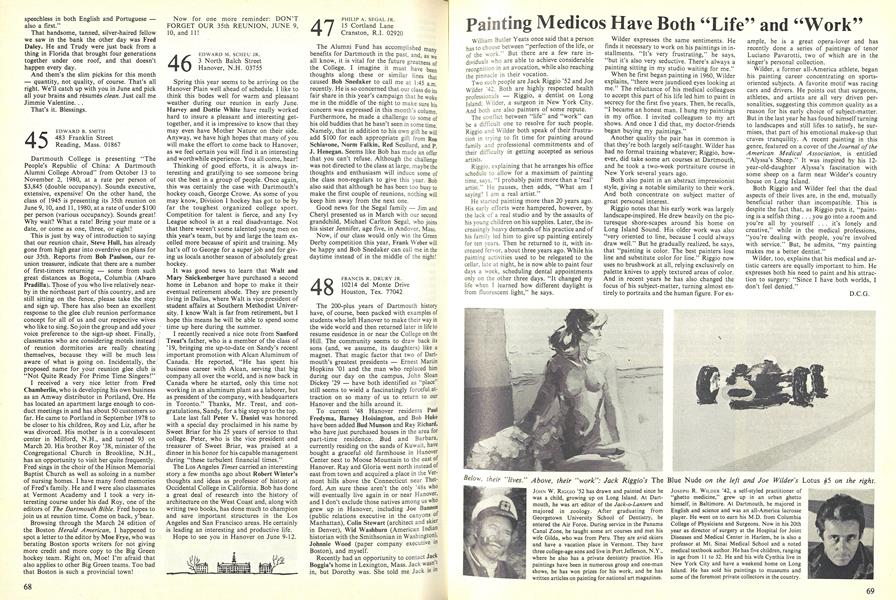

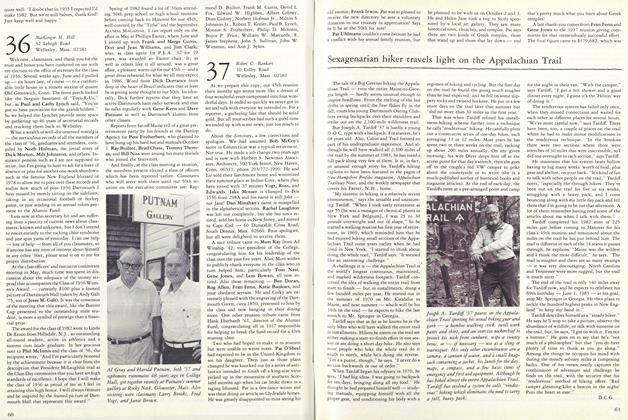

Two such people are Jack Riggio '52 and Joe Wilder '42. Both are highly respected health professionals Riggio, a dentist on Long Island; Wilder, a surgeon in New York City. And both are also painters of some repute.

The conflict between "life" and "work" can be a difficult one to resolve for such people. Riggio and Wilder both speak of their frustration in trying to fit time for painting around family and professional commitments and of their difficulty in getting accepted as serious artists.

Riggio, explaining that he arranges his office schedule to allow for a maximum of painting time, says, "I probably paint more than a 'real' artist." He pauses, then adds, "What am I saying? I am a real artist."

He started painting more than 20 years ago. His early efforts were hampered, however, by the lack of a real studio and by the assaults of his young children on his supplies. Later, the increasingly heavy demands of his practice and of his family led him to give up painting entirely for ten years. Then he returned to it, with increased fervor, about three years ago. While his painting activities used to be relegated to the cellar, late at night, he is now able to paint four days a week, scheduling dental appointments only on the other three days. "It changed my life when I learned how different daylight is from fluorescent light," he says.

Wilder expresses the same sentiments. He finds it necessary to work on his paintings in installments. "It's very frustrating," he says, but it's also very seductive. There's always a painting sitting in my studio waiting for me."

When he first began painting in 1960, Wilder explains, "there were jaundiced eyes looking at me." The reluctance of his medical colleagues to accept this part of his life led him to paint in secrecy for the first five years. Then, he recalls, "I became an honest man. I hung my paintings in my office. I invited colleagues to my art shows. And once I did that, my doctor-friends began buying my paintings."

Another quality the pair has in common is that they're both largely self-taught. Wilder has had no formal training whatever; Riggio, however, did take some art courses at Dartmouth, and he took a two-week portraiture course in New York several years ago. Both also paint in an abstract impressionist style, giving a notable similarity to their work. And both concentrate on subject matter of great personal interest.

Riggio notes that his early work was largely landscape-inspired. He drew heavily on the picturesque shore-scapes around his home on Long Island Sound. His older work was also "very oriented to line, because I could always draw well." But he gradually realized, he says, that "painting is color. The best painters lose line and substitute color for line." Riggio now uses no brush work at all, relying exclusively on palette knives to apply textured areas of color. And in recent years he has also changed the focus of his subject-matter, turning almost entirely to portraits and the human figure. For example, he is a great opera-lover and has recently done a series of paintings of tenor Luciano Pavarotti, two of which are in the singer's personal collection.

Wilder, a former all-America athlete, began his painting career concentrating on sportsoriented subjects. A favorite motif was racing cars and drivers. He points out that surgeons, athletes, and artists are all very driven personalities, suggesting this common quality as a reason for his early choice of subject-matter. But in the last year he has found himself turning to landscapes and still lifes to satisfy, he surmises, that part of his emotional make-up that craves tranquility. A recent painting in this genre, featured on a cover of the Journal of theAmerican Medical Association, is entitled "Alyssa's Sheep." It was inspired by his 12year-old-daughter Alyssa's fascination with some sheep on a farm near Wilder's country house on Long Island.

Both Riggio and Wilder feel that the dual aspects of their lives are, in the end, mutually beneficial rather than incompatible. This is despite the fact that, as Riggio puts it, "painting is a selfish thing . . . you go into a room and you're all by yourself . . . it's lonely and creative," while in the medical professions, "you're dealing with people, you're involved with service." But, he admits, "my painting makes me a better dentist."

Wilder, too, explains that his medical and artistic careers are equally important to him. He expresses both his need to paint and his attraction to surgery: "Since I have both worlds, I don't feel denied."

Below, their "lives." Above, their "work": Jack Riggio's The Blue Nude on the left and Joe Wilder's Lotus #5 on the right

JOHN W. RIGGIO '52 has drawn and painted since he was a child, growing up on Long Island. At Dartmouth, he was art editor of the Jack-o-Lantern and majored in zoology. After graduating from Georgetown University School of Dentistry, he entered the Air Force. During service in the Panama Canal Zone, he taught some art courses and met his wife Gilda, who was from Peru. They are avid skiers and have a vacation place in Vermont. They have three college-age sons and live in Port Jefferson, N.Y., where he also has a private dentistry practice. His paintings have been in numerous group and one-man shows, he has won prizes for his work, and he has written articles on painting for national art magazines.

JOSEPH R. WILDER '42, a self-styled practitioner of "ghetto medicine," grew up in an urban ghetto himself, in Baltimore. At Dartmouth, he majored in English and science and was an all-America lacrosse player. He went on to earn his M.D. from Columbia College of Physicians and Surgeons. Now in his 20th year as director of surgery at the Hospital for Joint Diseases and Medical Center in Harlem, he is also a professor at Mt. Sinai Medical School and a noted medical textbook author. He has five children, ranging in age from 11 to 32. He and his wife Cynthia live in New York City and have a weekend home on Long Island. He has sold his paintings to museums and some of the foremost private collectors in the country.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

Cover StoryIn Two Worlds

May 1980 By Dan Nelson -

Feature

FeatureIn Another Country

May 1980 By Beth Ann Baron -

Article

ArticleAlchemist in Miniature

May 1980 By Michael Colacchio '80 -

Article

ArticleScientific Humanist

May 1980 By M.B.R -

Class Notes

Class Notes1978

May 1980 By JEFF IMMELT -

Article

ArticleVox

May 1980 By Norman R. Carpenter '53

Article

-

Article

ArticleSECRETARIES' MEETING

-

Article

Article$1,000,000 GIFT PROVIDES FOR NEW LIBRARY

June, 1926 -

Article

ArticleCircling the Green

JAN./FEB. 1979 -

Article

ArticleMovie Classics Shown Daily As Experiment in Education

November 1960 By DAVID STEWART HULL '60 -

Article

ArticleDartmouth in Peru

JANUARY 1963 By EDWARD E. PARSONS 3RD '53 -

Article

ArticleMilton Sims Kramer

October 1954 By PETER F. GEITHNER '54