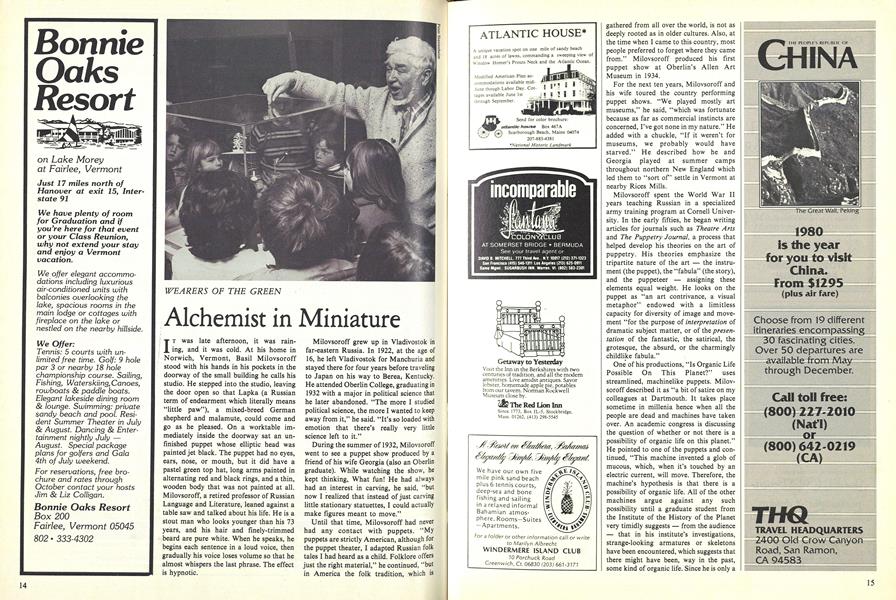

IT was late afternoon, it was raining, and it was cold. At his home in Norwich, Vermont, Basil Milovsoroff stood with his hands in his pockets in the doorway of the small building he calls his studio. He stepped into the studio, leaving the door open so that Lapka (a Russian term of endearment which literally means "little paw"), a mixed-breed German shepherd and malamute, could come and go as he pleased. On a worktable immediately inside the doorway sat an unfinished puppet whose elliptic head was painted jet black. The puppet had no eyes, ears, nose, or mouth, but it did have a pastel green top hat, long arms painted in alternating red and black rings, and a thin, wooden body that was not painted at all. Milovsoroff, a retired professor of Russian Language and Literature, leaned against a table saw and talked about his life. He is a stout man who looks younger than his 73 years, and his hair and finely-trimmed beard are pure white. When he speaks, he begins each sentence in a loud voice, then gradually his voice loses volume so that he almost whispers the last phrase. The effect is hypnotic.

Milovsoroff grew up in Vladivostok in far-eastern Russia. In 1922, at the age of 16, he left Vladivostok for Manchuria and stayed there for four years before traveling to Japan on his way to Berea, Kentucky. He attended Oberlin College, graduating in 1932 with a major in political science that he later abandoned. "The more I studied political science, the more I wanted to keep away from it," he said. "It's so loaded with emotion that there's really very little science left to it."

During the summer of 1932, Milovsoroff went to see a puppet show produced by a friend of his wife Georgia (also an Oberlin graduate). While watching the show, he kept thinking, What fun! He had always had an interest in carving, he said, "but now I realized that instead of just carving little stationary statuettes, I could actually make figures meant to move."

Until that time, Milovsoroff had never had any contact with puppets. "My puppets are strictly American, although for the puppet theater, I adapted Russian folk tales I had heard as a child. Folklore offers just the right material," he continued, "but in America the folk tradition, which is gathered from all over the world, is not as deeply rooted as in older cultures. Also, at the time when I came to this country, most people preferred to forget where they came from." Milovsoroff produced his first puppet show at Oberlin's Allen Art Museum in 1934.

For the next ten years, Milovsoroff and his wife toured the country performing puppet shows. "We played mostly art museums," he said, "which was fortunate because as far as commercial instincts are concerned, I've got none in my nature." He added with a chuckle, "If it weren't for museums, we probably would have starved." He described how he and Georgia played at summer camps throughout northern New England which led them to "sort of' settle in Vermont at nearby Rices Mills.

Milovsoroff spent the World War II years teaching Russian in a specialized army training program at Cornell University. In the early fifties, he began writing articles for journals such as Theatre Arts and The Puppetry Journal, a process that helped develop his theories on the art of puppetry. His theories emphasize the tripartite nature of the art the instrument (the puppet), the "fabula" (the story), and the puppeteer assigning these elements equal weight. He looks on the puppet as "an art contrivance, a visual metaphor" endowed with a limitless capacity for diversity of image and movement "for the purpose of interpretation of dramatic subject matter, or of the presentation of the fantastic, the satirical, the grotesque, the absurd, or the charmingly childlike fabula."

One of his productions, "Is Organic Life Possible On This Planet?" uses streamlined, machinelike puppets. Milovsoroff described it as "a bit of satire on my colleagues at Dartmouth. It takes place sometime in millenia hence when all the people are dead and machines have taken over. An academic congress is discussing the question of whether or not there is a possibility of organic life on this planet." He pointed to one of the puppets and continued, "This machine invented a glob of mucous, which, when it's touched by an electric current, will move. Therefore, the machine's hypothesis is that there is a possibility of organic life. All of the other machines argue against any such possibility until a graduate student from the Institute of the History of the Planet very timidly suggests from the audience that in his institute's investigations, strange-looking armatures or skeletons have been encountered, which suggests that there might have been, way in the past, some kind of organic life. Since he is only a candidate for a doctorate, all the other machines ignore him, of course, and well, if you've ever been to any faculty meetings, sometimes they're just as absurd."

Milovsoroff has always had an interest in filming puppet productions. He produced two educational films about safety in 1956-57 - Muzzleshy, a gunsafety film starring crows, and Poison inthe Home, which features ants. He said in reference to Muzzleshy that "gun-safety films had been done before with people, but killing is so commonplace that people ignore appeals from one another. However, when you get a bunch of stupid crows to do the same thing, there's some sense of humor in it and the message sticks." He dislikes the trend toward realism in puppet productions. "The stop-motion techniques are clever, but they make the figures too human, or too animal-like then they just aren't puppets anymore."

Shortly after making his two films, Milovsoroff accepted Dartmouth's invitation to join the Russian Department. In 1960, he became director of the National Defense Russian Language Institute, and three years later, after a year at Oxford, he was asked to reorganize the Dartmouth Russian Department into the present Department of Russian Language and Literature, which he chaired until 1967. He retired in 1972 and became free again to devote himself full-time to his puppets. He has no regrets about the time spent away from puppetry in the world of academia. "I don't like to work, but creative endeavors are not work. During my tenure at the College, at least most of the time, I felt my work was creative interesting things were happening. When they happened, I just didn't think of academics in terms of work. Oh, once in a while I grew tired, but what really aggravated me was that time runs too fast before you know it, you haven't accomplished all you set out to do . . . and then it's too late."

He walked behind a sawdust-covered polyethylene sheet into a tiny wing of his studio where he stores puppets, spotlights the sounding board from a piano, and lots of old books he has purchased here and there at book fairs. Many of Milovsoroff's puppets are not creations that one would automatically associate with Kukla, Fran and Ollie, or the Muppets. Some of them have been crafted from pieces of tree trunks, steel rods (the kind used in steel- reinforced concrete), telephone wire, and springs from old bicycle seats. He pointed to a group of these puppets, which measured about 18 inches in length and had outlines resembling fish, and said, "These are underwater things, and sup- posedly their bodies are translucent so that you're seeing their guts." He moved a wire attached to a spring on the midsection of one of the underwater things. "They glide very slowly," he said. "Sometimes they dip a little like this. The attempt is to invent motion underwater."

Milovsoroff is interested in all kinds of puppets hand puppets, marionettes or string puppets, rod puppets, and his own unique inventions. His earliest hand puppets had painstakingly-carved features, but he learned that "they must be rough because then they show much better on the stage. If they're too well-polished, they somehow don't have the same character."

Glancing around the small studio, he remarked, "What I need is a big barn where I could actually try out all my contraptions. Every time I go to the Center Theater at Hopkins Center and look at that cyclorama, I just drool! Think what you could do with that expanse using light and shadow." He finished with the comment, "Theater should be experimental at all times because, like anything else, once it becomes static, it's dead."

Milovsoroff brought up the subject of puppet theater in Eastern Europe where the governments support playhouses that employ over 200 people. He said that the Eastern Europeans insist on adult, professional artists, and they materially support puppet theater produced specifically for adults. "In order to make a living at it, for years Americans have had to produce puppet theater for mothers to entice them to bring their children to see the show. The puppetry in this country has depended on children's repertory for its existence, and adults will not take to it simply because once the frame has been set for this type of theater, it seems not to change."

He moved around behind an opaque screen and set to spinning an elaborate puppet that resembled a mobile. Shining his spotlights through colored filters, he projected colorful images of the puppet on the screen. "There you see what one can do with motion, color, and light," he commented, 'Now, listen." He picked up a rubber mallet and started a slow tapping, then a soft banging, on the strings of the piano, creating a curious, extraterrestrial tune to accompany the image on the screen. "It's the unusual that touches the imagination," he mused. 'l'm aiming to reach more people with my art, to arouse the curiosity of more sophisticated people."

Milovsoroff's puppets will be exhibited this coming June at the International Puppet Festival in Washington, D.C. (the first time the American government, through the Council for the Arts, he claimed, will have done anything as sub- stantial to support puppet theater). Milovsoroff's puppets have been displayed several times in the Rotunda of Hopkins Center. "If I was in the vicinity," he related, "I used to keep an eye out to see how my colleagues on the faculty reacted to the exhibits. If one would stop to take a look, I'd say to myself, 'My God, he's human! He then added with a loud laugh, 'But of the ones who walked by and paid no attention at all I would think, there's no hope for them!"

Milovsoroff s puppets: talking machines,forest idylls, and echoes of the Far East.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

Cover StoryIn Two Worlds

May 1980 By Dan Nelson -

Feature

FeatureIn Another Country

May 1980 By Beth Ann Baron -

Article

ArticleScientific Humanist

May 1980 By M.B.R -

Class Notes

Class Notes1978

May 1980 By JEFF IMMELT -

Article

ArticlePainting Medicos Have Both "Life" and "Work"

May 1980 By D.C.G -

Article

ArticleVox

May 1980 By Norman R. Carpenter '53

Michael Colacchio '80

-

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

JAN./FEB. 1980 By Beth Ann Baron '80, Michael Colacchio '80 -

Article

ArticleThe Bard's American Friend

September 1979 By Michael Colacchio '80 -

Article

ArticleZombie of the 1902 Room

October 1979 By MICHAEL COLACCHIO '80 -

Article

ArticleThe Five-Year Plan

December 1979 By MICHAEL COLACCHIO '80 -

Article

ArticleThe Great Society

April 1980 By Michael Colacchio '80 -

Books

BooksExperiential Education

OCTOBER 1981 By Michael Colacchio '80

Article

-

Article

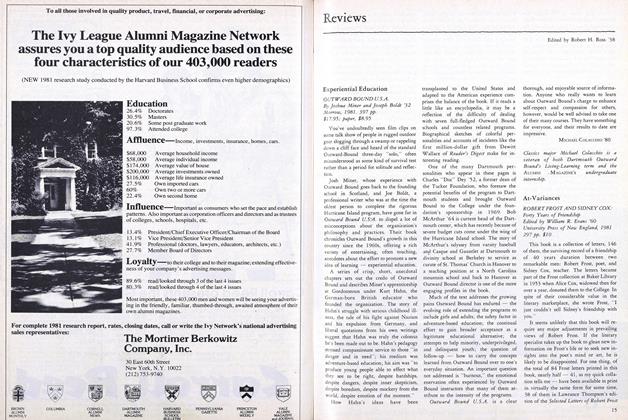

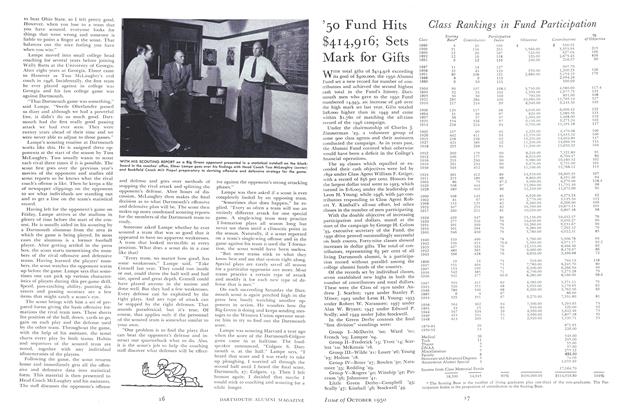

Article'50 Fund Hits $414,916; Sets Mark for Gifts

October 1950 -

Article

ArticleIndispensable Man

June 1953 -

Article

ArticleQueen Contest Dropped

FEBRUARY 1973 -

Article

ArticleMasthead

Jul/Aug 2004 -

Article

ArticleSome Misapprehensions in Regard to the Selective Process

February, 1931 By Charles R. Lingley -

Article

ArticleHouse Calls for the Twenty-First Century

NOVEMBER 1993 By Charles Wheelan ’88