The seeking the option of the snake

Gregory Rabassa won a National BookAward for his first translation, the novel Hopscotch by Julio Cortazar. Since hisdebut at the summit, Rabassa seems tohave gone nowhere but up, making 22more books three others are in embryoof the best of Latin-American authorsfaithfully accessible to readers of theEnglish-speaking world. He has beencalled quite simply "one of the besttranslators who ever drew breath" and "avery good writer" in his own right. Citinghim for the 1977 translation prize forGabriel Garcia Márquez' The Autumn of the Patriarch, his peers in P.E.N., the international association of writers, declaredthat "Gregory Rabassa has once againtriumphed over the intricacies of LatinAmerican baroque by his dedicated secret

SOMETIMES we feel constrained and narrowed in by what has been given to be around us, what Latin calls circumstance and what cliche modifies as particular or peculiar. Often people who sense this seek the option of the snake and sneak into another's skin: the actor, the mime, the spy, the just plain liar, and the translator. These are all modes of derivative creation, unlike that predicated by Goethe as being necessarily individual and lonesome. There are so many images, similes, and metaphors that we can use as we try to define translation. It can be of submitting to them. In Rabassa's version of Márquez on this new showing as onthe initial one [The Hundred Years of Solitude], and in so many other recreationsof a prose so alien, rhetorically, and so discrepant, individually, from our nativestrain, we are enabled to savor a languageat once recognizable as literature and asthe mind's own diction too delectable,convincing, rapid, charged."

Rabassa graduated from Dartmouth in1944 and is now professor of Romancelanguages and comparative literature atQueens College and the Graduate Centerof the City University of New York. Here,in an essay written for the ALUMNI MAGAZINE, he talks about the art and craftof translation, how it all started for him,and how he goes about it.

likened to the playing of a musical score arranged for an instrument other than the one in hand; indeed, a musician is said to "interpret" a piece, which is also the term used with reference to oral translation from one language to another.

Even more than critic or interpreter, however, the translator is or should be the ideal reader, the one who must have taken a course in slow reading (which Edwin Newman has said we are in more need of than the other kind). He or she must put this reading into words, albeit of a different language. Many of us remember how we had to do something like this in grammar school, writing a resume or precis for Mrs. Morrison or Mrs. Blodgett of something that had been given us to read. At other times we would have to explain something to a lesser creature, some three or four grades behind us, having recourse to the vocabulary of that level, else it would be for naught. So it is that most of us have been doing the essential chore of translation even before we met Miss Whitford and were called upon to construe Caesar. The passage from these seemingly inconsequential and ordinary experiences in the expression by us of what are the voices of others to a conscious effort to do translation on a formal basis happens to different people in so many different ways that I hesitate to suggest any common track other than the exodermic urges that I have suggested above.

My own story as to how I came to be doing what I am doing so much of the time is absolutely serendipitous and so uncomplicated as to be downright banal, and yet there might be a hint of certain predispositions whose clustering came about with the aid of particularly happy circumstances. Back in the early sixties I was going along merrily teaching Spanish, Portuguese, and humanities at Columbia when I was asked to join a group that would become the editorial board of a new journal Odyssey Review. We would be a quarterly, publishing in each issue a sampling of the best new writing from two European and two Latin-American countries. This meant that after making our selections we would have to see to the translations, lining up people to do them and checking the results. My chore was to scout out some good new authors (many of our "unknowns" have come to be quite well known) and to see that they were translated accurately. Then we would get together, and after I had vouched for the accuracy of the texts we would try to improve the style where we could, a collective act of artistry. Nowhere was I doing translations, although I must admit a few misgivings about some of the results submitted.

It came to pass quite soon that there were not enough translators to fill our needs, so I began to chippy around, doing an odd piece now and again. They turned out tolerably well, something that didn't really surprise me as most often it all went quite naturally. And so I began to do some translating, enjoying it, and doing it as fluidly as I had done in language classes in school. About the time that Odyssey was folding for lack of funds, Pantheon Books was looking for a translator for Julio Cortazar's second and definitive novel, Hopscotch. My name was suggested, and I met with Sara Blackburn, editor of the book, and we agreed on some samples. She liked them, Julio liked them, and that was the beginning. Both of them had been leery about what I would do with the pages because they had had experience with previous translators whose main qualification seemed to have been the teaching of the language and its literature. Sara had even conceived of a composite character who contained all the characteristics and whom she had dubbed Professor Horrendo (if he taught French he would be Horrendeaux).

What neither of them knew was that in the hectic forties, when care was thrown to the hill wind in our veins, along with a raffish group of jazz people in residence, I would hitchhike of a weekend from Hanover to 52nd Street and try to find Billie Holiday at Kelly's Stables, The Famous Door, or such, and listen to her at the bar, nursing what was then a quite expensive quarter beer. Cortazar has followed jazz from his earliest days and has even been known to woodshed on the trumpet. Then, when he came to find out that after the war, dividing time between doctoral seminars at Columbia and The Open Door in the Village, hanging out with tenor saxman Brew Moore in my pad on Morton Street, I got to know Charlie "Bird" Parker, the pact was sealed. Jazz has since become one of our strongest bonds, and whenever Julio comes visiting out to walk the dunes on the east end of Long Island, we trot out the good old 78s and listen to the likes of James Rushing or Bud Powell in orbit.

So I translated Hopscotch and it so happened that it won the first National Book Award offered for a translated work. This strange concatenation made me ponder the many questions asked me about approach and techniques with a certain puzzlement and reluctance to tell the truth about it all. In a very Cortazarian way, as things did not follow the accepted standard path and could not be described under such norms, life imitated art. I finally had to admit partly out of pure deviltry, but partly out of the hope that the circumstance might explain what translation is all about that I had not read the novel first, that I had read it as I translated it. I have thought about this since and I cannot find much difference in the matter of reading a book before translating it, or not. This bears out a contention I have had of what translation is in one respect: the closest possible reading one can give a text. This has to be so, because in this case we not only must understand the text, we must reproduce it, rewrite it. The important thing, then, has been the close reading, not the panorama. Perhaps only as we translate do we read every article, definite or indefinite, every jot and tittle.

Learning to read is really the obverse of learning to write. Once these two things have been learned, it is hoped that one will learn to speak, which, in turn, will enhance the ability to read and write: the pencil to the translator is what the voice is to the actor. As a writer, a translator must hear everything he writes. This will go a long way toward telling him if he is right or wrong. I have noticed that for many years I must have been reading orally, almost doing the duffer dodge of moving my lips. We used to make mean jokes about people who moved their lips when they read, particularly if they were eminences deemed semi-cretin. A while back I discovered that we do indeed hear what we read, just one step from moving our lips. I translated the Brazilian novel Avalovara, by Osman Lins. In this book the protagonist consorts with three different women. The first two offer no orthographical difficulties, at least; the third one, however, is not named. Lins has chosen to represent her by a symbol, based on all manner of arcane reference. When I came to this in my reading (I did read this book before translating it) I found it impossible to get by this rune, almost gagging on it. In order to complete my reading and to get on with the translation, I resorted to calling her "O."

One wonders what skills are needed to make an adequate translation (I feel that this is the highest we can praise a translation Nabokov gives even less ground and would tolerate only interlinear ponies). It is hard and most likely inaccurate to use oneself as the subject (cf. the uncertainty principle), even dangerous (cf. Dr. Jekyll), yet I can best describe how I work at the craft by considering the various facets of my formation.

I was not a stranger to foreign languages as my father was Cuban, nor was English foreign to me as my mother's family is a fifth- or sixth-generation line of New York WASPs (if Macfarlands can be allowed within the limitations of the AS; but my maternal grandmother was a Mosley from Manchester, and Uncle Tom did look so very much like Neville Chamberlain). Coming from this variegated heritage, between two tongues, two religions, two ways of life, if one is sensitive one begins to see the possibility of partaking of both while remaining a stranger on either side. This ambivalence was complicated by a move from the more tolerant native New York heath to the physical and spiritual austerities caused by the collapse of sugar futures on the commodities market as the Old Man turned his amateur farm north of Hanover into the Villaclara Inn so as to make ends meet.

So my schooling was all had in Hanover, all the way through Dartmouth. In childhood days I also knew what it was to be split geographically: In those times Hanover was very much on the Boston side of the cultural divide, and we sometimes felt like outlanders from the other side of the mountain Luden's people in Smith Bros, country and other such seeming trivialities. Because of this dichotomy, however, once more I was able to move with relative ease between the two rather different cultures and attitudes, one familial, one public. After all these years and all these experiences, however, I feel that the strongest cultural roots are still in New England, with a touch in the voice and the inevitable Yankee bit of blasphemy rather than New York or Southern scatology and pornography.

All of this has contributed to the development of the qualities of mind that a translator must have. He must be aware, very deeply so, in his marrow, that people make different combinations of sounds and utterances in an attempt to describe the same thing; that in addition to and underlying these differences there is a cultural discrepancy due to which a certain object or attitude might be completely alien or distasteful to one culture and commonplace in another. Lastly, there is that necessity for seeing other possibilities, realizing that the same coin has a reverse as well as an obverse. This characteristic is especially found in the northern New Englander, being the keystone of his skepticism. This is eloquently seen in Al Foley's old Vermonter and more often than not is the basis of the humor in so many of his tales. I have used some of these stories to show my students in translation at the City University of New York Graduate School that we must always be prepared for ambiguity and second meanings in words and expressions (e.g., Sen. Ralph Flanders, R. Vt., to foreman of wartime machine-shop: "How many men have you got working here?" Foreman: " 'Bout haalf of 'em.").

My first experience with translation as such began in high school with the usual practice of the times of using translation as a tool in language study. In both Latin and French classes this sort of exercise took up a great deal of time. In later years newer teachers turned against it in horror, favoring what was sometimes called the "direct method," the way language is learned by children, parrots, and talking dogs. This banal method does indeed have us speaking more like an inhabitant of the douzieme arrondissement, but at a rather low level. What it does not convey with logical immediacy is the difference in structure and choice between two languages and, thereby, the cultural divergences between the two peoples. By forcing a sentence or a whole paragraph from one tongue into another, one will quickly catch the differences and learn how the logic of the new language works, collecting paradigms along the way. He will also learn much about his own language, what he can expect of it for expression and how far he can bend it within the bounds of its natural expression.

I have said that a translator must be a reader, the closest and most careful one possible. He must also be a writer, one of the inventive sort, who knows his tools well. He must always find substitute solutions if the ones thought likely at first blush prove fraudulent. I had done varied amounts of ungoverned reading, but it was not until I read Proust with Ramon Guthrie at Dartmouth that I found out how to do it in a proper way. That combination of book and master brought forth as many epiphanies as the bite of any piece of madeleine or the wobble of any flagstone. As some kind of evidence that I liked to see things from different angles, I began to collect languages at college beyond the normative French and Spanish: Portuguese with warm Joe Folger and Russian with mysterious Dimitri von Mohrenschildt. Until those days I had not gathered many of these skills and tendencies together. Things just seemed to be falling into place in preparation for the ultimate serendipity. As I was learning to read with Ramon Guthrie, so was I .learning to write with Stearns Morse. When that delightfully lively man guided his son Dick and me along with some other chums over the Presidential Range, little did I wot that some years later he would be guiding me still along the paths of expression. With him I learned that writing must be as thoughtfully pondered as reading; there must be an end to mental gush and blather.

The next turn that would have some strange influence on future work came with the war. There happened to be some kind of connection between Dartmouth and the O.S.S. and soon one of the old crew, Bob Lang, was back on campus recruiting a raffish crowd for an outfit that meant nothing to us but that would keep us out of the infantry; it seemed we had cryptic minds. We still got stuck with the worst part of the infantry, namely basic training (some of us did it at Camp Fannin, Texas, which was called a Branch Immaterial Replacement Training Center the ring of cannon fodder). Eventually I got to Washington and thence to North Africa and Italy. Much of what we did concerned codes and ciphers. These were quite primitive in many cases as compared to contemporary cryptography, so there was a danger that if the clear text of a message fell into enemy hands the whole system would be compromised and it was therefore necessary for messages to be paraphrased before they were circulated within the command no matter how tight the security. As I translated many a message from English into English I had no idea that once more I was getting training for what I would later spend so much time at.

After Hopscotch I was approached by publishers to do more translations and the chain of books began. Alfred Knopf had always published a great number of foreign novels, some of them the best, and of late had taken a special interest in Brazil. What had begun for me with one little language collector's course at Dartmouth with Joe Folger ended with a Ph.D. in Portuguese at Columbia and a dissertation on black characters in Brazilian fiction. So Knopf came to me for the translation of The Apple in the Dark by the Brazilian novelist Clarice Lispector. I was pleased to be able to work on something in Portuguese, and also I had met Clarice and was fascinated by this lovely person who looked like Marlene Dietrich, endowed with Thomas Mann's Kirghizenaugen, and wrote like Virginia Woolf.

From this experience I came to believe that a translator should really work from more than one language into English. Working in two different languages shows even more how thoughts and views differ. Spanish and Portuguese are deceptively similar to the untutored observer. A great deal of fanciful popular philosophy has come of this: the absurd notion that Portuguese has a French influence because of certain common sounds, perhaps because the father of Portugal's first king was a Burgundian count. It really sounds more like Spanish spoken by a Russian. A Spanish speaker can easily read a text in economics in Portuguese, but he cannot order a meal in a restaurant. I was therefore very happy for many reasons to do this Brazilian novel, hoping that it might make Americans realize that half the people in South America speak Portuguese.

At about this time I was approached by publisher Seymour Lawrence concerning a Guatemalan novelist he felt had been neglected. Of all the works left to be done by Miguel Angel Asturias, I proposed his wildly surrealistic novel Mulata, which I still consider his best piece, because it seemed so much in tune with what others were writing in Latin America. A few days after publication I got an early-morning phone call from Sam Lawrence informing me that Asturias had won the Nobel. They rushed off a new jacket, and there was the usual vindictive flurry from fans of other authors, but the book went largely unnoticed. At least it did get into paperback, which is where Latin American and other foreign books get their best sales in our generally sensationalist and chauvinistic marketplace. Thinking that the Nobel would arouse interest and that people should know something about the author's rather noble political stance, I undertook the translation of Asturias's so-called banana trilogy, where he lays out the awful truth about United Fruit. I soon had regrets and my efforts, always true to the text, coupled with the mostly accurate reviews, led me to state somewhere that the translator is not in the silk-purse business; he must try to reproduce what he has in front of him with all its warts and hairs like a page from the old-time version of TheNation. What Asturias had needed in these novels before a translator was the editorial hand of a Maxwell Perkins. The trilogy would make one excellent book.

It was around this time that I got an inquiry from Cass Canfield Jr. at Harper and Row, for whom I had done The GreenHouse, by Mario Vargas Llosa, as to what I was up to. I was rather tied up, I told him. He replied that he had bought the rights to a novel that had been causing a sensation in Latin America and elsewhere: One Hundred Years of Solitude, by Gabriel Garcia Marquez. It seems that Gabo, as we call him, had been advised by Julio Cortazar to get me for this one, even if he had to wait until my decks were cleared; he thought it that important. This was a book that I had read, and I agreed with everything that had been said about it. I started on it as soon as I could (doing two books in tandem is good for the variety it affords and enhances relief in both the recreational and sculptural sense of the word), and translating it was a delight; it is one of those works that almost translate themselves. The prose is so classical, so correct (in the good sense) that only a fool or incompetent could gum it up. Rather than stream-of-consciousness, one might call the technique of following a book like this stream-of-awareness, close but not quite the same, just as translation is itself. The novel is intensely local, even personal, with characters and events coming out of the author's own private ken, and yet it is most universal. This could be due to the language, the essence of what good Castilian prose should be, where just the right word in the right place brings the personal and the universal into the same exact focus.

As in the case of Cortazar, I consulted with Gabo when I needed to, which was nowhere so often. He would come to New York on occasion, but only when officially invited by some institution and then under great restrictions. He is still on the childish blacklist maintained by the State Department that makes us look more and more like Freedonia, although I doubt that Rufus T. Firefly would have countenanced such assininity in his presidency. Julio Cortazar, too, had been blacklisted, but a strangely condign solution based on jazz connections got him in. Yellow-Dog Democrat that I am, I seem to have known more people in Dr. Nixon's administration than any other (Clark MacGregor had lived upstairs in College Hall; I had bought a used car, no less, from former tenor man Leonard Garment). A quick note to Lennie, the wheels turned, and in came Julio. He has since been coming back with some regularity, and they have even let him see the Grand Canyon of the Colorado and the Orozco frescoes.

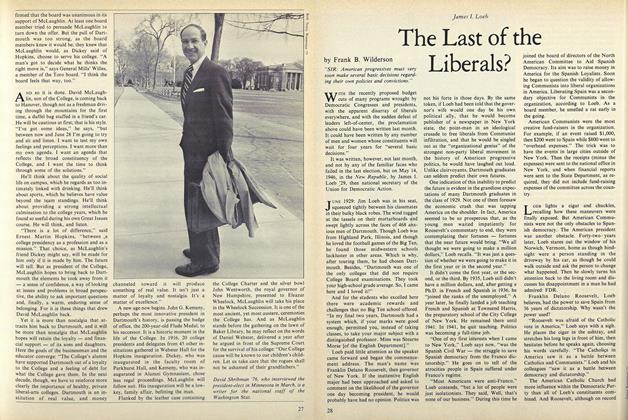

So when Gabo came we would talk about the translation and cabbages and kings, all of which is helpful as one gets into the other skin. There is an obvious need for mimicry in the craft of translation; one is a kind of actor playing the role of the original author, trying to interpret how he or she would have done things had English been the native language. Back came the skills I had developed in the Footlighters at Hanover High School, which I coupled with a certain knack for mimicry. When the translation was done and published, Garcia Marquez said in a Borgesian sort of way that he liked it better in English than in the Spanish version he had written. This, of course, was the ultimate in compliments, due as much to his graciousness as to his deviltry. Like Joyce, Garcia Marquez confounds his critics by accepting all interpretation of his work, extant and future, as writ. It is this combination that endears these writers to me, their ability to be so playful, to follow their nature, as at the same time, also following their nature, they go up against the vile and evil forces of greed and inadequacy that rule so many of their republics.

Along with the fun involved in doing most of these translations, there has also been the satisfaction of having contributed some good in two directions: giving American readers a chance to read some great new books they might otherwise have missed, and letting Latin-American and Iberian authors have an opportunity to enlarge their spheres. It is especially refreshing to see how an author like Demetrio Aguilera-Malta has come to receive the attention he has so long warranted as one of the first to express what Alejo Carpentier called the "marvelous real." Demetrio has a special place in our life as my wife Clementine wrote her dissertation on his work, showing that the epic is alive and well and hiding in the Latin-American novel. She has subsequently written two books on this fervent yet quiet man whom I first met by chance in Mexico many years back (he is now Ecuador's ambassador to that country). There is a wry footnote as to how my translation of his novel Seven Serpents andSeven Moons came to be published. I had been slowly working on it as a labor of love for Demetrio and mentioned that fact in an interview for The Wall Street Journal. There were immediate inquiries from publishers about the novel, and it was ultimately published by the University of Texas Press. So one of the founders of the Socialist Party in Ecuador owes his publication in English to that solid capitalist organ.

The translation of Latin-American literature that I have done has been spread out, therefore. I have helped bring recognition to some writers who had been neglected too long, I have kept the American reader abreast of some of the important writers in the great surge that has been called the Boom, and I have also had the opportunity to bring to the fore some writers of the newer generation who follow along and deserve the same recognition as their elders. Over these years I have seen Latin-American writing pass from a collection of strange, exotic cliches, fit only for the anthropologist, as Lionel Trilling once remarked in one of his more myopic moments, to a situation where it now often leads and influences. Last summer I was in Portugal gathering material under the auspices of the National Endowment for the Humanities for an anthology in translation of the works of the Luso-Brazilian missionary, statesman, preacher, and many other things, Padre Antônio Vieira, whose life encompassed almost the whole of the 17th century and who stands out so vividly to show that modern man finds his origins more with what we could call "baroque man" than with the vaunted renaissance man.

Now the art and craft of translation is enjoying a great wave of popularity and interest. Perhaps we are going through another Dryden age. Let us hope that we will not see the usual surcease of such noble intents. Colleges and universities are now studying the art in both critical and creative courses with rather good results. One of the great pleasures I derive from my own seminar at the C.U.N.Y. Graduate School is to see the works of students published. As yet, however, I have only been able to give them little bits of instinctive advice that would come under the description of editing. Unlike the teaching of a language, I cannot give them the rights and wrongs of what they are doing. My own accidental experience leads me to believe that the art of translation is the art of choice, as is life itself, and that success or failure is determined by the mysterious alembic each of us is in the distillation of all experience.

Gabriel Garcia Marquez (above) liked One Hundred Years of Solitude better inEnglish than his original Spanish. Rabassa(below, right) with jazz fan Julio Cortazar.

Gabriel Garcia Marquez (above) liked One Hundred Years of Solitude better inEnglish than his original Spanish. Rabassa(below, right) with jazz fan Julio Cortazar.

Others in the Rabassa circle: surrealist and Nobelist Miguel Angel Asturias(above) and Osman Lins (below), authorof Avalovara, creator of difficult runes.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

Features

-

Feature

FeatureNorth Country Doctor

NOVEMBER 1966 -

Cover Story

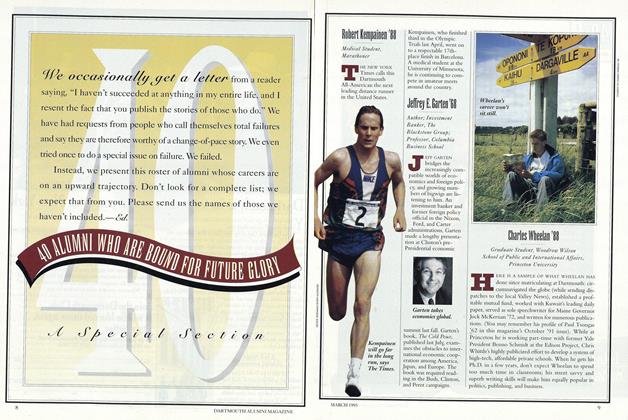

Cover StoryRobert Kempainen '88

March 1993 -

Feature

FeatureWhitewater Racing Gains New Status

OCTOBER 1969 By JAY EVANS '49 -

Feature

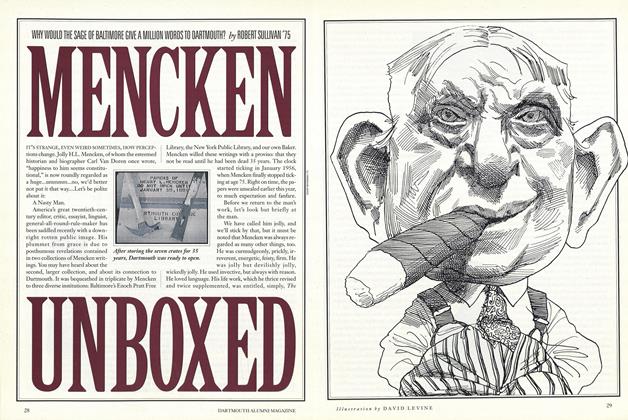

FeatureMENCKEN UNBOXED

OCTOBER 1991 By ROBERT SULLIVAN '75 -

Feature

FeatureMoriarty Ad Lib

Winter 1993 By Robert Sullivan ’75 -

Feature

FeatureWhy an Engineer Needs English Lit

May/June 2003 By SAMUEL C. FLORMAN ’46, TH’46