WHY WOULD THE SAGE OF BALTIMORE GIVE A MILLION WOODS TO DARTMOUTH?

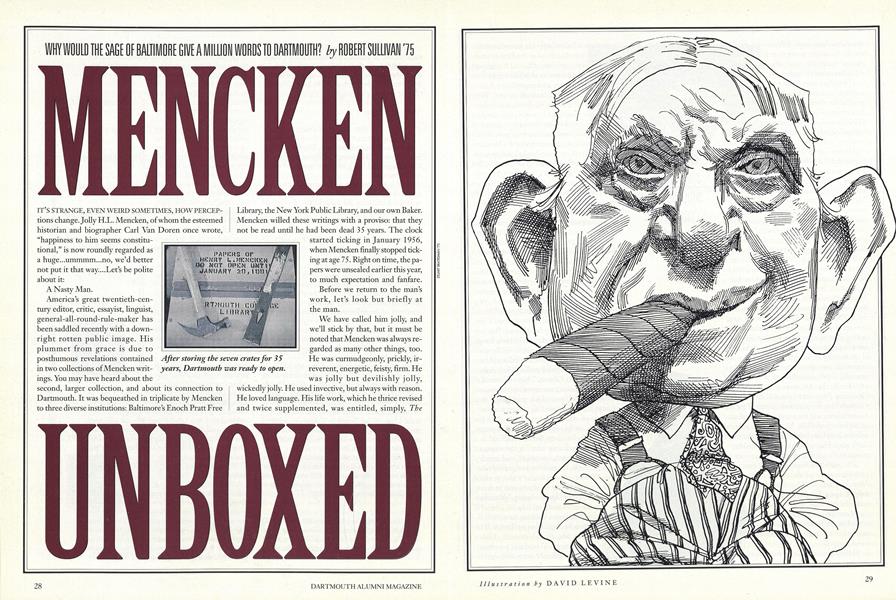

IT'S STRANGE, EVEN WEIRD SOMETIMES, HOW PERCEPTIOS change. Jolly H.L. Mencken, of whom the esteemed historian and biographer Carl Van Doren once wrote, "happiness to him seems constitutional," is now roundly regarded as a huge...ummmm...no, we'd better not put it that way....Let's be polite about it:

A Nasty Man.

America's great twentieth-century editor, critic, essayist, linguist, general-all-round-rule-maker has been saddled recently with a downright rotten public image. His plummet from grace is due to posthumous revelations contained in two collections of Mencken writings. You may have heard about the second, larger collection, and about its connection to Dartmouth. It was bequeathed in triplicate by Mencken to three diverse institutions: Baltimore's Enoch Pratt Free Library, the New York Public Library, and our own Baker. Mencken willed these writings with a proviso: that they not be read until he had been dead 35 years. The clock started ticking in January 1956, when Mencken finally stopped ticking at age 75. Right on time, the papers were unsealed earlier this year, to much expectation and fanfare.

Before we return to the man's work, let's look but briefly at the man.

We have called him jolly, and we'll stick by that, but it must be noted that Mencken was always regarded as many other things, too. He was curmudgeonly, prickly, irreverent, energetic, feisty, firm. He was jolly but devilishly jolly, wickedly jolly. He used invective, but always with reason. He loved language. His life work, which he thrice revised and twice supplemented, was entitled, simply, TheAmerican Language. Because he revered words, he wasn't wont to suffer fools who abused them. He went after these people, some have said savagely.

His heroes were Shaw and Nietzsche (he wrote a book about each). Of his contemporaries he championed progressives such as Anderson, Conrad, Dreiser, Lawrence, O'Neill, and it's interesting to note, in light of developments that we'll get to in a moment —James Joyce and Sinclair Lewis.

Henry Louis Mencken was born on September 12,1880, in Baltimore, a city he would come to represent as Damon Runyon symbolized Broadway, as Raymond Chandler embodied L.A. He discovered Mark Twain upon his father's bookshelf when he was not yet a teen, and he always maintained that this find was a pivotal event in his life. He wrote for his town's Herald beginning in 1899, and then for the rival Baltimore Sun beginning in 1906. He stayed with the Sun until 1948, but wore several other fedoras in the meantime. In 1908 he became drama critic of The Smart Set, a publication he co-edited with George Jean Nathan from 1914 until 1923. In 1924 he founded the famous humor and culture magazine The American Mercury, and was its editor until 1933. He was once arrested for selling copies of the Mercury that contained his outspoken views against censorship.

In the twenties and thirties Mencken was regarded as one of the nation's intellectual giants. But even some of his fans, who delighted in the barbs he aimed at America's "booboisie," wondered about Mencken's pro-German bias, his seeming contempt for the lowest classes, and the unfathomable intensity of his hatred of FDR. Mencken the political man has long been hard to figure precisely, and that's something to keep in mind when we return to the current contretemps.

Still, with the florid face, the expressive eyes, and the round cigar, Mencken was held by most to be jolly, if, again, fiendishly jolly. It was assumed that those who were stung by Mencken's sting probably deserved to be thusly pricked. The conventions he punctured deserved to be popped.

Mencken, certainly a genius, never attended college. He was educated in the hard-knocks school of deadline journalism. He was therefore affiliated firmly with no single institution to which he might have donated his library and papers.

Even so, the question arises: Why Dartmouth? Baltimore's Pratt makes absolute sense. Young H.L. was a card-carrying member of its Hollins Street branch before he was nine, and the library is now the financial and literary executor of the Mencken estate. The New York Public Library is, after all, The New York Public Library. But why Baker? What did Dartmouth do to deserve the large man's largesse? How did our controversy-prone college get dragged into yet another brouhaha, this one over the true feelings of a long-dead social critic?

Dartmouth was selected by benefactor Mencken for a couple of reasons. The larger factor, in all probability, had to do with the fine Mencken collection already assembled in Hanover by a Mencken disciple, Richard Mandel '26. Mencken felt warmly about people who recognized justly, he was sure his brilliance. Mandel respected Mencken's writing to the point of having purchased an annotated volume of Mencken's first book, Ventures Into Verse, "Being," according to its subhead, "Various Ballads, Ballades, Rondeaux, Triolets, Songs, Quatrains, Odes and Roundels, All Rescued from the Potters' Field of Old Files and here Given Decent Burial. Peace to Their Ashes. First (and Last) Edition." Any collection of Menckeniana so impressive that it contained Ventures Into Verse, which was issued in a printing of fewer than 100, was certainly deserving of added luster. Or so thought Mencken, as he was deciding his legacies.

The other reason Baker benefited is a shimmeringly lovely one: In the event of atomic holocaust, or other and' sundry Armageddons, Hanover was an unlikely target. "There is the risk that some or all of [the papers] may be destroyed in some future war or in a revolution," Mencken wrote in his diary on July 26, 1945. "If there is ever a raid on American libraries by radicals my papers will be among the first destroyed. I have sought to get 'round this possibility by sending duplicates to different libraries, but it may not work."

Well, H.L., it has worked so far.

That Mencken thought his work worth preserving even as the rest of the world smouldered is some small comment on the big man's big ego. Another, more whimsical illumination to be gleaned from a moment's reflection on this Baker Repository question is this: Just how bumpkinish are we? If they (who is they these days, anyway?) dropped the big one tomorrow, certainly Cambridge (perhaps both Cambridges?) would be candidate for ground zero. But isn't, say, Middlebury more out of the way than Hanover? Apparently when viewed from the Baltimore of the 19505, Dartmouth seemed synonymous with rusticity itself Hicksville, NH, no zip needed. Surely, Mencken seems to have felt, the Russkies wouldn't bother themselves with such a trifling li'l schoolhouse. His rationale is Daniel Webster inverted: It is, Sir, as I have said, a small college, and there are none that bother to hate it all that much.

Anyways, Mencken spun his wheel of for-tune and Dartmouth was one of the lucky institutions that were sent seven substantial boxes filled with Old Master scribblings, each box nailed shut. In a nice touch, Mencken made sure Dartmouth's copies were bound in green leather before beingdropped into the crates. When the shipment arrived in Hanover, well-muscled B&G guys lugged the boxes over to Baker and hefted them onto shelves in a secret room, the precise location of which remains undivulged even now by the College Librarian. There, in hiding, the boxes sat for the prescribed 3.5 decades, with little mind being paid to them.

Let's make that 3.4, because a couple of years ago people started giving those mysterious boxes a lot of attention.

This heightened interest was generated by the 1989 publication of the MenckenDiary. This private journal, according to its editor, Charles A. Fecher, proved that old cigar-chomping Mencken was racist and virulently anti-semitic. Adjectives preceding the word "Jew" in the Diary included "shrewd," "clever," "low-grade," and, rather cryptically, "young Harvard." Fecher's interpretation: "Let it be said at once, clearly and unequivocally: Mencken was an anti-semite."

Not everyone agreed. Mencken friends and even foes rushed to the silenced man's defense. They pointed out that, in the context of the times, Mencken's expressions weren't so very awful or even, ahem, politically incorrect. They argued that many others among the literati, not to mention nearly all the denizens of Bal'mer bars, spoke that way back then."I can remember that Mencken once said, 'I can't understand how any intelligent, civilized person could be anti-semitic,'" Andrew Spivak, former business manager of the Mercury and the "young Harvard Jew" in question, told The American Scholar. Of course, such rebuttal only served to fan the flames. The controversy created more than a modestly distingue New York Times sensation. It grew to be a positively People-magazine sensation. Mencken, long dead, was as alive as ever.

Suddenly, Mencken scholars were joined by a multitude of Mencken gawkers in being fascinated by the unopened boxes residing placidly in Baltimore, New York, and Hanover. What could be in there? More juicy stuff, I'll bet! This guy's better than Kitty Kelley! During the last year, the frenzy to feed on the contents grew and grew. It is to the College's everlasting credit that Geraldo (as in Geraldo!) wasn't summoned to New Hampshire to report on the Grand Opening, a la that breathless "Al Capone's Secret Vault!" TV special.

Early on the morning of January 29 all was ready at Baker. The ceremony was to take place in the dark, oiled-wood Treasure Room of the library's Special Collections wing. (Don't bother to recall it; you probably never studied there.) In a deft bit of staging, College Special Collections Librarian Philip N. Cronenwett had opened Daniel Webster's glass-cased, double-elephant folio first edition of Audubon's Birds of America to the oversized print of a Baltimore oriole.

Once the boxes and witnesses had assembled including President Freedman, who said he could scent "the delicious aroma of expectation" Cronenwett took a crowbar in one hand, a hammer in the other, and whaled away. "Never has there been a noise like that in the Treasure Room," Cronenwett said later, with only a modicum of contrition.

As a point of decidedly minor historical interest, Baker beat both the New York and Baltimore libraries in the race to unveil the latest Mencken. The NYPL is undergoing renovations, and had decided to sit on its closed crates until there was a suitable place to house the manuscripts. The Enoch Pratt Library had wanted to have its opening synchronous with Dartmouth's, but the librarian there hadn't brought the proper tools. The blue-ribbon ceremony in Baltimore was delayed while academicians scurried about, looking high and low for heavy snippers and a crowbar.

Meanwhile, Dartmouth's mass of Mencken seven volumes, nearly a million words was being descended upon by intellectually voracious little fellows in eyeglasses. (Well, there were beat guys from AP, UPI, and The Boston Globe there as well. Mencken, their soulmate, would have approved.) They pored over the pages, salivating all the while but trying not to drool on the priceless parchment.

And what did these serious-minded folks report to the world? This:

"All the while I knew Sinclair Lewis he was either a drunkard or a teetotaler, so my relations with him never became what could be called intimate, for I am ill at ease with any man who is either."

And this:

"Ulysses seemed to me to be deliberately mystifying and mainly puerile and I have never been able to get over a suspicion that Joyce concocted it as a vengeful hoax."

That commentary appeared not once but at least thrice in The Times, and played elsewhere just as frequently. Heaped atop the previous year's Jew-hater stuff, the Lewis quote in particular bolstered Mencken's burgeoning reputation as Mr. Nasty. This guy wasn't just a bigot (folks were now saying); he was a bitch!

We like to think such things about intellectuals and otherwise famous figures. It humanizes these outsized people. The British, for instance, think it's terrific that Shakespeare impregnated his wife when she was not yet his wife. We Americans love it that Richard Nixon prayed to paintings and asked God for counsel or was it the other way 'round? during his darkest, drinkingest days.

It's not nice of us to think this way, perhaps, but it's fun.

Still and all, I sat there in New York, reading The Times, and I grew confused. Once I had finished snickering over the Lewis quote, I thought: Wait a second here! Is that all there is? Mencken's was one of the fabulous minds of the century. There must be more in those manuscripts than this...this...this cattiness!

Unable to alter my vision of the great Mencken to that of a weaselly sleazebag sort of Truman Capote with a cigar I trekked to Hanover and headed for Baker. I ruminated as I traveled that this sortie was rather remarkable. Back in the seventies, I used to have trouble making it to the library from across the street in Hitchcock Hall. Now here I was taking a cab to LaGuardia and flying to Hanover in an airplane in order to hit the stacks and do some booking. Things change, as they say. I guess there's nothing as compellingly distracting as fris bee and beer pong in my life these days.

Phil Cronenwett proved to be a most helpful and accommodating man. He said he had already read all of the 4,000 or so pages, and explained exactly what they constituted. They were not mere jottings and musings, he said, nor were they diaries, as had been published in '89. They were a work, a magnum opus, a whole hunkish ouevre. Actually, they were two works: the three-volume MyLife as Author and Editor and the four-volume Thirty-Five Years of Newspaper Work. They were polished manuscripts, darned near ready for the printer. They made up "an indepth, personal view of the history of American literature and American journalism in the first half of the twentieth century," according to Cronenwett.

In the 1940s Mencken published three books of autobiography largely lyrical, even rhapsodical stuff, spiritually akin to Mark Twain's bouquets to his bygone Mississippi days. (By the way, the original manuscripts to those Mencken books Happy Days, Heathen Days, and Newspaper Days also are owned by the College.) The boxed material was in no way related to that previously printed prose. In the published autobiographies, Mencken observed himself as he traipsed easily through a funny and kindly world. But the boxed pages found Mencken appraising not himself so much as others, said Cronenwett, and not often with his saber sheathed. In 1945 Mencken promised that the boxes would contain "the plain truth, regardless of tender feelings," and he had, said Cronenwett, fulfilled that pledge in spades.

"Mencken has given very honest opinions of people here Lewis, Joyce, Pound, Eliot, and others," said Cronenwett. "Painfully honest. For instance, he felt Joyce was something of a kept man that Sylvia Beach and her Shakespeare & Company underwrote Joyce and allowed him to live a life of some lassitude. Now Mencken always expected someone to be able to crank it out on deadline, so obviously he was critical of such an arrangement."

Since a million words is a bit beyond my oh-let's-give-it-a-quick-read capacity, and since I'm not really up to all-nighters these days anyway, I wasn't dismayed when Cronenwett informed me that the Pratt Library, in its role as Mencken executor, had put the kibosh on further showings of the manuscripts to journalists and other such lowlifes. Cronenwett, an honorable man, refused to confirm the rumor that the Pratt was acting petulantly, and that it was angry with Dartmouth for stealing the thunder on opening day.

Cronenwett said he could show me a few pages in order to give me a feel for the manuscripts, and that he could talk about other parts he had read. He departed, and returned shortly from some secret place, carrying with him a box filled with typescript. I opened the box gingerly. I did not, I feel compelled to report, mark up the Mencken manuscripts with a felt-tip, nor did I bend over the pages to mark my place. Whether I've done such things to other Baker volumes in my dark past remains between me and the God of the Stacks.

I lifted the pages gently from the box one at a time and held them lightly so as not to smudge. The pages, which had been expertly typed by Mencken's longtime secretary Miss Lohrfink, were neat and, mostly, clean. Mencken had made some amendments in pencil and ink during his final edit.

Handling each sheet, with Mencken's markings come alive right there after 35 years of hibernation, was a stimulating if somewhat eerie experience. I smiled as I read the familiar, taut, lucid, vibrant prose. Even when Mencken wrote mean he wrote lean and lively.

Relying upon what I read, and upon what Cronenwett told me, I can report with confidence three things about the two volumes.

First: The writing's terrific. No major surprise here. But, still, this is serendipitous because the largest part of the manuscripts was written late in Mencken's life, after he had retired from magazines and even, at long last, from The Sun. It had been generally felt that he wrote less well when he was older. If that remains true, it is now less true than it was. Here's an excerpt: "It was the fashion in the Cocktail Age," Mencken wrote, "for married women of any pretensions to have followers, and Gracie soon acquired one in a man who alleged that his name was Tellesforo Casanova and that he was a Spanish Count." The facility with which Mencken conjures up a time and a situation has everything to do with gracefulness coupled with talent. Both Thirty-fiveYears 0f... and My Life as... make for wonderful reading.

Second: There is much more herein for the gossip-mongers. Just as a f' rinstance, the sentences that follow the Casanova introduction read thusly: "Nathan and I suspected that he was actually a Grand street Jew, and diligently spread a tale to that effect, but Gracie took him at his face value, and was vastly flattered by his attentions. Her flaunting of them caused a great deal of malicious snickering at Red, and he found that his inferiority complex was not enough to console him. One day he came to lunch with me at my apartment in the Algonquin, told me at great length the tale of Gracie's attentats against his husbandly honor, and burst into hysterical tears at the table."

Well! As Ronnie Reagan once observed, there you go again.

Let's forget for a moment that Senor Casanova is being characterized as a "Grand street Jew" an even more abstruse designation than "young Harvard" and let's try to forget that the estimable H.L. Mencken and G.J. Nathan are gleefully spreading malicious rumors about someone they've only just met, and let's ignore the obvious lack of discretion in detailing another person's crying jag, and let's also ignore that, if we were to continue with the quotation, we would find Red "white with rage" and Casanova sitting beside Gracie "stroking her bare arm...while she purred at him ecstatically" and then the two of them "taking frequent headers through the Seventh Commandment." Let's forget and ignore all that. Even so, we're still left with the fact that "Red" is Sinclair Lewis, an American Nobel Prizewinner for God's sake, and that "Gracie" is his then wife!

"Yes, well," said Cronenwett, who will defend Mencken to the grave and far beyond. "Yes, well, Lewis was a friend and Mencken hated Gracie for what he felt she was doing to Lewis dragging him down, ruining his work. So Mencken went after her.

"But, sure, there's a lot of A MoveableFeast about these manuscripts. I mean, AMoveable Feast tells us as much about Hemingway as it does Fitzgerald, doesn't it? And these pages tell us as much about Mencken as about his subjects. They really help us understand the man."

Third: The boxed volumes help us understand that Mencken probably was not, indeed, antisemitic or racist. The references to Jewishness that I saw, even the one already cited, are made with such a casualness as to indicate the routine workings of a nonmalicious mind that has been impacted by its environment. I know that's an unacceptable argument to forward in 1991, but there it is. Cronenwett, a very smart librarian who wears bifocals and speaks in measured tones, assured me, "I don't see anything in there, nothing at all, that smacks of bigotry. He was a crusty, ethnic, German Baltimorean that's what he was like, and, I'm sorry, I just don't see him as a bigot. Not some of his friends in life were Jewish, all of them were Jewish. I say without a doubt he was not anti-semitic. And without a doubt he was not a racist."

As to that last assertion, consider an anecdote about Mencken's crusade for equal-opportunity journalism. It is told, neither as a boast nor a brag, in Thirtyfive Years of Newspaper Work: "[The] Negro community in Baltimore numbered much more than 100,000 people, yet it got next to no serious notice....I proposed that a Negro reporter be employed, and that we print occasional articles on Negro problems by intelligent journalists of the race." Mencken's lobbying with higher-ups at The Sun "went on for years," but coverage of Baltimore's black population was never extended to include much beyond murders, robberies, and fires. "To this day," Mencken wrote of the battle he fought and lost, "though the colored population of Baltimore is now approaching 250,000, there is no Negro news...save news of crime and misfortune."

ISTOOD THERE IN THE TREASURE Room at Baker, a darkly excellent place for communing with the dead, thinking about something Cronenwett had said: "These pages tell us as much about Mencken as about his subjects."

What, then, besides the specifics above, might they be telling us about him?

Let's concede right off that Mencken really was trying to get at this elusive truth, a truth he saw all around him, a truth he couldn't tell while living. He was trying to write with a pen what he earnestly felt in his heart, and that's a tough and often ruthless transcription. He knew that some of what would go in the boxes would be unpleasant. He knew this because it was inherently unpleasant material, and also because there was an unpleasant corner of his own heart. Cronenwett's defenses notwithstanding, there is an undeniable nastiness to some of the exhumed writing. There was doubtlessly a nastiness to H.L. Mencken, as well as a jollity. Mencken surely recognized this. This, Mencken would say, is The Truth.

In the autobiographies and in other joyful writings published during his lifetime Mencken celebrated his better self or so it now seems. Perhaps he was striving to fully become that person he wrote publicly about.

In the boxes, and in those Diary entries that were published in 1989, he buried a distasteful Mencken. He did this consciously, intentionally, and most emphatically These pages were shielded from view for a good long time, at the author's instructions. That's crucial, I think, to any analysis of what the newly revealed works say about him.

There are, to be sure, alternate theories as to why Mencken hid this eloquent prose.

Perhaps the writings would have made his life difficult legally and otherwise.

Perhaps the books would have hurt others. Cronenwett subscribes to this view.

But perhaps, again, Mencken was ashamed, at least a bit, of what these volumes said about H.L. Mencken.

This hypothesized shame, if there's anything to it, says something further about the man something strangely noble. Many of us actively indulge our bigotries, we exercise our dislikes. Mencken put his darkest side, as well as the dark sides of his associates, in boxes. He stashed these boxes away. He never destroyed the boxes, and he didn't want others to destroy them, not even accidentally, not even on doomsday. There were reasons for temporarily concealing the boxes, but there was no sense in denying forever the contents. What was in the boxes was truth, truth regarding the human condition or so the author felt. You can hide truth in a double-secret back room for years and years. But you must face it, sooner or later. Some day the crates must be opened, and what's inside confronted.

After storing the seven crates for 35years, Dartmouth was ready to open.

A pivotal event in youngHenry's life was when hediscovered his father'swell-stocked bookshelf.

One set of the paperscovers Mencken's 35years of newspaperwork in Baltimore.

Special CollectionsLibrarian PhillipCronenwett went on toread all 4,000 pages.

Always finding SinclairLewis either drunk orsober, Mencken didn'tlike either condition.

James Joyce's epic Ulysses was thoughtby Mencken to besome sort of a hoax.

AMERICA'SGREAT TWENTIETHCENTURY EDITOR,CRITIC, ESSAYIST,LINGUIST, GENERAL- ALL-ROUND-RULE-MAKER HAS BEENSADDLED RECENTLYWITH A DOWNRIGHTROTTEN PUBLICIMAGE.

APPARENTLY WHENVIEWED FROM THEBALTIMORE OF THE1950s, DARTMOUTHSEEMED SYNONYMOUSWITH RUSTICITY ITSELFHICKSVILLE, NH,NO ZIP NEEDED.

UNABLE TO ALTER MYVISION OF THE GREATMENCKEN TO THAT OFA WEASELLY SLEAZEBAG, I TREKKEDTO HANOVER ANDHEADED FOR BAKER.

THE BOXED VOLUMESHELP US UNDERSTANDTHAT MENCKENPROBABLY WASNOT, INDEED, ANTISEMITIC OB RACIST.

WHAT COULD BEIN THERE? MOREJUICY STUFF. I'LL BET!THIS GUY'S BETTERTHAI KITTY KELLEY!

MENCKEN PUTHIS DARKEST SIDE,AS WELL AS THEDARK SIDES OF HISASSOCIATES, IN BOXES,

Sports Illustrated writer Robert Sullivan is alsoa contributing editor of this magazine.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureHONEST TO GOD ACCOMMODATION

October 1991 By JAMES O. FREEDMAN -

Feature

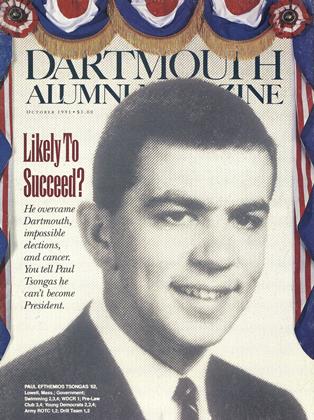

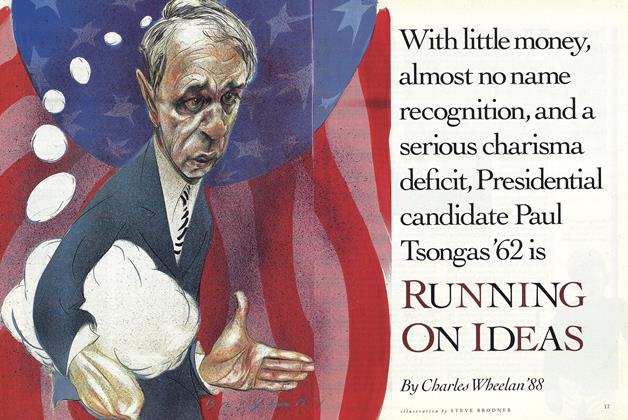

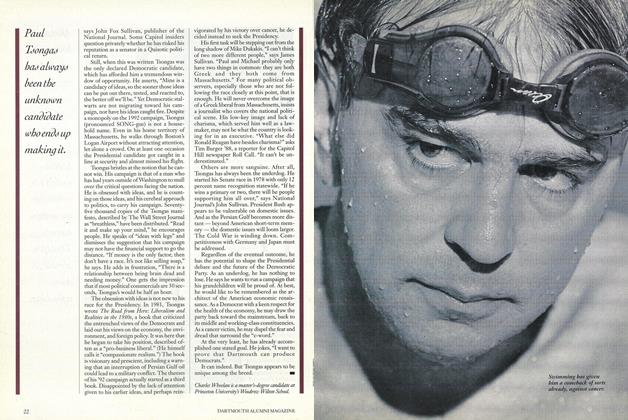

FeatureRUNNING ON IDEAS

October 1991 By Charles Wheelan ’88 -

Feature

FeatureThe Masked Stork

October 1991 By William DeJong '73 -

Feature

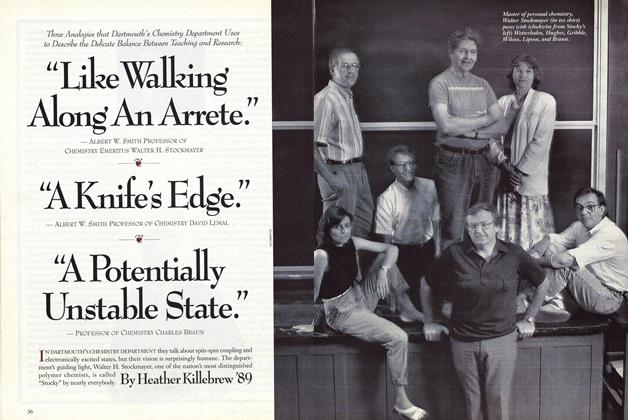

Feature"Like Walking Along an Arrete."

October 1991 By Heather Killebrew '89 -

Article

ArticleDR. WHEELOCK'S JOURNAL

October 1991 By E. Wheelock -

Class Notes

Class Notes1988

October 1991 By Chuck Young

ROBERT SULLIVAN '75

-

Feature

FeatureThe Higher-Ed Book Biz

JUNE 1991 By Robert Sullivan '75 -

Cover Story

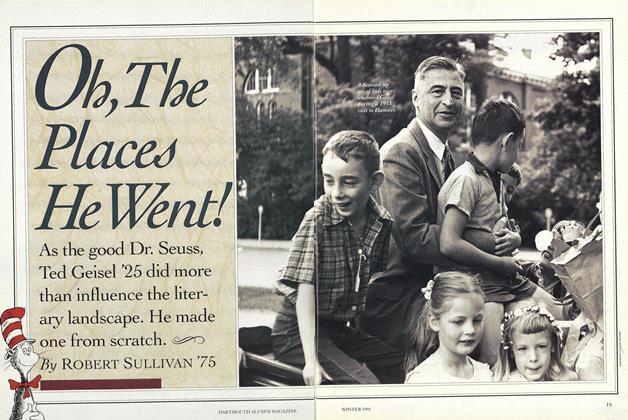

Cover StoryOh, The Places He Went!

December 1991 By Robert Sullivan '75 -

Article

ArticlePosthu-Mously, Norman Maclean Takes On a New Element

February 1993 By Robert Sullivan '75 -

Article

ArticleAn Evening with Rassias

May 1995 By Robert Sullivan '75 -

Cover Story

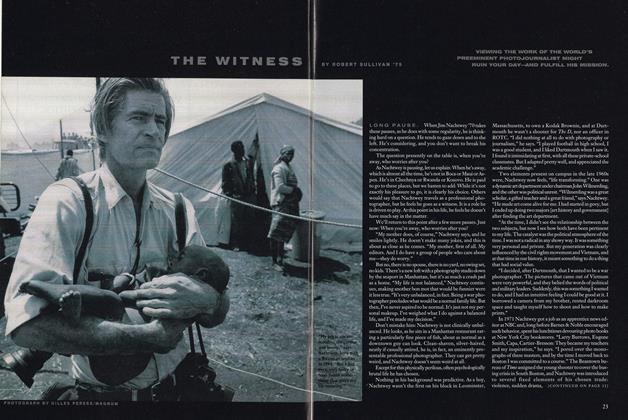

Cover StoryThe Witness

JUNE 2000 By ROBERT SULLIVAN '75 -

notebook

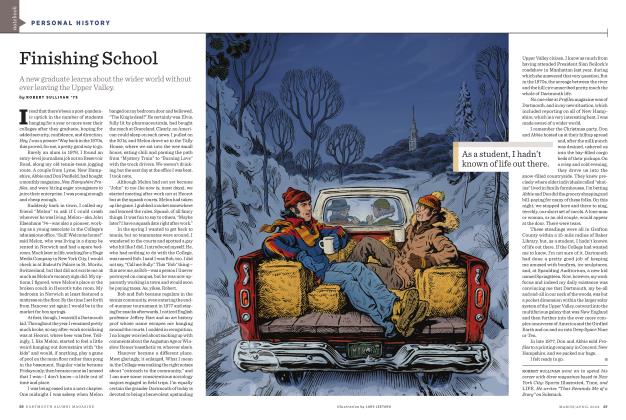

notebookFinishing School

MARCH | APRIL 2024 By ROBERT SULLIVAN '75

Features

-

Feature

FeatureThe Campaign for Dartmouth

NOV. 1977 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryCarolyn Salafia '77

March 1993 -

Feature

FeatureAlumni News

Nov - Dec By Amy Morel ’95 -

Feature

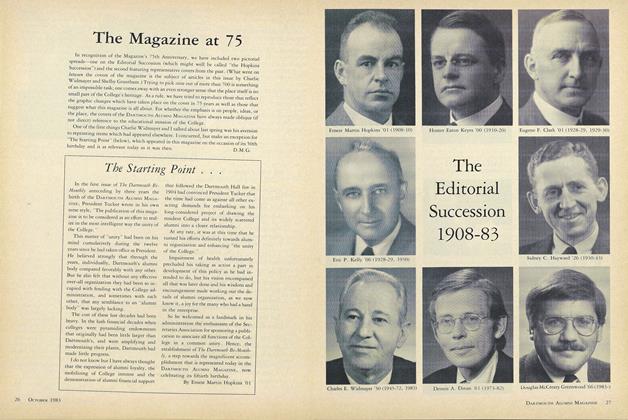

FeatureThe Magazine at 75

OCTOBER, 1908 By D.M.G. -

Feature

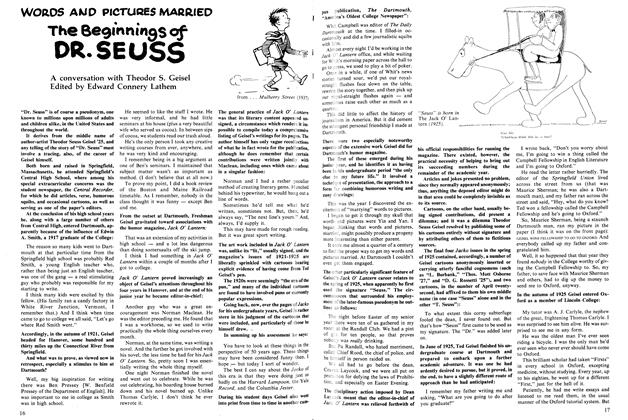

FeatureWORDS AND PICTURES MARRIED The Beginnings of DR.SEUSS

April 1976 By Edward Connery Lathem -

Feature

FeatureOn a Freshman Trip, the Destination Is Community

MARCH 1989 By Jay Heinrichs