TWINS have always held great fascination, and through the ages they have been both feared and envied. Though much has been written about them, little of a scientific nature has come from twins themselves. Most of the literature on the psychology of twins is concerned with the childhood of twins or with twins who have serious psychological problems. All too little is known about twins who grow up into successful adulthood. This autobiographical account of my relations with my identical twin brother Frank and his sudden death in 1963 is an effort to close that gap in our knowledge of twins.

The stimulus to record these experiences was a particularly striking dream in 1969, vividly documenting that an anniversary relevant to my brother's death had, until the dream, remained unconscious. I immediately wrote down the dream and associations, then reconstructed from memory as best I could the events surrounding and following my brother's death six years earlier, resolving at the same time to continue the chronicle until after the tenth anniversary of his death. Shortly I was to realize that I was reacting as well to approaching the age of my father at his death. We will see how the death of a twin illuminates what is unique about twins and twinning and perhaps what has made them throughout history objects of envy and resentment.

Anniversaries:Sudden and Unexpected Death

FRANK died suddenly from a heart attack on July 10, 1963. My father died also suddenly of a heart attack on December 12, 1928, two days before his 59th birthday and two days after Frank's and my 15th birthday. All the incidents I shall report relate to the death of my twin and the age of my father at the time of his death. My first encounter with death was when my father died. He died at home, and I vividly remember the death-bed scene and pronounced feelings of unreality for several hours thereafter. A significant residue was a nemesis complex, the idea that I, like him, would not reach my 59th birthday.

The death of my twin brother at the age of 49 came without warning and as a profound shock. Our relationship had been close, intense, but also extremely rivalrous. We were so nearly indistinguishable that even our parents often confused us. The difficulty in telling one from the other was enhanced by the fact that we dressed alike and had identical possessions. We were constant and exclusive companions, disdaining other friends until we were 12 or even older. Until we entered Dartmouth at 16, we shared friends rather than each having personal friends of his own. Lewis, four years older and our only sibling, struggled to separate us by offering attractive alliances with one or the other, but his efforts enjoyed only transient success. Socially, we retained a high degree of complementarity, I generally being the more active. Only in dating did we maintain complete independence, adhering strictly to the rule never to date the other's girl. Actually this became a device enabling me to disengage from my twin. I began to go steady at 21 and was married by 24, whereas Frank remained a bachelor for another five years.

Educationally and professionally, we pursued virtually identical careers, attending the same high school, going together through Dartmouth and Johns Hopkins Medical School and internships at Mount Sinai Hospital in New York. Not until 1941, when we were 27, did we go separate ways: Frank to Yale as a National Research Council fellow in biochemistry, I 'to Harvard as a fellow in medicine at Peter Bent Brigham Hospital. At the time of his death, Frank was professor of both medicine and physiology at Duke University, where he had established and directed the Division of Endocrinology, and I was professor of both psychiatry and medicine at the University of Rochester, where I had established and directed the MedicalPsychiatric Liaison Group. Note that both of us held dual, or "twin," professorships, unusual in those days, and that both created new academic entities, virtually simultaneously at that. Just as I at one moment could be a psychiatrist and at another an internist, so, too, could Frank be a physiologist and then an internist. Each of us as well was preoccupied with fusing two disciplines into a single entity. Such "twinning" behavior is significant: The drive is always to be two, yet be unique from all others.

My reaction to news of Frank's death was stunned disbelief, followed some 20 minutes later by tears. On the plane to Durham, North Carolina, within a few hours, I experienced chest pain, and a number of vivid dreams occurred in relation to the funeral. The details are now forgotten, but the dreams were all marked by a pronounced feeling of confusion between myself and my brother, leaving me as I awoke for a moment unsure which one I was. On my return to Rochester a week later, I had a medical examination that demonstrated evidence of coronary heart disease, although there was no indication that the pain on the way down had represented a heart attack. I assume it was a conversion, or psychogenic, symptom, but the idea became firmly fixed in my mind that I too would soon suffer a heart attack and die. The date for my nemesis had been advanced!

The Prediction Fulfilled:I Suffer a Heart Attack

THE months following Frank's death were marked by profound mourning, but not so intense as to interfere significantly with my family or professional life. As time passed, I found myself increasingly entertaining the magical notion that if the heart attack did not occur by July 10, the first anniversary of his death, I would survive. I was quite aware of the irrational nature of this idea, but I was unable to dispel it. On June 9, one day short of 11 months after my brother's death, the longanticipated event occurred.

The circumstances were notable. Just one week earlier, I was the speaker at the annual banquet of the graduating class at the medical school. I had prepared a humorous talk on clinical observation which included photographs of my brother and myself at various ages, a subject I knew would be entertaining, for the students had always enjoyed my twin stories and Frank had lectured to this same class two years earlier. Why I had prepared such material is not clear; I can only conjecture that I was in some way attempting to carry on the work of mourning. As an exercise in the fine points of clinical observation, I was emphasizing our identity yet calling on the audience to distinguish between us. Although I seemed determined to accentuate the humorous aspects of our relationship and avoid dealing with the sadness of my loss, I was vaguely aware of an uneasiness about whether this was appropriate even though the dinner was traditionally informal and attended mainly by students, most of them well in their cups before the evening's speaker got to his feet.

I was taken aback upon my arrival to find that this time it was to be a formal occasion with a large number of faculty members, the dean, and the newly ap- pointed president of the university in attendance. My first thought was that my intended remarks were too personal and most inappropriate. Abruptly, I became acutely anxious, the first genuine anxiety attack I had had for many years. Intense anxiety, typical of the stage fright I had experienced occasionally in younger years, persisted throughout dinner and until I got up to speak. Actually, my remarks were greeted with all the amusement I had anticipated, and the evening ended well.

Arriving home, however, I found some unpleasant news. Some difficult problems had arisen involving a person closely iden- tified in my mind with my twin, and it devolved upon me to attempt some resolution. We arranged that he come to Rochester for a meeting on the evening of June 9. It was a meeting I did not look forward to, and, in retrospect, I realize that I kept myself unusually busy that entire week and especially on the designated day, avoiding thinking about the confrontation. But it never took place. At 3:30 that afternoon, the coronary attack began!

My reaction to the attack was great relief. I felt serene and tranquil. Not only had I escaped the unpleasant meeting, but I no longer had to anticipate the heart attack. The other shoe had fallen. A number of dreams involving confusion between my brother and me followed in the next few days, but I recall no details. Then a curious episode occurred. I was listening to a performance of Hamlet on my bedside radio in the hospital when I suddenly thought I had achieved remarkable new insight into the play: Hamlet's uncle had not slain his brother; that was only Hamlet's fantasy. I was astonished that I had never ap- preciated this "fact" before, and I felt exhilarated by the discovery. Of course, I quickly realized my error and easily recognized its implications. I was not responsible for Frank's death after all! I left the hospital July 1, convalesced at home for a couple of months, then returned to a full schedule.

Fifth Anniversary of the DeathDream 1: Anxiety

OVER the succeeding years I became less and less preoccupied with anticipation of the significant anniversaries, especially of our birthday and Frank's death. Yet a number of incidents served to keep alive the conflicts for myself and for others over the fact that I, not he, had survived. On a visit to Duke in 1965, to address the Frank Engel Society, an organization established by his colleagues to honor my brother, I was several times cheerfully greeted as Frank in the hospital corridors by persons apparently repressing momentarily the memory of his death. The president of the Engel Society even made a slip and introduced me as Frank. Such occurrences in the past had always been a source of amusement. After his death they became painful.

Hence, all the more remarkable was an occasion in 1968, when I casually responded to such a greeting, only to realize with amazement a few minutes later that I had been called Frank by a stranger and yet had felt no surprise. But the setting was important. The occasion was when I was to be presented with the Menninger Award by the American College of Physicians, an organization in which Frank had been prominent but of which I was not even a member. It was a perfect setting to play out our rivalry. Clearly, my wish that he could share (and be put down by) my success was intense enough that for the moment at least I accepted the stranger's error as if Frank were indeed still alive.

As June 1968 came to an end, I did not have in mind the fifth anniversary of Frank's death until the following dream occurred:

I have returned to Cincinnati, where Ihad been on the faculty from 1942 to 1946,to give a lecture. I am late and cannot findmy way, even though I am very familiarwith the hospital. There seems to havebeen new construction so that I keep encountering obstacles to the familiar routes.The fruitless search seems interminable,but eventually I get to the lecture room,only to discover that I have forgotten myslides and manuscript. The feeling in thedream is of anxiety and urgency, my legsare weak, and I have difficulty seeing. Iawaken feeling uneasy but then relievedto recall that a few months earlier I had infact given a lecture in Cincinnati and it hadbeen a great success.

This was a recurring kind of dream that I had come to as'sociate with the anticipation of something unpleasant and therefore usually attempted to analyze. Freud had called these "examination dreams" because in them the dreamer is commonly experiencing great anxiety about some forthcoming examination or obstacle only to become aware on awakening that the examination was in fact one already passed with flying colors hence the feeling of great relief. As I roused myself, I could think of nothing relevant. Then, gradually, with no little surprise, I realized that I had not thought at all about the approaching anniversary, July 10, of my brother's death. But the dream had occurred not on July 10, but on July 1, a date for which I could at first find no significance. But turning to the 1964 appointment book where I had recorded medications and visitors following my coronary attack, I learned to my surprise that it was the date of my discharge from the hospital. The significance of the dream then became clear: The unpleasant fact that I had to face was the guilt I felt that I had returned home alive while my brother had not. The dream characteristically condensed the pain of guilt and loss over Frank's death and the relief at my own survival.

The next episode, also a dream, occurred a year later, in 1969:

Fifth Anniversary of the AttackDream 2: Death and Depression

I meet a colleague who tells me he is going to take a position at Yale, where itseems that I, too, am going. He informsme that Gene Ferris will be there as well. Ibecome exhilarated, for Gene and I hadworked together productively and harmoniously years ago in Cincinnati. I exclaim, "That's great! That's marvelous!We'll be able to do the study of A CTH andgrowth hormone responses to viewing theAberfan film." Then all of a sudden Iremember that Gene is dead. I become sadand agitated and try to point out this factto my colleague, who looks at me with acondescending smile, as if I were making afoolish error. "Don't you remember?" Iask. I walk away from the scene withanother colleague, to whom I try to explain the situation, but he assumes atherapeutic guise, as if I am suffering somekind of delusion. I awaken feelingdepressed.

The associations to this dream come quickly. It was Frank, not I, who had gone to Yale; it was he, an endocrinologist, not Gene Ferris, a cardiologist, who could have helped me with a problem involving growth hormone and ACTH. Clearly, the dream once again alluded to the fact that my brother had died and I had survived. At that point in my associations I abruptly realized that the dream had occurred on June 9, the fifth anniversary of my own coronary. This was a very important anniversary to me, for ever since the original attack I had kept in mind a medical report that people who survive a myocardial infarct without complications for five years thereafter enjoy the same life expectancy as those of the same age who had not had a coronary. Hence, I had been looking forward to June 9 as a date to celebrate. How was it then that that critical date had not been in mind in the preceding weeks? The long-awaited day had arrived, and yet I had awakened totally oblivious of it. Why? The answer was simple. Two and half months earlier, I had suffered a minor attack of coronary insufficiency, and that at least in my own mind had been enough to exclude me from the magic circle of those statistically restored to normal life expectancy. Consciously I had eliminated the date from my mind; un- consciously in the dream I had restored my brother (and thereby myself) to life only once again to take it away.

There are a number of other pertinent associations. The fusion of our identities and the yearning for reunion are clear in two items: my going to Yale, which Frank in reality did; and my anticipation of collaborating with the endocrinologist, though he was Frank in reality, not Gene as in the dream. The Aberfan film, a documentary on the grief responses of the survivors of a disaster in which over 100 children lost their lives, had a profound emotional impact, and we were using it to study the endocrine responses to sadness so provoked. Even after a dozen viewings, the film still moved me to tears. In the dream I will overcome this painful reaction to un- resolved grief by being reunited with Frank. Actually, Frank and I had dis- cussed, at our last meeting before his death, which took place at the 25th reunion of our medical school class, collaborating on a book which would in effect have com- bined his endocrinologic and my psy- chologic insights. The thwarting of this aspiration was one of the more anguishing consequences of his death.

In the dream we measure growth and ACTH, whereas in fact the actual research involved growth hormone and Cortisol. The error is significant because, years earlier, I had adduced evidence that ACTH produced effects on the brain. Frank dissuaded me from publishing this because we had not adequately controlled for impurities in the commercial preparation of ACTH. Ten years later, however, at our final meeting, he told me triumphantly that he had just proved such effects, and we made plans to repeat the study, now with proper controls. In the dream ACTH simultaneously symbolizes my triumph that I, not he, had first discovered the effects and my resentment that he had cheated me of my scientific priority. This exactly paralleled my childhood resentment; he was the first, i.e., the oldest (by five minutes), whereas I liked to fantasize that we had been mixed up at birth and I was really the first born. The ACTH also symbolized my pleasure at reunion (rebirth) in that we would finally collaborate. These are themes important to the psychology of twinning.

Gene Ferris symbolizes the similarity of opposites, also a twin theme. Furthermore, his initials G. before F. correspond with the earlier theme, George before Frank. Although Gene was ten years older than I, we had enjoyed an extremely close and fruitful relationship. I often thought how unusual this was, with our backgrounds so very different he the product of an old Mississippi plantation family; I the son of a Jewish immigrant, born and raised in Manhattan. His sudden death in 1957 had shocked me. We had begun in a father-son relationship, but there quickly evolved a more complementary sibling relationship, providing in the dream-work a link between my father's death, my brother's death, and my concern about my own death.

The significant anniversaries of 1970 came and went with no occurrences worthy of note, and I thought perhaps the work of mourning was at last complete. But events of 1971 and 1972 were to suggest a continuity between haunting thoughts of my own death and the deaths of loved ones in the past.

More Anniversaries,More Ghosts

IN May 1971, my wife accompanied me to Atlantic City, to a meeting that happened to coincide with the annual meeting of the American Society for Clinical Investigation, an organization of which Frank and I had both been members since the 19405. For many years he and I had reserved this time for an annual reunion. (Atlantic City was also much associated with our childhood, with visits there to a beloved grandfather.) After Frank's death I never again returned to Atlantic City until that trip with my wife, when I found myself reconstructing for her scenes and circumstances of his and my reunions there. How often his students and colleagues and mine would mistake me for him and him for me! My reverie was unexpectedly interrupted by a greeting from an old acquaintance, a man who had known the three Engel brothers at Hopkins in the thirties and for more than 25 years had been a close colleague of Lewis' on the Harvard Medical School.faculty. When he commented, "I had dinner with your brother a couple of weeks ago," how astonishing that I should ask, without a second thought, "Oh, really, which one?" A curious error indeed, for even had Frank been alive, I would have known at once that he was referring to Lewis, not Frank. Clearly, in the nostalgic mood evoked by Atlantic City, my longing for my lost twin became so intense that even eight years after his death he was for the moment very much alive.

A month later, I was again the speaker at the medical school graduating-class dinner, an occasion which, in 1964, had been followed one week later by my heart attack. I was aware of a vague sense of ap` prehension, but the week passed uneventfully and the coming anniversary actually slipped out of mind. But on the afternoon of June 9, while talking with a fellow in my office, I abruptly became so fatigued that I felt like discontinuing the session on the spot. I had planned to go on vacation in some ten days' time, but on the spur of the moment I decided I had been working too hard and should begin my vacation at the end of that very hour. Instantly, my spirits lightened, and I felt as though I had been relieved of a terribly oppressive burden. My wife was amazed when I arrived home early, on vacation at that, for such impulsive action is quite uncharacteristic. I slept well that night and the next morning at breakfast, virtually out of the blue, the thought popped into my mind that the seventh anniversary of my heart attack had come and gone without my even thinking of it. Then with astonishment it came to me that the abrupt development of fatigue the day before had occurred at 3:30 p.m., virtually seven years to the minute of the onset of my coronary attack. That day, too, I was in my office, and I remembered as well the surprising sense of relief, even peace, that the long-anticipated heart attack had at last come. I was to have a vacation from the oppressive sense of guilt that I was in some way responsible for Frank's death. Maybe even death was to take a holiday.

What could it mean that these events so powerfully affected me, that I should even momentarily behave as though Frank had not died; that I should re-enact so precisely my own scrape with death? Before the year was up, events were to reveal that I had more ghosts to exorcise.

Age 58 the Year of NemesisDream 3: Triumph and Euphoria

On my 58th birthday, in 1971, 1 thought to myself, "Next December 10, you will be 59. That will begin the year to worry about. Father was 59 when he died." But the attentive reader will recall that my father was 58, not 59, when he died. The dates of my father's birth and death had always been very clear in my mind he died two days before his 59th birthday yet curiously I now had no question that he had died two days before his 60th birthday. Thus, I ushered in my "nemesis" year by repressing the significance of my reaching the age of 58, even though that number had been in my mind for 43 years.

More and more during that year thoughts of my father came to mind. He would be pleased, I decided, with the way this son had turned out despite some uneasiness he had about some aspects of my childhood behavior. I became aware of subtle evidences of identification, a striking confirmation occurring in London that spring of 1972, when my wife took a candid snapshot of me. It turned out uncannily similar in pose to one I had taken of my father when he was 58. Was there an anniversary significance to my assuming that pose, a strange one for me, in April of that year? A search of old photographs yielded a picture of my father along with photographs of Frank and me in the same pose, also taken that same April day in 1928. On film are my father, my twin, and myself in identical poses, a pose I replicate 44 years later. The question arises: Had I unconsciously begun to fuse the images of my father and myself? (On the same London trip, I bought myself a cap. My father wore a cap, and walking down the street I saw my shadow in front of me and had the uncanny feeling that I was seeing my father's shadow.) Until then, the confusion was always with Frank. Could it be that in my unconscious my father was becoming my twin?

On October 17, 1972, the following dream occurred:

I am taking an examination, an oral examination held in a conference room witha number of examiners seated around atable. I am asked, "What is thepaleothallium?" I have no idea, but I smileto myself and then say, "I do not knowwhat it is, but I know where to look it up.And that's good enough!" I then lookaround the table and say, "I'll bet most ofyou don't know, either." Several of the examiners nod in agreement and smile. Iawaken feeling triumphant and withlaughter report the dream to my wife.

My first association is that this is the ex- act opposite of my typical examination dream, that I am facing not an unpleasant prospect but something favorable. I associate the scene in the dream with the oral examination I took for my internship in 1937, a triumph in that I ranked first among several hundred candidates and Frank second. As I entered the room for that examination I was extremely apprehensive, but I felt relieved immediately when I realized I could answer the first question easily. But my confidence was quickly undermined when I noticed one of the examiners shaking his head in apparent disapproval. Disaster seemed imminent until I was able to regain composure by indulging in an outrageously narcissistic fantasy he was shaking his head not in disapproval but in awe at my superb answer! When I finished, he did indeed pronounce my response to be excellent, and only then did I recognize that his head motion was a tremor. I felt relief and triumph, as I did in the dream.

No further productive associations came to me at the time, but the euphoric mood persisted throughout the day. From time to time, I thought happily of the dream, even giggling to myself. Then, later in the day, it occurred to me suddenly that my father wasn't 59 when he died but 58! I was astonished, bewildered. How could I possibly have made such an error? Then I realized that rather than having a whole year to spend in apprehension, I had already survived ten months beyond the fateful 58th birthday. And I understood my sense of triumph in the dream. At the examination, I knew my answer was cor- rect, even though one examiner seemed to be telling me I was wrong; in the dream, I felt I did not have to know everything, that it was sufficient to know how to find the answer. Furthermore, the examiners, my elders, nodded their heads in agreement that they could do no better. For reasons I did not then understand; the danger of be- ing 58 had abruptly lessened. The repres- sion had lifted, and I could recognize that it was becoming 58, not 59, that I had so long dreaded.

Although there are no further notes for that October, the reason that the repression had lifted became suddenly clear as I assembled this record the following summer. Beginning in September 1972, I had begun having some ominous symptoms progressive weakness, fatigue, exertional breathlessness, and episodes of rapid heart action. The periodic bleeding from hemorrhoids I had experienced for many years had recurred, but I paid no heed since it has never led to anemia. Despite such obvious symptoms of anemia, that possibility never crossed my mind. I did not consult my physician, but meeting me by chance on November 2, he expressed alarm at my pallor. My anemia from chronic blood loss and iron depletion turned out to be severe enough to justify immediate hospitalization and the transfusion of two units of packed red cells. I felt remarkably better within two weeks, by then aware of how surprisingly far I had allowed my health to deteriorate.

With this, the full motivation for the dream became clear. I had been denying to myself the seriousness of my developing illness, symptoms of which were in fact threatening to undermine the repression of my fears about becoming 58. The dreamwork effected a compromise. In the manifest dream, I say triumphantly that I don't have to know, that I will survive anyway. My association is to an examination in which apparent disapproval did not mean what it seemed to and from which I emerged triumphant over my brother. Once again, the theme of who comes first appeared; to outdo my twin meant to achieve my own individuality, to be the favored one, and in the dream, to escape death.

But was it only that I was denying illness? Or could it be that I was passively accepting illness as a deserved fate, just as eight years earlier I had passively accepted my heart attack? In retrospect I realize that in a perverse way I was secretly experiencing a kind of grim satisfaction with my symptoms. But a fuller answer requires a better understanding of what is unique in the psychology of being a twin.

Psychology of Twinship: I amGeorge; I am also Frank and George

FROM birth the fact of being one of a pair decisively alters the development of one's inner sense of self. One is not just an "I"; one is also a "we." Indeed, the earliest appreciation of self is likely to be more "we" than "I," for it is to the twins that the world responds, not to the twin. The twinship is reinforced; the individuality of each is slighted. Throughout much of our childhood, even well into adolescence, our parents as well as others referred to us collectively while often misidentifying us as individuals. We were dressed alike, provided with identical possessions, and from earliest infancy we spent far more time with each other than with anyone else. I was virtually never alone; we were often alone. For us, to be "alone" meant to be alone with each other.

I never comfortably addressed my twin as Frank, nor did he address me as George. Until well into adulthood, we called each other by the same name, "Oth" short for "Other Man," usage that emerged with spoken language in our second year. A shared name is not uncommon among twins, and in our case the meaning of "Other Man" was certainly an acknowledgement that each of us was successfully differentiating himself from the other one, an essential first step in achieving a sense of individuality: I am I; he is the other. But by the shared name, we also maintained our dual twin identity. To the rest of the world, we presented ourselves as two "Oths," not as a Frank and a George. (Interestingly enough, small children, meeting Frank and George, com- monly responded, "No, two Franks" or "Two Georges.")

Patently, the advantages of functioning as a unit are considerable. Twins have been called "a gang in miniature," and even when very young we could gang up on others. I recall vividly our glee, when we were only two, in enticing our four-yearolder brother close enough to the bars of the playpen to seize him by the hair as he screamed helplessly like Gulliver in the hands of Lilliputians. The narcissistic gratification of being twins was reinforced repeatedly not only by the attention directed at us as twins but even more by the extraordinary power we felt in our ability to deceive our elders as well as our peers. Together we invariably attracted attention; alone we could provoke mystification at will.

Even Dartmouth officialdom was more than once deceived. Neither of us, for instance, passed the swimming test, in our day a requirement for graduation. Miserable swimmers at best, we artfully contrived to jump into the pool simultaneously from opposite ends and, in the confusion, to join those already swimming the return length. I jumped in as George and emerged a pool's length later as Frank, with the monitor none the wiser. The test was passed by the Engel twins, but by neither Frank or George. Let the record be so amended.

Non-twins find it difficult to appreciate the omnipotence inherent in this ability to influence the behavior of others, especially one's elders. Its perpetuation as a reservoir of narcissistic pleasure was evident in our delight in forever telling twin stories. As twins mature and succeed in establishing their own separate identities, the advantages and gratifications of twinship do'not necessarily diminish. They may indeed increase and become manifest in other ways also difficult for non-twins to understand, much less accept. For us this was expressed in our professional careers and our scientific work by holding dual professorships and forever striving in our teaching and writing to bind together separate disciplines and ideas, to stress resemblances as well as differences that is, to twin.

"I love my twin to death" Hostility Between Twins

MOST people justifiably envy the special closeness between twins, but they err in imagining it to be quite free of hostility. The problem for each twin is to assert and thereby achieve individuality without losing the advantages of the twinship. Ultimately, this comes down to controlling and regulating aggression. As children Frank and I worked out an elaborate system of equivalent but tempered aggressive behavior. Were one even accidentally to bump the other, then the victim had the right to return an exactly equivalent bump. Establishing equivalency was the rub; little imagination is required to see how retaliation for such "accidents" could escalate. But such aggressive play was not without enjoyment and only rarely got out of hand. It served both to defuse the intense rivalry between us and to es- tablish boundaries between the"I" and the "we."

Our rivalry was indeed intense, for periods even all-consuming. As children we competed for the attention of our parents and brother. Though both parents tried to be even-handed, I nonetheless nursed the notion that Mother gave priority to Frank because he was older (by five minutes!), which intensified the impor- tance for me to be "the first" in almost anything. Our brother tried to exploit our rivalry by aligning himself first with one and then with the other. Under such circumstances, our carefully monitored non aggression pact broke down completely, and the excluded twin either submitted passively more often Frank or engaged in violent attacks on the others more often I.

Once in a fit of rage at being excluded, I pursued my brothers with a carving knife and had to be disarmed by the cook. That evening Father announced solemnly that if George did not learn to control himself, he would surely grow up to be a criminal. He then took Frank and Lewis to see Douglas Fairbanks in The Three Musketeers while, as punishment, I was confined to my room. There, with great satisfaction, I re-enacted the attack over and over again in front of the mirror. Never again would "George the Ferocious" (G before F) be confused with "Frank the Shy"! How appropriate the mirror, using my own image as my twin. Let no one doubt that, in my mind at least, a murderous impulse was at work. That it would return to haunt me is evident in my fatalistic expectation that I, too, would suffer a heart attack and die within a year of Frank's death and in the Hamlet error a few days later, an effort to convince myself that I was not responsible for his death after all.

For twins, successful maturation means that each achieves autonomy without sacrificing the advantages of twinship having their cake and eating it too an enviable state reached by most by midlife. While each twin establishes his own life and his own family, the twin bonds are sustained over time and distance. There comes a definite period for many twins when, by choice or circumstance, each begins to strike out on his own, the dominant one usually setting the pace. For us, it was at Dartmouth, where we resolved to live apart and each to develop his own circle of friends. Meeting my future wife in 1935 and our marriage in 1938 secured my autonomy; Frank's came somewhat later. Thereafter, though we were each involved with family and career in different places, the drive to sustain the duality was ever present. As each became established, our rivalry was attenuated, and narcissistic enjoyment of each other's achievements became possible. With success, to be mistaken for Frank was no longer a threat to my individuality; I could enjoy the double pleasure of being mistaken for the wellknown Dr. Frank Engel, only to identify myself as the equally well-known Dr. George Engel. The childhood games were played out to the very end I could even pass myself off as an endocrinologist with an exceptional knowledge of behavior.

Death ended this steady flow of twin-associated gratifications. Indeed, for a period they turned to ashes. I lost all pleasure in recounting twin stories. To no longer be a twin was as much a loss as to no longer have a twin.

Reunion and Immortality orPunishment and Obliteration?

THE critical anniversaries related to the death of my father as well as of my twin. The dreams and other occurrences clearly reflected my concern over my own death or, more accurately, over how to ward off my death. My father's death had planted the seed of a nemesis complex in the form of the occasional fleeting thought that I would not live longer than he had, and my twin's death gave immediacy to the old idea. I resentenced myself, so to speak; I would die within the year. Again, as in our formative years, the issue of separateness and unity was joined. Upon Frank's death, to be separate was to live, to be joined was to die. The battleground was in the unconscious, where boundaries between self and twin representations were fluid and where time and numbers were used in symbolic and magical, not chronologic and metric senses. In the unconscious, time repeats itself rather than moving inexorably on.

In this psychodynamic situation, calendar time in the form of anniversaries became the outside stimulus ever ready to reawaken the mortal life-and-death struggle, the link between external time and the unconscious time sense. The significant anniversary dates either did not become conscious or were repressed as they approached. The danger in acknowledging the anniversary significance of these dates was the spectre of death with its double meaning. Death meant reunion, the re-establishment of the longed-for and valued dyad, the twin unit, and death meant suffering retribution for my own fratricidal impulses, as the Hamlet error revealed. The first implies immortality, the second obliteration. In the ACTH dream I anticipate great scientific achievement (immortality), only to have to acknowledge that Frank's death obliterated the possibility. Clinging to statistical reports of a normal life expectancy for those surviving five years after a coronary was only a thinly disguised wish to live forever as writing this article must be.

Clearly such preoccupation with time bespeaks preoccupation with death. So it is not surprising that the nemesis concept of my 59th year should become intensified and require the defensive maneuvers that transposed the fatal age from 58 to 59. But another important process was at work. When I reached my father's age at the time of his death that is, when I became 58 he and I, in the illogical thinking of the unconscious, became twins. I put forth as evidence the photographs taken of each of us at 58 and the uncanny feeling I had when the similarity struck me. We see how the unconscious wish to be reunited with my twin combined with the long-dormant nemesis complex to reactivate the unconscious struggle over whether I was to live or to die. The defensive displacement of the fatal age from 58 to 59 easily drew support from two other historical facts: My father had survived all but the last two days of his 59th year, making it easy for me to think of him as 59; and his death occurred two days after my (our) birthday. Thus, with my birthday and my father's so close together, we were almost twins.

In sum, the unconscious wish to reestablish my twinship simultaneously provided material for both sides of the conflict. My father and I had become twins, and I could use the confusion of identities to transform the dates, thus protecting myself from recognizing that the time for my self-imposed death sentence was at hand. The sense of pleasure, even triumph, experienced during and after the successful examination dream, that anticipated acceptance of age 58, reflected the feeling of inner harmony. For the moment at least, I had placated my archaic conscience by falling back on the narcissistic gratification of reunion with my "twins" (brother and father), thereby sharing their fates with pleasure. For now death would mean the longed-for immortality, not the dreaded obliteration.

CAVEAT lector let the reader beware! Derivative as it is from fragments of self-analysis, everything here written must be regarded as data. Indeed, perhaps the most prudent, the most rewarding attitude is to consider this article as though it were the manifest content of a dream that has already undergone secondary revision in writing. In this sense everything is data the form and sequence of the presentation, the formulations, the omissions and elisions so immediately detectable, even the motivation to write this in the first place. The last should be the most transparent of all! To the extent this is well received, I have reestablished the narcissistic gratification of the lost twinship. I can again enjoy being a twin and telling twin stories. And this may be the best story of all.

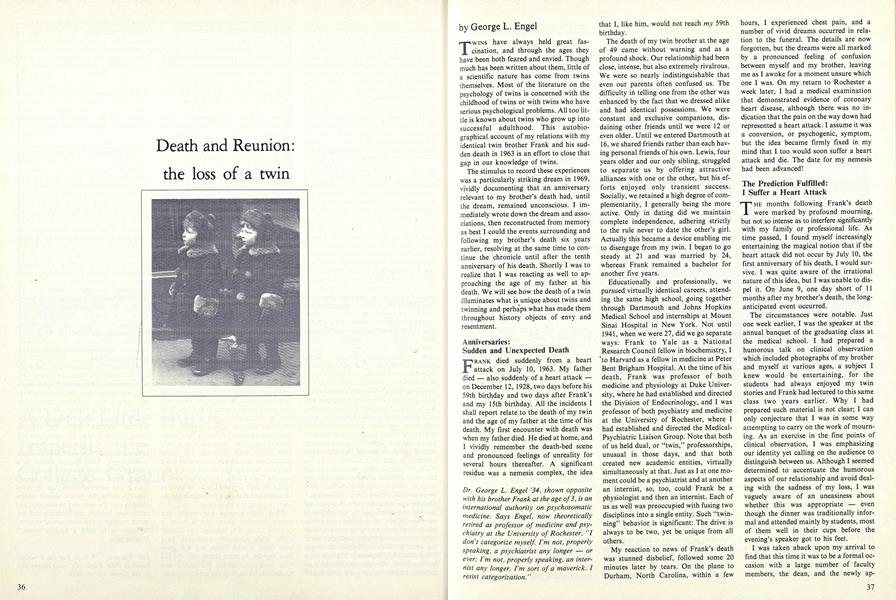

From infancy through late adolescence, "to be 'alone' meant to be with each other.

"One of the boys wears a cocked hat aroundcamp all the time." Yes, but which one?

At the age of 14, Frank and George strike a familiar family pose. See also page 42.

The author (above) and his father at theage of 58 (in April 1972 and April 1928).

Opposite: George Engel today, survivorof the "battleground of the unconscious."

Dr. George L. Engel '34, shown oppositewith his brother Frank at the age of 3, is aninternational authority on psychosomaticmedicine. Says Engel, now theoreticallyretired as professor of medicine and psychiatry at the University of Rochester, "Idon't categorize myself. I'm not, properlyspeaking, a psychiatrist any longer orever; I'm not, properly speaking, an internist any longer. I'm sort of a maverick. Iresist categorization."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

Cover StoryThe Long-Deferred Promise

June 1981 By Shelby Grantham -

Feature

FeatureRockefeller Center: the ideal of reflection and action

June 1981 By Donald McNemar -

Feature

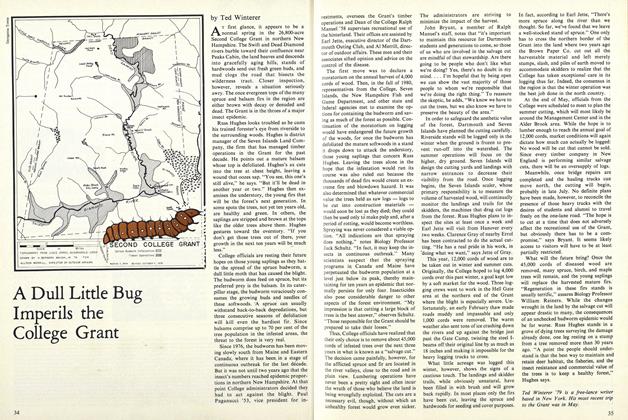

FeatureA Dull Little Bug Imperils the College Grant

June 1981 By Ted Winterer -

Article

ArticleDartmouth Authors

June 1981 -

Article

ArticleThe National Committee

June 1981 -

Books

BooksWhat If?

June 1981 By R. H. R.

Features

-

Feature

FeatureReport on Trustee Organization

October 1959 -

Feature

FeatureTHE STUDENTS COME FIRST

DECEMBER 1962 -

Feature

FeatureThe Quotable Vet

Sep - Oct -

Feature

FeatureFree Ride

Jan/Feb 2010 By ED GRAY ’67 -

Feature

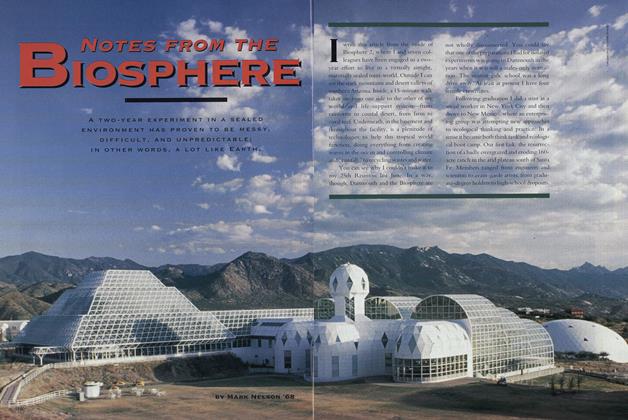

FeatureNotes from the Biosphere

October 1993 By Mark Nelson '68 -

Feature

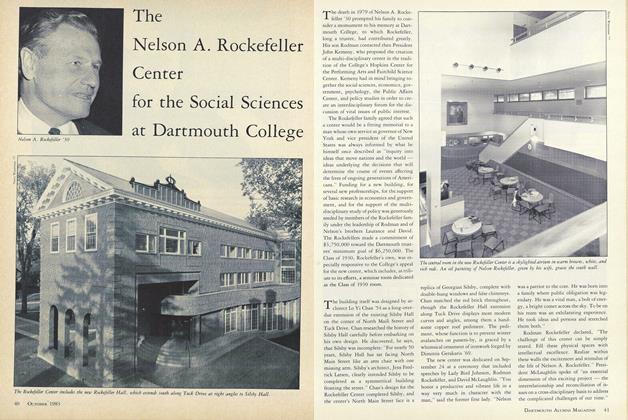

FeatureThe Nelson A. Rockefeller Center for the Social Sciences at Dartmouth College

OCTOBER, 1908 By Shelby Grantham