And Mensch

BEFORE passing it on to my successor the other day, I was looking again at the handsome souvenir program for the opening of the Hopkins Center in November of 1962. It is interesting to reflect that while the entire cast of characters has changed, almost everything that was written then is still entirely valid. Given my current preoccupation, one passage hit me with particular force. In his message of good wishes, that wonderful man Goddard Lieberson quoted Thoreau: "If you have built castles in the air, your work need not be lost; that is where they should be. Now put the foundations under them." With those words in my mind it was easy to decide to devote the first of these familial essays to something of what's been going on in the planning for the Hood Museum.

The whole story began about ten years ago, with the first time anyone put pen to paper to make the case that what had been provided in the Hop for the storage and display of works of art had by then achieved a state of inadequacy. But it would be a mistake to go that- far back, just as it would to those more recent years in 'which arguments were refined, cases proved, and approval-inprinciple won. To all intents and purposes (what a lovely phrase that is!), the story of the Hood Museum as we shall actually enjoy it began on April 13, 1981.'

On that date our building committee began to interview architects. In the course of three days we met the six who had survived all the discussions as we whittled down the list from the many dozen names that had been in the hopper to begin with. Those 12 hours of interviews were undoubtedly among the most enjoyable of all the tens of thousands of hours I have spent in Hanover, and for all of us on the committee they brought something of a revelation in terms of how six different sets of intelligences could approach the same data.

All six firms have major reputations, and at least three of them are solidly established internationally. Five are American, the other the foremost German architect of the day. Three of the six came to case the place ahead of time (in two of those visits it was senior partners who did the casing), while the other three based their presentations on the written material we had sent everyone and on their first walk around the campus. One came with an amazing set of cardboard cut-outs; another with slides taken from photographs in the College archives which none of us locals had ever seen. The contrasts in their style and appearance were (not surprisingly, after all) as marked as the contrasts in the style and appearance of the buildings they have designed. The spectrum from tweeds and a home-knit sweater to the

severest cut of business suit was one thing; the range of tones of voice from friendly conversational to heavily dogmatic was another; and so was the difference between arriving in a chartered jet and driving up in a crowded old car. But the layout of the interview sessions was common to all: a time for the architects to show slides of their work and tell us about their respective modioperandi; questions from them to us and from us to them; a chance to say something preliminary about the problems our project presents, and about their first thoughts as to how they might be tackled.

What a lot we learned. And what a complicated time we had of it analyzing our reactions, knowing (as we readily agreed we did) that any one of the six would produce a notable building in response to our challenge. But a firm consensus emerged quite promptly that Charles Moore and his colleagues had grasped in a tellingly sophisticated way which elements in this particular, undertaking constituted its fundamental uniqueness.

Within a matter of days arrangements were being made for the next step in the well-ordered process: visiting some Charles Moore buildings, interviewing other clients, and spending time in further discussion in the setting of his studio. (I suspect that at this stage we all felt a small pang of regret that we had not included the German architect in the running during this visiting stage.) Small problem: Charles Moore, before and after his years as dean of architecture at Yale, had taught and worked mainly on the West Coast, and buildings by him east of the Mississippi are not very numerous. Good solution: talk with the people at Williams College for whom he had just completed the design of a new museum linked to an existing building on a very constricted site, and visit an apartment building in New Haven built as public housing for the elderly. If we were still in doubt we could always go on to some of his famous California commissions.

Again we learned a lot, and one thing we learned most convincingly: Charles Moore is not just an architect, he is an exceptionally intelligent and sensitive man who listens to his clients and comes to care as they do about the purposes, fundamental and specific, which their building is to serve. At first, the visit to the housing project seemed barely relevant, something done because of the exigencies of time and space. In the end it may have proved decisive, and the reason for that is encapsulated in the fact that the residents of that so-sympathetic complex dedicated a fountain to him, and that the plaque on it says that it is for "Charles Moore: architect, friend, and mensch."

Through the summer Moore's brilliant young colleagues (one of them, most happily, a Dartmouth alumna from the famous class of 1976) were getting together a mountain of material for his first threeweek stint in Hanover, a time of intensely stimulating discussion which will come to an end, all too soon, when the crucial decision about where to site the Hood is made early this fall.

I would find it very hard to think how I could have had a more satisfying coda to my formal involvement with the arts at the College than the one I have taken such pleasure in during the last few months. I envy my successors in the detailed planning and design stages as they continue to get to know and to enjoy a university man of rare quality, and share with him the exhilaration of putting some foundations under our wonderful'castles in the air.

Peter Smith, for 12 years director of theHopkins Center, a job he concluded inAugust, begins a monthly column for the ALUMNI MAGAZINE with this issue.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

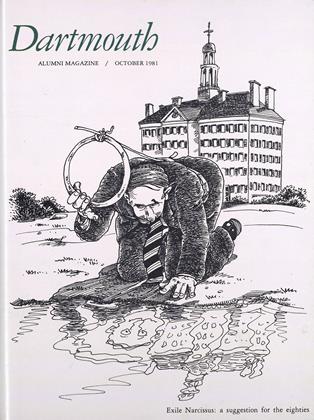

Cover StoryJust a suggestion, Mr. President: an agenda for the eighties

October 1981 -

Feature

FeatureCarlos Fuentes: Of isolation, of connection

October 1981 -

Feature

FeatureSubmariner

October 1981 By M. B. R -

Article

ArticleDeaths

October 1981 -

Article

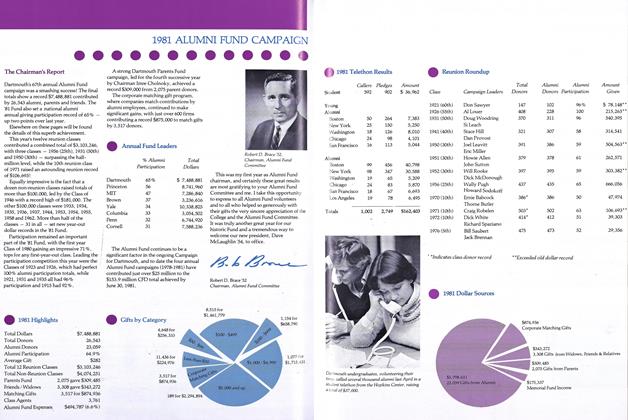

Article1981 ALUMNI FUND CAMPAIGN

October 1981 -

Article

ArticleWearers of the Green

October 1981 By Nancy Wasserman '77

Peter Smith

-

Article

ArticleFilm Director

FEBRUARY 1970 By PETER SMITH -

Article

ArticleIn the Wide, Wide World

MAY 1982 By Peter Smith -

Article

ArticleAlms for Blissful Calm

SEPTEMBER 1982 By Peter Smith -

Books

BooksAll Biology Is Indebted . . .

November 1983 By Peter Smith -

Books

BooksWords of Wisdom

MAY 1984 By Peter Smith -

Books

Books"One Man in His Time..."

JUNE/JULY 1984 By Peter Smith

Article

-

Article

ArticleE. W. Knight, '87 Nominated

DECEMBER 1929 -

Article

ArticleFitts Scholarship Fund

FEBRUARY 1963 -

Article

ArticleDanube Canoers Play Host To Iron Curtain Students

OCTOBER 1965 -

Article

ArticleFinding His Way

Jan/Feb 2005 By Kathryn McKay -

Article

ArticleHARRY L. HILLMAN

October 1945 By SIDNEY C HAZELTON '09 -

Article

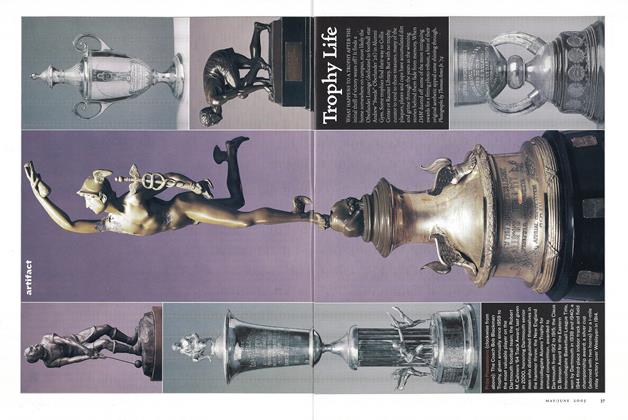

ArticleTrophy Life

May/June 2005 By Thomas Ames Jr., '74