SINCE coming to Dartmouth two years ago, Don C. has torn cartilage in his knee and sprained his left ankle twice. Disabling as these injuries have been, even more damaging have been injuries to his self-esteem. The son of a doctor and a stellar student in high school, Don came to college heavily invested in the idea of himself as a future physician. He was not prepared for the possibility of getting anything other than As in his pre-med courses, and he looks upon the Bs and few Cs he has pulled in at Dartmouth as if they were Fs. What's more, Don views his less than top- notch grades not as indices of his perform- ance in specific courses but as reflections of his entire human worth. All in all, Don feels like a failure. He also feels scared, vulnerable, and sometimes angry, though at precisely what he couldn't say. Don is reluc- tant to admit or confront these feelings. If only I work harder, he tells himself, I can still make it into medical school; then everything will be all right.

During the week, Don spends all his free time studying. He has given up the athletic activities that once gave him so much pleasure, claiming his knee and ankle can't take the strain. On those occasional weekends when he allows himself time off from studying, Don goes partying. When he parties, he gets drunk, extremely drunk, and when he gets drunk he also gets mean.

Down a flight of stairs in Don's dorm lives Debbie A. She, too, is a junior, and she, too, is in trouble. During her freshman year, she felt she did not "fit in" at Dartmouth, and she sought consolation in food, gaining about 20 pounds in the process. Through scrupulous dieting, Debbie has since lost those 20 pounds and more; she is now seriously underweight, in fact. Nonetheless, Debbie still lives in dread of being fat, and she thinks about food constantly; sometimes she even dreams about it.

Like Don, Debbie studies hard; it is a good way, she figures, to keep her mind off food. She also works her body hard, running as many as 15 miles a day and often topping off this exertion with long bike rides and hikes. On her "good" days, she is careful to consume no more than 600 calories. But periodically Debbie goes on food binges, devouring, usually late at night and always in solitude, several thousand calories worth of junk food in one sitting. After these "pig-outs," Debbie goes into the bathroom, sticks her finger down her throat, and gags until she vomits.

Neither Don nor Debbie is much interested in establishing an intimate sexual relationship. Both have been in love during their years at Dartmouth, and both got burned. Sex makes life messy and complicated, and intimacy with another human being isn't worth the hurt it inevitably, both believe, will bring. Besides, neither has the time.

DON C. AND DEBBIE A.are not real students, but their problems and their ways of handling them or, rather, not handling them . are real enough, and not all that uncommon on today's college campuses. Don and Debbie are what mental health professionals would call "obsessivecompulsives," people who are preoccupied with one aspect of life whether it be "making it" or being thin to the exclusion of other interests, and whose behavior is made unbalanced, even bizarre, by their myopic concern with.one particular goal. Characteristic of obsessive-compulsives is "all-or-nothing" thinking, thinking that allows for no middle ground: either I got an A or I failed; either I am perfect or a total mess; either I am always in control or always out of control. Common, too, are "if-then" scenarios: if only I work hard, I will succeed; if only I get into medical school, I will be happy; if only my body conforms to certain standards, the rest of my life will fall in line. When the conditions set by these "ifs" are not met, the controlling script by which the obsessivecompulsive lives promises, if not doom, at least misery.

Classic Freudian theory holds that obsessive-compulsives come into being because of an anal fixation established in early childhood; such persons were pushed on the potty too soon, too hard, or something like that. Now, however, many dispute this theory. Among those who would dispute it are the staff members of Dartmouth's Counseling-Mental Health Services. They are generally agreed that, as staff psychiatrist Henry Payson put it recently, "people can be trained to be obsessional later in life." Moreover, they are agreed that a place like Dartmouth, with its high performance standards and "pressure-cooker" atmosphere, constitutes a perfect training ground for obsessional thinking and compulsive behavior. Said Payson: "It used to be assumed that in order to be a good obsessional you had to have a problem with the pot early on. But I'm convinced that many [previously non-obsessional] people have come out of Dartmouth and are coming out obsessional, focused, rigid . . . unable to show interest in and derive joy out of a wide range of activity. I think it's possible for people to come to Dartmouth without these kinds of problems, and for this environment to neuroticize them so that they become disabled."

DARTMOUTH'S Counseling-Mental Health Services, located on the second floor of Dick's House, operate under the auspices of the College Health Service. Six counselors with varied training comprise the staff and provide Dartmouth undergraduate and graduate students with such services as crisis consultation, short-term individual psychotherapy, couples counseling, and group counseling. The staff director is Francis W. "Bud" King, an affable man who has been at Dartmouth so long and in such a capacity that he probably knows the school far better than most who spent a mere four years here. King, a clinical psychologist, came to Dart- mouth in 1949, at which time he joined what was then the Department of Psychology's guidance center. Later this became Mental Health Services, which, still later, in 1971, merged with the counseling services in College Hall to become Counseling-Mental Health Services.

"When I was in school," said a member of the class of 1961, "I didn't know anyone who went for mental health help. Or maybe it was that people were going but just didn't talk about it." Students today still may not talk about it, but apparently they are going. Last year, the total number of outpatient visits to Counseling-Mental Health Services was 3,867, up from 2,991 the previous year. Because most students who seek counseling go for several visits and tabs are kept on visits, not heads, King said he has no idea how many individuals are represented by these figures. But in a recent term alone, he reported, his staff saw 250 individual students.

Although the outpatient visit statistics show an increasing use of counseling services over the years, King is hesitant to view the statistics as indicative of any marked trend. "We don't have the numbers, so I couldn't tell you how many more students are coming in now than ten or fifteen years ago," he said. "Without any hard evidence, I'd say there's been a shift upwards in the past few years, but it's probably a slight shift."

Among certain groups of Dartmouth students, however, there definitely has been an upsurge. "Business school and medical students we're seeing more of them," King said. The same is true of Arts and Sciences graduate students, whom King called Dartmouth's "lost souls." Arriving on a campus geared toward undergraduates, Ph.D. students have "a rough time," King observed. "After a while they find a niche within their departments, but the first year or two they don't belong to anyone, they live God knows whereji they don't eat at Thayer, they have no graduate center . . . they're really lost."

Non-white students use the counseling services only rarely, if at all, which is in keeping with nationwide trends. Nationally, staff counselor Beverly Smith pointed out, "Minorities don't use mental health services." Also consistent with national practice, Dartmouth women use mental health services, and all health services, more than Dartmouth men. In fact, if any one development has helped to push up the total of visits to Counseling-Mental Health Services in recent years, that development is coeducation. Last year, slightly more than half of outpatient visits were made by women, even though women made up only about a third of the enrollment. For every 100 males at Dartmouth in 1980-81, King reported, there were 70 male visits to the second floor of Dick's House; for every 100 females, there were 179 female visits. Put simply, women at Dartmouth use the Counseling-Mental Health Services more than two and a half times as often as Dartmouth men.

WHAT is it that most often brings a student to King and his staff for help? Rarely is it what laypersons would characterize as outright lunacy. "Sure," King remarked, "once in a while we get some real sickies, but that's to be expected when you're dealing with a population of 3,000 to 4,000. I don't care who picks em A1 Quirk or whoever when you've got this large a number, you're bound to get some weird and strange people."

Occasional weirdness aside, King said that "the most common kind of thing we've seen aver the years is people feeling blue and depressed and anxious." For many, he continued, "this is the first time they've been in this fast a pool," and it's the first time they've found themselves sinking into depression and self-doubt. For others, explained Smith, "It's not the first time they've had this kind of feelings. They've had these feelings before, but this is the first time they felt they needed outside help, or had the freedom and opportunity to seek it."

Is there a stigma attached to visiting Counseling-Mental Health Services? Although King said that "some people are very uncomfortable about coming here and some really don't give a damn," he and his staff agree that many students feel uneasy about getting psychological help. A principal reason for this, counselor Bruce Baker believes, is simply that "there's a big risk in opening up to another person." Payson concurs, adding that there's also a large risk in being honest with one's own self. "The most common defense against a problem is denial," he explained. "Once you finally open up and see a problem in all its ghastly dimensions, the person's self-image takes a serious blow."

Another reason some students may feel uneasy about getting psychological counseling is the fear of appearing deficient or odd in the eyes of their peers. Such a fear is especially understandable at Dartmouth, where, according to King and his colleagues, if male students are frequently branded "wimps" and "sissies," female students are often derided for being "too sensitive" or "overly emotional." Hence, King says, "a lot of students come in saying they have academic problems, not emotional ones. An academic problem is an excellent ticket of admission. It's a lot easier to come in saying you're having trouble writing papers or studying than to come in saying you're shy or scared or lonely."

Noting that "I can't study" is a fairly common gambit, King said that in some cases the problem is simply what the student says it is that he or she can't study. More often than not, however, the inability to study is symptomatic of a deeper and more complicated problem, one that the student may not really want to confront. "A pretty typical case," King explained, "is a kid who comes in here saying he's having a hell of a time with Bio 5 and organic chemistry. So why, you ask him, is he taking all these premed courses, and it turns out that his father is a doctor, and so was his grandfather, and that all his life this kid was supposed to be a doctor even though he might not really be cut out for it. Then you talk to him some more and you find out that not only is the father a doctor, he's also a son of a bitch, and the son really doesn't want to emulate his father, he wants to murder him." Some- what rhetorically, King asked, "So what do we call this? Is this an academic problem like the student says, or is it a family problem?"

REGARDLESS of what specific complaint brings a student to Counseling-Mental Health Services in the first place, the staff there said that underlying most problems is one thing: conflict. The conflict may be between the student and his or her parents; between lovers, spouses, or roommates; between the student's future goals and actual aptitudes; between the student's own values and the values of the College or the larger world; or between two opposing parts of the student's self. Whatever the presenting problem may be, though, behind it is usually some sort of conflict that needs confrontation and resolution. At least in part, it is the desire to avoid, eliminate, or deny the existence of conflict that causes students like Don C. and Debbie A. to act the way they do.

The type of behavior evinced by Don C. and Debbie A. and other students may not make them happy, but at a place like Dartmouth it may make sense. "A lot of obsessional behavior is functional," King pointed out. "Some medical students, for example, wouldn't survive without being somewhat obsessional." The same applies to many undergraduates, more and more of whom are competing for admission into professional schools, and all of whom seem aware that in a shrinking economy jobs are tight. "Dartmouth hasn't developed a trade-school mentality yet," said King, "but it's getting close. Students are increasingly heading toward a narrow range of professions and are more likely to see one another as competitors." In such an atmosphere, observed counselor Diane Kilpatrick, perfectionist standards are the norm, and "there is a lot of fear and a tremendous pressure to perform." There is also, added Payson, "a tendency to lose perspective and focus exclusively on where you stand on the totem pole." Given all this, the members of the Counseling-Mental Health staff agree that many students feel they have no choice but to become single-minded and obsessional in pursuit of their goals.

Even when it does not help in reaching a goal, obsessional behavior can make sense. Don C., for example, probably won't get into medical school no matter how hard he tries. Yet as long as he keeps telling himself that he can get in if only he works harder, he doesn't have to face the fact that his chosen career is inappropriate. This, in turn, enables him to avoid the dread question of what his other options are, and it also enables him to steer clear of conflict with his parents. "The disappointment and confusion of a student who finds that he's not cut out for the field he was supposed to go into can be devastating," King said. "If you decide in your junior year of high school that you're going to study medicine, it answers so many questions; it allows you to predict exactly what you'll be doing for the next 15 years of your life. And if you decide you're going to go into medicine or law or business, you get so many brownie points from the older generation. If you say you want to leave an honorable and respected field to study something weird like philosophy instead, all the relatives will wonder what's wrong with you."

Having a particular focus can greatly simplify present-day dilemmas, too. "The number and types of decisions students have to make are in many cases extremely troubling and overwhelming," said Kilpatrick. For many, the dilemma of deciding who one is and what one wants to do "is exacerbated by all the other decisions that have to be made: 'Do I go to Thayer at 5:30 or wait until my friends get out of lab? Do I run at 6:00 or run at 4:00?' For some, all these decisions, become terribly important and difficult to make." While some students end up not being able to make any decisions, Kilpatrick said that others find the answer in narrowing their interests and becoming extremely rigid."

Perhaps one of the most attractive aspects of having an obsession, even an inappropriate one, is that it can provide a student with the illusion of enormous control over his or her life. By telling himself that "if only I get into medical school, everything will be fine," a student like Don C. protects himself from the awful knowledge that maybe happiness is not synonomous with professional success, nor so easily achieved. "I often hear students say, 'lf only, then I'll be happy,' " remarked Kilpatrick. "If only they knew it wasn't so simple!"

INSIDE a stall in a women's bathroom on campus someone has written, "What does Dartmouth need more than wisdom?" In reply, and in a bold hand, someone else has penned, "GOOD SEX!" In the same stall a few months ago, another woman wrote: "I starve myself then I gorge myself on garbage and make myself throw up after- wards. I am getting out of control and am really disgusted with myself. Does anyone else have this problem?" In response, several others scrawled, "YES! YES! YES!"

If coeducation has prompted an increase in the number of visits to CounselingMental Health Services, there is ample cause. The changes wrought by the women's movement notwithstanding, King and his staff agree that "women's lives are still much more constricted than men's; women have fewer options and more conflicts." Citing the "Superwoman syndrome," Smith said that "a significant number of women here are going into traditionally male professions, and this puts them into competition and conflict with one another, with their male peers, with society, and often with themselves."

Not only do women have more conflicts, Kilpatrick said, they are also more pained by them than men. Referring to a study done in the early 19705, she-recalled that college men and women were asked about career and family goals. The men reported that they wanted their wives to have careers, and considered those careers as important as their own, but they also said they expected their wives to stay home and take care of the kids. "The men saw no contradiction, no conflict here," Kilpatrick said. "But the women certainly did." Among the first-year medical students she sees, Kilpatrick finds that women are constantly asking how other women have managed to work out conflicts between career and family. "Women are seriously asking these questions in the first year," she said. "But you don't hear these kinds of questions from guys."

Like some men, some women reduce the amount of conflicts in their lives by focusing exclusively on one particular goal being a star athlete, for example, or getting into graduate school. Far more often than men do, however, women also focus on food, becoming obsessed with being thin as if it were life's most important task. Since the advent of coeducation, two problems the staff at Counseling-Mental Health Services have become increasingly familiar with are anorexia nervosa, whose mostly female victims starve themselves, and bulimia, which is what afflicts Debbie A. As one of the women Kilpatrick sees has put it, such students have "a feast or famine approach to life."

Although she pointed out that "in our culture there's so much more emphasis on physical attractiveness in women than in men," Kilpatrick said she doesn't believe there's any one or simple explanation for the eating disorders she finds among female students. If there is a key in some cases, however, it may be in the process of what Payson calls "selective inattention." When people become obsessed with one aspect of life or one particular goal, such as being thin, he explained, "What is often most important is not what they're focusing on, but what that focus enables them not to look at or deal with." To illustrate Payson's point, Kilpatrick referred to a student who, in describing her fanatical efforts to remain thin, remarked that "I don't want another human being complicating my life." In this case, Kilpatrick said, "I think this may be the bottom line."

Women are not alone in dreading complications arising from closeness with others. Although, as Bruce Baker remarked, "students have a tremendous need for an intimate relationship at this time of their lives," he and his colleagues report that many also have a great fear. "Some students today feel very comfortable saying, 'Hi, how are you? You wanna go to bed?' " King said. "But there are still a lot of guys who are very shy, awkward, and left-footed as far as girls go, and a lot of girls who are the same way about guys." Moreover, when the counselors ask students whether they have a boy friend or girl friend, a common response is, "A boy friend or girl friend? I don't have the time."

WHEN students visit the first floor of Dick's House complaining of a cold or stomach upset, they get looked at by authoritative types in white coats, prodded and poked with instruments, told what it is that is ailing them, and then are usually told what they need to do and to take in order to get well. On the second floor of Dick's House, students find no white coats, no shiay instruments or fancy machines, no prompt and definite diagnoses, and no promises that if you do this and that and take this medication you'll feel better. "What do we actually do here?" King asked, laughing. "Well, if a student Comes in here feeling blue we haul oul the hydraulic jacks and lift his depression." Then, taking the question more seriously, he admitted, "We don't walk on water. We don't perform any miracles or come up with cures. What we basically do is talk."

The talking is done either on a one-toone basis or in groups. Mental-Health Counseling Services provide individual counseling, in most cases for four to six visits, and also conducts groups concerned with sexual problems and eating disorders. Then, too, there are "personal growth groups," in which, according to King, "people learn to relate and socialize and grow." For example, a student who is having trouble overcoming shyness, or being assertive, or handling anger may find a group of peers helpful. "In the groups, students have all the other kids hammering at them and supporting them," King explained. "They give one another the strength and courage to find out what's bothering them, and also the chance to try different behaviors. If you've always wanted to tell some guy he's a pain in the neck but are afraid of doing it, you can try it out in a group."

Whether problems are discussed in group settings or on a one-to-one basis, King said, the first task is exploration. "Usually, when someone comes in here he has a big chunk of his problem buried," King said. "The guy who is having trouble in classes may not really want to go to medical school, or maybe he doesn't even want to be in college. But he's buried this because he feels naughty about.going against daddy."

While both parties in a one-to-one counseling situation talk, what the counselor says is the less important part of the conversation. "In the traditional doctorpatient relationship," King explained, "the patient goes in and says this hurts, the doctor diagnoses and then says, 'Here, take these.' But here there's almost a complete flip-over of this relationship. We're here as a resource. When you go to a doctor, the important thing is his being able to figure out what's wrong. When someone comes to us, the important thing is not our understanding, it's the person's own realizations that are key. We can lay out on the table all that we think is going on, but unless the student can figure it out for himself, our understanding does no good."

Once a problem has been identified, the next step is toward change, if that's what the student wants. Sometimes what needs to be changed is very simple and becomes clear in the first session. "A simple case," King said, "would be a kid who is having trouble sleeping, and in talking to him you find out that he lives his whole life in bed. He studies in bed, eats in bed, entertains in bed, watches TV in bed. . . . What we'd do in this kind of situation is introduce some environmental changes, get the kid to exercise some discrimination about where he spends his time. If he uses his bed only for sleeping, he may find he no longer has trouble with it."

Other problems may be less easy to resolve. A student who is obsessed with getting into professional school, for example, may be able to identify the problems underlying his obsession but still may feel he doesn't have the option of drastically altering his life's course. After all, he does have to do something in life, and he doesn't want to be poor. Similarly, students with eating disorders like bulimia may have an extremely rough time kicking the feast-famine syndrome. "These eating disorders can be very bitchy and complicated," King said, admitting that the mental health profession remains mystified by them. "Anorexia," he added, "a lot of times ends in hospitalization."

To King, the most crucial stage of the therapeutic process is that which commences once formal counseling is over. "People do their own therapy," he said. "Much of it goes on outside the consulting room. Coming here may give a student a head start, but the real changes occur out there."

NONE of the problems that take students to the second floor of Dick's House is unique to Dartmouth; they can be found at almost any school, particularly the more elite and competitive ones. "I don't think there is a Dartmouth syndrome," King said from the perspective of three decades on campus. "The main difference between Dartmouth and Harvard or Columbia or wherever is that there you can put some change in a box and escape. You just hop on the subway. Before you're through the turnstile, you're in another world."

Yet, due to the Dartmouth Plan and myriad off-campus programs, Dartmouth students are frequently scattered all over the world, and this may exacerbate certain problems. "In normal life, you don't change your life drastically every ten weeks the way students here do," said one counselor. "I don't, want to say anything bad about the Dartmouth Plan, but change can be stressful and here there is constant change."

Other sorts of change, too, have apparently created special stresses for at least some students at Dartmouth. "In the fall of 1971," recalled King, "I saw a guy I'll never forget. He came in here saying he was feeling miserable and depressed and couldn't study. 'How long have you been feeling this way?' I asked him. I always ask that it's a standard question and always I get a standard vague reply. But not from this guy. He said he had been feeling this way since '6:31 p.m. on Sunday, November 21.' Well, when I heard that, I sat up in my chair and said, 'Jesus, what "happened then?' He looked at me and said, 'That's when Dartmouth announced it was going coed.' He felt he had had an implicit contract with Dartmouth,, and that it had been violated. He was crushed." '

Mary Ellen Donovan '76 has written aboutpornography and truckstops for the ALUMNI MAGAZINE.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureAmerica's First Hostage Negotiator

December 1981 By Peter Bridges -

Feature

FeatureFirst Five Months

December 1981 By Shelby Grantham -

Feature

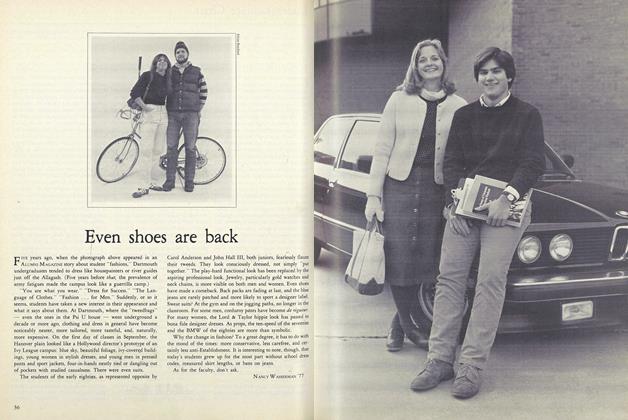

FeatureEven Shoes Are Back

December 1981 By Nancy Wasserman '77 -

Article

ArticleA Skeptic in Simian Clothing

December 1981 By Rob Eshman '82 -

Sports

SportsAn Unexpected Pleasure

December 1981 By Brad Hills '65 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1932

December 1981 By Adrian A. Walser

Mary Ellen Donovan

-

Feature

FeatureThe Lady and the Truckers

October 1978 By Mary Ellen Donovan -

Feature

FeaturePornography in Our Time

October 1980 By Mary Ellen Donovan -

Cover Story

Cover StoryPicking books Classic title, quirky tastes

MARCH 1982 By Mary Ellen Donovan -

Feature

FeatureWHY STUDY WOMEN?

OCTOBER 1982 By Mary Ellen Donovan -

Feature

FeatureOn Building Community

DECEMBER 1982 By Mary Ellen Donovan

Features

-

Feature

Feature5. Residential Life

December 1987 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryA Better Understanding

Mar/Apr 2007 By ANDREA USEEM ’95 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryHow to Find Your Inner Santa

Sept/Oct 2001 By ARTHUR H. RUGGLES JR. ’37 -

Feature

FeatureNew York Art Show Planned

JANUARY 1970 By H. ALLAN DINGWALL '42 -

Feature

FeatureWhen Dartmouth Had Its Own State (Almost)

May 1976 By JAMES L. FARLEY -

Feature

FeatureWhat's So New About It?

MAY 1973 By Joanna Sternick, A.M. '72