H.ONK! A loud horn goes off at a forest fire station in northern California, and out of a low green building pile four firefighters, an engineer, and a captain all in various states of undress. They leap onto two shiny red fire trucks and careen out of the station at top speed, sirens blaring and lights flashing. In the back of the truck the firefighters rapidly pull on yellow burn-resistant pants and shirts, leather gloves, and belts with canteens, emergency shelter, and hose clamps attached. They tie on damp bandannas "bank robber" style and listen to the twoway radio which reports the fire's location, size, and progress. As the truck rolls onto the scene, the firefighters jam on bright yellow hard-hats, adjust their goggles, and leap off the truck to grab hosepacks and begin the attack. . . .

Me? I'm the one with the black curls poking out from underneath my hard-hat struggling to keep my size extra-large pants up while I slip into a hosepack whose shoulder straps seem to have been designed for O. J. Simpson.

I decided to become a firefighter halfway through my first year at law school when I realized that a summer spent indoors in an office was just not for me. So I completed the required forms, physical fitness tests, and interview and learned in May that I had been hired as a California Department of Forestry seasonal firefighter stationed in Santa Rosa. As I was soon to discover, not many women are hired in this capacity in Sonoma County only eight out of 57 firefighters were women.

The following are excerpts from a journal I kept during my hitch as a C.D.F. "smokesucker":

Today we rose at 6:30 a.m. The six of us dressed quickly in our khaki- uniforms and piled out of the barracks to eat breakfast in the dining hall. (We do all our own cooking, dishwashing, and shopping during our five-day shifts.) Afterward we cleaned the barracks, readied our two trucks (1490 and 1477) for immediate departure, and began our daily physical training. PT" consists of a two-and-a-half-mile run on the station course, weight-lifting, and an alwaysrowdy game of basketball. The rest of the mornlng we all worked at various tasks: sharpening tools, cooking lunch, mowing lawns and I changed the oil on 1,477. The fire horn went off as we were sitting down to Brian's famous pizza. Abandoning lunch (a frequent occurrence), we raced outside to the trucks.

Our lucky day! We were the first trucks to arrive and the fire was still uncontained, mean- ing we had the "initial attack." Since the fire was rapidly climbing a steep hill, we would have to leave the trucks (our water source) at the bottom and do a "hose lay." A typical initial-attack hose lay entails running up a slippery hill with four or five other yellow-suited crazies-a 55pound hosepack on your back and a line of charged hose dragging behind you, while you roll out, clamp off, and couple 100-foot pieces of hose. While most of the crew is connecting the hose, one firefighter is at the nozzle extinguishing the flames ahead.

After the excitement of initial attack (not every truck on the scene always arrives in time to see flame) comes "mop-up" the slow, painstaking extinguishing of all "smokes," burning logs, and die-hard cowpies. Hours later, you're black, sweaty, and exhausted, and you're awarded a paper cup of cold water. Then you roll up all your dirty hose and go home to get more water, more gas, new hose, and new tools and to clean everything you've used so your truck is always ready. Then, you might get lunch. . . .

Being one of two women in an otherwise male crew had its interesting (and frustrating) moments. There are no "woman-sized" uniforms or equipment. (My emergency-gear belt always seemed to be hanging somewhere around my knees!) While most stations had segregated sleeping quarters for female firefighters, we, happily, were part of an "experiment" to see how women fit into the barracks situation. Finally, forestry terminology still lags uncomfortably behind reality. Terms like "nozzleman," "widow-maker," and "manpower" are common, although at Santa Rosa I did succeed in renaming the firefighter in charge of the nozzle a "nozzleperson!"

It was hard to shake the feeling that we were always "on stage," and that our individual accomplishments and mistakes were being generalized to all women.

That landmark day did arrive, however, when I felt I'd earned my hard-hat. It was on the "Big One," a 650-acre blaze that 300 firefighting personnel (297 men and three women) had been struggling to contain for three days. Three long days of little sleep, little food, and no washing had managed to reduce us all to a state of equality: tired and dirty. My crew worked a night shift cutting trail through heavy brush at the edge of the fire. It was hot, exhausting work and nobody seemed to care who that sootblackened firefighter next to them was as long as he or she was hacking out his or her share of the manzanita brush!

In short, prolonged coexistence proved to most that we were firefighters first and women second.

I must say I am proud of things I learned to do. I can now lube a truck; swing an axe; dress in full firefighting gear in 100 seconds; play a ferocious game of touch football; and wash, roll, pack, spaghetti, and couple (everything but eat) hose.

Worthwhile skills. Warm friendships. Fine adventures. And your very own hard-hat! What more could anyone ask from a job?

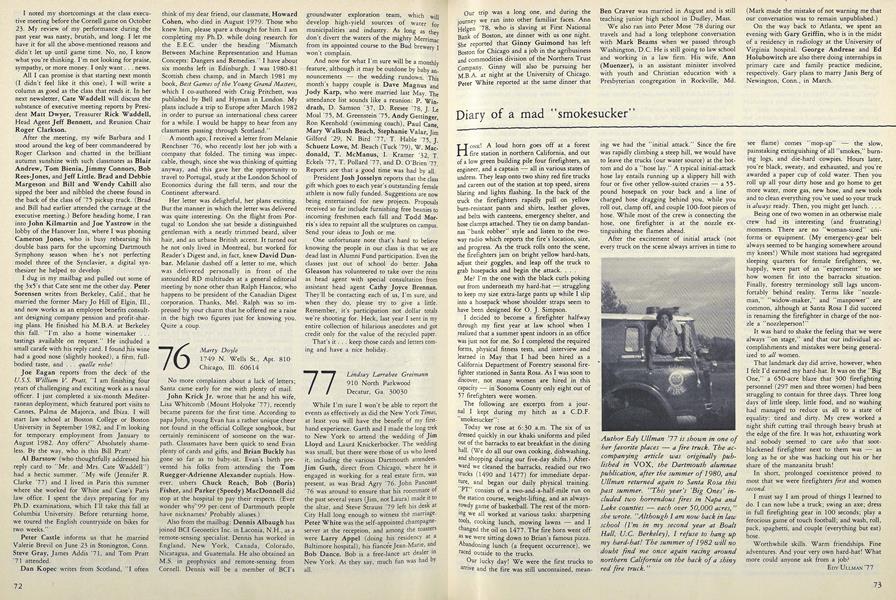

Author Edy Ullman 'll is shown in one ofher favorite places a fire truck. The accompanying article was originally published in VOX, the Dartmouth alumnaepublication, after the summer of 1980, andUllman returned again to Santa Rosa thispast summer. "This year's 'Big Ones' included two horrendous fires in Napa andLake counties - each over 50,000 acres, "she wrote. "Although lam now back in lawschool (I'm in my second year at BoaltHall, U.C. Berkeley), I refuse to hang upmy hard-hat! The summer of 1982 will nodoubt find me once again racing aroundnorthern California on the back of a shinyred fire truck."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureHard times in the pressure-cooker

December 1981 By Mary Ellen Donovan -

Feature

FeatureAmerica's First Hostage Negotiator

December 1981 By Peter Bridges -

Feature

FeatureFirst Five Months

December 1981 By Shelby Grantham -

Feature

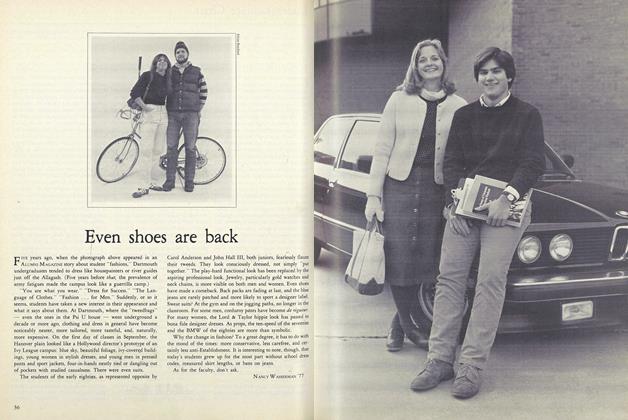

FeatureEven Shoes Are Back

December 1981 By Nancy Wasserman '77 -

Article

ArticleA Skeptic in Simian Clothing

December 1981 By Rob Eshman '82 -

Sports

SportsAn Unexpected Pleasure

December 1981 By Brad Hills '65