Armistice Day was chosen for a national Convocation on the Threat of Nuclear War, and the Tucker Foundation sponsored the local program. It opened with a noontime presentation on the Green of "Button, Button, Who's Got the Button?"

a mimed drama using a cast of hundreds, a'20-foot "nuclear weapon," two mammoth red push buttons, and an 18-foot string-and-tinfoil curtain of "fallout." After the final drumbeat, 800 gathered in Webster Hall for a discussion by a panel of doctors on the local impact of a nuclear war.

Ten minutes into the introduction by pediatrician Alan Rozycki '6l, a police officer mounted the stage, commandeered the microphone, and announced that a telephoned bomb threat necessitated the immediate evacuation of Webster Hall.The orderly withdrawal was punctuated by mutters of annoyance and comments about irony. The group reconvened in a hastily requisitioned auditorium in the Hopkins Center, and, with a little schedule-shuffling, the program continued.

Philip Morrison, Montgomery Fellow, bore on his stooped but able shoulders the burden of two appearances on the program a debate in the afternoon and the evening's lecture. Morrison, who participated in the atomic-bomb-producing Manhattan Project and worked at the Los Alamos Laboratories, is currently professor of physics at M.I.T. Regarded by many as the nation's foremost scientist opposing nuclear proliferation, Morrison took on Army Major Thomas Wheelock before a standing-room-only audience gathered to hear the two discuss both conventional and nuclear warfare under the title "Nuclear Weapons and National Security: More or Less?"

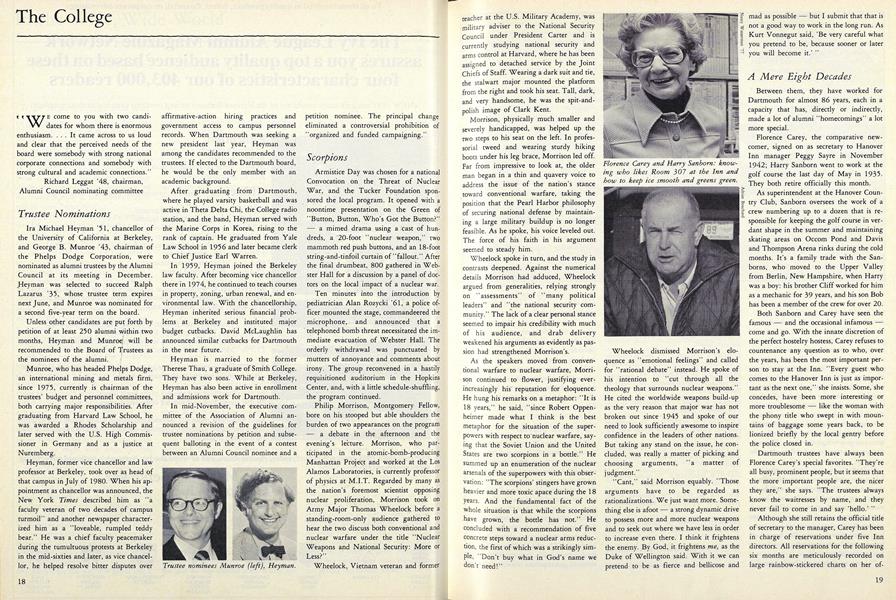

Wheelock, Vietnam veteran and former teacher at the U.S. Military Academy, was military adviser to the National Security Council under President Carter and is currently studying national security and arms control at Harvard, where he has been assigned to detached service by the Joint Chiefs of Staff. Wearing a dark suit and tie, the stalwart major mounted the platform from the right and took his seat. Tall, dark, and very handsome, he was the spit-andpolish image of Clark Kent.

Morrison, physically much smaller and severely handicapped, was helped up the two steps to his seat on the left. In professorial tweed and wearing sturdy hiking boots under his leg brace, Morrison led off. Far from impressive to look at, the older man began in a thin and quavery voice to address the issue of the nation's stance toward conventional warfare, taking the position that the Pearl Harbor philosophy of securing national defense by maintaining a large military buildup is no longer feasible. As he spoke, his voice leveled out. The force of his faith in his argument seemed to steady him.

Wheelock spoke in turn, and the study in contrasts deepened. Against the numerical details Morrison had adduced, Wheelock argued from generalities, relying strongly on "assessments" of "many political leaders" and "the national security community." The lack of a clear personal stance seemed to impair his credibility with much of his audience, and drab delivery weakened his arguments as evidently as passion had strengthened Morrison's.

As the speakers moved from convert tional warfare to nuclear warfare, Morrison continued to flower, justifying everincreasingly his' reputation for eloquence. He hung his remarks on a metaphor: "It is 18 years," he said, "since Robert Oppenheimer made what I think is the best metaphor for the situation of the superpowers with respect to'nuclear warfare, saying that the Soviet Union and the United States are two scorpions in a bottle." He summed up an enumeration of the nuclear arsenals of the superpowers with this observation: "The scorpions' stingers have grown heavier and more toxic apace during the 18 years. And the fundamental fact of the whole situation is that while the scorpions have grown, the bottle has not." He concluded with a recommendation of five concrete steps toward a nuclear arms reduction, the first of which was a strikingly simple, 'Don't buy what in God's name we don't need!"

Wheelock dismissed Morrison's elo- quence as "emotional feelings" and called for "rational debate" instead. He spoke of his intention to "cut through all the theology that surrounds nuclear weapons." He cited the worldwide weapons build-up as the very reason that major war has not broken out since 1945 and spoke of our need to look sufficiently awesome to inspire confidence in the leaders of other nations. But taking any stand on the issue, he concluded, was really a matter of picking and choosing arguments, "a matter of judgment."

"Cant," said Morrison equably. "Those arguments have to be regarded as rationalizations. We just want more. Something else is afoot a strong dynamic drive to possess more and more nuclear weapons and to seek out where we have less in order to increase even there. I think it frightens the enemy. By God, it frightens me, as the Duke of Wellington said. With it we can pretend to be as fierce and bellicose and mad as possible but I submit that that is not a good way to work in the long run. As Kurt Vonnegut said, 'Be very careful what you pretend to be, because sooner or later you will become it.'

Florence Carey and Harry Sanborn: knowing who likes Room 307 at the Inn andhow to keep ice smooth and greens green.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureHard times in the pressure-cooker

December 1981 By Mary Ellen Donovan -

Feature

FeatureAmerica's First Hostage Negotiator

December 1981 By Peter Bridges -

Feature

FeatureFirst Five Months

December 1981 By Shelby Grantham -

Feature

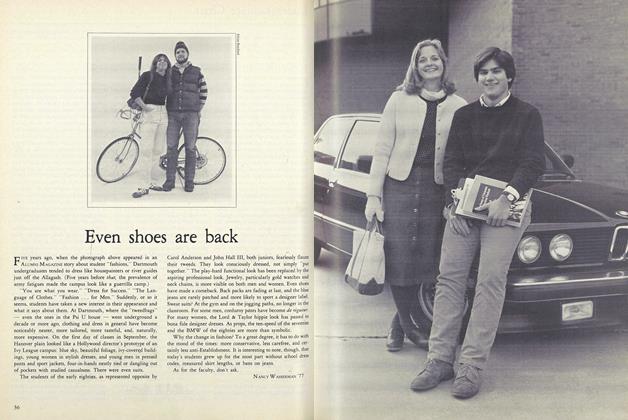

FeatureEven Shoes Are Back

December 1981 By Nancy Wasserman '77 -

Article

ArticleA Skeptic in Simian Clothing

December 1981 By Rob Eshman '82 -

Sports

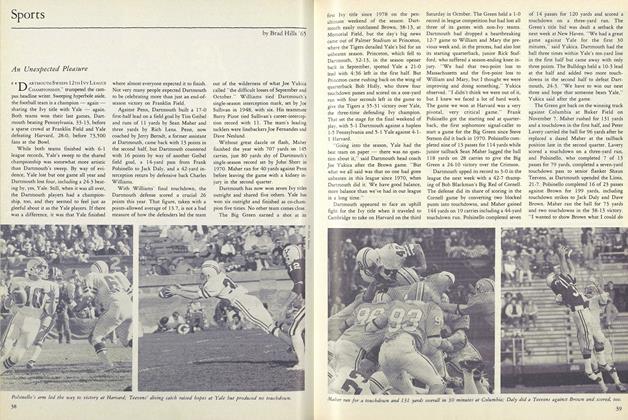

SportsAn Unexpected Pleasure

December 1981 By Brad Hills '65