I DREAMED about Peter last night. The funny thing is, I barely know him. But in my dream I was terribly upset. I was reading something he wrote a short story, I think and then I awoke, feeling anxious and empty. I don't remember what Peter's story was about, but it was very good. That was the problem. I had the same problem with John earlier that week, though this time I wasn't dreaming. One night, up late, we began a friendly bull session; we ended up playing the Comparison Game.

It's a strange game, requiring two players and four voices. The players talk back and forth in normal tones about their achievements and satisfactions. The other two voices are internal, each voice saying silently "I've done that," or "I should have done that," or "I've done something better than that." If John and Peter weren't such good people, all this comparing would be understandable. Adversaries must always measure themselves against their opponents. But the Comparison Game is something I play against even my closest friends. And I play it all the time, even in my dreams.

I've talked about the game to other students is it only my problem? No, they tell me, we all play the Comparison Game to one degree or another. "All through high school you're at the top'of your class," said one classmate, "then you come here and you start seeing what all these other students are doing. And it blows you right out of the box when you realize you're not the best."

"Your self-confidence starts to slip away," said another. "You lose perspective. You just think you don't do anything, so pretty soon you don't." When do you start comparing? Why do you start comparing? You just do."

The more precocious among us start in high school. We are raised learning the rules, the standards of evaluation made clear enough on applications to prep schools, summer internships, Dartmouth. The applications teach us what activities count, what experiences will make us more acceptable. Standardized tests such as SATs are but the iceberg's tip, beginners' stuff. We learn that an admission officer will more likely esteem the application boasting a Washington internship than one listing a summer job selling watermelons. I would happily abandon this assumption were I to read the following on a Dartmouth College admission form:

Below, please list all major awards and achievements received during the past three weeks. Use only the four pages provided. Remember: there is no right answer, and you are no less of a person for scooping ice-cream cones than for working for your senator, administering poultices to Masai warriors, or selling pork futures for Morgan Stanley. We're really just interested in the attitude with which you approach life and your ability to extract from every experience, whatever it may be, the joy, intrigue, drama, and humor which infuse each moment. Thank you.

No such entries exist. So the word has always been, and still is, that certain experiences are more useful, more practical, better. Certain lifestyles are more desirable. Even if we applicants try to break away from this attitude, even if we are in the process of learning to appreciate our own " lives and accomplishments, the residue from this training still stains our minds, teasing us to play the Comparison Game.

It's a no-win game. When I come home at 3:00 a.m. to find my roommate fast asleep, I regret not taking as good care of myself. When I'm in bed by 11:00 and my roommate returns at 4:00 a.m., I regret not working as late or as hard as he. In fact, in the very act of playing the Comparison Game, we lose. We are often unable to listen, understand, and share in our friends' joys and struggles when the "voice" is busily whispering, "Me too." Or, when the voice cries, "Why haven't I?" we turn our concentration from our achievements to our non-achievements, from qualities present to qualities lacking. From confidence to neurosis.

Once the Comparison Game begins, there is no end to it. Ask any senior to recite that litany of goals which require that we fulfill an institution's expectations of good personship: Rhodes, Reynolds, Stanford Biz, Harvard Med, corporate recruiters. Whether all these groups do in fact look on certain achievements, or amounts of achievements, as better than others, the belief that they do is by now ingrained. So, I must play the game again. I wonder, will I still play it at reunions, at parties, at informal meetings? With the person I marry? With my children? The pressures to play seem to get even stronger as one enters society from Dartmouth.

Before we realize it, the game has started anew. The measures by which we judge ourselves become intertwined, if not identical, with, say, Stanford Business School's or 1.8.M.'s standard of judging us. The gatekeepers of our careers become the molders of our selves.

If we actively question those standards, critically examine them before we chase after their attainment like puppies after tennis balls, then perhaps we can break the Comparison Game. It would no longer occur to us to measure our achievements against our friends' if we could discern what activities meant most to us as growing persons as well as hopeful applicants. Until I secure this security, I'll catch myself playing the Comparison Game from time to time. It almost happened yesterday. I went in to have my senior portrait taken, and an Aegis staff member handed me an "Activities Card" on which I was to list all ac-omplishments while at Dartmouth. My list will appear in the back of the yearbook with those of my classmates. As I turned in my card, I asked for another. The Aegis person looked up from her table, incredulous: "You need two?" "One's for future reference," I reassured her. I'm going to put that one on my wall. I'll pencil in my name up top. And across the face of the card I'll write, in three bold words, "That's good enough."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureHard times in the pressure-cooker

December 1981 By Mary Ellen Donovan -

Feature

FeatureAmerica's First Hostage Negotiator

December 1981 By Peter Bridges -

Feature

FeatureFirst Five Months

December 1981 By Shelby Grantham -

Feature

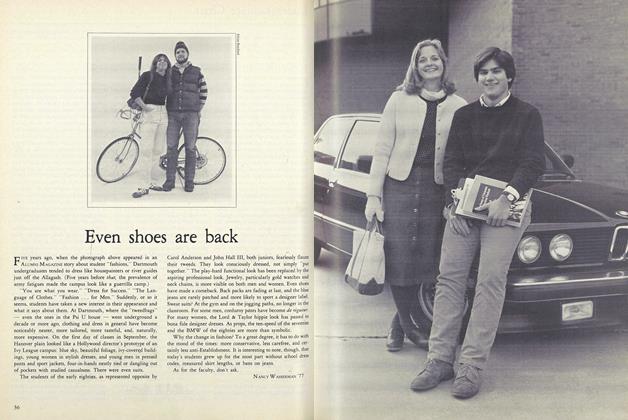

FeatureEven Shoes Are Back

December 1981 By Nancy Wasserman '77 -

Article

ArticleA Skeptic in Simian Clothing

December 1981 By Rob Eshman '82 -

Sports

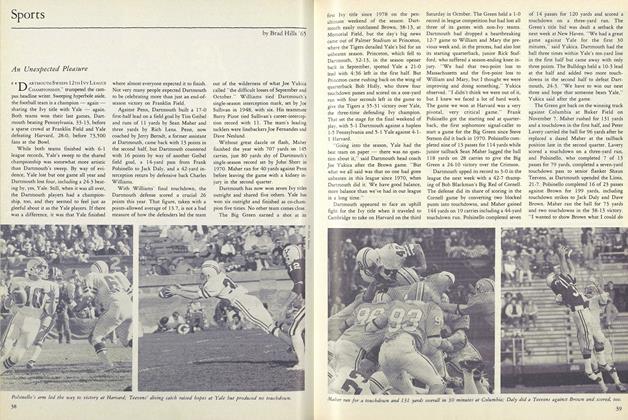

SportsAn Unexpected Pleasure

December 1981 By Brad Hills '65

Rob Eshman '82

-

Article

ArticleA Time Away

OCTOBER 1981 By Rob Eshman '82 -

Article

ArticleA Skeptic in Simian Clothing

DECEMBER 1981 By Rob Eshman '82 -

Article

ArticleBut Don't Talk About It?

MAY 1982 By Rob Eshman '82 -

Feature

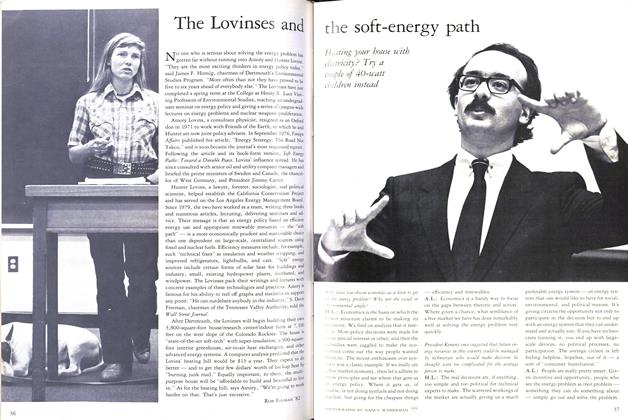

FeatureThe Lovinses and the Soft-Energy Path

JUNE 1982 By Rob Eshman '82 -

Feature

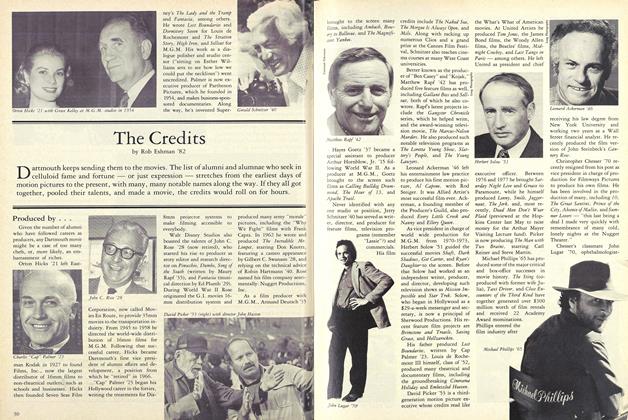

FeatureThe Credits

November 1982 By Rob Eshman '82 -

Feature

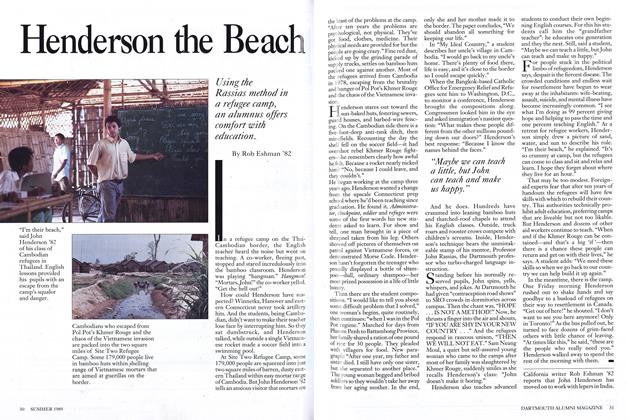

FeatureHenderson the Beach

June 1989 By Rob Eshman '82

Article

-

Article

ArticleFOUR PROMINENT LITERARY FIGURES TO ADDRESS ARTS

November, 1922 -

Article

ArticleFELLOWSHIPS ON GUGGENHEIM FOUNDATION AVAILABLE

April, 1925 -

Article

ArticleClocks Are His Hobby

March 1951 -

Article

ArticleAnother All American

MARCH 1992 -

Article

ArticleLaureled Sons of Dartmouth

October 1944 By H. F. W. -

Article

ArticleTurning on the Data Tap

NOVEMBER 1999 By Simone Swink '98