JON writes from Istanbul. Billy and Lisa send me letters from Israel. Emmy writes, "Hi from Hungary." I hear Lydia is in Wales. Hendo is in Albuquerque, Susi's in France, and Lynn may be in Alaska. Doug could be anywhere. And when you ask my parents where I've been during my absence from school, they'll roll their eyes and say, "Don't ask."

Can you blame them? After all, when they went to school, they went to school. To them, Language Study Abroad meant ordering lunch at the taco stand on Fifth and Hill. My parents, like most parents I know, can't exactly explain why their children so often trade the comfort of college life for the hazardous world beyond. Why, they ask, do our children give up days filled with rare intellects, leisure, and square meals for, say, shucking oysters in Eastpoint, Florida, at four dollars a gallon, two gallons a day?

Most parents use two theories to explain such behavior. The first holds that their children are briefly consumed by wanderlust and must travel to "get something out of their system." Travel, then, has all the importance of a good laxative. The other theory argues that students travel mainly to collect adventures, which they will pin into their memories like so many butterflies, to enjoy when life becomes drab.

I know for myself, and for most of my friends, these explanations are inadequate. They suggest that traveling is a transitory urge, of secondary importance in the student's life to the acquisition of diploma and job the real business of living.

When I left Dartmouth last fall, I felt I had gone bankrupt in the "real business of living." I could no longer remember why I attended school or what I hoped to gain from it. I soon realized there were aspects of myself that couldn't be nurtured in school. I needed to feel a part of the larger world, to know I am or could be useful to that world. But the isolation and egoism of college life my constant struggle to make the grade, my constant obsession with my future, my achievements had built a wall between me and what was happening outside Hanover. I had been too busy learning skills to contribute to society to learn firsthand just what that society is and what skills it needs. The way I could best begin to learn all this was to travel, to experience the world more immediately. I did not have to "get something out of my system"; I had to take something into it.

The hardest lesson is humility the painful process of learning the limits of my formal education. So often when faced with human dilemmas, I rummaged through my schooling and came up empty-handed. What speech class could have taught me how to convince a poor child in a Tennessee hollow that, even though his parents can't afford to buy him new clothes or running water for his bathing, it's still "worth it" for him to attend school? What history course could prepare me to ease the bitterness of the Vietnam vet whose friends stigmatized him as a killer when he returned home? I have learned a lot from Dartmouth, but there is much I haven't learned much I cannot learn until I accept experience as a teacher.

"We must go to people with our bodies," a 72-year-old Cincinnati preacher told me. Dartmouth has taught me invaluable skills to bring into the world, but until I learn to give of myself, to communicate with action as with words, to make myself vulnerable to a world more uncertain than academia, the wall between academia and the worldbeyond-the-Green will remain impenetrable.

There isn't room to share here all the other lessons learned by staying away from classrooms for a while. In the past 30 weeks, I've worked with many community groups around the country. I've also worked as a commercial fisherman, a watermelon vendor, a pepper-picker, a janitor, an oysterman, a baker on an off-shore oil rig, and a ranch-hand on a dairy farm. I've spent many weeks hitchhiking through the East and South. Of course, a roster of experiences doesn't guarantee a stream of insights. But contrary to theory, I won't file these experiences away to recall on some rainy day. They are not decorations to my diploma or, God knows, to a resume. They are experiences which have helped me begin to understand the world as no book could. And they were a lot of fun.

Fortunately, I have the opportunity for school and work and travel. At Dartmouth the three needn't be mutually exclusive. If I am to begin to understand this world wholly, to use my skills to meet its needs, I will always want to be able to travel and explore the world firsthand. Always. And I have a hunch that my friends would agree with me: Jon in Istanbul, Lisa in Israel, Susi in France, Emmy in Hungary, and Doug, who could be anywhere.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

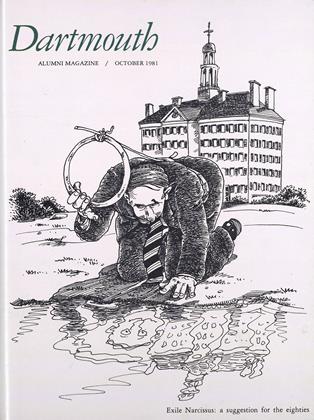

Cover StoryJust a suggestion, Mr. President: an agenda for the eighties

October 1981 -

Feature

FeatureCarlos Fuentes: Of isolation, of connection

October 1981 -

Feature

FeatureSubmariner

October 1981 By M. B. R -

Article

ArticleDeaths

October 1981 -

Article

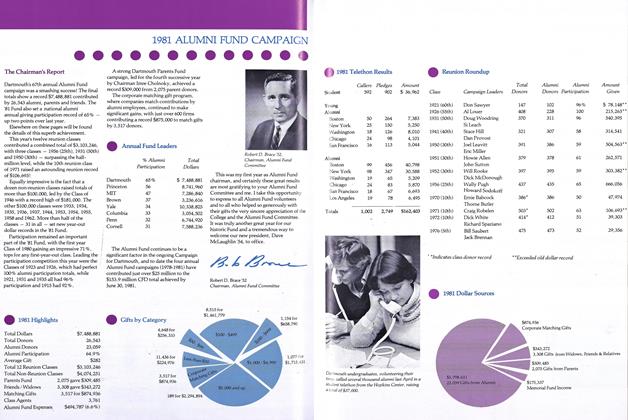

Article1981 ALUMNI FUND CAMPAIGN

October 1981 -

Article

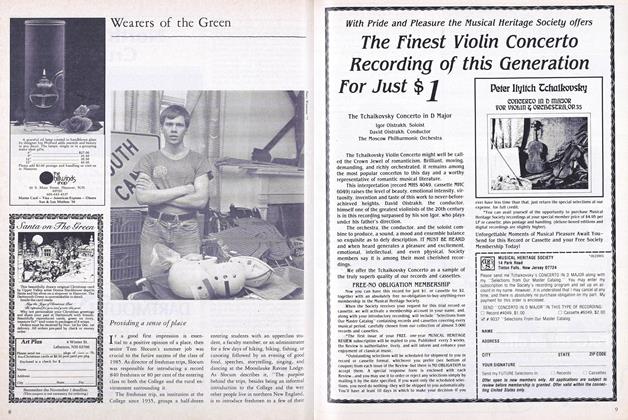

ArticleWearers of the Green

October 1981 By Nancy Wasserman '77

Rob Eshman '82

-

Article

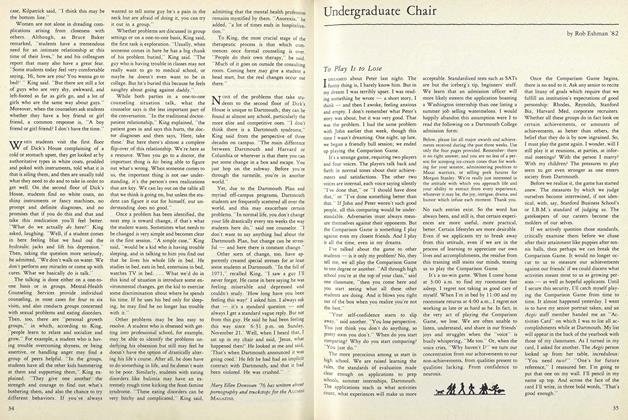

ArticleTo Play Is to Lose

DECEMBER 1981 By Rob Eshman '82 -

Article

ArticleBut Don't Talk About It?

MAY 1982 By Rob Eshman '82 -

Feature

FeatureThe Credits

November 1982 By Rob Eshman '82 -

Feature

FeatureHenderson the Beach

June 1989 By Rob Eshman '82 -

Feature

FeatureShrink Rap

NOVEMBER 1990 By Rob Eshman '82 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryThe Ascent of Korey

MARCH 1995 By Rob Eshman '82

Article

-

Article

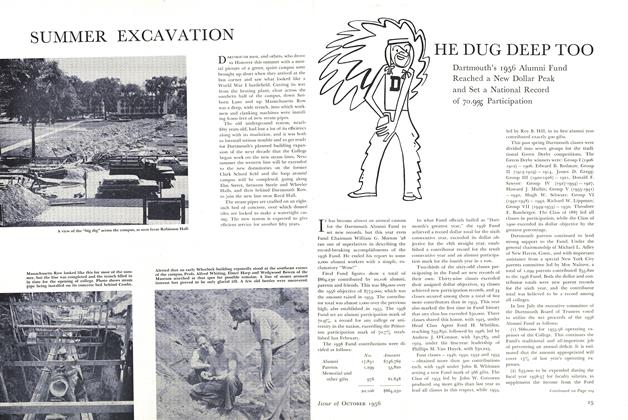

ArticleSUMMER EXCAVATION

October 1956 -

Article

Article"Animal House" In News Again

Sept/Oct 2006 By Carolyn Kylstra ’08 -

Article

ArticlePROFILE: Angela Rosenthal

Nov/Dec 2006 By Lauren Zeranski '02 -

Article

ArticleTrack

March 1960 By RAY BUCK '52 -

Article

ArticleProfessor Adams

October 1938 By Royal Case Nemiah -

Article

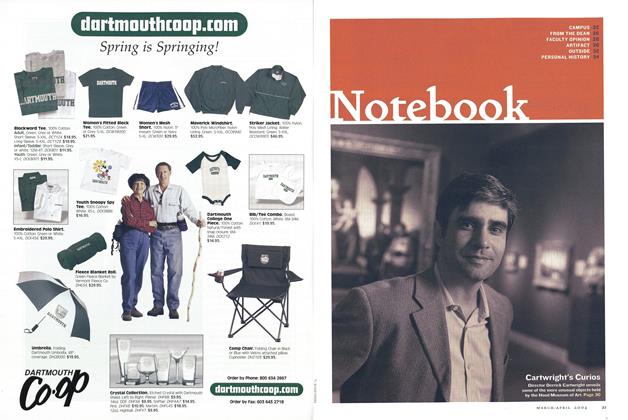

ArticleNotebook

Mar/Apr 2004 By THOMAS AMES JR. '74