Selling soul food in Jaiwan, a Dartmouth qrad is bullish on Chinese shopping. by Sheila Meloin

It IS NEARING DINNER TIME on a weekday afternoon and the sidewalk around "Uncle O'Yang's" Taipei street stall is packed with dozens of children clamoring to be served. There are plenty of less crowded stalls nearby at which they could buy such common street fare as tropical fruits, fried scallion cakes, deep-fried coagulated pig blood, and the local specialty, "stinky tofu." But Uncle O'Yang's is the only stall of its kind in Taipei and the kids prefer to wait.

"Large french fries and lemonade, Uncle O'Yang!" rise the shrill, excited voices.

"What's an apple fritter, Uncle O'Yang?"

Nonplused by the ceaseless racket, Uncle O'Yang calmly plunges a basket of frozen fries into a wok filled with sizzling oil, warns the kids to keep back, and then bends over the portable freezer to scoop out a cone. When the fries are done he dumps them into bags, passes them out, collects money, and makes change.

An old woman hobbling by stops and watches the scene with an astonished look on her face. "How strange," she mumbles to herself. "I've never seen anything like this before."

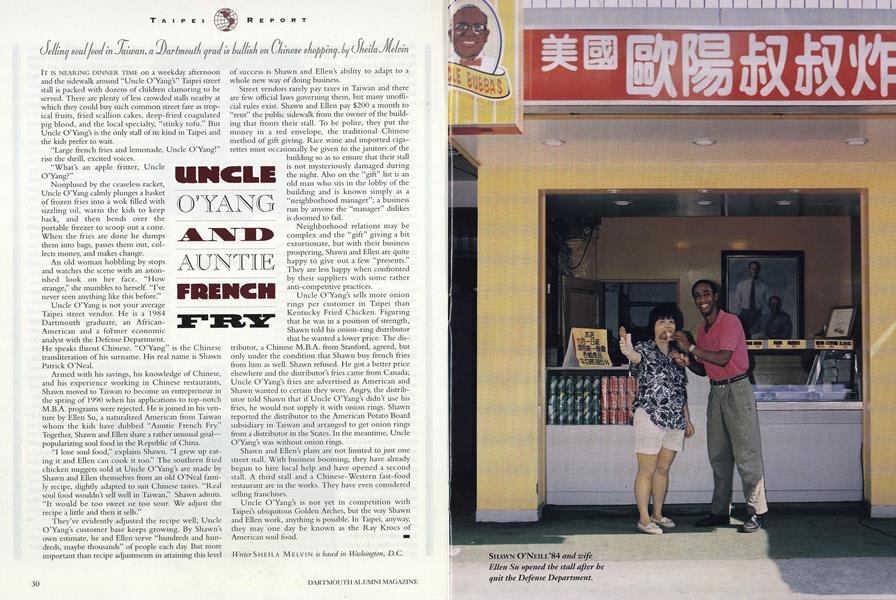

Uncle O'Yang is not your average Taipei street vendor. He is a 1984 Dartmouth graduate, an African- American and a former economic analyst with the Defense Department. He speaks fluent Chinese. "O'Yang" is the Chinese transliteration of his surname. His real name is Shawn Patrick O'Neal.

Armed with his savings, his knowledge of Chinese, and his experience working in Chinese restaurants, Shawn moved to Taiwan to become an entrepreneur in the spring of 1990 when his applications to top-notch M.B.A. programs were rejected. He is joined in his venture by Ellen Su, a naturalized American from Taiwan whom the kids have dubbed "Auntie French Fry." Together, Shawn and Ellen share a rather unusual goalpopularizing soul food in the Republic 01 China.

"I love soul food," explains Shawn. "I grew up eating it and Ellen can cook it too." The southern fried chicken nuggets sold at Uncle O'Yang's are made by Shawn and Ellen themselves from an old O'Neal family recipe, slightly adapted to suit Chinese tastes. "Real soul food wouldn't sell well in Taiwan," Shawn admits. "It would be too sweet or too sour. We adjust the recipe a little and then it sells."

They've evidently adjusted the recipe well; Uncle O'Yang's customer base keeps growing. By Shawn's own estimate, he and Ellen serve "hundreds and hundreds, maybe thousands" of people each day. But more important than recipe adjustments in attaining this level of success is Shawn and Ellen's ability to adapt to a whole new way of doing business.

Street vendors rarely pay taxes in Taiwan and there are few official laws governing them, but many unofficial rules exist. Shawn and Ellen pay $200 a month to "rent" the public sidewalk from, the owner of the building that fronts their stall. To be polite, they put the money in a red envelope, the traditional Chinese method of gift giving. Rice wine and imported cigarettes must occasionally be given to the janitors of the building so as to ensure that their stall is not mysteriously damaged during the night. Also on the "gift" list is an old man who sits in the lobby of the building and is known simply as a "neighborhood manager"; a business run by anyone the "manager" dislikes is doomed to fail.

Neighborhood relations may be complex and the "gift" giving a bit extortionate, but with their business prospering, Shawn and Ellen are quite happy to give out a few "presents." They are less happy when confronted by their suppliers with some rather anti-competitive practices.

Uncle O'Yang's sells more onion rings per customer in Taipei than Kentucky Fried Chicken. Figuring that he was in a position of strength, Shawn told his onion-ring distributor that he wanted a lower price. The distributor, a Chinese M.B.A. from Stanford, agreed, but only under the condition that Shawn buy french fries from him as well. Shawn refused. He got a better price elsewhere and the distributor's fries came from Canada; Uncle O'Yang's fries are advertised as American and Shawn wanted to certain they were. Angry, the distributor told Shawn that if Uncle O'Yang's didn't use his fries, he would not supply it with onion rings. Shawn reported the distributor to the American Potato Board subsidiary in Taiwan and arranged to get onion rings from a distributor in the States. In the meantime, Uncle O'Yang's was without onion rings.

Shawn and Ellen's plans are not limited to just one street stall. With business booming, they have already begun to hire local help and have opened a secondstall. A third stall and a Chinese-Western fast-food restaurant are in the works. They have even considered selling franchises.

Uncle O'Yang's is not yet in competition with Taipei's übiquitous Golden Arches, but the way Shawn and Ellen work, anything is possible. In Taipei, anyway, they may one day be known as the Ray Krocs of American soul food.

SHAWN O'Neill'84 and wifeEllen Su opened the stall after hequit the Defense Department.

Writer SHEILA MELVIN is based in Washington, D.C.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

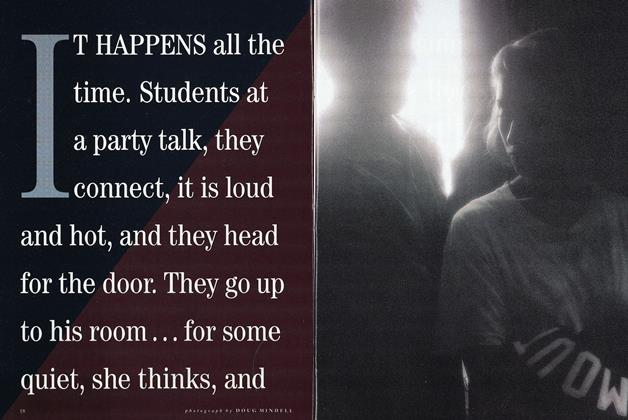

Cover StoryThen lings get ugly

November 1992 By Karen Endicott -

Feature

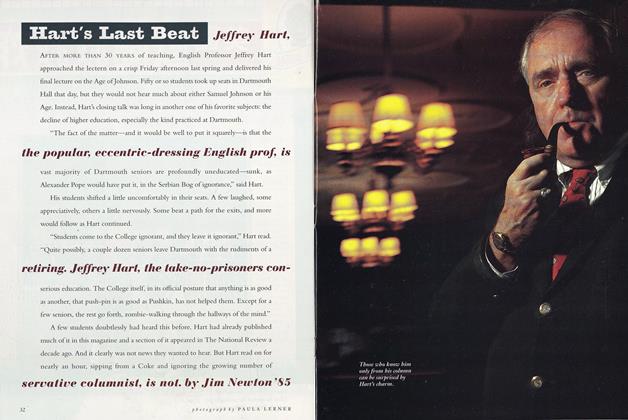

FeatureHart’s Last Beat

November 1992 By Jim Newton ’85 -

Article

ArticleIs Socialism Really Dead?

November 1992 By William L. Baldwin -

Article

ArticleDr. Wheelock's Journal

November 1992 By “E. Wheelock” -

Article

ArticleLessons of the Law

November 1992 By James O. Freedman -

Class Notes

Class Notes1985

November 1992 By Mark Stern

Features

-

Feature

FeatureOnward and Upward with '68

NOVEMBER 1964 -

Feature

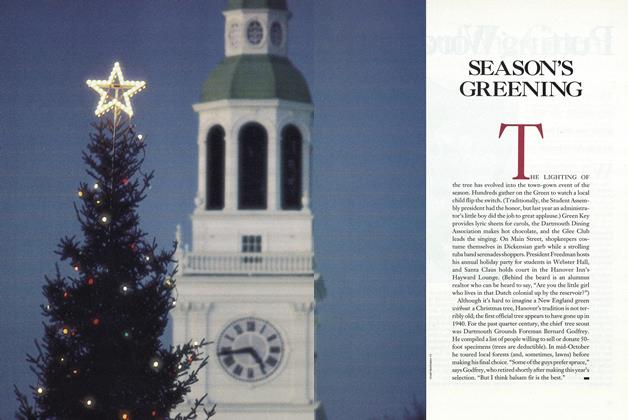

FeatureSEASON'S GREENING

December 1989 -

Feature

FeatureThe Senior Valedictory

JULY 1970 By CRAIG JOYCE '70 -

FEATURES

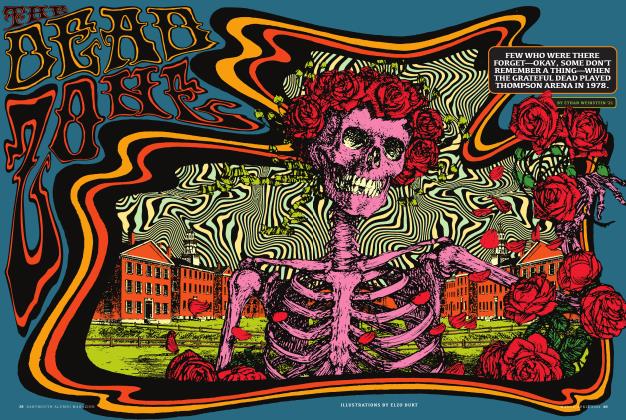

FEATURESThe Dead Zone

MARCH | APRIL 2022 By ETHAN WEINSTEIN '21 -

Feature

FeatureBelieve It or Not!

October 1974 By GREGORY C. SCHWARZ -

Feature

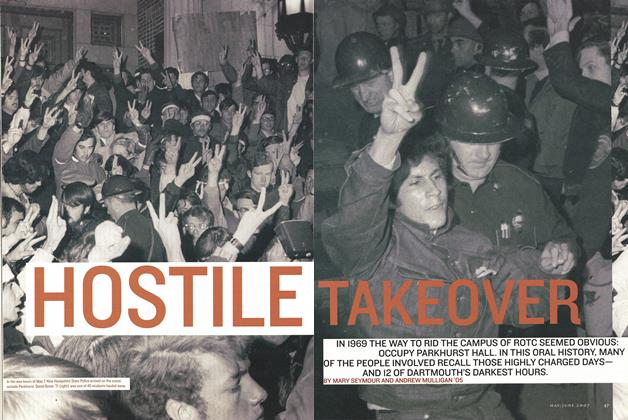

FeatureHostile Takeover

May/June 2007 By MARY SEYMOUR AND ANDREW MULLIGAN ’05