What do Raquel Welch, Mrs. Miniver, and the Seven Healthy Life Habits have in common? Sam Shekel Private Eye, Ear Nose, and Throat might refer that mystery to the Silver Fox a.k.a. Raymond F. DeVoe Jr. '5O. DeVoe, Shekel's literary sire and a newsletter writer for the securities firm Bruns, Nordeman, Rea, assembles these and other exotica in the process of advising readers about the stock market and the general investment climate.

DeVoe has embraced an odd perspective on Wall Street life and times. Take Raquel, for example. According to DeVoe, her dress reminds us to keep our eyes peeled for fleeting economic emergency signals. Otherwise, whap, we've missed what we came to see. A passage from Mrs. Miniver warns of the dangers of seeking the past in the future. And the healthy habits, according to Dr. Lewis Thomas, instruct us that conventional wisdom is appealing though often logically ambiguous: Does the lazy man become ill or does the ailing man succumb to indolence? Then there's Sam Shekel himself. He manages to review Adam Smith's pessimistic new book, Paper Money, and give us a more optimistic view of the economy while evoking the hard-boiled style of Chandler. He also advertises DeVoe's newest publication, Distant Early Warning, which recommends specific investments to its readers.

DeVoe has two justifications for his offbeat style. First, his conception of the market and the economy resembles less a scientifically-precise machine than a messy, emotion-laden, anthropomorphic creature. Indeed, DeVoe feels that the market, like man, is governed by "fear, apprehension, and greed." Investing, then, far from being a simple matter of plugging the right numbers into the right formula or anticipating an upturn in the economic cycle, requires the evaluation of a less tangible combination of the factors that effect the economy and, more exactly, people in the economy. The second justification is that DeVoe's way is more fun. After all, how many market strategists quip that "a penny saved is ridiculous" or write that "the last Administration left the economy in a God-awful mess, making the Augean Stables look like an overnight kittylitter box in comparison?"

One of DeVoe's favorite methods of analysis involves poking fun at all the figures that economists love to throw at one another. His Cost of Loving Index, a response to the more conventional Consumer Price Index, prices the inflation-ridden social practice of paying romantic court. Though the C.0.L., by DeVoe's measure, has risen 419 per cent since the fifties, the C.P.I, is up only 178 per cent. But, says DeVoe, he's been told by some of his younger friends that the modern gallant has dispensed with the corsage and the nights dancing and even the wedding he just invites the object of his not-so-attentive attentions for a night at his place. DeVoe's point is this: Economic statistics aren't always indicative of the economic reality. They are often based on out-of-date assumptions about the way people live and spend their money.

DeVoe's interest in how economics fits into the bigger picture of life goes back as far as his Dartmouth days. He recalls handing in a paper that compared the government's fiscal policy with a house thermometer. Unfortunately, the instructor didn't understand the workings of a thermostat and so couldn't appreciate the analogy. The readers of The DeVoe Report,Investment Implication, and Distant EarlyWarning, DeVoe presumes, have a more complete working knowledge of life and economics. They'd better if they hope to appreciate his eccentrically expressed financial insights. Failing that, readers can simply sit back and savor the wry sense of humor that pervades DeVoe's work. If asked which comes first, the fun or the profit, DeVoe waffles. Ask Sam Shekel.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureTelling Another's Tale

May 1981 By Gregory Rabassa -

Feature

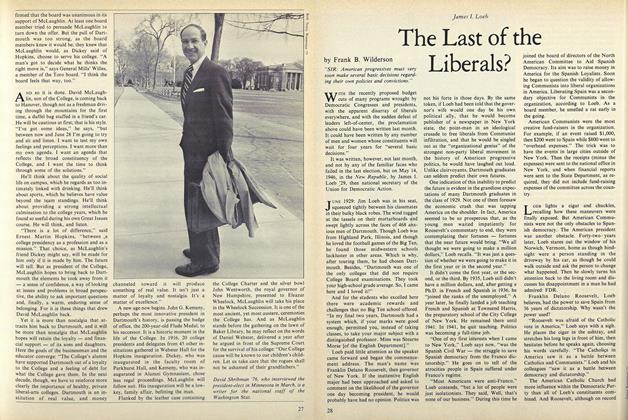

FeatureThe Last of the Liberals?

May 1981 By Frank B. Wilderson -

Feature

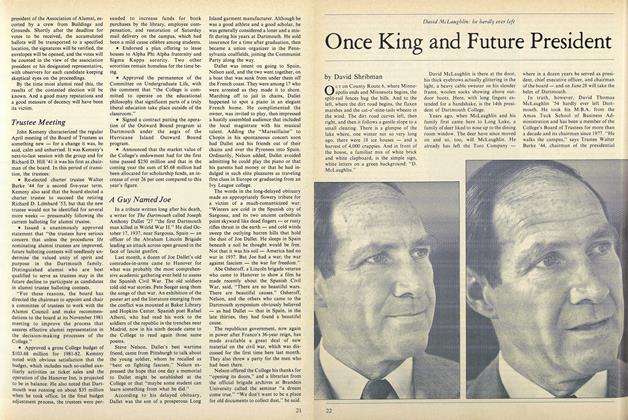

FeatureOnce King and Future President

May 1981 By David Shribman -

Article

ArticleMind for Adventure

May 1981 By Don Rosenthal '81 -

Article

ArticleGreat Issues, Etc.

May 1981 -

Sports

SportsThe Club Set

May 1981 By Brad Hills '65