1850: the crisis of Union 'No sir! No sir! There will be no secession'

MARCH 1982 Michael BirknerTHE weather that January evening, 132 years ago, complicated the old man's plans but failed to keep him at home. It was January 21, 1850, and snow was falling heavily in the nation's capital. This was not a night for casual travel, but Henry Clay, 72 years of age and in faltering health, was not venturing from his rooms in Washington for light exercise or socializing. He was heading, alone, several blocks away to the home of Daniel Webster on Louisiana Avenue, and his mission had the most portentous overtones. Clay meant to enlist Webster - his ally, rival, and peer in the Senate for so marly years - in a campaign to save the Union.

Alarmed by the fierceness and radical- ism of the polemics that passed for debate in the Congress since it had convened a month earlier, and dismayed by the lack of flexibility in President Zachary Taylor's approach to the problems then vexing the country, Clay had come to see Daniel Webster to lay out a comprehensive plan for sectional conciliation. Without the Massachusetts senator's sincere and firm support, Clay knew, his compromise had little prospect of winning public acceptance in the North and hence in the Congress.

Over the course of an hour, Webster heard Clay out, and he responded at the end of their conference in plain language: He would sustain Clay's objectives and his compromise plan. The means Webster would employ were left unsaid, but his broad pledge was sufficient. Clay hurried home to bed, cold and wet, but satisfied that his last major effort on behalf of sectional harmony had a fighting chance.

SLAVERY lay at the heart of the crisis of 1850. Since the founding of the Republic, the South's peculiar institution had been a source of awkwardness and tension, a flammable though largely manageable issue in national politics. By 1850, awkwardness on each side had given way to angry polemic, and the national debate intensified over the future status of slavery in the territories won in the Mexican War. Late in 1849, one of those territories, California, petitioned for admission to the Union as a free state. California became a symbol and a flashpoint for southerners worried about their prospects in a Union dominated by free states, angry at alleged northern slights to the South's honor and dignity, and obsessed with fears for the future of their slave system. Should California be admitted as a free state, southern rights' men warned, secession was the South's logical and proper course.

Moderates like Clay and Webster listened to the assertions of extremists on both sides of the issue with growing dismay and anxiety. Their own repeated attempts to soothe sectional feelings, and to reinforce the values Americans shared, seemed increasingly undermined by the words and actions of younger men who, perhaps because they took stability for granted, did not recognize the tragic consequences of disunion.

Clay did recognize the consequences and feared them deeply. So he formulated his plan for compromise and sought Webster's aid. Together, they would work to defuse the crisis of the Union and to strengthen the intangible but nonetheless compelling strands of memory and emotion that helped bind a diverse people together under one flag and one government.

CLAY'S program for conciliation was presented to a packed Senate on January 28 and 29, 1850. Sensitive to southern insistence that only a broad settlement of all sectionally tinged controversies was acceptable, Clay had pieced together a seemingly diverse package. The principal parts of his plan provided for the admission of California as a free state, the organization of Utah and New Mexico as territories without reference to slavery, abolition of the slave trade in the District of Columbia, and a new and strengthened law for the return of fugitive slaves. Despite their evident variety, the proposals were bound together by two broad concerns: to provide concrete concessions to public opinion in each section and to remove the slavery issue, insofar as possible, from politics.

Though feeble as he addressed his colleagues and a large audience in the gallery, Clay was sustained by the knowledge that Webster supported both his broad objectives and his practical remedies. For his part, Webster's inclination to back compromise was reinforced mainly by a conviction that Clay was right, that mutual con cession was essential or the center would not hold. In truth, the easiest course for Webster in. 1850, and the course most consistent with his avowed antislavery principles, would have been to oppose the South. To back Clay's compromise, with its fugitive slave law and without a positive prohibition of slavery in New Mexico and Utah, was dangerous to a northern man with future political ambitions. Yet this is what Webster had pledged to support. Is it any wonder that in the weeks following Clay's presentation, Webster hoped that he would not have to enter the ongoing debate in an substantial way?

THROUGH much of February, Webster tried to convince himself and his friends that there was no need to be frightened for the Union. The most pressing issue - California's petition to enter the Union as a free state - could be resolved without sectional "disruption." "If, on our side, we keep cool," he told his Massachusetts ally Edward Everett on February 16, "things will come to no dangerous pass." Perhaps Clay's plan and the Kentuckian's heartfelt plea to the nation for harmony would carry the day.

Webster's hopes for calm proved illusory. By the third week of February, he no longer claimed that by simply remaining "cool," sectional antagonisms would dissolve. His pledge to Henry Clay was coming due.

The shift in Webster's position from optimism to the conviction that a genuine secession crisis was in the making may be linked to concurrent events within and outside Washington. On February 16, the day Webster wrote optimistically to Everett, the House of Representatives had voted to table a resolution endorsing the Wilmot Proviso, which would have prohibited slavery in the new territories. Two days later, however, Georgia Congressman Alexander H. Stephens led a successful southern filibuster in the House obstructing the admission of California without a decision regarding the status of New Mexico and Utah. And on the 23rd Stephens joined his Georgia colleague Robert Toombs in a visit to the White House, where a tense dialogue with President Taylor ensued. When Stephens and Toombs warned the President that the South would secede from the Union if its concerns were not addressed, the President responded with a Jacksonian dictum that any secessionist act would be crushed. Reports of the exchange spread rapidly through Washington, dashing any lingering hopes that the President would endorse a compromise acceptable to his native region. Finally, and perhaps most ominously, southern efforts to convene a June convention in Nashville, Tennessee, to weigh options in the crisis - including the possibility of secession - were advancing to widespread publicity despite the conciliatory moves of Henry Clay. That the Nashville Convention enjoyed widespread support in the South was made evident to Webster on February 23 when, in a meeting with southern Congressional leaders, he was shown letters demonstrating the strong views of their constituents.

It was in this context, and in an increasingly grave frame of mind, that Webster began work on the last great speech of his long political career.

The news that Webster intended to make a formal address spread rapidly in Washington during the early days of March. The famed senator's public silence since the session had opened contributed to the keen interest in the speech. What position Webster intended to assert was a mystery to all save Henry Clay, a few close friends, and, strangely enough, John C. Calhoun.

To gauge the mood of the South, Webster met with his old adversary Calhoun at the latter's rooms in the capital. The drama of the meeting was heightened by the approach of Calhoun's own speech in the Senate, scheduled for March 4, and by the awareness of both men that the South Carolinian was approaching the end of his earthly mission. Closeted with Calhoun, Webster discussed the current crisis at length and with full candor. Whatever their differences had been in the past - and they had been both numerous and fundamental - each man deeply respected the other and held nothing back. Webster in particular benefited from this confidence, for he needed from Calhoun some hint of what would satisfy the South. The two old men spoke together for more than an hour, each outlining the essentials of his position, each expressing respect for though disagreement with, the other's views. Perhaps most important, Webster left Calhoun's rooms convinced that despite the South Carolina senator's own fierce and fixed commitment to southern rights, he would welcome a Union speech by Webster of Massachusetts.

Calhoun's own speech on March 4, read for him by Senator James M. Mason of Virginia, was unequivocal. He intended not to praise Clay's compromise proposals but to bury them. The South, he said, had no concessions to make. Maintenance of the Union depended entirely on what the North was willing to concede. His speech emphasized the need to restore equality between the North and South which he claimed had been dissolving slowly for a generation and which he attributed to northern "aggressions." Northern "agitation" on the slavery issue must cease. Finally, he hinted at the need for constitutional protections for southern interests, perhaps including a dual presidency. Though Calhoun's remarks were the equal of his many previous efforts in their piercing realism, the substance of his anti-compromise position offered nothing moderates could embrace.

Yet Calhoun's hard line did have its value for Webster. It underscored the depth of southern-rights sentiment and the immediacy of the crisis at hand. Its very fierceness drove home the urgency of the South's unhappiness with current events. No man, on reading Calhoun's words, could fairly claim that southerners were simply posturing in their talk of disunion. Paradoxically, Calhoun's tough talk increased the chances that the Union could be saved, because it made evident the South's earnestness. Moreover, as Webster quickly perceived, Calhoun did not speak for all the South. There was a body of southern opinion, particularly among Whigs and independents, that could accept

the admission of California provided the North made concessions on other matters. To this audience Webster would direct much of his argument on the seventh of March.

Once Calhoun had had his say, the stage was set for the dramatic highlight in the crisis of 1850 - Webster's formal speech. A crowded, excited Senate convened on March 7, with private citizens jamming every gallery seat and crowding the aisles. Senator Isaac Walker of Wisconsin held the floor but quickly relinquished it to his colleague from Massachusetts. "Mr. President," he noted, "this vast audience has not come together to hear me . . . there is one man . . . who can assemble such an audience. They expect to hear him, and I feel it to be my duty ... as it is my pleasure, to give the floor to the Senator from Massachusetts."

WEBSTER rose, and after thanking Walker for his courtesy, commenced with the words that are so familiar, and yet still thrilling, to us: "I wish to speak today," he said, "not as a Massachusetts man, nor as a Northern man, but as an American.... I have a part to act, not for my own security and safety, . . . but for the good of the whole, and the preservation of all. . . . I speak today for the preservation of the Union. Hear me for my cause."

Having set the tone by announcing at the outset his commitment to the Union, Webster devoted the body of his threehour oration to a deft analysis of the causes of conflict between the sections - rooted, as everyone recognized, in slavery - and to an appeal for moderation, obedience to the constitution, and renewed faith in America's noble destiny.

His words were deftly crafted to cool passions and convince his audience that harmony made far more sense than conflict, that the current crisis could be resolved, and that a dissolution of the Union was unthinkable. Each side, he said, had legitimate grievances; at the same time, each was making some extravagant demands that simply had to be withdrawn. In Webster s view, the vexing question of Slavery in the territories had been blown entirely out of proportion. It was, he argued, simply an abstraction which was needlessly paralyzing the nation at a time when important work remained undone.

Following an extended survey of changing attitudes towards slavery in American history, and a recollection of the circumstances surrounding the admission of new states to the Union since 1800, Webster evenhandedly rejected southern demands for legislation opening New Mexico and California to slavery and likewise condemned northern insistence on legal prohibition of slavery there. The South's position was unrealistic, the North's ungenerous and, for that matter, unnecessary.

Webster saw what others failed to see that slavery had no future in the Far West. California, he noted, was already on record against slavery, and the peculiar institution could never thrive in New Mexico's arid climate. "Who," he asked, "expects to see a hundred black men cultivating tobacco, corn, cotton, rice, or anything else, on lands in New Mexico. . . ?" The territories won in the late war, he added, were "destined" to be free, and northern efforts to ram the Wilmot Proviso down southern throats were ill-advised. Why taunt the South with the Proviso, given the geographic and climatic realities? "I would not take pains uselessly to reaffirm an ordinance of nature, nor to reenact the will of God." For Webster, if men North and South of the Mason and Dixon line simply acknowledged that slavery had no future in the new territories, much of the current rancor would dissolve.

Nonetheless, on other issues, Webster argued that each section had legitimate complaints. He agreed with the South, for example, that abolitionism was pernicious. The operations of abolition societies had, over the previous 20 years, "produced nothing good or valuable...." All that they had achieved was to anger the South and encourage a counter extremism and agitation. Without impugning the motives of individual antislavery activists, Webster offered a sharp critique of their moral absolutism, suggesting in the process that abolitionism was not morally uplifting but rather morally obtuse and unChristian.

Similarly, he endorsed the South's demand for a strengthened fugitive slave law. Anything less than a new law was injustice to the South, and anything less than full enforcement of the law violated the Constitution. "Wherever I go, and whenever I speak on the subject, and when I speak here I desire to speak to the whole North, I say that the South has been injured in this respect, and has a right to complain."

Other southern grievances won less sympathy. Southerners' insistence on the suppression of northern petitions and legislative resolutions against slavery, and newspaper comment critical of the South, Webster observed, were outside the bounds of government to influence.

To charges, most recently made in the Senate by Louisiana's Solomon Downs, that slavery was a more humane and practical system than the free labor system of the North, Webster offered a spirited and effective rebuttal. "Who," he asked, "are the laboring people of the North? They are the people who till their own farms with their own hands; freeholders, educated, independent men. . . . Let me say, Sir, that five-sixths of the whole property of the North is in the hands of laborers of the North; they cultivate their farms, they educate their children, they provide the means of independence. If they are not freeholders, they earn wages; these wages accumulate, are turned into capital, into new freeholds, and small capitalists are created. And what can these people think when . . . the member from Louisiana undertakes to prove that the absolute ignorance and the abject slavery of the South are more in conformity with the high purposes and destiny of immortal, rational human beings, than the educated, the independent free labor of the North?"

In all of his comments to this point, Webster had maintained a relatively low key, but in the closing passages he deliberately shifted tone to highlight his contention that secession as a response to sectional differences was unnatural, unthinkable, impossible. "Peaceful secession!" he exclaimed. "What would be the result? Where is the line to be drawn? What states are to secede? What is to remain an American? What am I to be? An American no longer. Am I to become a sectional man, a local man, a separatist, with no country in common with the gentlemen who sit around me here? . . . No sir! No Sir! There will be no secession."

The virtues of American democracy, Webster concluded, were not theory but fact. "In all its history," he observed, the American nation "has been beneficent; it has trodden down no man's liberty; it has crushed no state. Its daily respiration is liberty and patriotism, its yet youthful veins are full of enterprise, courage, and honorable love of glory and renown." Since its founding, the American Republic had prospered and grown to cover a continent, bounded by "two great seas of the world." Nature itself pronounced a verdict for unity. Hence, at the close of his address, Webster summoned his audience to imagine the ornamental border of the buckler of Achilles:

Now, the broad shield complete, the artistcrownedWith his last hand, and poured the oceanround;In living silver seemed the waves to roll,And beat the buckler's verge, and bound thewhole.

THE speech was an immediate sensation, not simply in Washington but across the expanse of the land. Prominently featured in major newspapers and published in a pamphlet edition of 100,000 copies, it was read with the most intense feeling. Significantly, some of the strongest reaction - virtually all favorable — came from the South. William Jones, an Alabama Democrat, claimed to speak for many when he offered Webster "my most heartfelt thanks for the noble & patriotic stand you have lately taken in the U.S. Senate for our common country. "James B. Thornton, of Memphis, Tennessee, put the matter succinctly: "Your speech, sir, has created new hopes [for the Union]." Southern newspapers, on the whole, were equally ardent in embracing Webster's magnanimity. Even the normally radical Charleston Mercury described the Massachusetts senator's effort as "emphatically a great speech, noble in language, generous and conciliating in tone."

In the North, the seventh of March speech received a markedly different reception. Though Webster was cheered by editorials in the Boston Courier and the DailyAdvertiser praising his patriotism, and by the dinners, public letters, and Union rallies organized by leaders of the business and professional classes, the initial reaction to his speech in New England was mainly negative, in some quarters virulently so.

Antislavery men were deeply dismayed some to the point of disgust, that New England's greatest statesman and orator should reject the Wilmot Proviso and worse, approve a strengthened fugitive slave law. Ralph Waldo Emerson called Webster's absence of moral sensitivity

"degrading to the country." "Infamy," he wrote, "has fallen on Massachusetts." The poet Whittier lamented "the light withdrawn which once he wore," and in his memorable poem Ichabod stigmatized Webster as a "fallen angel" whose soul had fled. Theodore Parker likened him to Benedict Arnold, Horace Mann compared him to the devil, and James Russell Lowell characterized him as a statesman "whose soul has been absorbed in tariffs, banks, and the constitution, instead of devoting himself to the freedom of the future." Webster's speech, the abolitionist Wendell Phillips declared in a Faneuil Hall meeting, reminded him of what might have happened during the Revolution if Sam Adams "had gone over to the British or John Hancock had ratted."

The epithets doubtless stung, but they did not surprise or sway Webster. Convinced that his "truth-telling" approach was essential to a settlement of the current crisis, he plunged ahead with increased resolve. He vowed to work "to the full extent of my power, to cause the bellows of useless and dangerous domestic controversy to sleep, & be still."

This was no small assignment. Passions were at a high pitch. As has frequently been the case in American history, political commitment tended to be least intense in the center of the political spectrum - precisely the position Webster had staked out. To stimulate and nurture a passion for moderation and to reaffirm a broad and inspiriting Unionism was Webster's charge and his main priority in 1850.

Throughout the spring and summer, he waged this fight with patience, consummate skill, and, for a man his age, remarkable vigor and spirit. He was active on various fronts - in the Senate, for exampie, he continued his efforts to pass Clays compromise, either as a package or, preferably, seriatim in separate bills. At home in Massachusetts for several weeks in March and April, and again later in the spring, he wrote and planted newspaper pieces favorable to compromise, responded to public letters endorsing his speech, and debated in the press with his critics.

IT would be poetic to say that Webster's Speech and his unstinting efforts on behalf of compromise in subsequent months resolved the great issue. But it would not be true. For all its undoubted power as a discourse, there is no evidence that Webster's seventh of March address changed a single vote in the Congress. At most, one can safely say that Webster's eloquence forced Americans to think deeply about their Union, to weigh its benefits and their republican heritage against the evident perils of secession and war. If Webster did not sway votes, he did call into play emotions, as historian David Potter observed, "which prepared the American people for conciliation" - no mean achievement.

Problems nonetheless remained with Webster's approach to the issues that divided the country, not least of which was the growing strain of opinion in the North that a compromise on slavery was morally wrong. Webster continued to press for constitutional principles and the observance of law. Hence his support for a strengthened statute regarding fugitive slaves, on the ground that the Congressional Act of 1793 mandated the reclamation of slave property. In a strict legal sense, Webster was on sound ground, but what he refused to concede, in 1850 or later, was that other considerations may be relevant in the making and enforcing of laws. Webster's enemies, the rabid antislavery men of the North, argued with considerable power that a political act had to be morally as well as legally right — that, as Senator William Seward of New York put it in his own response to Webster, it had to conform to a higher law as well as accord with the mundane Constitution.

Similarly, Webster's impatience with those who sought legislative prohibition of slavery in the new territories was based on premises that were at best debatable and at worst, dead wrong. He sincerely believed that the climate and soil in New Mexico were inhospitable to slavery, thus rendering abstract the whole question of legally protecting or forbidding the introduction of slaves across its borders. The weakness of this perspective was at least twofold. First, Webster underestimated, perhaps even willfully ignored, the adaptability of slavery to non-plantation situations, notably in mines and factories. Slaves had performed effectively in such circumstances for generations, and there was no natural bar to their doing so in New Mexico. Second, Webster failed to grasp the depth of public opinion on each side of the question. Slavery in the territories was not merely an abstraction but a matter that affected thousands of lives - and millions of perceptions - in critical ways. For all his magnificent powers and the honest patriotism of his position in 1850, Webster failed to grasp that the resolution of America's dilemma regarding slavery was irresoluble short of Civil War.

The balance sheet on Webster and the Crisis of the Union is difficult to draw, entailing as it does the kinds of "moral" judgments Webster himself was loathe to make. To his critics in 1850 and for many years after his death, Webster was hopelessly obtuse, a man without conscience, wed to the pocketbook, and interested above all in personal gain.

There is, to be sure, a measure of truth to this, both over the course of Webster's career and in his final years when his quest for the presidency took on an air of desperation. Yet that measure of truth is not the truth. Webster's critics failed to credit his deep commitment to sectional comity within the constitutional system established by the framers, just as they failed to acknowledge the depth and sincerity of his attachment to the "sacred trust" implicit in American experience. On a less elevated plane, they failed to see the immediacy of the problem that Webster was addressing - a true secession crisis at a juncture when the outcome was even less "inevitable" than that following the crisis of 1861.

AMERICANS had essentially two choices in 1850: to fight with one another or to calm down and accept some middle ground, be it in the form of a compromise or, at minimum, a kind of truce. To Webster's relief and the relief of the great mass of the public, the middle ground ultimately prevailed in the sweltering months of that summer. Credit for this belonged in large measure to Clay and Webster, to the new president, Millard Fillmore (who took on Webster as his chief adviser and pursued a firm pro-compromise course), and, not least, to Senator Stephen A. Douglas of Illinois, who in August and September shrewdly broke Clay's stalled omnibus bill into its constituent parts and engineered different majorities for each individual bill.

The Compromise of 1850 was a milestone in American history. Not only was it the last great episode in which the magnificent Senate triumverate - Clay, Calhoun, and Webster - would share the stage, it was a signal to the American people that some final reckoning with slavery would have to be made. Webster tried with all his energy and talent to eliminate the slavery issue from politics. He failed.

But in other respects, his role in the crisis of 1850 was triumphant. By his labors, he bought time for younger statesmen to work out new arrangements to contain sectional strife over slavery, if indeed such arrangements were possible. And when they proved not to be possible, Webster's fervent and heart-touching case for the American nation, wed to the growing moral strength of the antislavery crusade, made possible the successful prosecution of a terrible but irrepressible conflict between the North and South. Under the leadership of Abraham Lincoln, the American people reaffirmed the principles of 1776 as well as the perpetuity of the nation, and did so on terms Webster had made so familiar. "Liberty and Union, now and forever, one and inseparable."

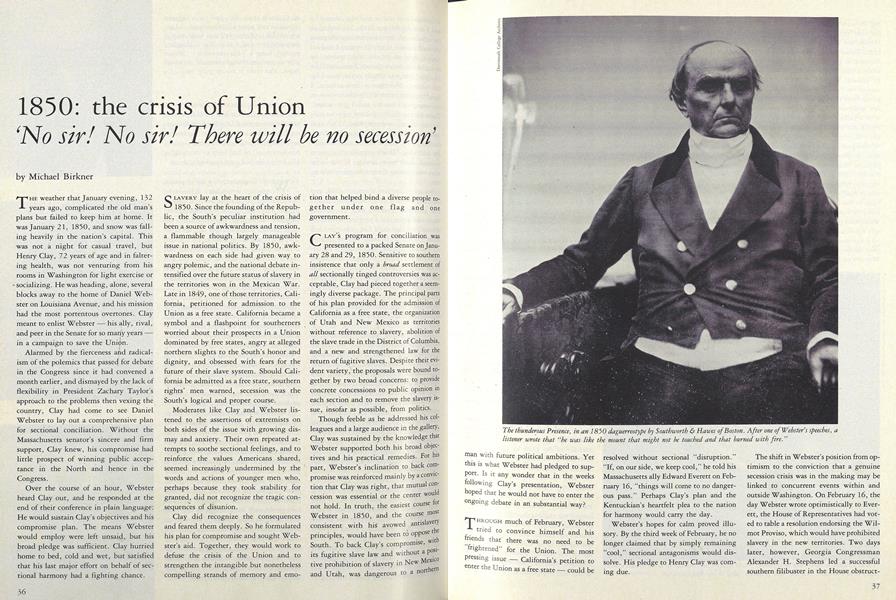

The thunderous Presence, in an 1850 daguerreotype by Southworth & Hawes of Boston. After one of Webster's speeches, alistener wrote that "he was like the mount that might not be touched and that burned with fire."

"I would rather be right than be President, " said Henry Clay, but like Webster he had wantedbadly to be President. His son, like Webster's, died in the Mexican War.

John C. Calhoun, Yale man and champion of states' rights, died soon after his speech againstClay's compromise. His last words: "The South, the poor South."

Webster misjudged, the fury of the Boston aboli-tionists, who issued this broadside after passageof the Fugitive Slave Act.

Michael Birkner is associate editor of The Papers of Daniel Webster. This article isadapted from an address to the New HampshireHistorical Society on January 18, the 200 thanniversary of Webster's birth.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureThe naivete of nuclear rivalry

March 1982 By George Kennan -

Feature

Feature'One day it came to me: sherry for breakfast was a good idea.'

March 1982 By Shelby Grantham -

Cover Story

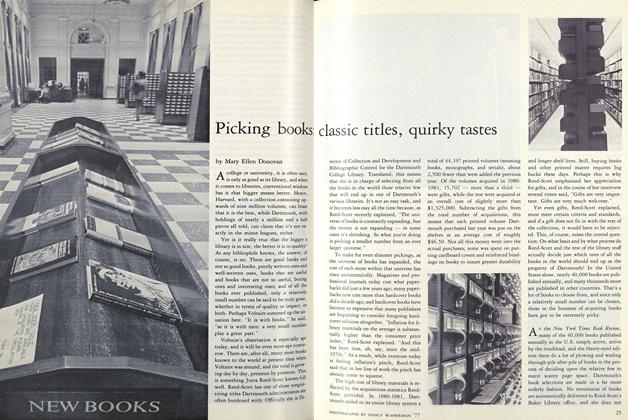

Cover StoryPicking books Classic title, quirky tastes

March 1982 By Mary Ellen Donovan -

Article

ArticleSomeone wrote them, but did anyone read them?

March 1982 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1954

March 1982 By John L. Gillespie -

Class Notes

Class Notes1959

March 1982 By William G. Long

Michael Birkner

Features

-

Feature

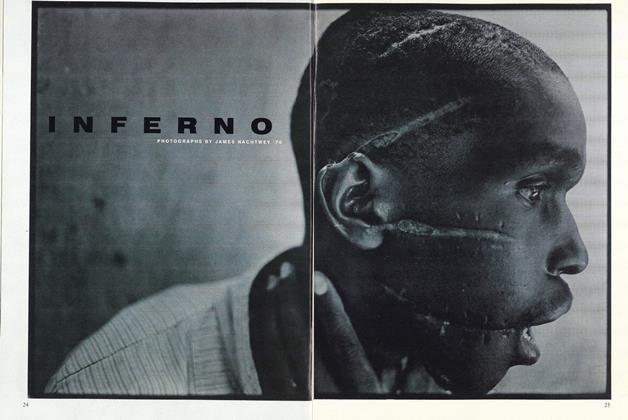

FeatureInferno

JUNE 2000 -

Cover Story

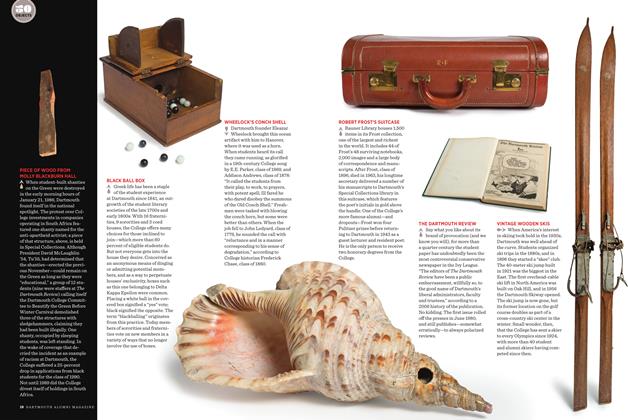

Cover StoryBLACK BALL BOX

MARCH | APRIL 2014 -

Feature

FeatureRETIRING FACULTY

JUNE 1971 By B.B. -

Feature

FeatureRichard Hovey: The Incomplete Arthurian

DECEMBER • 1986 By Daniel P. Nastali -

COVER STORY

COVER STORYTelevision’s Wonder Woman

MARCH | APRIL By Jennifer Wulff ’96 -

Feature

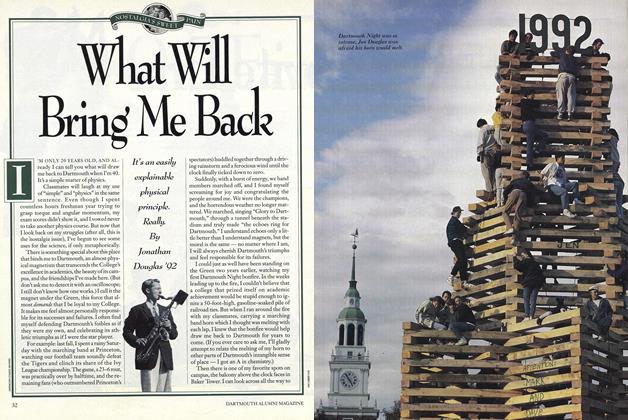

FeatureWhat Will Bring Me Back

MARCH 1991 By Jonathan Douglas '92, Richard Hovey