It is too happy a coincidence to ignore the fact that Pilobolus Dance Theatre and the Concord String Quartet, the two premiere arts groups with Dartmouth connections, are both celebrating their tenth anniversaries during 1981—82.

And the end of their first decade finds both groups not only surviving but thriving. They have risen to the top of fields crowded with high-caliber contenders, along paths littered with drop-outs. Reams of laudatory reviews, strings of awards, numerous television specials, and appearances at celebrated festivals and concert halls around the world document their success. Recently, Pilobolus marked its tenth anniversary with a three-week Broadway run, and the Concords commissioned three new works from major composers and gave three concerts at New York's Alice Tully Hall.

Explaining the two success stories, though, is harder than documenting them. There's the obvious artistic, professional talent. But it's like Ivy League college admissions ― there are lots of highly qualified dancers and musicians, but only a few make it to the top. How have Pilobolus and the Concords sustained themselves along the path to the pinnacle? What keeps four or six individuals together in a highly emotional business? Members of both groups profess not to spend much time contemplating such matters. As Robbie Barnett of Pilobolus put it, "We don't think about the group dynamics. It's academic. We just do whatever we have to do to make the dances appear." And his colleague Jonathan Wolken said, "God knows what keeps us together ― some mystic glue perhaps." Nevertheless, some basic patterns common to both groups emerged.

PILOBOLUS was conceived and born at Dartmouth, and its infancy was spent in the environs of Hanover. The troupe was founded by two '71s ― Moses Pendleton and Jonathan Wolken ― shortly after their graduation. They had taken a dance course together their senior year and had decided to try cultivating some of the ideas the class had planted. Talking two other students from the course ― Robbie Barnett '72 and Lee Harris '73 ― into joining them, they substituted innovation for experience in creating a style that fused dance, acrobatics, and theater. The group also pioneered a collective choreographic method that was an outgrowth of their communal life on a Norwich farm growing vegetables and cutting wood together as well as dancing as a foursome.

While defying every dance convention, the group was an immediate hit with both audiences and critics. A few years later, the four men were joined by Alison Chase, their former teacher, and Martha Clarke, and Harris was replaced by Michael Tracy '73. Shortly after that, the group moved its base of operations to Washington, Connecticut. Now, Tracy is the only early member still actually performing with the company. The other five have been replaced on-stage by new dancers, among them yet another Dartmouth graduate

Jamey Hampton '76. But the other "originals" still consider themselves very much a part of Pilobolus and constitute a board of directors that sets policy and provides artistic direction. Recent years have seen several other changes in the company: It has renounced some of its collective, communal orientation and its members now lead relatively separate lives; also, the company now has a formal administrative structure and staff, while in the early days the dancers prided themselves on doing everything - from lighting design to company management.

Unlike Pilobolus, which sprang from Dartmouth soiL, the Concord String Quartet was transplanted to Dartmouth as a fully formed entity, although it has grown to maturity under the aegis of a mutually rewarding relationship with the CollegeThe four Concords ― violinists Mark Sokol and Andrew Jennings, cellist Norman Fischer, and violist John Kochanowski had three things in common when they came together: excellent training as classical musicians, a passion for quartet music, and a connection with Robert Mann, first violinist of the pre-eminent Juilliard Quartet. It was Mann who pulled the strings that got the four together, and he has been a mentor to the group ever since.

The fledgling quartet began to make a name for itself and to get concert bookings ― including one at Dartmouth during its first season. Peter Smith, then director of the Hopkins Center, had considered for some time having a quartet permanently in residence at the College and was looking at various young quartets as possibilities. Practically, philosophically, and personally ― as well as musically - the Concords seemed a good match, so he brought them back. They came for another concert in the winter of 1973-74, moved bag and baggage to Hanover the next summer, and have been here as quartet-in-residence ever since.

Actually, it might be more appropriate to say that they moved everything but bag and baggage to Hanover, since they're often on the road touring and recording between concert and class commitments at the College. Although in the early years the Concords kept a grueling schedule ― rehearsing 14 hours a day, seven days a week, and touring 12 months of the year ― they now reserve two months free of all concert dates, and rehearsals are more likely to run six hours. That they have had such flexibility in their schedule has been in good part responsible for their success ― which has, in turn, enhanced their value to Dartmouth.

THE relationships within a dance company or a string quartet seem hinged on several factors. The diversity among its members ― and the fact that diversity can be both a source of creative energy and a cause of conflict ― is a key element.

Concord cellist Fischer explained the importance of diversity: "Some people think that a quartet is homogeneous that there are four people who play identically. They consider it a compliment to say that it sounds like one instrument. But the composers who have really used the quartet medium in the most fruitful sense have recognized each instrument as a separate entity and have figured out ways to make them pull apart and come together again to create dramatic impact and to bring a third dimension to the scope of the work.

"And when you play with three other people whom you really admire," he concluded, "each has different points of view to bring."

Diversity is personal, too, as well as professional. "We have quite distinct personalities," said Fischer's colleague Jennings. "The way we feel and are as people differs tremendously. There's a lot of coming apart and coming together ― an ebb and flow."

Diversity among its members is also recognized by Pilobolus. "It's a myth to think that any one group can stand still," noted Wolken. "From hour to hour and from day to day there are differences the moods, the relationships, the people all change."

One of the beneficial effects of diversity is that it drives members to seek outside professional experiences, the fruits of which can be brought back to enrich and renew the core group. The branching out of five of the original Piloboleans is an obvious example. "Pilobolus has been allowed to continue as an entity," explained Barnett, "by the fact that we have all been able to do things outside the structure of Pilobolus." He and Clarke joined a couple of years ago with a third dancer to form a new dance group called Crowsnest; it is modeled in some ways on Pilobolus but is smaller and thus more flexible and informal. Pendleton and Chase are exploring a different style of dance as a duo called Momix; they have also done choreography for several European opera companies, and Pendleton is currently working on a documentary for CBS-TV. Wolken is also trying his hand at choreography for other groups and at a totally new venture auto-racing (he explained that both dance and this seemingly incongruous new passion satisfy his love of motion and his urge to control a finely tuned mechanism). Barnett pointed out that all these experiences have kept them fresh. "They help us get new ideas," he said. "We can come back to Pilobolus with a vision of the work that's not possible without outside stimulus. It's hard after that number of people interact on that level for that number of years to keep your ideas from solidifying."

Barnett's colleague Wolken expressed similar thoughts: "Pilobolus is now in its second phase of life; we've gone through a little cell division, a little mitosis. The originals like Moses and Robbie and myself have gone through so much personal and choreographic growth that we all recognized it was time for a change. But the suffering and slavery that were put into Pilobolus have bonded us together despite our wide-ranging differences. We can still come back and touch on that."

The Concords agree. "When you go off on your own," said Fischer, "to play a recital, for example, different things happen. It's like a kaleidoscope ― you shift the pattern. You may hear something you hate and want to make sure you don't do; or you may hear something you love and want to try out yourselves. So you learn both positive and negative things. You also have to be careful that you don't work so intensely just with each other that you deal too much with details that only you will ever be aware of. You have to keep striving to break out of molds of any kind."

Jennings also pointed to the natural reluctance to change things: "The idea is that if it feels good, if you get a good response, you feel like performing it the same way the next time." Recordings play a large part in the tendency to resist changing a piece, according to violist Kochanowski. "Every time you listen to a recording," he said, "a piece sounds exactly the same. So some people come to expect that it will always sound the same, even when they go to a concert." Fischer seconded Kochanowski's observation, noting that a single recording, or a single concert, is a documentation of the way the musicians feel at that time. "You're true to a certain ideal of a piece at one point in time," he noted. "The idea is that there are so many points of view that are all valid."

In illustration, Fischer mentioned someone who came to three concerts on three consecutive nights and heard the same piece on each progam. "He couldn't believe how different the performances were from night to night," Fischer said "He loved the first night, and then the second night he was shocked that it was so different. The third night he'd gotten used to the idea that it would be different, and then it was different again. It was a revelation to him how different the same thing could be. You learn that every performance is just one possibility, and then there are four different ideas of how to do it again the next time." The same thought was echoed by Pilobolus's Wolken: "You learn that there is never any single way of working together."

While diversity is usually a positive force, both Pilobolus and the Concords attested that it can sometimes produce negative effects. "There are attendant tensions in any group of people working together," pointed out Pilobolean Barnett. "When a group deals with volatile emotional matters, it is normal that they will find it hard to make decisions. By and large over the years, the tensions have been valuable for us, but they can become destructive. It is hard to keep things clear, to talk about just the matter in front of you. Instead of talking about the steps in a dance, you argue about something that happened six months before. But some tension is good for the work ― it creates energy."

His colleagues Wolken and Pendleton concur. "In any relationship that carries on over a long time," said Wolken, "you get to know everyone's weak points. You know how to flatter them, how to anger them. Sometimes it's like wiggling a loose tooth you just can't help making someone react a certain way." Pendleton mentioned the same problem. "For a while it got to seem as though none of us had minds of our own. A thought didn't mean much unless it went through six brains. After a while you lose interest in your own point of view and gain interest in escaping from the argument."

Fischer noted that the problem is shared by quartets: "Many of the ones that break up have found that it's difficult to lose yourself to make compromises. But it's the way issues are resolved, the way progress is made, the way problems are solved. Someone may feel, though, 'Oh, no ― I'm going to lose myself if I give in and play it that way.

As notable as the fact that both Pilobolus and the Concords have conflicts is the fact that they have been able to channel them positively. "It's like a marriage," explained violinist Jennings, "it's not a question of how placid the waters are, but of whether you're able to take conflicts and use them for growth. As long as we're able to deal with differing opinions and actions ― and sometimes there are quite basic differences ― and turn them to our advantage, then we're a viable organization." He carried the marriage analogy even further: "It's also like a marriage in that we can support each other through our strengths and weaknesses. We rely on energy from each other to tide us over low spots. The group is ideally a fusion of the separate personalities, not a subsumption of them. You don't want to make all the members similar ― you want to make the different things work together."

Likewise, Wolken noted about Pilobolus: "When we're faced with a problem, we absorb it rather than fight it. You learn to make compromises." And Barnett explained that while most decisions are made by consensus, it is rare that someone feels so strongly about a matter that they will not make some concessions.

DIVERSITY's importance as a stimulating forceto the groups seems to be balanced by an equally strong cohesive force ― the intense commitment to the creative process that the members have in common. This as much as anything sets a dance troupe or a string quartet apart from a law firm or a group medical practice ― although in many ways an arts group can closely resemble any other small business or professional organization.

Like any growing company," said Barnett of Pilobolus, "we have to deal with cash flow. We're hooked in with the economy. If money is tight, people can't afford to go to the theater, and we don't have the resources to do more choreography." And Pendleton pointed out that in its policymaking role, the Pilobolus board "is just like the board of directors of any company. The Concords, too, respond to economic forces: Their residency hinges on its being financially feasible for the College -nd financially rewarding for them.

But the groups' creative force carries them beyond finances and policy. "Fun has always been a big thing in Pilobolus," said Wolken. "It's so important to keep interested in what you do. Boredom sets in so quickly, and so many people work themselves silly at things that basically bore them. But in Pilobolus, the joy of the discovery process ― finding out what works, what succeeds ― has a power. What moves you is not just the physical process ― it's also emotional, artistic, and logistical. When it all works well together, it resonates so nicely. That power, that control of it all, says so little but suggests so much."

Likewise, Barnett cited "the challenge of discovery and the electric excitement of choreography" and Pendleton "the urgency to try things ― to 'get it on canvas' " as major motivating factors in their work. "When you're working with people who have a shared vision," Pendleton added, "that spirit allows you not only to enjoy it but to thrive. It's a sort of 'mad positivism.'

The Concords reflect the same feelings. "It's terribly exciting to rehearse," said Fischer, "to explore all the possible ways of interpreting a phrase. There's a lot of bantering in the search ― and you hope it will be a lifelong search."

WHATEVER combinations of encouraging diversity and stimulating creativity Pilobolus and the Concords have evolved, they have undeniably worked. As Barnett said, "Pilobolus has endured and mellowed. For it to have functioned for ten years now ― although the dynamic has― changed, we've made some adjustments has surprised many people. It's still a constantly evolving thing, but even so there's been unquestionably low turnover for a dance group."

And for the Concords to have celebrated their tenth anniversary with all four original members is also notable. The group is currently one of only two major quartets in the world (with the Guarneri) that have their original membership. Fischer pointed out that although three European quartets (the Amadeus, the Borodin, and the Italiano) had the same membership for 35 years, the much more common pattern is that of the Juilliard, in which Mann is the only original member after 35 years.

Another factor touched on by members of both groups is the effect of the mere passage of time. "We're all ten years older now," said Barnett of Pilobolus. "We're different people and we deal with the world in different fashions." Jennings said the same thing of the Concords: "We're now ten years old, and you play something differently when you're ten than you do when you're two."

Inevitably, however, the question is asked: How long can the groups expect to remain together?

Pilobolus, in the early days, was extremely ephemeral. Now its fortunes seem much more assured, by two intertwined supports. One is the dance group itself - the formal, on-stage incarnation of Pilobolus. The other is the affirmation of the vision of its founders provided by the group's success. Barnett noted that the performing group could now easily continue into the indefinite future because of its strong administrative structure. And Wolken pointed to the group's founding principles as a source of strength: "The original concept for Pilobolus was as a 'Greater Pilobolus Enterprises' sort of thing. It could have been anything and it just turned out to be dance. That flexibility is important. There's so much creative output in Pilobolus ― why limit it? We can do dance; we can do theater; we can do film. Who knows? We're all ready for a new phase. There will probably be a new look to Pilobolus ― we'll go back to our origins and reinstate and affirm the idea of 'Greater Pilobolus Enterprises.' "

The future of the Concords seems equally secure, although more traditionally so than that of Pilobolus. A serious string quartet has a life span of 30 or 40 years, and the Concords call their tenth anniversary "just a beginning." At the Juilliard Quartet's 25th anniversary, shortly after the Concords had gotten together, Mann reportedly observed to his proteges, "Let me tell you ― the first 25 years are the hardest." "I can see that now," said Jennings on the Concords' tenth.

So in ten years, Pilobolus has retained its essential focus on experimentation, while changing structurally. And in their first decade, the Concords have preserved their dedication and seriousness while making a somewhat less consuming commitment in terms of time. An intriguing insight into these two paths is offered by a look at the sources of the groups' names.

A "pilobolus" is a kind of photosensitive fungus; it bends and twists toward light as it grows, and when it is mature it shoots its spores with tremendous energy over distances of up to 40 feet. Wolken was familiar with piloboli, having spent high school summers working in his father's biophysics lab. He and Pendleton selected it as the title for a dance they choreographed as their final project in the dance class that spawned the troupe. It was an appropriate name then for the dance in which three men bent and leaped outward from a central core. And it is appropriate now to the way in which Pilobolus finds itself branching out into new enterprises.

The Concords, instead of picking a name at random in a fit of whimsy, went about that task in thorough and serious fashion. They found themselves a name by going through the dictionary and trying out every entry with "String Quartet." Not only did "Concord String Quartet" have a nice euphonius ring to it, but it had pleasant associations with Charles Ives's "Concord Sonata" ― a landmark piece in American classical composition. That was appropriate because the group has been a champion since its very beginning of American contemporary music. And the sense of purpose (tempered with humor, for the dictionary hunt must have been an amusing process) that the endeavor suggests is an apt reflection of the Concords' dedication to their music.

In retrospect, despite their protestations about their lack of thought on the subject of group dynamics, the members of both Pilobolus and the Concord Quartet seem to have an unusually keen insight into their working relationships.

The groups are like marriages but more than marriages. They are like businesses but more than businesses. It was probably Wolken who best put his finger on that ethereal "more than" when he referred to "mystic glue." Perhaps the mysterious mucilage Cos which Pilobolus and the Con- cords owe their success is just an intangible version of rubber cement ― that handy adhesive that sticks two pieces of paper firmly together but also allows them to be easily pulled apart.

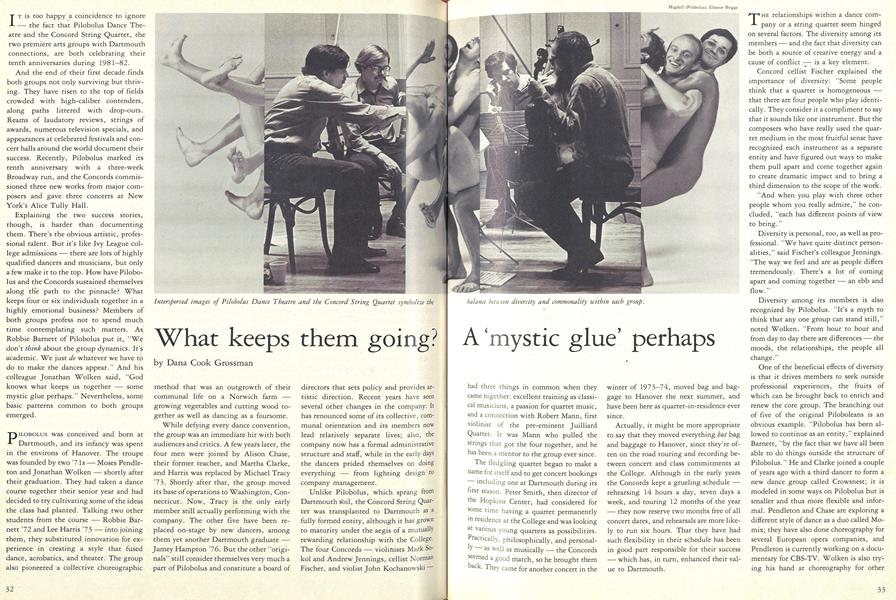

Interspersed images of Pilobolus Dance Theatre and the Concord String Quartet symbolize the

balance between diversity and commonality within each group.

Jennings, Kochanowski, Fisher, and Sokol with mentor Robert Mann {second from right).

For founders Pendleton (top) and Wolken: along way from their senior-year dance class.

Piloboleans Barnett (left), Chase, and Wolken practicing in their Connecticut habitat.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureTerrorism and the Niceties of Justice

May 1982 By Joseph W. Bishop Jr. -

Feature

FeatureImpacts simply positive

May 1982 -

Article

ArticleIn the Wide, Wide World

May 1982 By Peter Smith -

Class Notes

Class Notes1964

May 1982 By Alexander D. Varkas Jr. -

Class Notes

Class Notes1954

May 1982 By John L. Gillespie -

Article

ArticleDartmouth Authors

May 1982

Dana Cook Grossman

-

Article

ArticleVox

October 1980 By Dana Cook Grossman -

Article

ArticleQuirkiness to Taste

December 1980 By Dana Cook Grossman -

Books

BooksMore Than Work

April 1981 By Dana Cook Grossman -

Article

Article"More like a house"

OCTOBER 1984 By Dana Cook Grossman -

Article

ArticleA Post-game Peregrination

OCTOBER 1984 By Dana Cook Grossman -

Article

ArticleCollege to purchase hospital buildings

JANUARY/FEBRUARY 1986 By Dana Cook Grossman

Features

-

Feature

FeatureThe National Scene

APRIL 1970 -

Feature

FeatureOff and Chopping

MARCH 1983 By Jean Hanff Korelitz -

Feature

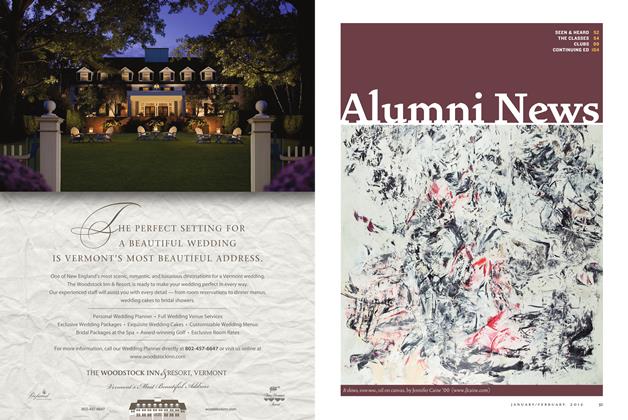

FeatureAlumni News

Jan/Feb 2012 By Jennifer Caine ’00 -

Feature

FeatureGood Teaching: A Case Study

February 1956 By JOHN HURD '21 -

FEATURE

FEATURESibling Revelry

MARCH | APRIL 2020 By LISA FURLONG -

Feature

FeatureValedictory to 1961

July 1961 By PRESIDENT JOHN SLOAN DICKEY