John Morton, Dartmouth's former cross-country ski coach, as well as a two-time Olympian and world master's ski champion, has run up Moosilauke many times, and he has visualized running up Moosilauke many more times. "Visualization is a powerful tool to be used in the development of a positive self-image," he says positively in his classic book Don't Look Back. "When I asked my skiers to imagine that they were gazelles or cheetahs flying effortlessly over the snow, the improvement was astounding." Coach Morton says you can concoct appropriate metaphors for any occasion: "On a long, gradual uphill, you're a powerful locomotive, on a fast downhill, a downhill skier..."

Me, I am a pantry. I am laden at the waist with cheese and butter. My hips are brownies, my thighs are fine imported beer. Thick espresso courses through my veins.

I am Working Man. Responsibilities burden my shoulders. I sit all day and drive at night. I am 30 years old.

From the looks of my Lycra-covered opponents, they are Powerbars and mineral water, bananas and carbohydrates. They are lean, lean, lean. Huge thighs, narrow knees, bulging calves, slim ankles. Triceps. Well-rested and eager to go, 50-mile weeks a commonplace. They are 20.

Well, a couple are 40 and a few are past 50. These tough old veterans have run up this mountain before, lots of mountains. And back down then up another one, just for good measure. I usually don't run up mountains. I've walked up a few, and driven over a couple. I've flown over lots of them, where they look so pretty, like one of those blistered relief maps. But soon we'll all run up Moosilauke, 3.6 miles along the Gorge Brook Trail, from the Ravine Lodge to the cairns and signposts and ruins of the old hotel at the summit. The 3.6 miles I can handle. It's the elevation gain—2,500 feet up over the course of those 3.6 miles—that's the problem.

No, no. Not a problem. There are no problems in this race. You have to think positively. Gazelles and cheetahs are positive animals. The elevation is a challenge, and challenge is what this run is all about. Because skiers love challenges, and the annual Moosilauke Time Trial is a rite of fall for Dartmouth's skiers.

Every autumn since the mid-19605, when Dartmouth's then-ski coach, Al Merrill, got the idea of using Moosilauke's sacred ground as a way to shake the deadwood from his Nordic ski team, Green skiers have assembled at the base of the mountain on the appointed Sunday morning to charge up its slopes. Merrill explained to the boys that if they couldn't reach the summit in under a certain time, say 50 minutes, they could forget about skiing for Dartmouth that winter.

The event became an oft-told tale in skiing Valhalla after Merrill coached the national team and offered the nation's elite skiers a similar challenge, only in the teeth of a November blizzard. Word spread: forget the University of Utah's Agony Time Trial and Colorado's Green Mountain Grand Prix (three miles, 2,500-foot gain). For a test of pure stamina, leg strength, and mental toughness, Moosilauke was it.

Subsequent ski coaches maintained the tradition, adding downhillers, but stopped cutting people on the basis of how they performed on Moosilauke. After all, the whole point of Alpine skiing, at least, is to go fast down a mountain, not up it. But it's still an important part of pre-season "dryland" conditioning, along with the other peculiarities of ski training: bounding up the steps of the visitors' side of Memorial Stadium while wearing leaded vests; running through the woods carrying ski poles; roller skiing.

But nothing beats a good stiff slope. "Running up a mountain is the best way to test what kind of shape our skiers are in," says Ruff Patterson, Dartmouth's director of skiing, the cross-country ski coach, and a former Olympic coach. He goes on to talk about measurements of aerobic capacity and the ability to process oxygen, but what it all really means is fitness.

And toughness. "This is an excellent way to see how well people deal with the pressure of competition," Patterson adds. "The mountain is really intimidating and this makes you develop a strategy for how to deal with it."

Well, I've always liked to think of myself as a tough guy. And when Patterson extends an invitation to join 30 or so undergraduates and a few alumni for the time trial, I say heck, yeah, I'd love to do it. Good test of my, ah, ability to develop strategies under pressure. Sure, Ruff. Ten a.m. start? Not earlier? Okey-doke. I figured even if I was in pretty good—not great—shape, I could fake my way up Moosilauke. Maybe not gazelle-like, but at least like a bighorn sheep.

RULE NUMBER ONE: YOU CANNOT fake your way up Moosilauke.

I should realize this as soon as I arrive at the Ravine Lodge. The lodge's crew is in the process of m closing the place up for the winter, sort of like the begin- ning of The Shining. Most of the skiers assembled there are pretty loose, joking, stretching, discussing the best way to deal with the mountain, waiting in line for the bathroom. But I start talking to a couple of women—freshmen, it turns out—and they're nervous. NERVOUS!

"What's there to be nervous about?" I ask, nursing a cup of coffee.

I ask if they are Nordies. The one with the Dartmouth Skiing sweatshirt says she is. But greyhounds look nervous, too, and they go really fast. She, I decide, is a greyhound. Maybe my prerace goal of 50 minutes needs some rethinking.

Then I meet John Donovan, a former director of outdoor programs for Dartmouth and a top-ranked master's skier who is milling around the start area with a bunch of hyper-fit older guys. They do not look nervous; they look bored. In the animal hierarchy of visualizers, most of these guys are definitely leopards. The oldest one, art history professor Robert McGrath, is a lion, maybe not th fastest one in the pride but the baddest, the one who gets to eat as much of the dead Thompson's gazelle as he wants. Me, I've gone from being a bighorn sheep to, oh, I don't know, a St. Bernard. I'll get there, but not in a big hurry.

Donovan offers me some avuncular advice: "The most important thing to do is to stay within yourself. Don't go anaerobic. Don't get out of breath. Don't blow up. Walk really fast if you feel like you can't run. The first third is runnable. It gets steep just after the "Last Sure Water" sign.

You can speed-hike there, Once you A get above tree line it flattens out and you can run to the finish. And remember And then we are off, one at a time, in 30-second intervals, just like a cross-country ski race. The starters call names and numbers, you approach the line, they yell "Hup," and off you go. Some of the runners sprint into the woods. I go last, jogging into the woods at what I feel is a reasonable clip.

I AM A LINT TRAP.

If I had an alarm, it would be ringing. I don't breathe, I wheeze, as if my intake is clogged. I'm bounding from rock to rock along the Gorge Brook, following the muddy footsteps of all the other runners. It's a clear, cold morning, and the little patches of snow that the sun had started to melt at the starting line become deeper and more resistant to light the higher we get. The preceding 42 runners have turned the trail into a purgatory that alternates between mud and snow packed into ice. I slip and fall once, twice. I can see the bright red shirt of the runner in front of me, and gain on him, wanting to catch him. He is a friend of mine, or was before Moosilauke. have seen this guy almost puke during an early morning run through a table-flat zoo, and I should not be behind him.

But something is going wrong with my lungs. I feel like there's a brick on my chest and a shopping cart on my back. The strains of Beethoven's Ninth Symphony, blasted from my friend's truck's tape deck in a psychological operation before the race, have turned into a two-word mantra from "Beavis and Butthead" "This sucks." And the worst part is that I'm only seven minutes into this thing.

I decide to speedwalk.

After 20 minutes I reach the "Last Sure Water' sign, about 3,000 feet above sea level—not nearly as high as I'd like to be at this point.

Okay, so one hour. If I can finish in an hour, I'll be having a good day.

I study the trail and notice that there seem to be two ways to run this race. Most runners take the path of least resistance up the mountain, running along a zig-zag-zig path that goes from one low stone to another. They're actually running farther than 3.6 miles, but it doesn't feel so steep to them. A second group, much smaller based on the lack of wear in their path, takes the straightest possible line up the mountain. They bound, regardless of the trail or its obstacles, right up the sucker. I am taking the first tack, and wondering at what altitude you can start to blame thin air for poor athletic performance.

At 40 minutes I am approaching the innermost circle of hell. I think of my wife, safe and warm at home, maybe walking the dog after a nice Sunday breakfast. Oops. Bad idea to think of food just now. My thighs are on fire. No, they're past fire. Fire implies some organic matter that can be burned. There is nothing of the sort left in my legs. But at least I'm starting to pass the stunning views off to the right of the trail. And the wind is picking up, which means I'm closer to the top.

Then a group of four of the first runners to leave passes me—on their way down the mountain. They're not undergraduates. They're older than I am, and much, much faster. Here I was worried about kicking some 20-year-old butt and guys with less hair and better investment portfolios than me are the first ones down. I look up at them. They look down at me. They say nothing. No words of encouragement, not even a condescending "Looking good." The silence says it all. They are gazelles and cheetahs, and I am a pack mule. A wheezing, honking, nose-running, fogged-up-glasses pack mule.

More runners pass me, headed back to warmth and water and food. Hey, cut that out. Food is a bad thought. I'm walking as fast as I can up a set of granite, stair-like rises. Donovan passes, laughing. "Looking good," he says. "You're a mile from the top. Enjoy the view." Note to race spectators: don't ever tell runners how much farther they have to go. This is the worst kind of psychological trauma you can inflict. I know it's less than a mile, but somehow Donovan's words deflate me. Then the worried Nordie from the Ravine Lodge passes me. She's running back down themountain! She's got enough left to run down!The stamina and speed of a Pony Expresshorse! That punk!! The nerve of her beingnervous. "Hey, how's your story going, Mr. Writer?" she yells. "You're almost finished."

And with that I break above the tree line, the summit in sight, a gentle flat to cross, but a howling wind pulling me sideways. Now I'm a Chevy Suburban 4x4, too big to be practical but able to just grind wherever it wants to go. I try to stay on the path to help preserve the Alpine meadow on the mountain's top, but the wind keeps pushing me off. A very fit, very cold-looking guy with a big pack approaches me. "Are you okay?" he asks. I can't look that bad, can I? I tell him I'm fine and press on the last 100, the last 50, the last 20, the last 10 yards to the summit.

I slap the signpost, check my watch—58 minutes and change and head back down

There are no timers present. The guy who asked if I was okay was, it turns out, Ruff Patterson himself, who I guess grew tired of waiting for me, the last runner, and headed back down. Ruff will later tell me that the race was won by Chris Nice '74 in 37 minutes (well off the record of 35 minutes held by Adam Heaney '93). That's a kick in the "butt, but it also gives a body something to look forward to. He's a decade older than I am.

I trot along the trail above the treeline with a dispirited undergrad When we get into the woods we start to talk. He won't tell me his name, but he will tell me his time wasn't good. He talks more about studying—he's a premed philosophy major, for chrissakes—than about skiing, which in the big picture is a good sign but doesn't bode well for the upcoming season.

I press him for his time. He says he doesn't know. He won't admit it, but he and I both know that I beat this kid up the mountain. "How old are you? I ask. "Nineteen," he says. Nineteen. Nineteen. I have gray hairs that are 19. He doesn't know it, but this premed has made me the happiest 30-year-old on Mount Moosilauke.

But should I be happy? Do I deserve happiness on this, a day when my selfimage has run the gamut of the animal kingdom and the full spectrum of household machinery? On a day when I found out I wouldn't have been able to make one of Al Merrill's ski teams? The

answer is yes, because I learned some things: Any trail run you walk away from is a good one. Don't compare yourself to other people. Stay at home with your wife and have a nice breakfast.

And for God's sake, walk up the mountain and enjoy the view.

Coach Patterson

Ex-Coach Merrill

Ex-Coach Morton

The top—empty by the time the author got to it.

A former writer withFortune and M Inc.,Stephen Madden is editorand associate publisher ofCornell Magazine. Uponreturning home after theMoosilauke run he wasdiagnosed with bronchitis.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

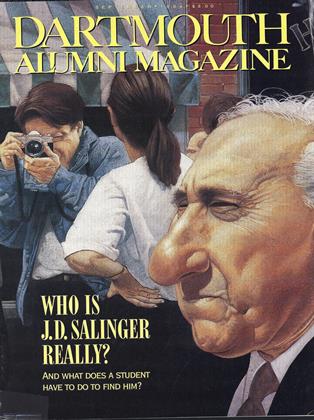

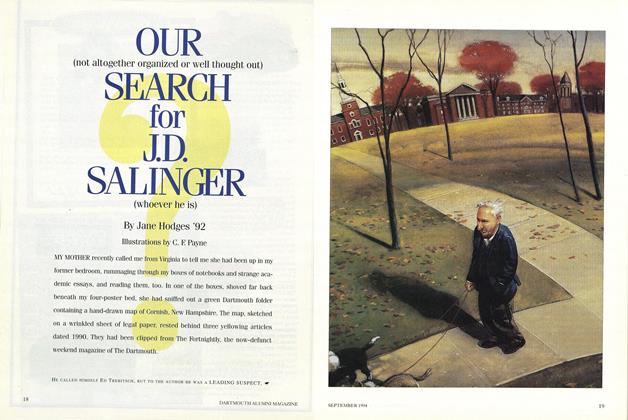

Cover StoryOUR SEARCH FOR J.D. SALINGER

September 1994 By Jane Hodges '92 -

Feature

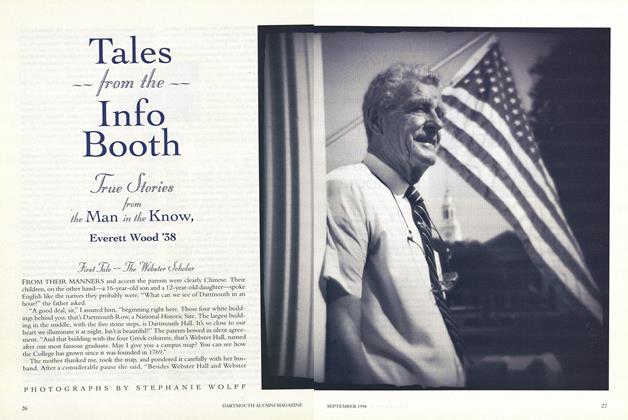

FeatureTales from the Info Booth

September 1994 -

Article

ArticleSEX AND THE DEVIL

September 1994 By Karen Endicott -

Article

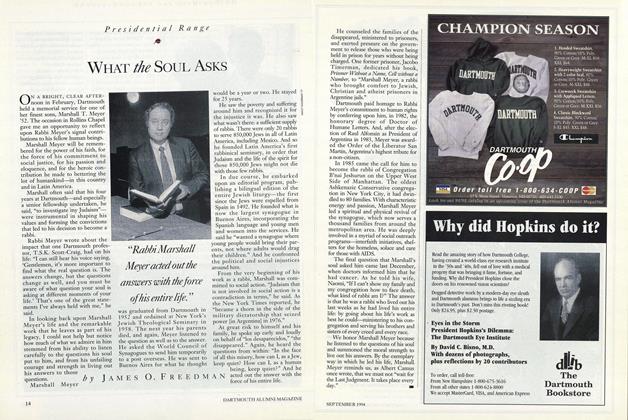

ArticleWhat the Soul Asks

September 1994 By James O. Freedman -

Class Notes

Class Notes1994

September 1994 By Nihad Farooq -

Class Notes

Class Notes1947

September 1994 By Ham Chase

Stephen Madden

Features

-

FEATURES

FEATURESThe Natural

MARCH | APRIL 2022 By DAVID HOLAHAN -

Cover Story

Cover StoryThe Dartmouth Disease

SEPTEMBER 1983 By George O'Connell -

Feature

FeatureAlumni News

Nov/Dec 2003 By John Kemp Lee '78, THE KOUROS GALLERY, NYC -

Feature

FeatureWhat It Was Was Grid-Graph

October 1980 By John R. Scotford Jr. -

Feature

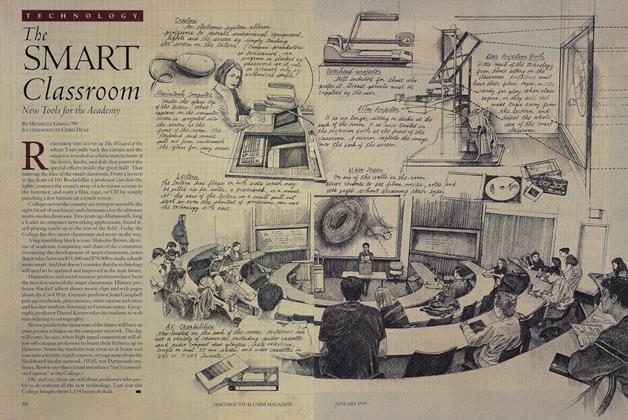

FeatureThe Smart Classroom

JANUARY 1999 By Michelle Gregg '99 -

Feature

FeatureThe Humanistic Pursuit of Values

MAY 1967 By ROBIN J. SCROGGS