People often ask why so many Dartmouth alumni end up in the film field and with distinction, at that. Is there, as they suspect, some mysterious Dartmouth-Hollywood connection, and, if so, how come?

To call attention to this notable phenomenon, the Dartmouth Film Society last year devoted its spring film series to movies in which alumni or the College environment played a significant part. Twenty-two feature films were included, and had we run more than one film per alumnus, there could have been ten times that many. The works covered a time span from D. W. Griffith's Way Down East (much of it filmed in the Hanover area in 1918 with some students used as extras) to a short documentary about the music department by Anne Hallager and Steve Oakes of the class of 1981.

Even with this limited retrospective, the suspicion about a Dartmouth-Hollywood connection seemed well-founded. But considering that Dartmouth is so remote from production centers and has never offered pre-professional training in film-making, why is there any connection at all?

One reason seems obvious: Dartmouth tried to bridge the gap between movies and education long before film study became academically fashionable. A notable example is the. Dartmouth Film Society itself. Launched by students under the direction of Blair Watson in 1949, the society became a prototype for organized film appreciation on campuses all over the country and undoubtedly contributed to a movie addiction that led many of those who graduated between 1950 and 1962 to choose careers in film.

But the connection was established, I think, even before World War I, when an enterprising young man, Walter Wanger '15, left Dartmouth before graduation to begin what was to be a very successful career as a producer in the infant movie industry. Wanger's rise to the top in Hollywood was followed by those of Arthur Hornblow '16 and Gene Markey '18, with the result that in an industry whose leaders were not exactly noted for their academic backgrounds, three outstanding producers were Dartmouth alumni.

Movie-going undergraduates in the thirties and forties were aware of the prestige of these men and impressed by it in a variety of ways-by the films they produced (Wanger's Stagecoach, Hornblow's Easy Living, and Markey's Wee Willie Winkie, to name a few) and perhaps even more by the beautiful women (Hedy Lamarr, Myrna Loy, and Joan Bennett) whom they married or courted often, or so it seemed, successively.

Some students, like Budd Schulberg '36, Hayes Goetz '37, Matthew Rapf'42, Jim Goldstone '53, David Picker '53, and myself (all sons of movie executives) were drawn to and possibly admitted to Dartmouth on the basis of recommendations from these distinguished alumni. Others, like Collier Young '30 (later the producer of television's Ironsides) and actors Bus Heidt '26, Charles Starrett '26, and Robert Ryan '32, were inevitably given boosts in their Hollywood careers by their Dartmouth connections.

But it was Wanger, most of all, who remained singularly devoted to the College and even tried to immortalize it on film in the übiquitous Ann Sheridan starrer, Winter Carnival (which lives on in Webster Hall as a midnight feature of this annual event).

It was Wanger also who helped to establish the first film course here in 1940 by arranging (and paying) for Professor W. Benfield Pressey of the English Department to visit Hollywood and "study" the industry and its methods for some months prior to teaching it.

And it was he, then president of the Motion Picture Academy of Arts and Sciences, who brought to Baker Library the Irving G. Thalberg memorial script library, which is still perhaps the best available collection of early screenplays in the country.

The prominence of Dartmouth producers may account for the fact that Dartmouth president Ernest Martin Hopkins was the principal speaker at the Academy Awards banquet on February 29, 1940, at which time he presented the prestigious Irving Thalberg Award to David O. Selznick, producer of Gone With the Wind.

Another principal source of the Dartmouth-movie syndrome was the old Nugget Theatre on West Wheelock Street. This unpretentious but loveable structure was in many ways the cultural center of our isolated community before the advent of television and subsequently of the Hopkins Center. Certainly it provided the principal diversion. As another distinguished alumnus, Sylvester "Pat" Weaver '30, former chairman of N.8.C., once said in explaining his early interest in the entertainment world, "In my day, Dartmouth men went to the movies more than most because there was nothing else to do."

Very true. One could spend a lot of time at the Nugget because the bill changed five or six times a week, there were three shows a day, and the admission was a quarter. Indeed, there were times when admission was "free," the result of a traditional student rush on the Nugget, to which only token resistance was offered by the head usher and Hanover police.

In my undergraduate days, we Nugget fans not only talked a lot about movies, we also talked back to them. A protracted love scene inevitably produced an audience chant calling on the hesitant lovers to "merge." Disapproval, all too frequent then as now, was expressed vociferously and, on occasion, physically, with a variety of hard objects being thrown at the screen.

When the punctured screen had to be replaced three times in 1936, manager Art Barwood discontinued the sale of five-cent apples in the lobby. For most students, it was a . sad day when the uproarious old Nugget burned down in 1944, and film showings were temporarily moved to the more dignified surroundings of Webster Hail.

In 1959, Beardsley Ruml '15, a life trustee of the College, proposed and agreed to fund a program of free daily films to supplement what students were learning in classes. This unusual plan, modified to a twice-weekly basis, continued for five years as "the free flicks" and was abandoned in 1965 when whatever educational value it may have had gave way to what one dean described as "behavior that bordered on the lunatic." The Film Society, which had been offering classics on a weekly basis, took up the slack with more frequent showings at its customary modest membership fee.

Most of what has already been described took place before film studies became a recognized part of the academic curriculum. It was a recognition not easily achieved. The new era had an auspicious beginning, however, in October 1965, when a conference on "Film Study in Higher Education," sponsored by the College in association with the American Council on Education, was held in the new Hopkins Center.

Now regarded as a landmark in the film study movement, this conference brought together the nation's leading film educators, critics, historians, and professionals and played a major role in stimulating the formation of the American Film Institute. The importance of film in contemporary culture was clearly established, but how or even whether it should be taught became a subject for entertaining, though sometimes acrimonious, debate. As critic Pauline Kael put it, "If you think the movies can't be killed, you underestimate the power of education."

At the time, Dartmouth had only one film course, which had been introduced the year before in response to a petition by more than 200 students but made feasible by the initiative of another distinguished movie alumnus, Orton Hicks '2l, who had given up an executive post with M.G.M. to become vice-president of the College. He found three-year financial support for the course from a foundation set up by his former boss, Nicholas M. Schenck of M.G.M. He found a teacher in the person of an old friend and movie exhibitor named Arthur L. Mayer, Harvard 'O8, whose academic credentials never would have been accepted by the English department without the enlightened persuasion of Professor Henry Williams. That Williams' maneuvers on Mayer's behalf were justified was borne out by the fact that Mayer (who got an honorary degree in 1970) was still teaching the course-History of Film-to over 200 students in 1976 when he celebrated his 90th birthday.

When the Drama Department (formerly part of English) was set up as a separate entity in 1968, film study went with it and was expanded to include a course in theory, writing, and production, taught once a year by the author of this article, who, like Mayer, had experience in the movie industry but no record as a teacher. Student demand led to additional courses related to film offered in the English, art, and comparative literature departments by Professors Gaylord, Robinson, and Oxenhandler, regular faculty members with interests and expertise in special aspects of movies. My own role was expanded to include courses in writing for the screen in documentary, and a freshman seminar in criticism-and I began to spend six months on campus and six months in New. York City working on my own film projects.

Then, in 1971, a grant from the President's Venture Fund made it possible to hire a full-time assistant professor in film (in addition to Mayer and me) and to give the expanded film study program a special status in the Drama Department, where we got invaluable support from the department chair, Professor Errol Hill, for a three-year trial period, during which I served as director on a part-time basis.

Today it is probably safe to say that film studies has passed the trial stages and, despite critic Kael's dire prophecies, we seem to have enhanced rather than killed the undergraduate's long-standing love affair with the movies. One reason is that we have continued to emphasize liberal arts and humanist needs for an understanding of creative work in film. Today, it is possible to do a concentration in film as a drama major. But the student electing such a major must fulfill course requirements also in ancient drama, Shakespeare, and contemporary drama and is urged to add courses in literature, art, music, and the social sciences. Of the twelve film courses now offered, only three involve hands-on production work (under the able instruction of professors David Parry and Ron Boehm), but, as other articles in this issue demonstrate, recent graduates have had remarkable success in a field where employment is contracting. Opportunities for film study are expanding. Last summer a dozen undergraduates received hands-on filmmaking experience as members of the cast and crew of David Thomson's feature film, White Lies, funded in part by the Drama Department and shot on location throughout New Hampshire.

It has always been the achievements of our alumni that gave Dartmouth its reputation as one of the best collegiate preparations for a career in film, but the active support of alumni has significantly increased the effectiveness of the way film subjects can be taught here. Director Joseph Losey '29 and writer Walter Bernstein '40 have each spent two terms here as visiting professors. Writer Stephen Geller '62 has just concluded a very successful summer term using Shakespeare as the basis for a screenwriting course. And others -such as director James Goldstone '53, writer Budd Schulberg '36, and actor Cliff Osman '59—have indicated an eagerness to do a term here when time permits.

The list of alumni who have come to the campus to show their films and talk to students reads like a who's who of the entertainment industry. In addition to those named above, there have been Buck Henry '52, Bob Rafaelson '54, Don Hyatt '50, Grant Tinker '47, Vincent Canby '45, Roger Brown '57, Frank Gilroy '50, David Picker '53, Peter Werner '6B, Michael Phillips '65, Charles Starrett '26, Ralph Steiner '21, and many others. A student once wrote in his journal: "I'm still impressed that people like this are actually taking the time to come to Dartmouth and talk to me about their films. It's great. The most valuable learning experience I've ever had."

Alumni visitors, in turn, are grateful for the opportunity to work with students, and once they get past the inevitable first question-"How do I go about getting a job?"-they find the contact stimulating and a source of new values and insights related to their own work.

So there is indeed a Dartmouth-Hollywood connection, one that continues, as it has for generations, to promote high standards of excellence for students and professionals alike.

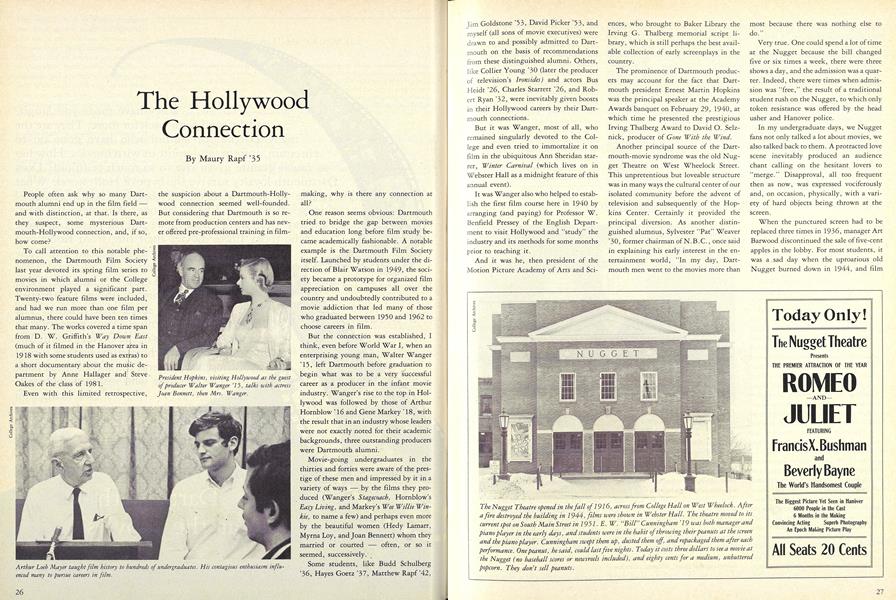

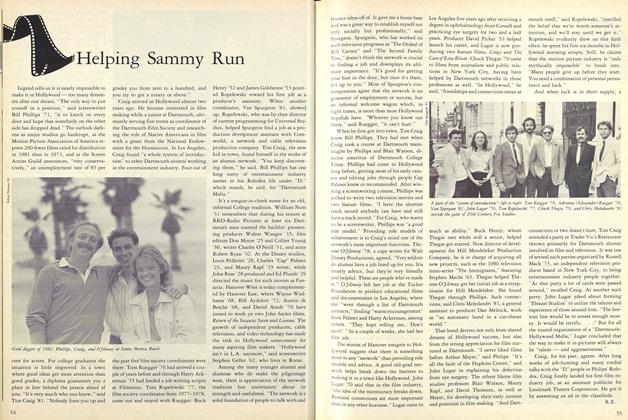

President Hopkins, visiting Hollywood as the guestof producer Walter Wanger '15, talks with actressJoan Bennett, then Mrs. Wanger.

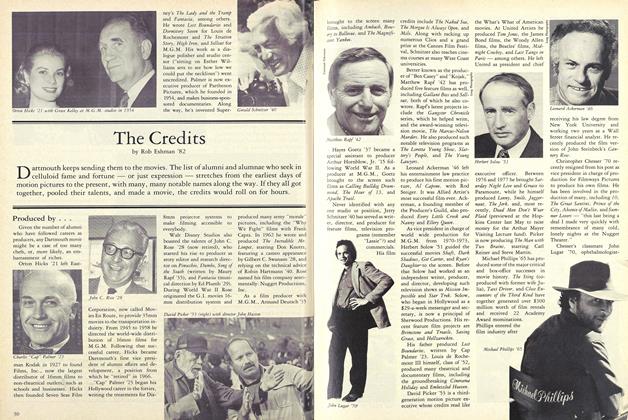

Arthur Loeb Mayer taught film history to hundreds of undergraduates. His contagious enthusiasm influenced many to pursue careers in film.

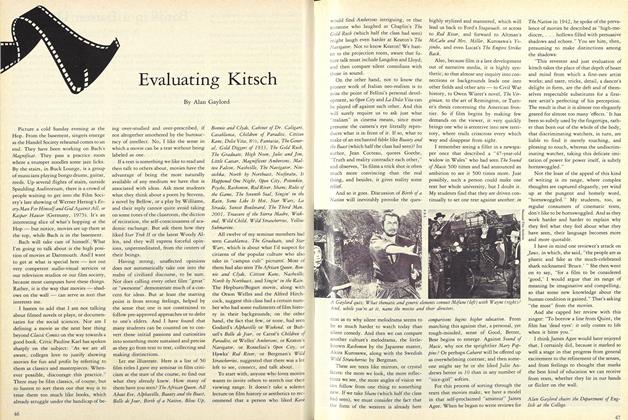

The Nugget Theatre opened in the fall of 1916, across from. College Hall on West Wheelock. Afteraa fire destroyed the building in 1944, films were shown in Webster Hall. The theatre moved to itscurrent spot on South Main Street in 1951. E. W. "Bill" Cunningham 19 was both manager andpiano player in the early days, and students were in the habit of throwing their peanuts at the screenand the piano player. Cunningham swept them up, dusted them off, and repackaged them after eachperformance. One peanut, he said, could last five nights. Today it costs three dollars to see a movie atthe Nugget (no baseball scores or newsreels included), and eighty cents for a medium, unbutteredpopcorn. They don't sell peanuts.

Voices of experience: Professor Maury Rapf'35 (left) introduces N.B.C. Chairman Grant Tinker '47 andMary Tyler Moore to a film studies class.

Maury Rapf '35, adjunct professor of drama andlongtime director of film studies at the College, ap-pears in our "Credits." His encouragement, advice,and cooperation were a great help in the preparationof this special issue.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureThe Credits

November 1982 By Rob Eshman '82 -

Feature

FeatureEvaluating Kitsch

November 1982 By Alan Gaylord -

Feature

FeatureHelping Sammy Run

November 1982 -

Feature

FeatureThe Camera Man

November 1982 By James Farley '42 -

Feature

FeatureThe West That Wasn't

November 1982 By R.E. -

Feature

FeatureBards in a Barren Desert

November 1982 By Stephen Geller '62

Maury Rapf '35

Features

-

Feature

FeatureGlee Club Heads West This Spring

March 1956 -

Feature

FeatureSOUTH END STORY

APRIL 1965 -

Feature

FeatureTwo Student Projects for Peace

May 1961 By D.E.O. -

Feature

FeatureOf Peaceful Men and Violent Ideas

DECEMBER 1968 By DEAN THADDEUS SEYMOUR -

Cover Story

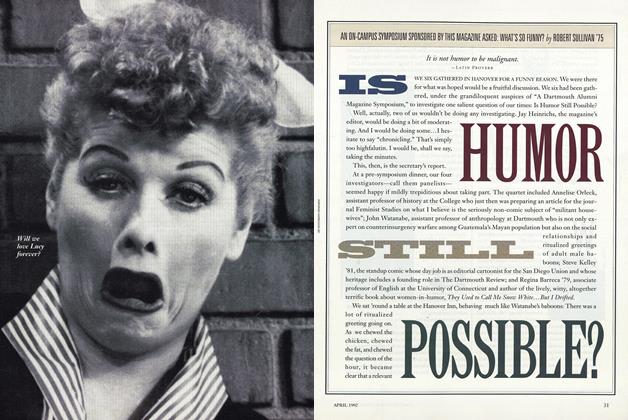

Cover StoryIS HUMOR STILL POSSIBLE?

APRIL 1992 By ROBERT SULLIVAN '75 -

Feature

FeatureThe Comprehensive Classroom:

JANUARY/FEBRUARY 1986 By Roger D. Masters and William C. Scott