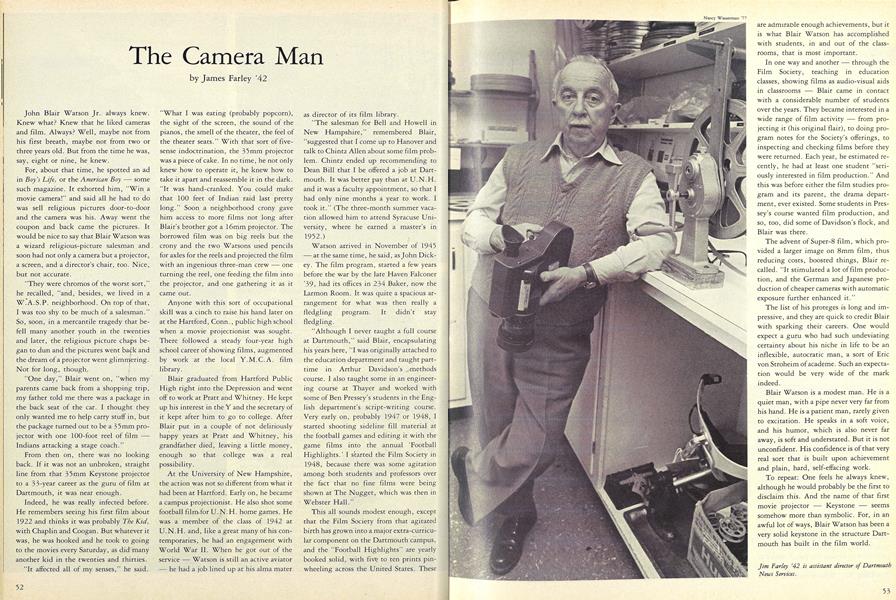

John Blair Watson Jr. always knew. Knew what? Knew that he liked cameras and film. Always? Well, maybe not from his first breath, maybe not from two or three years old. But from the time he was, say, eight or nine, he knew.

For, about that time, he spotted an ad in Boy's Life, or the American Boy some such magazine. It exhorted him, "Win a movie camera!" and said all he had to do was sell religious pictures door-to-door and the camera was his. Away went the coupon and back came the pictures. It would be nice to say that Blair Watson was a wizard religious-picture salesman and soon had not only a camera but a projector, a screen, and a director's chair, too. Nice, but not accurate.

"They were chromos of the worst sort," he recalled, "and, besides, we lived in a W.A.S.P. neighborhood. On top of that, I was too shy to be much of a salesman." So, soon, in a mercantile tragedy that befell many another youth in the twenties and later, the religious picture chaps began to dun and the pictures went back and the dream of a projector went glimmering. Not for long, though.

"One day," Blair went on, "when my parents came back from a shopping trip, my father told me there was a package in the back seat of the car. I thought they only wanted me to help carry stuff in, but the package turned out to be a 35mm projector with one 100-foot reel of film Indians attacking a stage coach."

From then on, there was no looking back. If it was not an unbroken, straight line from that 35mm Keystone projector to a 33-year career as the guru of film at Dartmouth, it was near enough.

Indeed, he was really infected before. He remembers seeing his first film about 1922 and thinks it was probably The Kid, with Chaplin and Coogan. But whatever it was, he was hooked and he took to going to the movies every Saturday, as did many another kid in the twenties and thirties.

"It affected all of my senses," he said.

"What I was eating (probably popcorn), the sight of the screen, the sound of the pianos, the smell of the theater, the feel of the theater seats." With that sort of fivesense indoctrination, the 35mm projector was a piece of cake. In no time, he not only knew how to operate it, he knew how to take it apart and reassemble it in the dark. "It was hand-cranked. You could make that 100 feet of Indian raid last pretty long." Soon a neighborhood crony gave him access to more films not long after Blair's brother got a 16mm projector. The borrowed film was on big reels but the crony and the two Watsons used pencils for axles for the reels and projected the film with an ingenious three-man crew one turning the reel, one feeding the film into the projector, and one gathering it as it came out.

Anyone with this sort of occupational skill was a cinch to raise his hand later on at the Hartford, Conn., public high school when a movie projectionist was sought. There followed a steady four-year high school career of showing films, augmented by work at the local Y.M.C.A. film library.

Blair graduated from Hartford Public High right into the Depression and went off to work at Pratt and Whitney. He kept up his interest in the Y and the secretary of it kept after him to go to college. After Blair put in a couple of not deliriously happy years at Pratt and Whitney, his grandfather died, leaving a little money, enough so that college was a real possibility.

At the University of New Hampshire, the action was not so different from what it had been at Hartford. Early on, he became a campus projectionist. He also shot some football film for U.N.H. home games. He was a member of the class of 1942 at U.N.H. and, like a great many of his contemporaries, he had an engagement with World War II. When he got out of the service-Watson is still an active aviator -he had a job lined up at his alma mater as direccor of its film library

"The salesman for Bell and Howell in New Hampshire," remembered Blair, "suggested that I come up to Hanover and talk to Chintz Allen about some film problem. Chintz ended up recommending to Dean Bill that I be offered a job at Dartmouth. It was better pay than at U.N.H. and it was a faculty appointment, so that I had only nine months a year to work. I took it." (The three-month summer vacation allowed him to attend Syracuse University, where he earned a master's in 1952.)

Watson arrived in November of 1945 -at the same time, he said, as John Dickey. The film program, started a few years before the war by the late Haven Falconer '39, had its offices in 234 Baker, now the Larmon Room. It was quite a spacious arrangement for what was then really a fledgling program. It didn't stay fledgling.

"Although I never taught a full course at Dartmouth," said Blair, encapsulating his years here, "I was originally attached to the education department and taught parttime in Arthur Davidson's methods course. I also taught some in an engineering course at Thayer and worked with some of Ben Pressey's students in the English department's script-writing course. Very early on, probably 1947 or 1948, I started shooting sideline fill material at the football games and editing it with the game films into the annual 'Football Highlights.' I started the Film Society in 1948, because there was some agitation among both students and professors over the fact that no fine films were being shown at The Nugget, which was then in Webster Hall."

This all sounds modest enough, except that the Film Society from that agitated birth has grown into a major extra-curricular component on the Dartmouth campus, and the "Football Highlights" are yearly booked solid, with fivt to ten prints pinwheeling across the United States. These are admirable enough achievements, but it is what Blair Watson has accomplished with students, in and out of the

classrooms, that is most important. In one way and another through the Film Society, teaching in education classes, showing films as audio-visual aids in classrooms-Blair came in contact with a considerable number of students over the years. They became interested in a wide range of film activity-from projecting it (his original flair), to doing program notes for the Society's offerings, to inspecting and checking films before they were returned. Each year, he estimated recently, he had at least one student "seriously interested in film production." And this was before either the film studies program and its parent, the drama department, ever existed. Some students in Pressey's course wanted film production, and so, too, did some of Davidson's flock, and Blair was there.

The advent of Super-8 film, which provided a larger image on Bmm film, thus reducing costs, boosted things, Blair recalled. "It stimulated a lot of film production, and the German and Japanese production of cheaper cameras with automatic exposure further enhanced it."

The list of his proteges is long and impressive, and they are quick to credit Blair with sparking their careers. One would expect a guru who had such undeviating certainty about his niche in life to be an inflexible, autocratic man, a sort of Eric von Stroheim of academe. Such an expectation would be very wide of the mark indeed.

Blair Watson is a modest man. He is a quiet man, with a pipe never very far from his hand. He is a patient man, rarely given to excitation. He speaks in a soft voice, and his humor, which is also never far away, is soft and understated. But it is not unconfident. His confidence is of that very real sort that is built upon achievement and plain, hard, self-effacing work.

To repeat: One feels he always knew, although he would probably be the first to disclaim this. And the name of that first

movie projector Keystone seems somehow more than symbolic. For, in an awful lot of ways, Blair Watson has been a very solid keystone in the structure Dartmouth has built in the film world.

Jim Farley '42 is assistant director of DartmouthNews Services.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

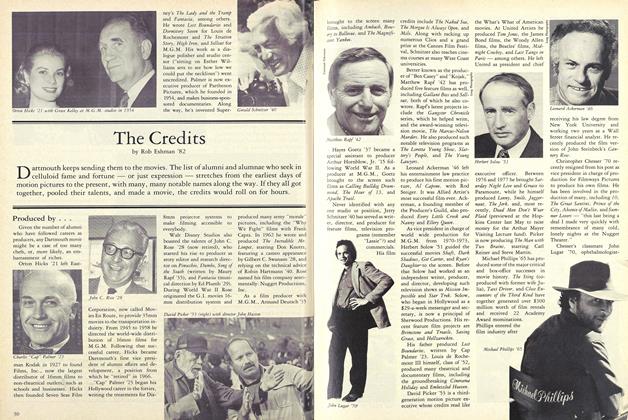

FeatureThe Credits

November 1982 By Rob Eshman '82 -

Feature

FeatureThe Hollywood Connection

November 1982 By Maury Rapf '35 -

Feature

FeatureEvaluating Kitsch

November 1982 By Alan Gaylord -

Feature

FeatureHelping Sammy Run

November 1982 -

Feature

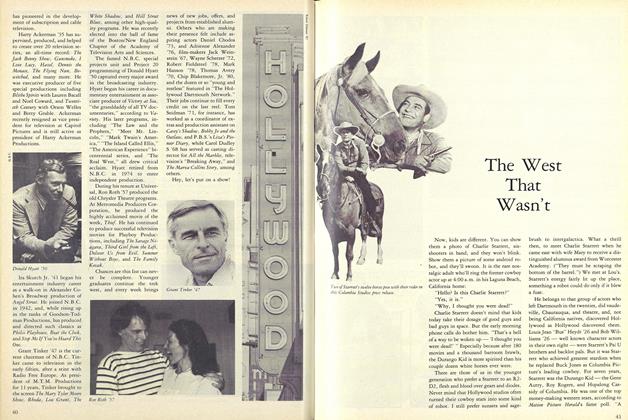

FeatureThe West That Wasn't

November 1982 By R.E. -

Feature

FeatureBards in a Barren Desert

November 1982 By Stephen Geller '62

Features

-

Feature

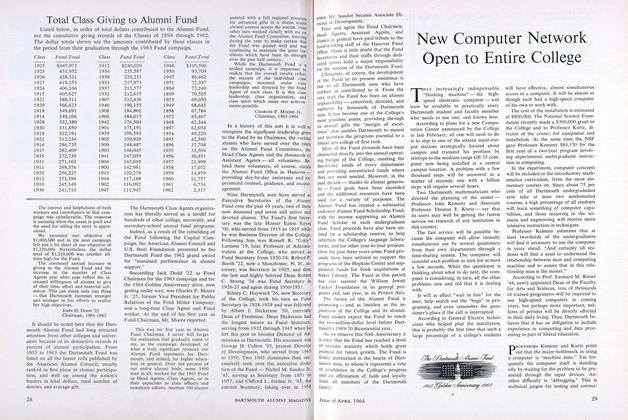

FeatureNew Computer Network Open to Entire College

APRIL 1964 -

Feature

FeatureA New Strategy of Liberal Learning

MAY 1964 -

Feature

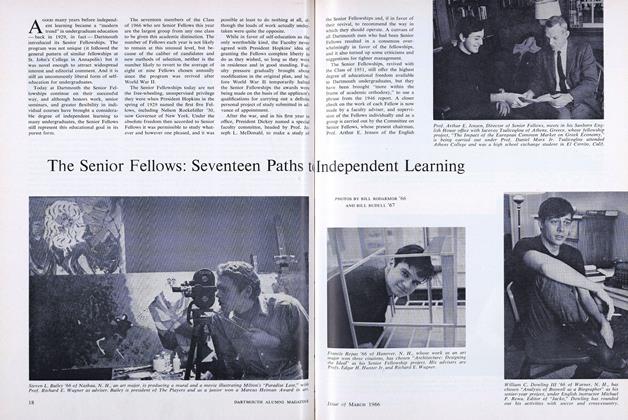

FeatureThe Senior Fellows: Seventeen Paths to Independent learning

MARCH 1966 -

Feature

FeatureAnd More

April 1975 -

Feature

FeatureCue the Millennium

NOVEMBER 1996 -

Feature

FeatureFinal Assembly

October 1951 By SIR HAROLD CACCIA