"Dartmouth College doesn't have to have a Tucker Foundation," says Fred Berthold. "No other college anywhere else has anything like it. But at this crossroads, the College should either reaffirm it clear and strong or abandon it."

Thirty-three years ago, Berthold became the first dean of the Tucker Foundation, and this year he has been recalled to serve as acting dean while the College locates a permanent replacement for Warner Traynham, who last year left the deanship to return to parish work. "I said no at first," remarks Berthold, who looks tired. "I am in the middle of a book and I have done my bit. I enjoy my teaching. But then I realized that this interim thing needs someone who knows the history and the original concept of the foundation. So I decided I ought to do it."

The Tucker Foundation was the brainchild of President John Sloan Dickey, as Berthold explains: "Since the time of President Tucker, none of Dartmouth's presidents has been specifically trained in the analysis of religious or moral problems, and President Dickey felt that loss. There were no longer compulsory courses in religion, chapel was no longer required, and Dickey envisioned the Tucker Foundation as restoring institutionally that "sort of Tucker-exemplified influence."

The Trustees bought the idea and in 1951 voted in such a foundation. It was to be an independent endowment "for the specific purpose of supporting and furthering in all ways and in all areas the moral and spiritual work of the College." They prefaced their mandate with a clarion declaration of faith in the two-fold, black-and-white nature of existence: "This moral and spiritual purpose [of the College] springs from a belief in the existence of good and evil, from faith in the ability of men to choose between them, and a sense of duty to advance the good."

It is not clear what definitions of good and evil the Trustees had in mind, nor which form of religion those definitions were drawn from, and that may have had something to do with the fact that the Tucker Foundation's efforts to advance the good have been plagued since birth by uncertainty. Berthold's formulation of the foundation's genesis is telling: "The foundation was somehow to represent, influence, and stimulate the College's commitment to moral spiritual matters. Sometimes the word religious was used." Moral spiritual religious. Are they all one and the same? Which morality, whose spirituality, and what religion? The questions proliferate, and they are hard ones.

A committee advisory to the foundation was established in 1952 and met for the next four years trying to figure out what form the foundation that was to memorialize President Tucker should take and who should be its first dean. The minutes of that committee record that what was wanted was a religious leader. It was hoped that the influence of the foundation would be carried largely through preaching at Rollins Chapel and the immediate task of the committee was to find a preaching dean good enough to become a rallying point. The committee aimed high, trying to interest such high-level clergy as Bishop Pike of the Cathedral of St. John the Divine in Washington. But none of the country's religious luminaries was, as Berthold puts it, "detachable from his job." In the end, the committee recommended an in-house candidate, and Professor of Religion Fred Berthold was invited to become the first dean.

Then the long, hard struggle to reinstitute religion at Dartmouth began. "We continued to try chapel services," recalls Berthold, "and six times a year at Rollins we had a union service together with all the local protestant churches and the Glee Club and a prominent speaker. We tried it all kinds of different ways daily chapel, weekly vespers, everything. The only service that drew much attendance was the union service. The townspeople came to that. The utter and bitter end of this all was a vespers service in May, when John Dickey was the speaker, and he and I were the only ones who came."

Berthold returned to teaching in 1963, and the Reverend Richard Uns-worth became the foundation's second dean. "Richard was a marvelous preacher," recalls Berthold. "Rollins Chapel was his main interest too; and it was a colossal fizzle under him as well,"

Perhaps the foundation was miscast in the beginning. It is true that William Jewett Tucker was the last,of Dartmouth's preacher presidents. But it is also true that he was the least doctrinal of them "religiously very liberal" as Berthold puts it. He was also one of the last people in the country to be tried on charges of heresy (in connection with Darwinian ideas). Berthold explains that for Tucker, "Theology was always a little bit mysterious and non-essential. He believed that God was loving and would not damn anyone to hell. That smacked too much of Catholicism to puritanical New Engenders. After all, the Dartmouth of the 1890s was rigidly Calvinistic. The faculty was hidebound, anti-science, and convinced that Darwin was leading people straight to hell."

Tucker was certainly a charismatic speaker, and he personally addressed chapel at the College every Sunday at vespers and was much liked for it. But his importance to Dartmouth went far beyond that in a decidedly secular direction. "Without him, the College might not have survived," says Berthold. "It was in sad shape in 1893, when he accepted the presidency. There were only four or five hundred students, most of them from New England; there were 17 professors, all of them desperately overworked; and the entire annual budget was $52,000. Tucker gambled. He persuaded the Trustees to borrow money from the government at five percent; he built up the faculty; he hired scientists; he built laboratories; and he sought students from across the country." In this diversifying process, Tucker did not repudiate the College's Christian conception; but, as Berthold explains, he did broaden it "so as to make it identical with ethical and moral concerns." Berthold credits Tucker with having brought Dartmouth College into the modern era.

It may be significant that over its long history, the most clearly successful work of the Tucker Foundation has been secular. The heyday of the foundation those years when it was most visible and most active, most creative, and most solvent (to the impressive tune of a million-dollar budget) was apparently the span of time during which it was headed by the one lay dean of its history, Charles Dey. "Doc" Dey was an active Episcopalian but neither preacher nor professor of religion, and under him the foundation flourished as a service and educational organization.

"He was very inventive and very clever at getting money (though most of it was soft)/' Berthold explains. During Dey's tenure 1967 to 1974 were born the College's ABC program, Outward Bound at Dartmouth, the Jersey City and Kicking Horse Reservation internships, and the internship at Compton, California, in the Watts area. Local service efforts were expanded, too, with programs such as Big Brother and Big Sister for area young sters. (For such projects, the long-active Dartmouth Christian Union was both a model and a jumping-off point.)

But Dey's efforts hit a snag, one that Berthold guesses may have led in the end to his resigning the deanship. "The one area that didn't go well for him was the relationship with the faculty. It was a big issue. He thought a lot of interns should get academic credit should have their service work in Jersey City or Kicking Horse or Watts monitored, should keep a journal, read certain books, write reports on their experiences, and get academic credit through the Department of Education. Otherwise, he felt, students would have neither the time nor the money to do such internships. At first the faculty went along, then increasingly it became suspicious, until finally it voted an end to the credit. After that, the programs' popularity declined. Dey came to feel that the faculty were too rigid and unappreciative of the kind of learning that comes through personal experience."

Berthold's own reflections on this aspect of American higher education lend some credence to Dey's objections: "In those institutions that are extremely competitive in hiring the 'best' faculty of professionals active scholars in the field, quality is measured in publication. There tends to be in American higher education of that sort a suspicion about experiential nonrational learning. Nonetheless, some of the most important learning that ever took place at the Tucker Foundation occurred on internships. Jersey City, for example, often had an enormous impact on students' lives. Often it provided them with directions for further study and exposed them to new and often enlightening attitudes. Many scholars say that that's all well and good, but it's not education. The effect of such aloofness from experiential learning is a bifurcation. I understand how moral principles can be approached rationally but to become a moral person involves motivation, involves the emotions. To know the good is not necessarily to do the good. You've got to get the old feelings stirred up to get the energy and sometimes the courage to do what the mind tells you it would be good to do."

Dean Dey's successor Paul Rahmeier also found the faculty a stumbling block. An ordained Church of Christ minister with a doctorate in the philosophy of religion, Rahmeier requested adjunct faculty status in the Department of Religion. He was refused, according to Berthold, on the grounds that he was not committed to the objective academic study of religion but to the fostering of religious life

"and to have on the faculty a person whose primary occupation was clergyman was felt to be inappropriate and confusing."

The matter of status was also a bone of contention between the administration and the next dean, Warner Traynham, an ordained Episcopalian minister. President Kemeny decided that instead of reporting directly to him, the dean of the Tucker Foundation should report instead to the provost of the College. Then, when the position of provost was discontinued, the dean in effect descended another notch and found himself reporting to the dean of the College. "Having the dean of the Tucker Foundation report to another dean gives the wrong signal," explains Berthold. "It suggests the foundation is concerned only with student life, whereas the original concept of the foundation was institution-wide." Certainly that was Dickey's sense, and he once described the deanship as "a position of pervasive scope, . . . the occupant of which will have the campus as well as the chapel for his province."

This complex issue of status, involving both faculty relations and administrative pecking order, seems to Berthold "one of the trickiest things" about the foundation at present: "The Tucker foundation won't have maximum impact on campus unless it can work closely with the faculty. Perhaps the dean should enjoy some sort of faculty status." But, Berthold admits, he doesn't know exactly how that could be achieved.

From his long association with the foundation, Berthold has come up with some strong recommendations regarding its future. They probably cost him some midnight oil: "One of my recommendations is that Dartmouth College and the Tucker Foundation as its representative should as far as possible cease sponsoring worship services or education in any specific religious tradition." The only exceptions Berthold makes are temporary: "At the present time, the Jewish community is not strong enough to hire a full-time rabbi, and since the College has a sizeable Jewish population, we should continue to subsidize those worship services. We should also consider subsidizing worship in the black tradition, for similar pragmatic reasons."

Berthold cites as a model for future efforts the foundation's recent and highly successful Central America Information Committee, which tapped local as well as outside resources, including faculty, to mount a term's worth of interwoven lectures, courses, demonstrations, and exhibits designed to explore the immediate and urgent questions raised by this country's military presence in Central America.

"Along the same lines, I would like to bring in some people to help us understand racism better than we do at Dartmouth," he explains. "The foundation has some resources of its own, and we can say to the faculty, 'Shouldn't there be more emphasis on this issue, or this topic?' If the faculty agree, there need be no antagonism between our efforts and theirs, and it should be okay to plan such programs."

Berthold would also like to see the foundation work more closely with the dean of the College: "He gets involved in all the trouble spots on campus fraternity life, sexism, alcoholism, and just plain student loneliness. We should work together on them meet once a week, perhaps. I'm not suggesting we report to the dean, but that the two of us work as colleagues."

Trustee reaffirmation of the Tucker Foundation as an institution-wide effort has been made, according to Berthold, and the foundation is here to stay for the foreseeable future. Its budget like everybody else's is down (not so much because the College has pulled any financial rugs from under it, which it hasn't, but because the soft moneys it once enjoyed have dried up). President McLaughlin's plans for it involve a firm summons back to home base. "McLaughlin's view is that the foundation should spend more of its efforts on campus," explains Berthold. "He is down on Jersey City and similar efforts, feeling there is not enough feedback into Dartmouth to justify them." Many of Berthold's recommendations regarding the foundation are apparently going to be accepted, though the tricky business of its relationship with the faculty is still unresolved.

"A chaplaincy that got out of hand," is the way Warner Traynham, never a man to mince words, once described his position as dean of the Tucker Foundation. "The foundation," said Traynham, "is concerned with questions of institutional responsibility, is a clearing house for issues of moral concern brought to its attention, and acts as a gadfly in keeping these issues before the College." That may turn out to be a valuable ongoing description. Born as a rather narrowly religious enterprise, the foundation may, irrepressibly, have been changing right along with the changing times. The next few years in the life of the William Jewett Tucker Foundation should prove particularly interesting.

"Do not expect that you will make any lasting or very strong impression on the world through intellectual power without the use of an equal amount of conscience and heart." William Jewett Tucker

"To know the good is not necessarily to do the good. You've got to get the old feelings stirred up to get the energy and sometimes the courage to do what the mind tells you it would be good to do." Fred Berthold

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeaturePsycho-Social Dynamics and the Prospects for Mankind

December 1983 By Charles E. Osgood '39 -

Feature

FeatureMaris Bryant Pierce: A Seneca Chief at Dartmouth

December 1983 By Howard A. Vernon -

Feature

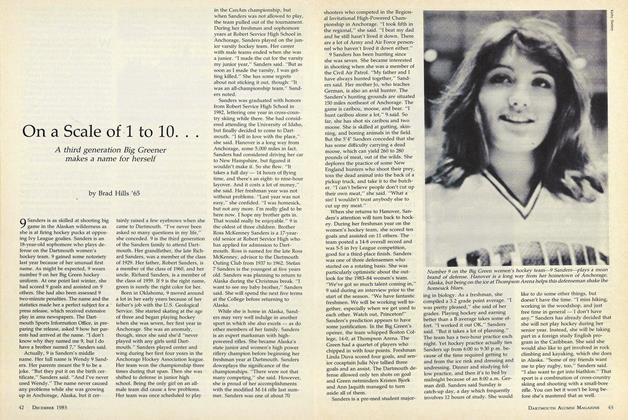

FeatureOn a Scale of 1 to 10...

December 1983 By Brad Hills '65 -

Feature

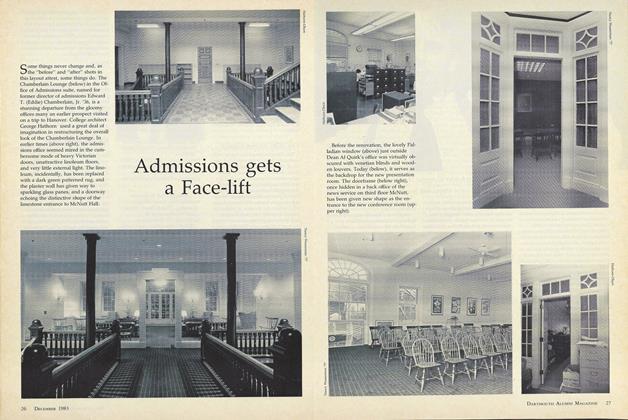

FeatureAdmissions gets a Face-lift

December 1983 By Nancy Wasserman -

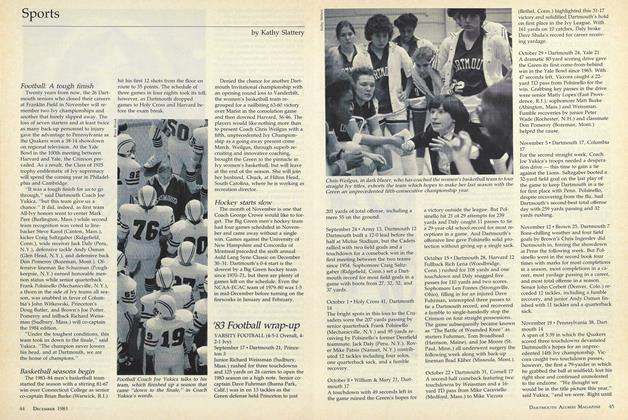

Sports

SportsSports

December 1983 By Kathy Slattery -

Article

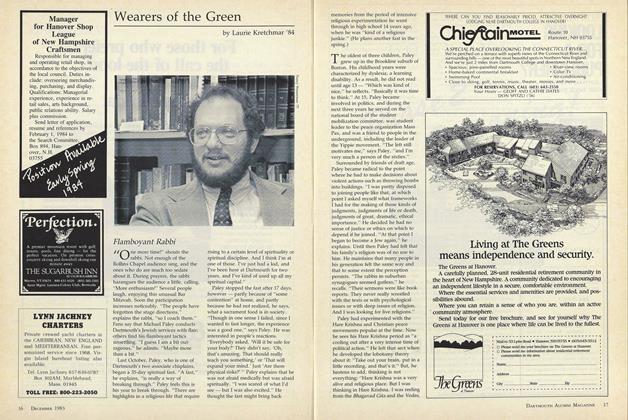

ArticleFlamboyant Rabbi

December 1983 By Laurie Kretchmar '84

Shelby Grantham

-

Feature

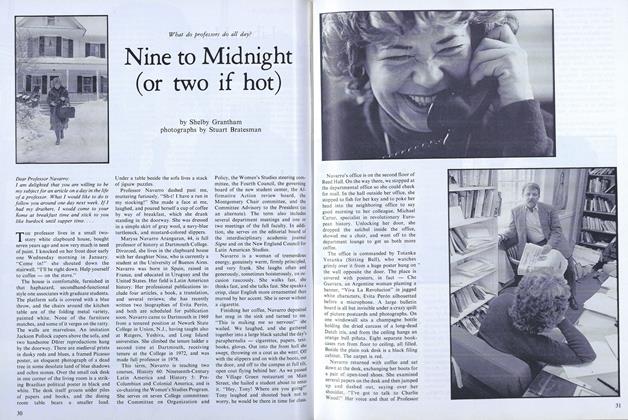

FeatureNine to Midnight (or two if hot)

March 1979 By Shelby Grantham -

Feature

FeatureThe Wooden Shoe: A Commune

May 1979 By Shelby Grantham -

Feature

FeatureHigh Tech Crisis

JUNE 1983 By Shelby Grantham -

Feature

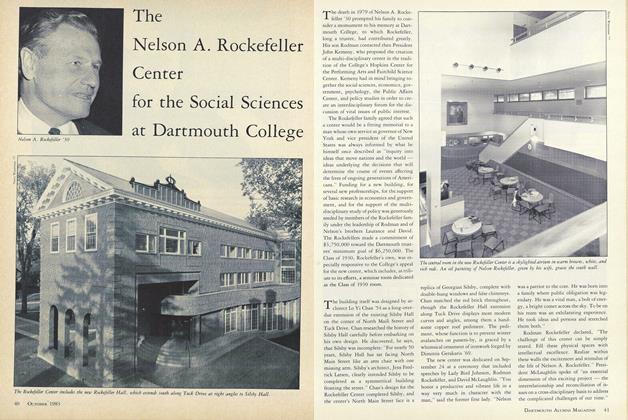

FeatureThe Nelson A. Rockefeller Center for the Social Sciences at Dartmouth College

OCTOBER, 1908 By Shelby Grantham -

Feature

FeatureThe Attraction of Peanuts

JUNE/JULY 1984 By Shelby Grantham -

Feature

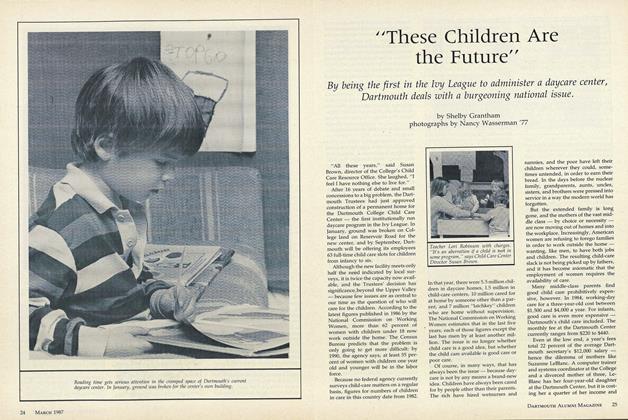

Feature"These Children Are the Future"

MARCH • 1987 By Shelby Grantham

Features

-

Feature

FeatureNew Faculty Faces

October 1954 -

Cover Story

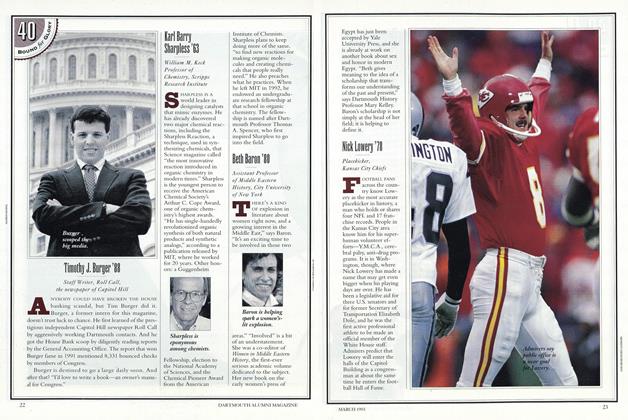

Cover StoryTimothy J. Burger '88

March 1993 -

COVER STORY

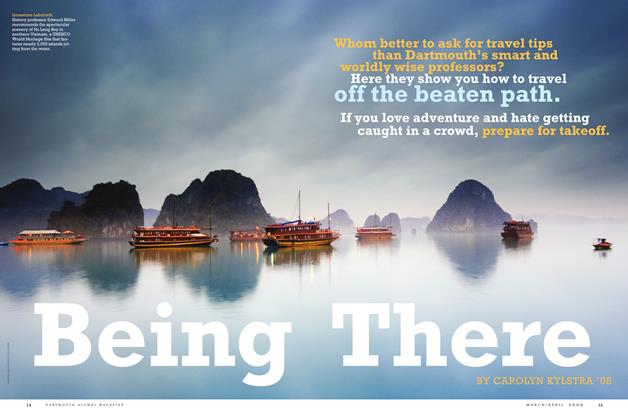

COVER STORYBeing There

Mar/Apr 2009 By Carolyn Kylstra ’08 -

Feature

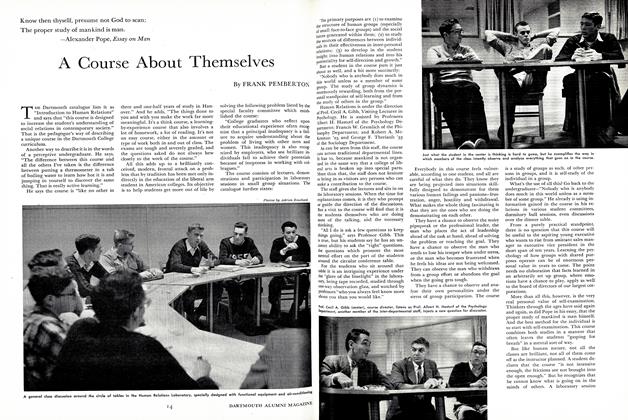

FeatureA Course About Themselves

January 1954 By FRANK PEMBERTON -

Feature

FeatureAn Irresistible Pull

April 1995 By Jay Paris -

Feature

FeatureZen and the Art of Corporate Maintenance

JANUARY/FEBRUARY 1985 By Shelby Grantham