ON rare occasions, Matthew Wysocki can be found in his office. He is much more often found in his "outer office"-

the Hopkins Center snack bar. Wysocki's Upper Jewett corridor office is neither small nor remote; it is just that it is all filled up.

"I never throw anything away," Wysocki explains, opening the door to his fantasy world. No fan of cinder-block architecture, Wysocki has transformed his piece of the Hop with a startling array of collectibles: columns from the old Howe Library, toys, miscellaneous pieces from demolition sites as far distant as Massachusetts and France, innumerable plants (ineluding a huge Boston fern that screens the office from passers-by) prints, postcards, drawings, and stacks of correspondence reputedly held up by a desk.

Wysocki gleefully relates how, a years back, a wealthy woman inquired about buying his office intact. He found the offer amusing, but refused: It would have totally depleted me. I would have had to start all over again."

He started on his office in 1966, when he came to Dartmouth from Cooper Union in New York, where he had been associate professor and director of the evening school. His task here was to take in hand the College's fledgling studio program at the young Hopkins Center. In the past 16 years, Wysocki has developed what is now called Visual Studies into a rigorous program of design, color, drawing, and art history with a final concentration in an area of the student's choice, such as painting, sculpture, or architecture. Each year the department graduates 20 to 25 students. Most go on to graduate school or become practicing artists. Many have their pick of the finest art and architecture schools in the country.

As one of the last of the Hop's founding fathers young enough still to be employed, Wysocki remains the department's chief administrator whether or not he is chairing it. He personally approves all Visual Studies course cards for students and course plans for all majors. Many students curse Wysocki's control of the department and the long hours he requires them to spend in the studio, but they also appreciate the quality of the program he has developed and the resources he has made available. One of those is the small but exceptionally fine faculty of practicing professionals Wysocki has pulled together.

But his major achievement may be development of the College's artist-in-residence program. "The idea of an artist-in-residence," as Wysocki tells it, "actually began in the thirties with Orozco painting his murals. Then for a period of 20 years, there was Paul Sample, who maintained a studio in Carpenter Hall." Today, the artist-in-residence program sponsors a different artist each term, which allows numerous styles and concentrations to be represented within a "student's four-year stay. The program is a tremendous resource for all students," Wysocki explains. Mainstream artists are brought to campus, where it is easy for any student to meet them and art majors can work with them. Recent artists-in-residence have included graphic designer John Alcorn, painter Richard Anuszkiewicz, photo-realist painter Tom Blackwell, photographer Marie Cosindas, print maker Jim Dine, English painter R. B. Kitjai, photographer Walker Evans, and sculptor Richard Stankiewicz. Most of the artists are known Personally by Wysocki through his connections at city galleries, at Cooper Union, and at Yale, where he himself did graduate work with Josef Albers.

As his office suggests, Wysocki is not only a man of connections but also of collections folk art, original drawings, scrimshaw, Americana, Santa Clauses, photographs (including his own archives chronicling the American Dance Festival), and toys. Wysocki's passion for collecting began when he was an undergraduate, and he is happy to assist today's undergraduates in beginning collections of their own. Frequently he travels with them to show them collections of interest.

Best known and appreciated is Wysocki's toy collection, which numbers close to 3,000 pieces and has frequently been featured on national television. Wysocki's fascination with toys stems from their universal appeal and his own interest in Americana. "They reflect the decade and century from which they come," he states. "From them we can pinpoint different times, attitudes, social conditions, and customs."

Wysocki's toy collection includes a wide variety, from battalions of antique lead soldiers and myriads of puzzles to modern-day computer games, robots, and rockets. He points out that our current space-age toys will become tomorrow's antiques. Many of the older toys have come from yard sales, auctions, flea markets, and second-hand shops, where Wysocki has become such a familiar figure that local vendors set things aside for him - and, he concedes, "raise the price a bit."

Unfortunately, the size of Wysocki's collection has far exceeded his toy chest - as well as his office, attic, a garage, and living area. Therefore, much of the collection stays boxed up in warehouses unless it is being loaned out for an exhibit such as the one planned for this December at the Hopkins Center.

As more and more museums request the use of his collection, Wysocki has recognized the need to begin cataloguing the toys. But doing so is still something he just dreams about. He also talks of the need to print his dance photographs and work at his own photography. But for the time being, Wysocki will most likely be wrestling with the challenges of the new Hood Museum - better facilities, more gallery space, and what he called the problem of "getting Visual Studies even better."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

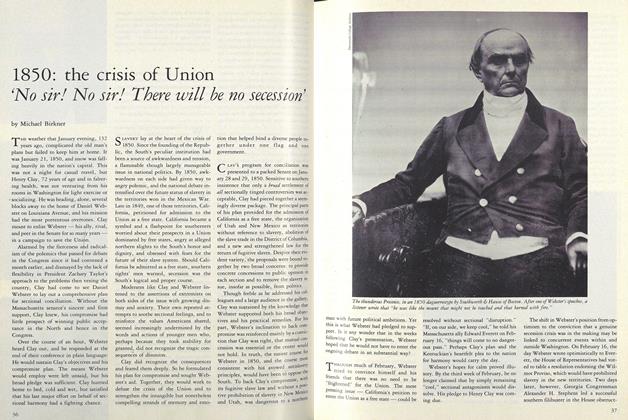

Feature1850: the crisis of Union 'No sir! No sir! There will be no secession'

March 1982 By Michael Birkner -

Feature

FeatureThe naivete of nuclear rivalry

March 1982 By George Kennan -

Feature

Feature'One day it came to me: sherry for breakfast was a good idea.'

March 1982 By Shelby Grantham -

Cover Story

Cover StoryPicking books Classic title, quirky tastes

March 1982 By Mary Ellen Donovan -

Article

ArticleSomeone wrote them, but did anyone read them?

March 1982 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1954

March 1982 By John L. Gillespie

Nancy Wasserman '77

-

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLetters to the Editor

APRIL 1978 -

Article

ArticleWearers of the Green

OCTOBER 1981 By Nancy Wasserman '77 -

Feature

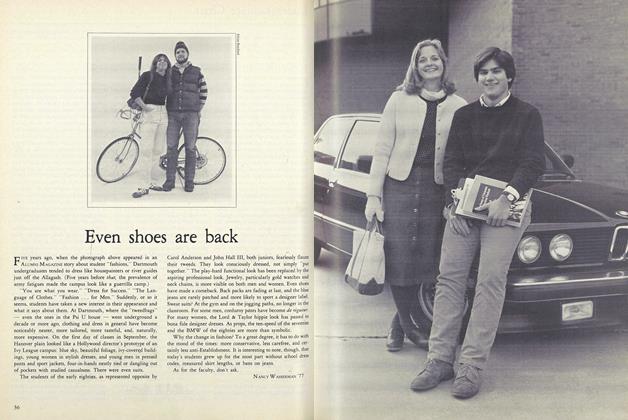

FeatureEven Shoes Are Back

DECEMBER 1981 By Nancy Wasserman '77 -

Article

ArticleTimothy Sheyda '72: Providing Food for Thought

JANUARY/FEBRUARY 1984 By Nancy Wasserman '77 -

Feature

FeatureGet a Job

NOVEMBER 1984 By Nancy Wasserman '77 -

Feature

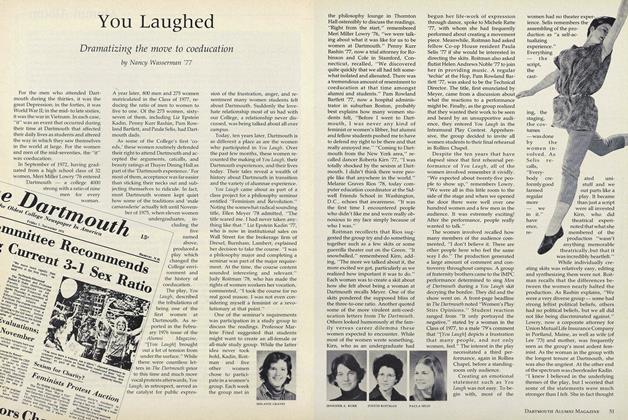

FeatureYou Laughed

JUNE • 1986 By Nancy Wasserman '77

Article

-

Article

Article49 MAKE 1923 GLEE CLUB

November, 1922 -

Article

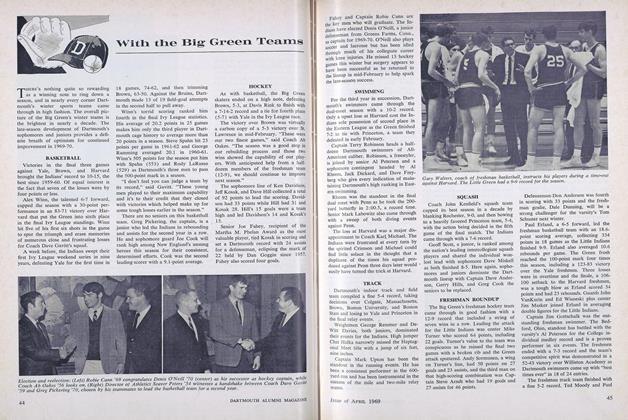

ArticleBig Green Teams

JUNE 1972 -

Article

ArticleGreen Jottings

November 1959 By CLIFF JORDAN '45 -

Article

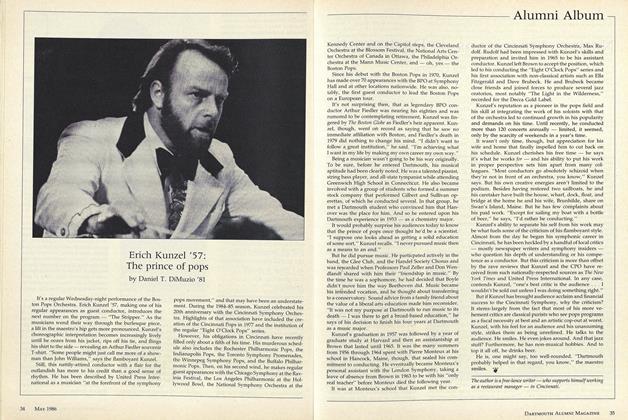

ArticleErich Kunzel '57: The prince of pops

MAY 1986 By Daniel T. DiMuzio '81 -

Article

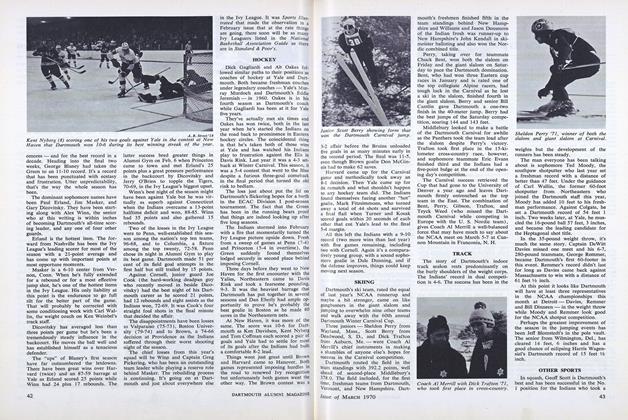

ArticleHOCKEY

APRIL 1969 By JACK DE GANGE -

Article

ArticleHOCKEY

MARCH 1970 By JACK DEGANGE