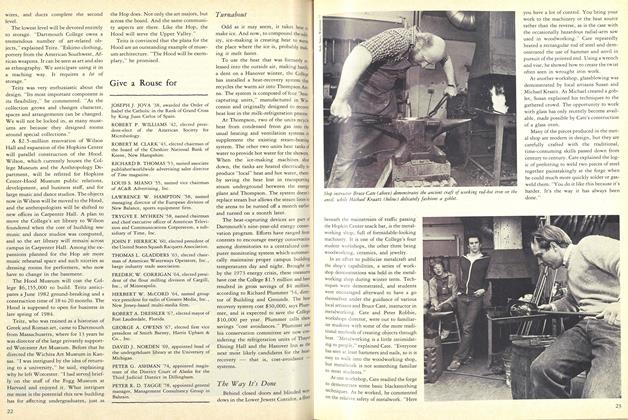

Odd as it may seem, it takes heat to make ice. And now, to compound the oddity, ice-making is creating heat to warm, the place where the ice is, probably making it melt faster.

To use the heat that was formerly released into the outside air, making hardly a dent on a Hanover winter, the College has installed a heat-recovery system that recycles the warm air into Thompson Arena. The system is composed of four "heatcapturing units," manufactured in Wisconsin and originally designed to recover heat lost in the milk-refrigeration process.

At Thompson, two of the units recycle heat from condensed freon gas into the usual heating and ventilation systems to supplement the existing steam-heating system. The other two units heat tanks of water to provide hot water for the showers. When the ice-making machines shut down, the tanks are heated electrically to produce "local" heat and hot water, thereby saving the heat lost in transporting steam underground between the energy plant and Thompson. The system doesn't replace steam but allows the steam lines to the arena to be turned off a month earlier and turned on a month later.

The heat-capturing devices are part of Dartmouth's nine-year-old energy conservation program. Efforts have ranged from contests to encourage energy conservation among dormitories to a centralized computer monitoring system which automatically maintains proper campus building temperatures day and night. Brought on by the 1973 energy crisis, these measures have cost the College $1.5 million and have resulted in gross savings of $4 million, according to Richard Plummer '54, director of Building and Grounds. The heat recovery system cost $30,000, says Plummer, and is expected to save the College $10,000 per year. Plummer calls these savings "cost avoidances." Plummer anc his conservation committee are now considering the refrigeration units of Thayer Dining Hall and the Hanover Inn as the next most likely candidates for the heatrecovery - that is, cost-avoidance systems.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureHotsy Totsy

April 1982 By Lomax Littlejohn -

Feature

FeatureThe Man Behind the Green

April 1982 By Rob Eshman -

Feature

FeatureEnd of a Golden era

April 1982 By Shelby Grantham -

Cover Story

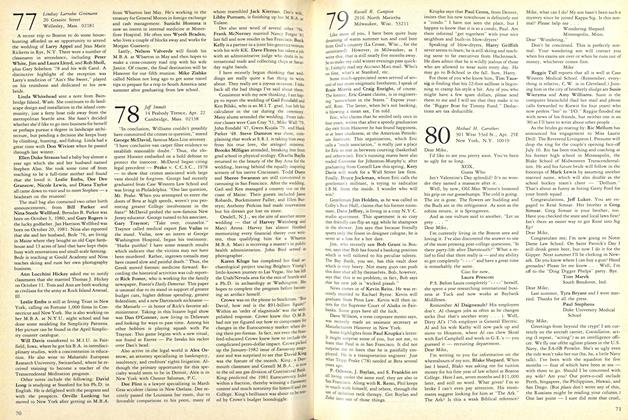

Cover StoryOn Mount Washington, where the Geum Peckii blooms and blows

April 1982 By Peter Heller -

Article

ArticleCONSTITUTION OF THE COUNCIL OF THE ALUMNI OF DARTMOUTH COLLEGE

April 1982 -

Article

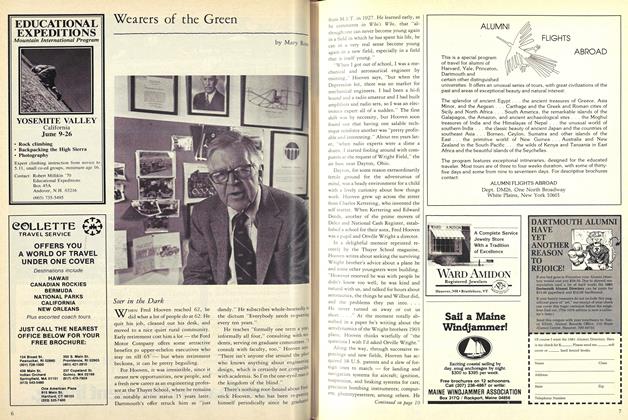

ArticleSeer in the Dark

April 1982 By Mary Ross

Article

-

Article

ArticleA WAH HOO WAH!

February 1946 -

Article

ArticleMasthead

January 1947 -

Article

ArticleAlumni Articles

December 1959 -

Article

ArticleTHE COLLEGE

November 1949 By C.E.W. -

Article

ArticleREPORT FROM THE COUNCIL

FEBRUARY 1989 By Patsy Fisher-Harris '81 -

Article

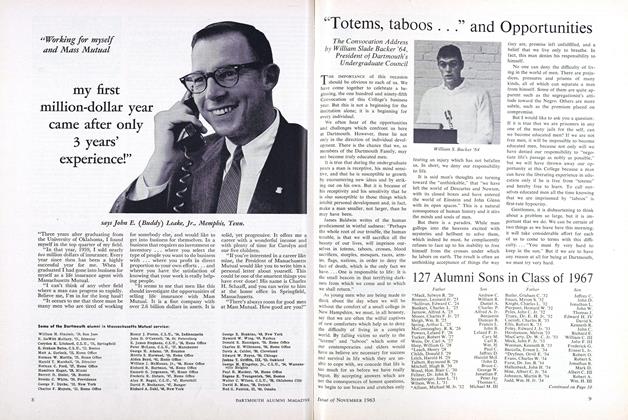

ArticleTotems, taboos . . and Opportunities

NOVEMBER 1963 By William Slade Backer '64