Late in the visionary sixties, there was a massive infusion of federal money into the nation's system of higher education. It was budget-relieving, and for the first time many colleges and universities were able easily to meet the demonstrated financial need of every student they admitted. The first year it happened at Dartmouth was 1967. The last was 1981.

Harland Hoisington '48, Dartmouth's director of financial aid, feels that the writing has been on the wall during the last few years of what administrators have come to call the Golden Decade. Financial-aid packages have contained ever-increasing percentages of self-help (jobs and loans) and correspondingly decreasing amounts of actual scholarship. Defining self-help as "the amount a student has to come up with before scholarship money is granted," Hoisington pointed out that the standard self-help amount at Dartmouth in 1979 was $2,100; in 1980, it was $2,400; in 1981, it was $2,750. "Inflation was marching on," said Hoisington. "That was difficult but manageable as long as federal funds were available. But they peaked in 1979-80. Next year they are going way down, and the big whammy will come in 1983—84."

Some cuts in federal loans and grants to higher education are already in effect; some are as yet only proposed; all are massive. Dartmouth's 1982-83 budget was set up in February, and it showed a shortfall of $1.5 million, dashing the College's hopes of eking out one more year of meeting the financial need of every student admitted. President McLaughlin has announced a return to the practice known as "admit/ deny," in which some needy students admitted on the basis of merit may have to be denied fiancial aid because, to put it simply, there isn't enough to go around.

Frantic recalculations are going on on campuses across the nation, but beyond them lie two deeper questions. First, how is the sudden drying-up of federal funds for scholarship going to affect the hard-won racial and economic diversity of many student bodies, and, second, how are students and parents and "the private sector" going to respond to having the bill for higher education returned thus ungently to their own laps?

Two-thirds of Dartmouth's own scholarship money is unendowed and comes from unrestricted income. (Two years ago, the unendowed portion was only 50 per cent, but unrestricted income cannot keep pace with current inflation.) At 34 per cent, Dartmouth's scholarship endowment is the lowest in the Ivy League. Princeton's, at 90 per cent, is the highest, but even there erosion is evident. Two years ago at Princeton it was 100 per cent; next year it is expected to fall to 85 per cent. "What really creams you," said Hoisington, "is cost increases. Last year's inclusive costs at Dartmouth (everything but travel) were $11,025. Next year they are expected to climb to $12,525. That means that the average scholarship will have to go up about $1,000." He shrugged helplessly. "If someday, something, whatever, slows down inflation, the problem would solve itself."

Last year's scholarship budget at the College was $5,150,000. For next year, $6,777,600 has been budgeted. Professor of Russian Richard Sheldon, who chairs the College's faculty committee on admissions and financial aid, pointed on the compelling facts that while during the seventies the scholarship budget increased at a steady $200,000 a year, in 1980-81 it went up by $700,000, and since then it has jumped by more than a million each year. "At that rate, the cost of continuing to meet the financial needs of everyone admitted would reach $13 million by 1985-86," he said. "That's the gist of the problem."

It is pretty clear, according to Sheldon, that no college in the country is going to be able to continue for long to finance every needy student qualified for admission. Some - Harvard, Yale, and Princeton among them — are trying to hang for one more year, but others have already thrown in the towel. Some, such as wesleyan and Brown, have decided on a den) deny policy of not admitting students the} cannot finance. When their scholarship funds are exhausted, they will stop admit ting solely on the basis of merit and start admitting on the basis of merit coupled with ability to pay. Behind the deny/deny solution are a somewhat technical adherence to the principle of continuing support for all of one's needy students and a sense of the cruelty of dangling carrots. Alfred Quirk '49, director of admissions at Dartmouth, pointed out that deny/deny is also administratively easier: "It is a much less bureaucratic and much more efficient way to deal with the scholarship shortfall than admit/deny. From a procedural point of view, admit/deny means much more work for us all in admissions and financial aid. It also increases the burden on a student's family, who must make the decision to accept or not. They may have to ask Uncle Fred for help, or go into debt more deeply than they would like to."

Nonetheless, Dartmouth's administration has taken the position that it should not deny to anyone qualified for admission a chance to come up with the money. According to Hoisington, this decision to return to admit/deny is based on history. "The data from three or four classes of the early sixties show that between a quarter and a third of those who were admit/denied did, in fact, matriculate," he explained.

The biggest worry on campuses across the nation is what Hoisington calls "the crucial issue" of economic and racial diversity. Dartmouth plans to take the exemption route around the threat of elitism and homogeneity posed by the scholarship shortfall. "Admit/deny bids will not go to minority students," said Sheldon, who explained that at Dartmouth minority applies specifically to three groups: black, Native American, and disadvantaged north-country students. "Otherwise, we would lose the minority representation we have worked so hard to get. Thirty-five per cent of the students at Dartmouth now receive financial aid in one form or another. We're keeping an eye on that, talking about a floor of some sort. We would be very concerned if that percentage dropped below 30."

As Quirk explained it, "The president has suggested giving preference in financial aid to minorities with high need. If someone needs only $3,000 or $4,000, he or she may be a candidate for admit/deny. But for those who need $10,000, or the whole $12,000, admit/deny is nonsense. In reality, for them it would be deny/deny. It would be an exercise in futility for the College to mount the kind of recruitment programs it has developed for minorities and then turn around and deny/deny them." Hoisington said flatly, "The College intends to maintain fully its interest in matriculating those groups to which it has made a commitment Native Americans, blacks, and north-country disadvantaged."

THE applications have always been ranked as a lot by merit scholastic and personal. But these days the process is complex, and financial-aid packages get doled out in spates along the way. For each class of 1,050 students, Dartmouth receives some 8,000 applications. The College's acceptance rate is roughly 60 per cent, so admissions makes bids to about 1,800 in order to secure an incoming class of 1,050.

Each application is read and judged by at least three admissions officers. Some 5,000 out of the 8,000, vetoed independently by all the readers, are automatically out of the running. Early-decision applications that guarantee acceptance of a Dartmouth bid constitute a separate group, from which some 350 bids, with financial aid where necessary, are made first. About 500 more bids and financial-aid offers are made on the basis of approval by all three first readers, and some 260 acceptances result. The last 450 slots in the class are filled by a process known as round table, in which the remaining applications (those that received neither all yeas nor all nays, but some mixture) are considered one by one by a larger committee of faculty and administrators. The committee convenes over a period of more than a month, beginning in March, to listen to and evaluate presentations ranging in length from 20 minutes to an hour each. Round-table results in a final bid list of about 1,000. "The admit/deny bids will be made here," said Sheldon, who explained (though without much conviction) that should this final 1,000 happen to contain only a few needy students, there might be enough scholarship money to avoid admit/deny altogether. "But," he said more realistically, "we anticipate that 70 to 90 of the class of '86 bids will have to be admit/ deny."

The president's minority preference comes into play as follows: black, Native American, or disadvantaged north-country applicants in the roundtable final list who demonstrate high need will be offered financial-aid packages first. Remaining resources will be allocated according to need from the top down among the meritranked remainder. When they run out, they run out.

Quirk's view is that admit/deny will affect a relatively small percentage of the class, and he downplayed the possible effect on diversity: "I'm guessing at this point that changing the financial situation for anywhere from 50 to 100 families might not affect diversity. Our small size is in our favor. It's likely that the institutions the cuts will hit hardest will be those with the most diversity the big state universities, for instance, where for many students $400 will be hard to scrape up." Diversity, said Quirk, is a very hard thing to pin down, and he stressed the complexities of determining financial need: "We tend to think of the needy as the lower middle class, the poor, and the very poor. That's not necessarily true. Our need analysis takes into account two families side by side in suburbia - one in great shape financially and the other in deep financial trouble because of debt, or illness, or whatever."

Of more concern to Quirk are the responses he anticipates from admit/deny students and their parents. His experience of admit/deny admissions in the sixties leads him to expect a lot of upset. "People will feel that an admit/deny bid is a rejection letter," he said. "It's a very difficult thing to receive. For many 17- and 18year-olds it will be the first time they have ever been rejected for anything, the first time someone has said no. Competitive selection admissions is a difficult experience, and admit/deny just adds to the difficulty, particularly for the student who has his or her heart set on Dartmouth and may well have attractive offers from elsewhere. Candidates usually have impressive credentials, and it seems capricious to students that one Ivy League school admits them while the others don't, or that several admit them but only one offers financial aid. In the golden era, it was almost literally possible for a candidate accepted by several schools to make the decision about which place to choose without considering money at all. Reductions in financial aid are, of course, reducing that option of choice."

As grant moneys lag and work-study loads peak, loans will come to play an increasing part in the lives of many students and their families. "The College needs another loan program," said Hoisington, and he described the proposed Dartmouth Educational Loan Company, to be financed by the sale of tax-exempt bonds, beginning perhaps as early as May of this year. Dartmouth has already been authorized by the state of New Hampshire to offer investors tax-exempt bonds at 10 or 11 per cent to create a fund from which students may borrow at 12 or 13 per cent, the difference going toward the administration of the company and the covering of defaults on repayment. President McLaughlin is also concerned, according to Quirk, about the scarcity of educational loans available to parents. "The thrust in the past decade has been toward loans for students," said Quirk. "There needs to be a parent option to borrow money for a child's education. Williams does that, I think, and Dartmouth already has some such money available, but I don't know how much."

Such locally financed loans will be far less attractive than the very low-interest Guaranteed Student Loans of the golden decade but they will be better than nothing. For the rest, the financial-aid people at Dartmouth plan to keep a weather eye out for miracles.

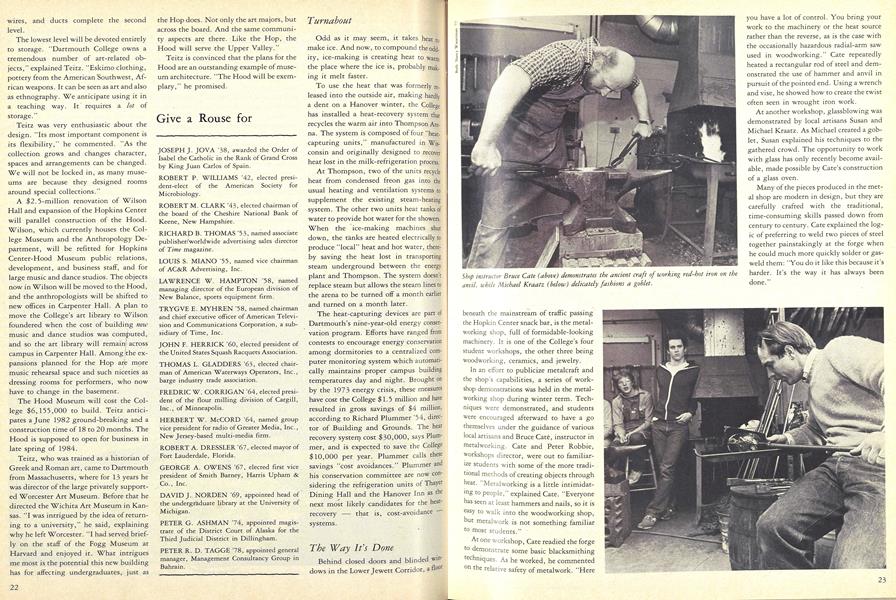

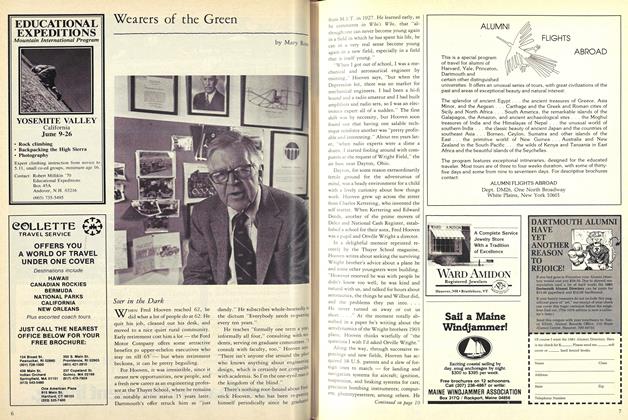

Harland Hoisington, director of financial aid(above), and Alfred Quirk, director of admissions mouth will no longer meet the demonstrated financial need of everyone admitted, it will keepthe practice of "need-blind" admissions.

Richard Sheldon, chair of the faculty's committee on admissions and financial aid, explained thatthe College is still "groping its way through" the problems created by recent cuts in federal aid.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureHotsy Totsy

April 1982 By Lomax Littlejohn -

Feature

FeatureThe Man Behind the Green

April 1982 By Rob Eshman -

Cover Story

Cover StoryOn Mount Washington, where the Geum Peckii blooms and blows

April 1982 By Peter Heller -

Article

ArticleCONSTITUTION OF THE COUNCIL OF THE ALUMNI OF DARTMOUTH COLLEGE

April 1982 -

Article

ArticleSeer in the Dark

April 1982 By Mary Ross -

Class Notes

Class Notes1965

April 1982 By Robert D. Blake

Shelby Grantham

-

Feature

FeatureMen and Women: What's the Difference?

OCT. 1977 By Dan Nelson, Shelby Grantham -

Feature

FeatureJohnny can't write? Who cares?

January 1977 By Shelby Grantham -

Feature

FeatureThe big eye in Arizona

SEPTEMBER 1981 By Shelby Grantham -

Cover Story

Cover StoryThe conquest of Kiewit (sort of)

JAN.- FEB. 1982 By Shelby Grantham -

Article

ArticleThe Children's Own Curator

MAY 1983 By Shelby Grantham -

Feature

FeatureHigh Tech Crisis

JUNE 1983 By Shelby Grantham

Features

-

Feature

FeatureMcCulloch Heads Council

JULY 1971 -

Feature

FeatureFather Bill's Answers

APRIL 1988 By Benjamin Hart ’81 -

Feature

FeatureTHE CREATIVE ARTS

May 1954 By IRWIN ED MAN -

Feature

FeatureTHE FORFEIT

OCTOBER 1990 By Ken Johnson '83 -

Feature

FeatureThe Next Bus Home

September 1993 By Regina Barreca '79 -

Cover Story

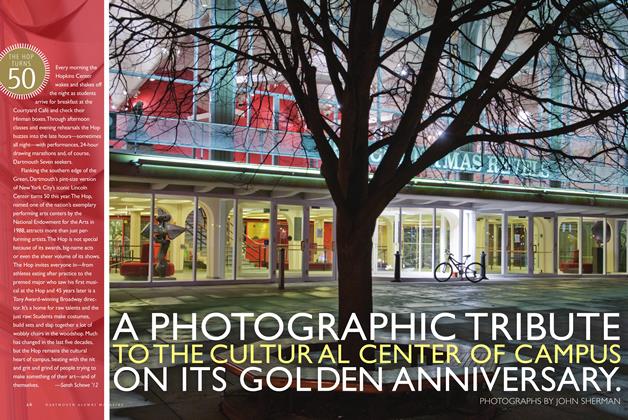

Cover StoryEncore!

May/June 2012 By Sarah Schewe ’12