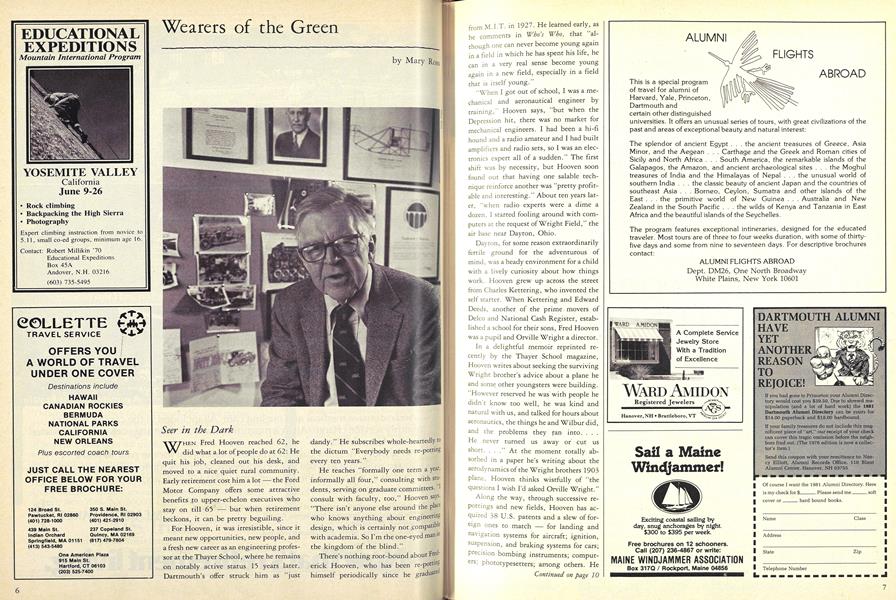

When Fred Hooven reached 62, he did what a lot of people do at 62: He quit his job, cleaned out his desk, and moved to a nice quiet rural community. Early retirement cost him a lot the Ford Motor Company offers some attractive benefits to upper-echelon executives who stay on till 65 but when retirement beckons, it can be pretty beguiling.

For Hooven, it was irresistible, since it meant new opportunities, new people, and a fresh new career as an engineering professor at the Thayer School, where he remains on notably active status 15 years later. Dartmouth's offer struck him as "just dandy." He subscribes whole-heartedly to the dictum "Everybody needs re-potting every ten years."

He teaches "formally one term a yearinformally all four," consulting with students, serving on graduate committees. consult with faculty, too," Hooven sap "There isn't anyone else around the pace who knows anything about engineening design, which is certainly not compatible with academia. So I'm the one-eyed man in the kingdom of the blind."

There's nothing root-bound about Frederick Hooven, who has been re-potting" himself periodically since he graduate from M.I T. in 1927. He learned early, as he comments in Who's Who, that "although one can never become young again in a field in which he has spent his life, he can in a very real sense become young again in a new field, especially in a field that is itself young."

"When I got out of school, I was a mechanical and aeronautical engineer by training," Hooven says, "but when the Depression hit, there was no market for mechanical engineers. I had been a hi-fi hound and a radio amateur and I had built amplifiers and radio sets, so I was an electronics expert all of a sudden." The first shift was by necessity, but Hooven soon found out that having one salable technique reinforce another was "pretty profitable and interesting." About ten years later, "when radio experts were a dime a dozen, I started fooling around with computers at the request of Wright Field," the air base near Dayton, Ohio.

Dayton, for some reason extraordinarily fertile ground for the adventurous of mind, was a heady environment for a child with a lively curiosity about how things work. Hooven grew up across the street from Charles Kettering, who invented the self starter. When Kettering and Edward Deeds, another of the prime movers of Delco and National Gash Register, established a school for their sons, Fred Hooven was a pupil and Orville Wright a director.

In a delightful memoir reprinted recently by the Thayer School magazine, Hooven writes about seeking the surviving Wright brother's advice about a plane he and some other youngsters were building. However reserved he was with people he didn't know too well, he was kind and natural with us, and talked for hours about aeronautics, the things he and Wilbur did, and the problems they ran into. . . . He never turned us away or cut us short. . . At the moment totally absorbed in a paper he's writing about the aerodynamics of the Wright brothers 1903 plane, Hooven thinks wistfully of "the questions I wish I'd asked Orvilie Wright."

Along the way, through successive repottings and new fields, Hooven has acquired 38 U.S. patents and a slew of foreign ones to match for landing and navigation systems for aircraft; ignition, suspension, and braking systems for cars; precision bombing instruments; computes. phototypesetters; among others. He has worked for General Motors, Dayton Rubber, Bendix, and himself. He worked closely with the Army Air Corps, as an independent contractor, during much of World War 11. More than 20 years ago, during the decade he was an executive engineer and later a management consultant for Ford, he designed front-wheel drive systems that, ironically, were put in production for General Motors cars but not for Ford's. He collaborated on the first successful heart-lung machine and, as a volunteer developed a line of psychophysiological measuring devices.

But, of all his inventions, Hooven is proudest of the radio direction finder for aircraft navigation he developed in the mid-thirties. "It was my own idea, and it completely dominated the scene for that kind of device for a time roughly corresponding to the life of the DC-3. It made it routine to cross the ocean, where it had been an adventure before."

Five prototypes of the Hooven direction finder were built. One was used for the first automatic blind landings ever made; one was installed on the first DC-3 in passenger service, another on a 1936 transatlantic flight. One was installed, then removed from Amelia Earhart's plane before she took off across the Pacific on the 1937 flight from which she never returned. Hooven speculates that "she may have been prodded by the Navy or the fellow who built the other one I suspect she was to take mine out and put his in." The substitute was a relatively primitive device lacking a right-left directional indicator, so the pilot couldn't tell from which of two' opposite directions a signal originated. Hooven's invention, on the other hand, had far greater range and guided a plane directly toward a broadcast station. It has been widely presumed that Earhart would not have missed her guiding station, hence not been lost, had the Hooven device not been removed from her plane. He recalls, back in 1935, flying from Dayton to Dallas and back entirely on automatic controls, with the direction finder hooked up to the auto-pilot, controlled by a series of devices that tuned in the radio stations, marked positions, governed the rate of descent, and shut off the throttle. It was a simple system, he claims, set up but never put into use for no apparent reason. "But people don't behave logically," he comments.

The immunity of people and organizations to logic, "the only weapon I have," is one of a number of issues that Hooven gets "heated up" about. Another is the corporate theory of management for its own sake - he calls it "the Harvard Business School fallacy" that holds the product to be irrelevant to the management of a company. "It was the philosophy at Ford when I was there," he Says, "and it's one of the prevailing difficulties with American business right now. One of the things you have to take into account in business administration is the realities of technology and ways of getting along with technological people. ... If you're going ,to manage a company, you've got to be responsible for the product."

Hooven's faith in technology and the inventive spirit is epitomized by his conviction that the day is not far off when energy will be a trivial matter because it will be so easily obtained. With good management and a modicum of wisdom - "and we've shown no signs of wisdom so far" he believes that available natural gas will tide us over the time when there's not enough oil.

"One thing I foresaw a long time ago that I will stick by is that one day we'll find a way to get electricity to drive automobiles and to supply our houses, and we'll no longer be dependent on power companies, wires, heat engines, and the rest." He visualizes "and this is strictly a Dick Tracy kind of prediction, not an engineering kind," he cautions "a little box about this big," Hooven . measures some 18 inches of air between his hands, "into which you'll occasionally put a little water and this converts the mass of the hydrogen into helium and releases energy as nuclear energy, electrical energy. The day will come when we figure out how to produce nuclear energy without burning the barn down, .to get it without all this radiation."

"Oh, the scientists bristle at this, he declares with a broad grin, "but they're the world's worst predicters of the future. They predict incredible accomplishments for the engineers, but they never, never mention the possibility of a radical breakthrough in science - which there is regularly. The rules of physics change regular!} every 100 years. Einstein changed them beyond all recognition beginning in 1905, the year I was born. He shook up the whole world, and somebody's going to do that again pretty soon."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureHotsy Totsy

April 1982 By Lomax Littlejohn -

Feature

FeatureThe Man Behind the Green

April 1982 By Rob Eshman -

Feature

FeatureEnd of a Golden era

April 1982 By Shelby Grantham -

Cover Story

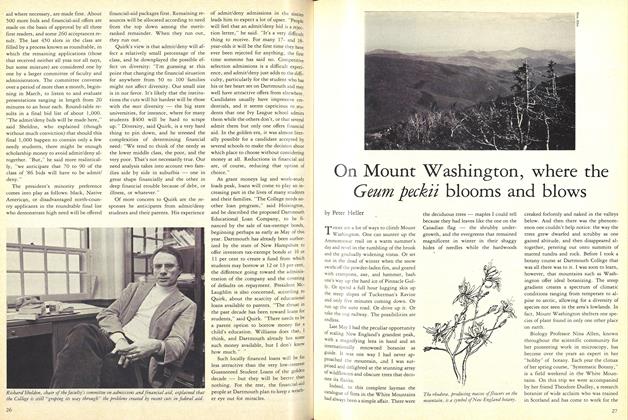

Cover StoryOn Mount Washington, where the Geum Peckii blooms and blows

April 1982 By Peter Heller -

Article

ArticleCONSTITUTION OF THE COUNCIL OF THE ALUMNI OF DARTMOUTH COLLEGE

April 1982 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1965

April 1982 By Robert D. Blake

Mary Ross

-

Feature

FeatureOMBUDSMAN

OCTOBER 1971 By MARY ROSS -

Article

ArticleTriple-Threat Academician

DECEMBER 1971 By MARY ROSS -

Feature

FeatureBaseball Chief

APRIL 1972 By MARY ROSS -

Article

Article300 Million Years Ago . . .

NOVEMBER 1981 By Mary Ross -

Article

ArticleSharing Faith and Fear

MAY 1982 By Mary Ross -

Article

ArticleLost and Found: Sino-American Reunion

JUNE 1982 By Mary Ross