There are a lot of ways to climb Mount Washington. One can saunter up the Ammonoosuc trail on a warm summer's day and revel in the tumbling of the brook and the gradually widening vistas. Or set out in the dead of winter when the snow swirls off the powder-laden firs, and geared with crampons, axe, and hammer, bash one's way up the hard ice of Pinnacle Gully Or spend a full hour lugging skis up the steep slopes of Tuckerman's Ravine and only five minutes coming down. Or run up the auto road. Or drive up it. Or take the cog railway. The possibilities are endless.

Last May I had the peculiar opportunity of scaling New England's grandest peak, whth a magnifying lens in hand and an internationally renowned botanist as guide. It was one way I had never approached the mountain, and I was surprised and delighted at the stunning array of wildflowers and obscure trees that decorate its flanks.

Indeed, to this complete layman the catalogue of flora in the White Mountains ad always been a simple affair. There were the deciduous trees maples I could tell because they had leaves like the one on the Canadian flag - the shrubby undergrowth, and the evergreens that remained magnificent in winter in their shaggy hides of needles while the hardwoods creaked forlornly and naked in the valleys below. And then there was the phenomenon one couldn't help notice: the way the trees grew dwarfed and scrubby as one gained altitude, and then disappeared altogether, petering out onto summits of matted tundra and rock. Before I took a botany course at Dartmouth College that was all there was to it. I was soon to learn, however, that mountains such as Washington offer ideal botanizing. The steep gradient creates a spectrum of climatic conditions ranging from temperate to alpine to arctic, allowing for a diversity of species not seen in the area's lowlands. In fact, Mount Washington shelters one species of plant found in only one other place on earth.

Biology Professor Nina Allen, known throughout the scientific community for her pioneering work in microscopy, has become over the years an expert in her "hobby" of botany. Each year the climax of her spring course, "Systematic Botany,"

is a field weekend in the White Mountains. On this trip we were accompanied by her friend Theodore Dudley, a research botanist of wide acclaim who was trained in Scotland and has come to work for the National Arboretum in Washington.

Late May is a splendid, gentle time in the mountains of New Hampshire. The land seems to rejoice in its new habit of tender leaves, shade upon shade of subtle greens and burnt reds climbing the slopes and filling the valleys, as beautiful and various to my mind as autumn foliage. The air on clear days is soft with warmth, lacking the aggressive heat of the summer months.

HOISTING day packs stuffed with sweaters, rain gear, cameras, lunches, and field guides, we set out from Pinkham Notch Lodge on just such a morning. There were ten of us, and we radiated an esprit de corps not unworthy of a gang of gold prospectors. I, for one, was eager to spot Geumpeckii, a plant resembling a large strawberry which, inexplicably, is known to occur only on Mount Washington and on tiny Brier Island, Nova Scotia.

We hadn't even cleared the parking lot when Dudley called out in his precise accent, "Who can tell me the name of this herb?"

We stopped. The plant, about a foot high, had small many-petaled flowers, pale lavender with yellow centers. Off came our carefully arranged knapsacks; eight pairs of hands dug for Newcomb'sWild/lower Guide, an excellent, easily useful field manual for eastern flowers.

"It's in the Asteraceae family," suggested a small blonde who had cleaned me out in a poker game the night before. The Asteraceae include daisies, asters, and sunflowers. From the appearance of our subject, it seemed a good guess.

"Mm-hmm," said Dudley, as the pages of the pocket guides were riffled in a race to find the species.

"Keying" is a surprisingly rewarding process of identifying a particular plant. In fact, once one surmounts the initial puzzle of a few technical words, it gets to be downright fun. A key is a numbered list of plant characteristics, progressing from the more general to the more specific, usually given in pairs. You choose the one which better applies to the flower or tree before you. The one you pick then directs you to another pair of characteristics, and so on, until you have narrowed your specimen down to a few closely related species. A final set of characteristics usually brings a positive identification and a shout of triumph.

"Daisy Fleabane!" hooted a myopic cross-country runner.

"How large are the flower heads?" asked Dudley.

"Oh . . . oh, yeah. Common Fleabane! Erigeron philadelphicus."

"Exactly," said Dudley with a chuckle.

A New Englander by origin, he was wearing a tweed jacket with a sprig of leaves in the lapel. Despite this dapper display, Dudley looked more like a sea captain than a noted botanist. Above a trim black beard and deeply tanned cheeks, his eyes were encircled by fine squint wrinkles. He spends half of each year in some of the wildest country in the world, from Tierra del Fuego to Afghanistan to China, collecting and classifying plants. On such trips he is accustomed to carrying a Winchester under-over, the .22 for shooting specimens down from tall jungle trees ("If you're a good shot," he said, "you can nick one side of a branch, then the other, then hit it dead in the center and down it falls") and the shotgun to bag exotic birds for dinner. Our jaunt was tame stuff, but he seemed to relish the exploration of this north-country flora as much as we did.

We took up the packs again and walked past the trailhead into the dappled shade of the woods. It was like stepping into several fathoms of Caribbean water. The light sifting down through a million green lenses shifted and darted like a school of fish. Here and there along the trail a colorful wildflower peaked out from the undergrowth.

It is strange that in all my hikes and runs along trails such as this, I had never bothered to identify or even much notice the bountiful wildflowers that grow along the way, so lovely that their cultivated cousins look gaudy and pretentious by comparison. For the most part they are small, often tiny, and to see them at all one has to be looking. We were looking now, intent on naming anything that poked its head out of the rocky soil.

"Ted, do your stuff," said Nina Alien, pointing with her staff to a large shrub flagged with clustered white flowers.

That's a viburnum," said Dudley from down the slope. He approached the plant. "Look at the broad leaves and the tiny white flowers surrounded by larger ones. That's Viburnum lantanoides. What do you call it here? Oh, yes, hobblebush, I think."

Professional botanists have a terrible time with common names. Usually applied arbitrarily, they vary from region to region and lead to confusion over the relationships between species of plants. Thus, sagebrush is not even closely related to garden sage, and what they call cedar in Colorado is far different from the California cedar. A plant's Latin name, however, is universal.

On up the steepening trail we climbed. It is amazing for a New Englander who has never seen the trees for the forest to discover the wealth and diversity of plants in his own backyard. With nothing more advanced than a Peterson Field Guide to Treesand Shrubs, we identified alders, hazelnuts, beeches, hickories, shads, elders, ash, and a variety of maples, cherries, birches, pines, firs, and spruce. The flowers were less obvious and more remarkable. With the help of Newcomb's guide we discovered bluebeads, starflowers, trout lilies, jack-in-the-pulpits and goldthreads, irises, bunchberries, bellworts, honeysuckles, Lady's Slippers, bluets, and violets, to name a few. With every identification, sometimes with the book and gradually more and more without, there Came an extraordinary sense of reward. The Indian saying that to name is to have power to make sense.

" ISN'T this fine!" I exclaimed to a good- humored Dudley. "Do you enjoy climbing mountains?"

"I detest it," he answered with a wry smile. "I could never understand climbing mountains just for the sake of climbing mountains."

For someone who has spent months running up and down the Peruvian Andes in search of certain kinds of vegetation, that might seem incongruous. (I later learned that Dudley, who has slept half his nights in a tent, also dislikes camping. When his family travels and camps, he stays in a motel.) But in pursuit of his botanical research, any hardship mountains, typhoons, and jungles is cheerfully accepted.

We stopped to eat lunch in a smal clearing. Across the notch, mountains spotted like Holsteins with the shadows of clouds receded in ranks to the east. The talk as we munched cheese and nuts returned inevitably to botany. Someone remarked on the thinning of the leafy deciduous trees and the preponderance of spruce and fir. Birch and pin cherry seem to be the only hardwoods that can tolerate the higher altitude. Allen pointed out the dryness of the resin dots on the bark of a balsam fir which, she said, indicates a dry spring.

As the others talked, I wandered up the trail. After a few hundred yards I came out of the trees and onto the cushioned tundra of the Alpine Gardens. Suddenly the view was immense, the horizon spilling away on three sides. Ahead, the trail, marked now by rock cairns, meandered over the wide shelf, past piles of talus and through lowlying leather-leafed plants thickly covering the thin soil. Having left my guidebooks and mentors behind, I was unable to identify much of anything. At a clump of lichen I knelt to feel the rubbery leaves and saw a small white flower growing against a rock. It had five petals on a three-inch stem, and a three-lobed leaf.

It looks like a strawberry, I thought. But too big. Sure! Geum peckii! Unique to this mountain and to one distant island.

Damn! Geum peckii has yellow blossoms. What's this one then? Resisting my temptation to pluck the flower, I staked my claim with a bandana and a stone and ran back down the trail.

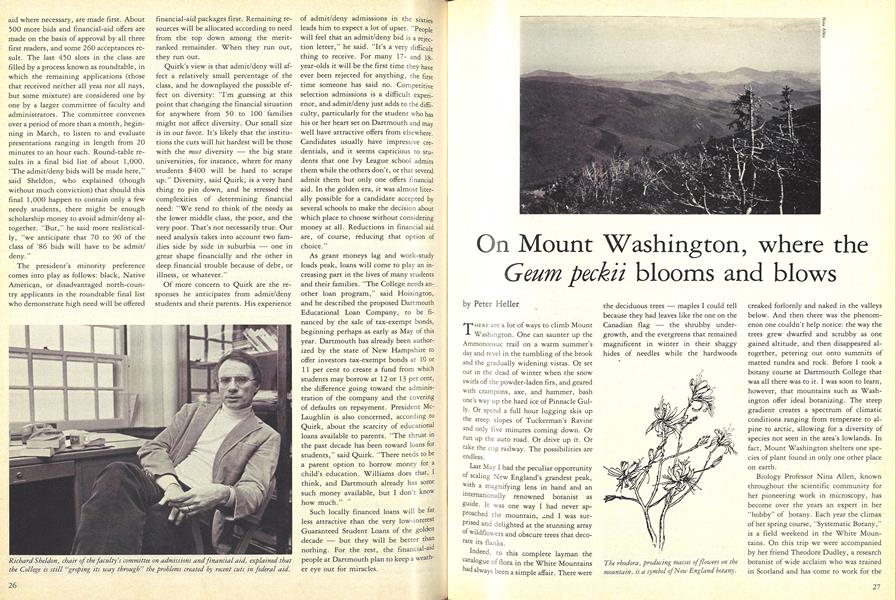

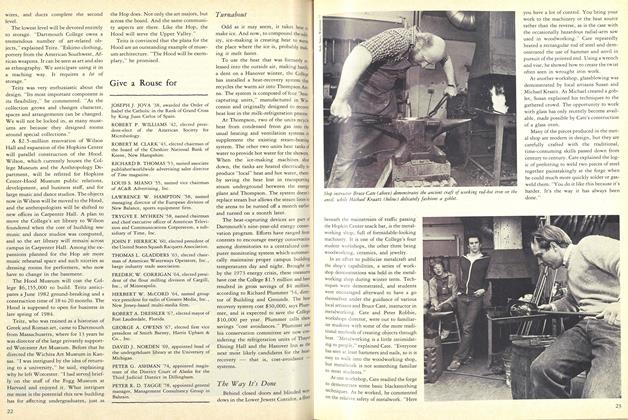

The rhodora, producing masses of flowers on themountain, is a symbol of New England botany.

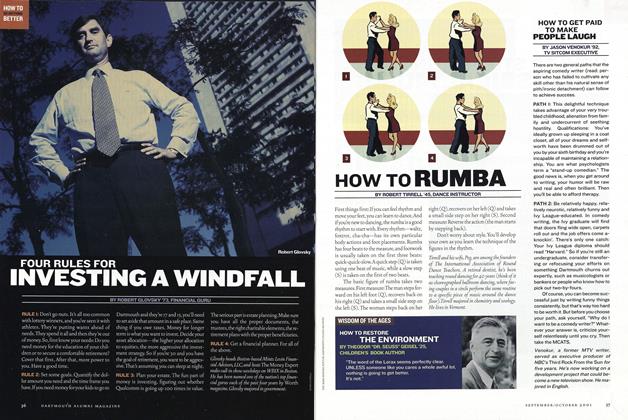

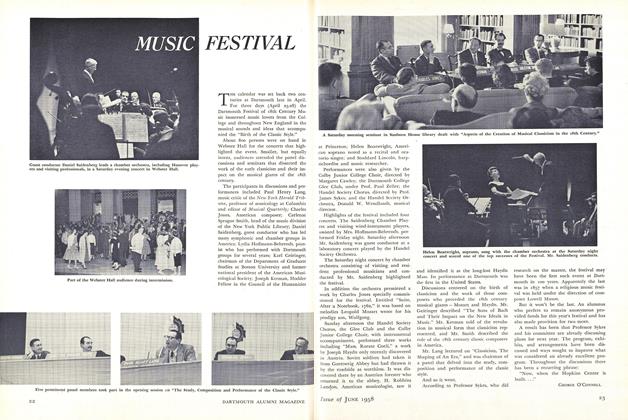

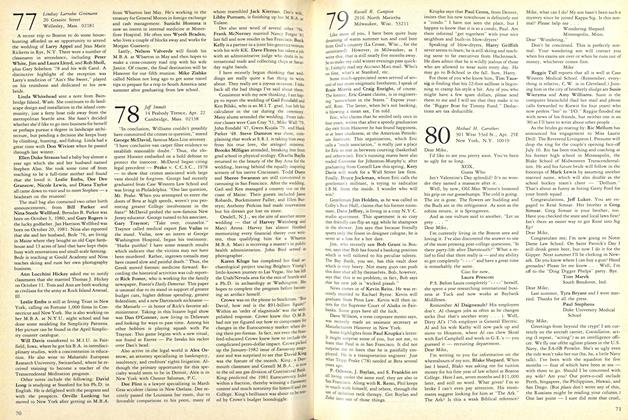

Striking some rather eccentric poses for closeinspection, a quartet of Dartmouth studentsstudies plant-life growing in the Alpine Gardens near the summit of Mount Washington.

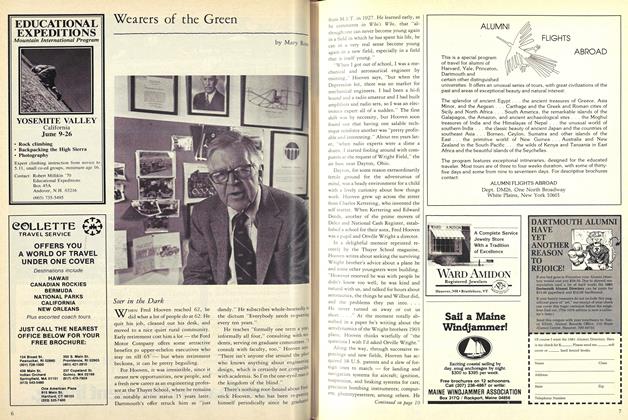

Keying-out a tree (above) under the guidance ofTheodore Dudley. The bluets (below), part ofthe same family as coffee plants, also heraldspring on New England's blusteriest peak.

Peter Heller 'B2 is founding editor of the Stonefence Review, a literary magazine atthe College, and a kayaker.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureHotsy Totsy

April 1982 By Lomax Littlejohn -

Feature

FeatureThe Man Behind the Green

April 1982 By Rob Eshman -

Feature

FeatureEnd of a Golden era

April 1982 By Shelby Grantham -

Article

ArticleCONSTITUTION OF THE COUNCIL OF THE ALUMNI OF DARTMOUTH COLLEGE

April 1982 -

Article

ArticleSeer in the Dark

April 1982 By Mary Ross -

Class Notes

Class Notes1965

April 1982 By Robert D. Blake