IF you were asked to name several contemporary American novelists whose books possess significant literary and social merit, which novelists would you choose? This is a question that I am asked rather frequently. Whenever I reveal to educated strangers that I am a Dartmouth professor who teaches American literature, the question eventually comes up. What is generally expected is a list of names, titles, and plot summaries delivered in the manner, say, of the New Yorkers brief reviews of movies. And I eventually get around to the titles and authors. However, using professorial license, I squeeze in between the names and titles mini-lectures on the dubious value and, in some cases, the plain idiocy of comparing and rating novelists and their novels. Creative writers, after all, are not athletes breaking world records. Moreover, novels achieve their authority and power and work their magic in mysterious ways. Herman Melville's MobyDick, for example, published in the middle of the nineteenth century, is now widely regarded as a great American classic. But the glorious resurrection of Moby Dick and Melville is a twentieth-century literary phenomenon. Some of his contemporaries dismissed him as second-rate. Others considered him crazy.

In short, there was no reliable way of predicting during the fifties that, say, Saul Bellow, our most recent Nobel laureate, would become the successful and highlyacclaimed novelist that he is today. But in 1959, Norman Mailer, America's literary king of controversy, tried. He offered the prophecies of the literary prospects of fellow writers who had started out after World War II. Labelling his assortment of quips and barbs "Quick and Expensive Comments on the Talent in the Room," he administered his own idiosyncratic literary acid test (never clearly defined) and recorded his conclusions. Bellow's style, Mailer felt, was "willed and unnatural." He added: "I cannot take him seriously as a major novelist. I do not think he knows anything about people, nor about himself . . . " Mailer dismissed Salinger (who was very popular at the time) as "the greatest mind ever to stay in prep school." He spoke highly of Truman Capote, calling him "the most perfect writer" of His generation, and asserted that Capote wrote "the best sentences, word for word, rhythm for rhythm."

Now, gentle reader, you may judge for yourself the prophetic accuracy and value of Mailer's comments. Furthermore, you may be wondering what Mailer saw as his own literary fate nearly twenty-five years ago. His literary ambitions and expectations, even then, were as olympian as they are now. In fact, the book in which his "quick and expensive" comments appeared is a symbol and foretaste (as the title Advertisements for Myself unabashedly asserts) of his talent and ambition. Advertisements is a brilliant hybrid of essays, fiction, and autobiography that identifies some of the problems faced by the writers who started out after the Second World War.

Mailer realized that certain technological advances along with the threat of atomic war had made the world his literary forebears knew vanish forever. He understood that the world was well on its way to becoming what it is today. Now, we dwell rather precariously in what Marshall McLuhan called a global village. Wired, controlled, and monitored by satellites and computers, the earth has become something reminiscent of a globe twirling upon a classroom table. Mailer states in Advertisements that even one's death may be robbed of its traditional significance: "... we might be doomed to die as a cipher in some vast statistical operation in which our teeth would be counted, and our hair would be saved, but our death itself would be unknown, unhonored and unremarked, ... a death by deus ex machina in a gas chamber or radioactive city."

DESPITE its spectacular power and its many-splendored forms, "miraculous technology" has not been the only significant force animating and attracting the American novelist's potential audience. During the sixties and seventies, American society and culture itself underwent a dramatic stage of metamorphosis. So some writers despaired. How could the writer's imagination compete with what was actually happening in America and the world? How could it compete with lunar landings, the Vietnam War; a series of political assassinations; race riots in the streets; long hair and nudity on the stage; heroin, mescaline, marijuana, and cocaine in American brains? Which American writer, for example, could have dreamed into existence the improbable circumstances and inimitable characters involved in the Watergate scandal? The situation had become so frustrating by the early sixties that Phillip Roth concluded: "The actuality is continually outdoing our talents, and the culture tosses up figures almost daily that are the envy of almost any novelist." So it was no longer a case of life imitating art. American life threatened to usurp the role of the storybook by casting an actual spell on the American population, creating characters and plots truly stranger than fiction.

Although the American novel did not die during the sixties as some writers and critics thought, traditional thinking about the form and content of American fiction was challenged. Several writers began to explore the territory that exists between fiction and fact, an exploration that led to the so-called "new journalism" and the "non-fiction novel." In short, some firstrate journalists began using the techniques that writers of fiction had used for a century and novelists took actual historical events and reworked them in their own imaginations. William Styron's The Confessions of Nat Turner (1967) and Norman Mailer's The Armies of the Night (1968) come to mind. Styron retold the story (it sparked a heated public controversy) of the leader of a famous slave rebellion. Mailer's The Armies of the Night, subtitled The Novelas History, proved to be a good example of new journalism. Reporting on an anti-war march on the Pentagon in 1967, Mailer put himself at center stage. Viewing himself as witness and moral prophet, a central American personality upon whom history had conspired to work itself out, he brilliantly used the techniques of the novelist, the journalist, and the autobiographer to explore the meaning of the event in the life of the nation.

This particular state of world affairs brought with it strikingly different and unprecedented situations and pressures for novelists trying to describe American life. Bellow has commented eloquently on a central problem facing writers as we approach the 21st century. He tells us that the world no longer turns to art poetry, paintings, and music to find the wonderful. Technology has now become an extraordinary source of enchantment. Modern wonders such as cable television, testtube babies, and space shuttles captivate us. Given such circumstances, he feels that literature cannot compete. According to Bellow, we live in a world in which the machine (or "miraculous technology" as he calls it) wars against the storybook. On the one hand, there is the machine "the product of innumerable brains and wills acting in unison. ' And on the other, there is the storybook artifact of the individual consciousness. The machine is the product of what Bellow labels the "fictive superself." "Acting in unison and according to plan, {it} produces jet planes, atom smashers, computers, rockets and other modern technlogical wonders." When the fictive superself needs information about the world, it turns to its experts produced by universities and licensed by governments. The storyteller, the novelist, in such a system of things is but a child, no longer trusted as a public sage, no longer dependable as an informant. Bellow notes that the contemporary nature of the world has driven some writers to literary extremes: "Writers trying to keep the attention of the public have turned to methods of shock, to obscenity, and supersensationalism, adding their clamor to the great noise now threatening the sanity of the civilized world."

Another group of more innovative writers labelled postmodernists established a new set of assumptions about writing fiction. When writers such as Donald Barthelme, John Barth, Thomas Pynchon, Robert Coover, William Gass, and Ishmaei Reed (to name a few) started publishing their stories and novels, readers were forced to discard their usual expectations. These writers rarely tried to represent reality as we ordinarily know it. The assumptions of realistic" fiction involving plot, character, setting, and narration are seldom applicable to their works. Their fiction is marked by a playful, self-conscious inventiveness. So they devoted a considerable amount of narrative energy to the peculiar twists and turns of the story being constructed. In "The Death of the Novel," for example, author Ronald Sukenick sums it up this way: "The contemporary writer ... is forced to start from scratch: Reality doesn't exist, time doesn't exist, personality doesn't exist. God was the omniscient author, but he died; now no one knows the plot. ..." Although there are a few general characteristics which most of the postmodernists may share, the writers form an extremely diverse group. And their novels and stories explore unique points of view.

Take, for example, Thomas Pynchon. His novel, Gravity's Rainbow, co-winner of the 1973 National Book Award for Fiction, is nearly 800 pages long and has as its subject the workings of German, Russian, British, and American intelligence groups. The book has neither plot nor characters in the traditional sense, although much of the action centers on the construction and the launching of a German rocket carrying an extremely powerful warhead. Along the way, the writer displays an extraordinary knowledge of theoretical physics, Wagnerian operas, comic books, and other esoterica. A mystery man himself who virtually no one knows or has even seen in a photograph, Pynchon has a significant following. And he has been highly praised for his extraordinary command of language, his stylistic mastery. However, if your knowledge of theoretical physics is not what it used to be, Gravity's Rainbow may be a demanding and exhausting undertaking.

Ishmael Reed (who has taught at Dartmouth) does something similar in several of his novels. But while his work may share some of the characteristics of Coover and, to the degree that it is satirical, Mark Twain, Reed is a true original. Even the titles of some of his novels The FreeLance Pall-Bearers, Yellow-Back Radio BrokeDown, Mumbo Jumbo — suggest the ironic inventiveness of his narrative style. However, Reed is a serious writer. His novel Flight to Canada (1976) is his contribution to the genre of Afro-American slave narratives. Even though the novel draws upon the lives of actual historical personalities (among them, Abraham Lincoln), it departs radically from slave narratives as we know them. Reed's slave escapes by flying to Canada on a jet. He is served champagne as he recounts the story of his travails.

Despite the challenge of postmodernists, other writers continued publishing traditional novels. Eudora Welty's The Optimist's Daughter (1972) is a beautiful, oldfashioned novel containing a hometown, a family, the death of the father, the funeral, and its aftermath. Established writers like Roth, Bellow, and Updike continued writing the kind of books that had made them famous.

More recently some remarkable novels have been written by writers who are more or less traditional in their approach. Of the writers I have read, the following are some of the more talented and promising: Mary Gordon (Final Payments and The Companyof Women); Toni Morrison (Song of Solomon and Tar Baby); Robert Stone (Dog Soldiers and A Flag for Sunrise); David Bradley (TheChaneysville Incident); Ann Beattie (ChillyScenes of Winter, Falling in Place, and TheBurning House); Alice Walker (Meridian and The Color Purple); James Alan McPherson Hue and Cry and Elbow Room); Ann Tyler (Celestial Navigation and Earthy Possessions). This list is, of course, representative rather than inclusive.

The works of Donald Barthelme are not marked by erudition like Pynchon's. Since the early sixties, he has published several collections of short stories, many of which were first published in the New Yorker, and two novels, including Unspeakable Practices, Unnatural Acts, 1968 (stories); CityLife, 1970 (stories); Sadness, 1972 (stories); and The Dead Father, 1975 (novel). Barthelme's fiction concerns itself with the boredom and predictability of modern life. His is an attempt to break out of what he calls the "cocoon of habitation which covers everything if we let it." One of Barthelme's best stories is appropriately titled "Critiquede la Vie Quotidienne." But his varying critiques of everyday life are essentially verbal snapshots. One searches in vain for philosophical meaning. This is because, as Barthelme puts it: "... the literary object is itself'world' and the theoretical advantage is that in asking it questions you are asking questions of the world itself."

The works of Robert Coover and Ishmael Reed are extremely innovative. But both writers make use of familiar forms, materials, and historical characters by radically altering them. The climax of Coover's best-known novel, The Public Burning (1977), is the buggery of Richard Nixon by a character named Uncle Sam. Coover's attitude toward the writing of fiction is dramatically illustrated in his short story "The Hat Act." A magician walks on stage and starts performing magic tricks. The audience laughs and applauds when he is good. But they are easily bored. He must perform one spectacular trick after another or the audience becomes silent or boos. Coover views the writer as a magician who must provoke readers to see the new in the old. In "The Brother," he tells the story of Noah and his Ark from a different perspective. Coover decides to focus on Noah's brother, "a huge oversize fuzzy-face boy," who becomes, alas, one of the victims of the flood.

Now, here are brief summaries of two of my favorites on the list. Final Payments, Mary Gordon's first novel, is a wonderful book. It is the story of Isabel Moore, a good Catholic girl, who devotes a significant portion of her life taking care of her father. Isabel explains:

He had a stroke when I was nineteen; I nursed him until he died eleven years later. This strikes everyone in our decade as unusual, barbarous, cruel. To me, it was not only inevitable but natural. The Church exists and has endured for this, not only to preserve but to keep certain scenes intact: My father and me living by ourselves in a one-family house in Queens. My decision at nineteen to care for my father in his illness. We were in our situation but not unique. It could happen again.

As the narrative progresses, Isabel experiences an unexpected metamorphosis and finds herself involved with two married men. However, she is driven to return to the world of her father to make her final payments.

Toni Morrison (who received an honorary degree from Dartmouth last June) is another talented writer. Her novels scintillate with the bright magic of fairy tales. Tar Baby, her latest book, is at once a love story and the story of a young woman's struggle to find herself. Furthermore, the novel is a beautiful and penetrating story of relationships —Jadine and Son, Margaret and Valerian, Ondine and Sydney, among others. Jadine, a black, cosmopolitan model who studied at La Sorbonne, is the heroine. When we first encounter her, she has awakened from a bad dream. To console herself, she thinks of one of the happiest moments of her life which she had experienced two months before in Paris. With the Caribbean moonlight to enhance her dreamy mood, she recalls how she decided to give a party on that wondrous Parisian day. And she remembers her trip to the Supra Market to pick up a few tasty, exquisite items Major Grey's chutney, real brown rice, tamarind rinds, breasts of lamb, Chinese mushrooms, arugula, palm hearts, and Bertolli's Tuscany olive oil. In a few sentences, Morrison paints a marvelous portrait of Jadine:

If you had just been chosen for the cover of Elle, and there were three counts, three gorgeous and racuous men to telephone or screech up to your door in Yugoslavian touring cars with Bordeau Blanc and sandwiches and a little C, and when you have a letter from a charming old man saying your orals were satisfactory to the committee well, then you go to the Supra Market for your dinner ingredients . . .

Jadine has always been treated royally. Valerian Street, the white millionaire whose family made a fortune selling chocolate candy, is her sugar daddy. Theirs is not a sexual relationship. But here's the irony: Jadine's biological parents are dead. She comes by the largesse of the Streets because her aunt and uncle (Ondine and Sydney) are the Street's loyal house servants. So when Jadine returns from Paris to the Caribbean, she has no qualms about being served by her own uncle and aunt.

Jadine meets and becomes infatuated with Son, a dark, handsome gypsy who hails from a small town in Florida. In her dealings with Son, the emotional pendulum swings between love and hate, repugnance and desire. Eventually they leave the Caribbean and spend an idyllic, romantic sojourn in Manhattan. Then, after some arm twisting, he takes her to Eloe, his hometown. They arrive and she cannot abide it. Shortly thereafter she flees back to Manhattan. When Son returns, she urges him to do something with his life. She tells him to enroll in school and take the LSAT. He says no. One day when he returns home, Jardine is gone. At the novel's end, Son returns to the Caribbean searching for Jadine and for love. But Jadine has other plans; she is high above the Caribbean forest on a flight to Paris.

To return to the question I raised at the beginning. After I have given names and titles and mini-lectures, I am informed that I have excluded important writers; and that none of the writers, including those I have excluded, captures the magic and meaning of American life the way Faulkner and Fitzgerald did. ''TheGreat Gatsby," they say, with a dreamy expression on their faces. I tell them that I share their enthusiasm for Fitzgerald's tourde force and that the green light often flashes in my mind. Finally, I tell them that the writers have to tell their stories in their own ways. As one of Henry James characters said: "We work in the dark. We do what we can, our doubt is our passion and our passion our task. The rest is the madness of art."

Horace Porter is Assistant Professor of Englishat Dartmouth and he also teaches in the AfroAmerican Studies Program. He is presently onsabbatical leave writing a book about theAmerican novelist James Baldwin.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureArtists in Residence

October 1983 By Churchill P. Lathrop -

Feature

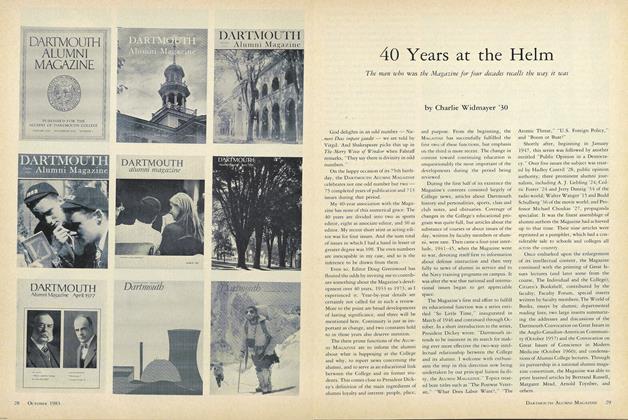

Feature40 Years at the Helm

October 1983 By Charlie Widmayer '30 -

Feature

FeatureRudolph Ruzicka's Two Dartmouth Medals

October 1983 By Edward Connery Lathem -

Feature

FeatureMeet Ted Leland

October 1983 By Brad Hills '65 -

Feature

FeatureThe Widmayer Touch

October 1983 By Cliff Jordan '45 -

Feature

FeatureLessons from the Past

October 1983 By Allen A. Ryan '66

Features

-

Feature

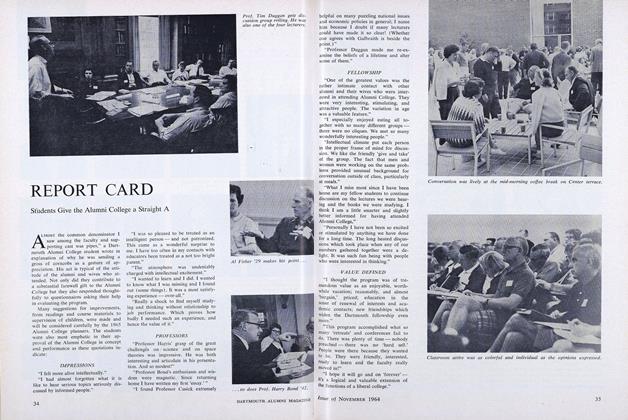

FeatureREPORT CARD

NOVEMBER 1964 -

Feature

FeatureOnce Upon a Time

December 1980 -

Feature

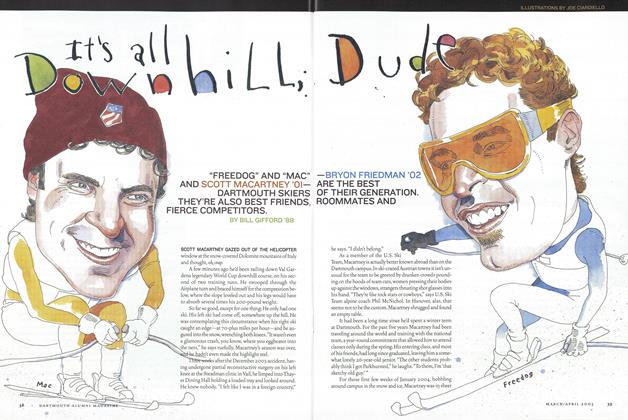

FeatureIt’s All Downhill, Dude

Mar/Apr 2005 By BILL GIFFORD ’88 -

Feature

FeatureBIG JUMP

Winter 1993 By David Bradley ’38 -

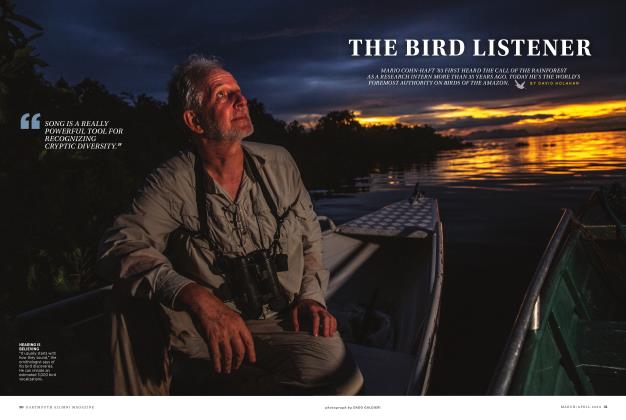

FEATURE

FEATUREThe Bird Listener

MARCH | APRIL 2024 By DAVID HOLAHAN -

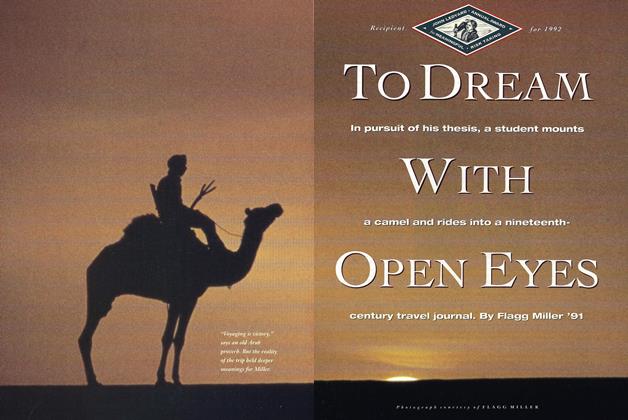

Feature

FeatureTo Dream With Open Eyes

APRIL 1992 By flagg Miller '91