The Navy has invited Dartmouth to invite it back to campus. President McLaughlin passed on the invitation to an ad hoc committee charged with investigating the wisdom of re-establishing a Naval Reserve Officers' Training Corps (N.R.0.T.C.) program at the College. The eight-member committee, chaired by Professor of Religion Fred Berthold, includes faculty, administrative, student, and alumni representation and is expected to report during the winter term.

Dartmouth had an N.R.O.T.C. program for a number of years during the fifties and sixties. The Board of Trustees terminated the program in academic 1968—69 for a number of reasons. Chief among them, according to Berthold, were the incompatibility of R.O.T.C. with a liberal arts undergraduate education, the unsuitability of appointing military personnel to the Dartmouth faculty, and a basic opposition to the policies of the military (especially with regard to the conduct of the Vietnam War).

All three objections were raised again at an open meeting held by the ad hoc committee late in January. Other questions raised by the committee included whether the eight regular curriculum courses and eight naval science courses required by the Navy would put students in the program under an intolerable course overload; whether Dartmouth would be making a valuable contribution to society in training officers in the context of a liberal arts education; and whether Dartmouth should make available to students the two- and four-year scholarships an estimated 20 of them annually offered by the Navy.

Attendance at the meeting was sparse. Some 40 members of the Dartmouth community showed up. The Navy declined to send a representative. The committee opened the discussion to the floor, and Professor of Anthropology Hoyt Alverson reminded the group that the commanding officer of the former program had told the faculty, "As far as Naval R.O.T.C. is concerned, a student belongs to the Navy first, and to Dartmouth second." Another faculty member reported that he knew of three Dartmouth N.R.O.T.C. students who, in the sixties, had been threatened by their commanding officer with negative fitness reports if they attended a campus demonstration. (A single such report, apparently, can lead to immediate expulsion from the program into active service.) Gil Tanis, director emeritus of the Dartmouth Institute, responded that he recalled no disagreement between a Dartmouth R.O.T.C. student and the Navy that had not been resolved "in favor of the lad" and asserted that recalling R.O.T.C. was doing no more than being responsible citizens.

A student asked, "What is liberal arts if it does not include some sampling of what we are facing in the real world?" to which Professor Scot Drysdale of the Mathematics Department replied that the liberal arts, by definition, exclude certain subjects business training, for instance. Drysdale asked the group to consider whether, by analogy, it would invite I.B.M. systems engineers onto the faculty in return for the corporation's founding scholarships. Tom Roos, professor of biology, extended the analogy and asked whether Dartmouth would condone a student's signing a contract that would require sweeping floors at I.B.M. for two years if he had to drop out of school.

A student described the Navy's invitation as government blackmail and censured the Reagan administration for cutting other scholarship funds and then teasing young men and women into the military. Another student urged Dartmouth to find the money elsewhere. A third student, reading from prepared notes, maintained that Dartmouth students have a right to the R.O.T.C. scholarship alternative.

Professor of Sociology Elise Boulding cited her experience in a reciprocal lecturing situation with R.O.T.C. faculty at the University of Colorado. She described R.O.T.C. courses as "indigestible, highly specialized chunks of pre-professional and professional knowledge" very different from liberal arts courses. "They could not easily be integrated into a liberal arts education," she said. "That is not to say that one ought not to have such training. But should we have it here?"

John Lamperti, professor of mathematics, described the question before the committee as first and foremost political. "Most of the Navy is not for defense, but for the projection of power in the far corners of the world," he said. He reminded the group in graphic detail of the extent of the current arms buildup in this country and asked that the committee consider carefully what it will say to the outside world if Dartmouth enters again into a relationship with the military.

Harry Ames '61 of Woodstock, Vermont, a former Dartmouth N.R.O.T.C. midshipman, delivered a prepared speech, with copies. He urged that Dartmouth resume its relations with the Navy, on a "fair, business-like, non-emotional basis."

It was all much the same as before, except for an innovation urged by sociologist Boulding. "There is a desperate need in the world," said the professor, "for people trained to work at the international level in non-military problem-solving under conditions of high stress. That is what we need courses in. Let us move the whole question over. Don't let's do what we are not wellequipped to do. Don't let us try to train military officers. Let us train civilians in other ways of solving conflict, to serve the international community."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureWhat Is Success?

March 1983 By E. R. (Skip) Sturman '70 -

Feature

Feature"Long John" Wentworth, 1836

March 1983 By Dirk Olin '81 -

Feature

FeatureYou know, what's his name . . ."

March 1983 By Nardi Reeder Campion -

Feature

FeatureOff and Chopping

March 1983 By Jean Hanff Korelitz -

Article

ArticleSetting the Record Straight: A Senior-Year Perspective

March 1983 By Libby Schmeltzer '83 -

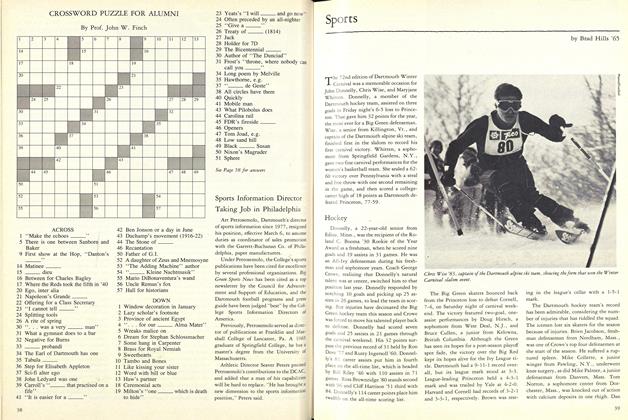

Sports

SportsSports

March 1983 By Brad Hills '65

Article

-

Article

ArticleREPORT ON THE FRATERNITY SITUATION

August, 1914 -

Article

ArticlePROF. MATHEWSON APPOINTED TO PERSONNEL BUREAU

MARCH, 1927 -

Article

ArticleSalzedo-Ehrhart-Harrison

APRIL 1930 -

Article

ArticleHeads Business Group

June 1944 -

Article

ArticleHarvard 26, Dartmouth 19

December 1952 By Cliff Jordan '45 -

Article

ArticleThe Campaign Gets a New General

FEBRUARY 1994 By Heather Killebrew '89