FROM THE MOMENT SHE SAW HER FIRST RACING SHELL AT DARTMOUTH, JILL FREDSTON WAS ADDICTED.

I WAS WALKING ACROSS THE GREEN as a freshman when I saw my first racing shell, suspended on saw-horses so thin it was translucent. The hull was more than 60 feet long, with eight sets of sliding seats, one right behind the other. I was no longer the scrawny kid given doughnuts at camp as part of a weight-gain program, but at 5 feet, 8 inches I was still made up mostly of sharp bones and right angles, with a strength born more of determination than of mass. Though team members attempting to recruit passerby of significant size overlooked me, I was hooked.

Crew boats were nothing like I'd ever rowed. The "eights" were water borne rockets—capable of exhilarating speed. Learning to use my legs, arms and back to drive a 13-foot oar through the water while rolling back and forth on a little wooden seat was like learning to walk again. The unified effort of my body had to be carefully synchronized with that of seven other women, while we were steered and encouraged by a small coxswain with a disproportionately large voice. When we matched each other perfectly, which didn't happen often enough to take for granted, we had "swing." Then the boat would surge forward, trailing a symmetrical signature of whirling pools from each oar.

Too frequently, swing eluded us. In our first race, we lacked the discipline to keep our hands steady, so we kept throwing the boat off balance, causing one unfortunate after another to "catch a crab"—get her oar stuck in the water. The veering boat would slow, sometimes to a stop, the coxswain would rage and we'd thrash like dying fish before getting the boat back on course and up to speed. Only because the five other teams were similarly inexperienced did we eke out a win. In our post-race exuberance, we drifted past two sets of warning buoys and nearly went over a dam in our borrowed $8,000 shell. It was an inauspicious start to a magnificent season in which we reigned undefeated until the final championships, when we faced corn-fed mesomorphs from Wisconsin.

My memories of that race are ragged. Someone crabbed at the start and we skidded backwards, into water abandoned by the other boats. I remember the coxswains disembodied howls coming through a speaker under my seat, exhorting us to pull as we never had before. And we did. It might be the only time in my life that I haven't held just a little bit of myself in reserve. "I HAVE THEIR SEVEN!" the voice shrieked as we drew up to the stern of the first boat ahead. "NOW GIVE ME THEIR FIVE!" Foot by foot, we clawed past the rower in the bow seat. One boat behind us, four still ahead. We became one long, gasping body with 16 muscled arms and knotted calves. Can't pull harder. Have to. No. Must. Beyond logical thought, out of air, two boats behind now. Nothing but the voice, exploding waves of pain and a rising roar of spectators. Spots in my eyes, dead legs, lungs sucked dry, heart splitting my chest, searing fire in my back. Breathe. Can't. Must. Two more boats fell prey. The voice thundered. Only one more boat. Quit. Can't. Breathe. Can't. Must. "LAST TEN STROKES!" The voice promised and counted them aloud like drumbeats. I emptied the last fragments of myself into my oar. Die. Soon. "FIVE MORE!" I had nothing left but a silent scream. We crossed the finish line and I slid into darkness, into a quiet that even the voice couldn't penetrate.

Consciousness came with the sounds of my teammates vomiting into the water. The coxswain, a woman again, explained that-it was a photo finish, a matter of inches being decided upon by the officials. Eight bodies now instead of one, we lay back against one another's numb legs, swilling air, unable to ignore the pain, which was as excruciating as frozen fingers beginning to thaw. We managed a clumsy rag-doll-like row to the dock, but the world was a grainy television screen, a fuzz of speckled gray. Landing, I leaned in the wrong direction, fending off into harm- less air rather than reaching for the wood float. The rest of our team poured onto the dock, knowing that we were too far gone to lift the boat out of the water and over our heads by ourselves. First place was awarded to the mesomorphs, but surprisingly, that was of little matter.

I didn't row all four years at Dartmouth, partly because foreign study kept me away during several semesters of racing, but mostly because I thought it demeaning to be in any boat other than the varsity and was afraid to take that chance. Accustomed to having most things come easily, I hadn't yet learned the discipline of total commitment. Rowing at very competitive levels means at least three hours of training every day. It means long hours in the weight room. Despite the coach's constant reminders to have "fast hands" or a "quick catch," my rowing stroke never seemed to achieve a level of perfection. And my eyes were a problem. Dur- ing practices especially, they kept wanting to drift out of the boat, and around each out side bend in the river rather than staying drilled into the back of the woman in front of me. I was discovering that at heart I am more of an endurance rower than a sprinter. For me, rowing is about more than moving fast. It is about going somewhere.

Excerpted from Rowing to Latitude: Journeys Along the Artie's Edge by Jill Fredston. Published by North Point Press. Copyright© 2001 byJill Fredston. All rights reserved.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureThe Gatekeepers

November | December 2002 By JACQUES STEINBERG ’88 -

Feature

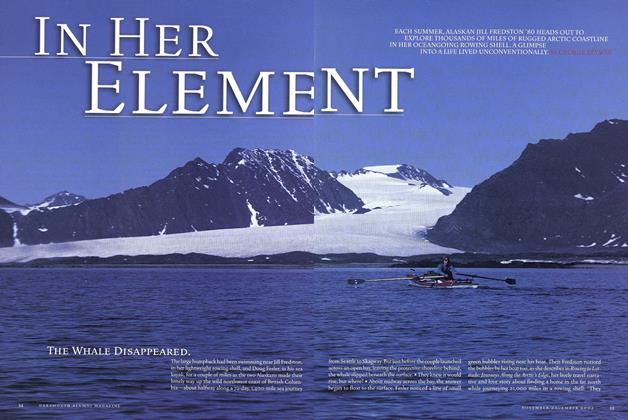

FeatureIn Her Element

November | December 2002 By GEORGE BRYSON -

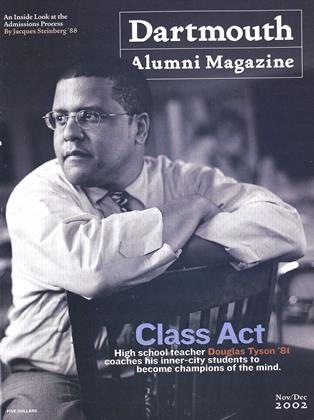

Cover Story

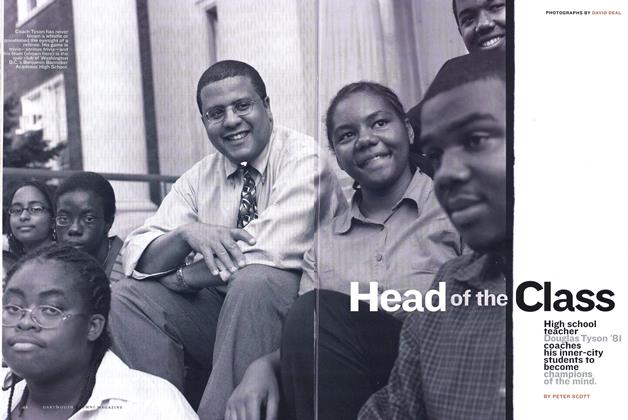

Cover StoryHead of the Class

November | December 2002 By PETER SCOTT -

Faculty Opinion

Faculty OpinionThe Iraq Question

November | December 2002 By Daryl G. Press -

Classroom

ClassroomThe Art and Science of Group Dynamics

November | December 2002 By Karen Endicott -

Outside

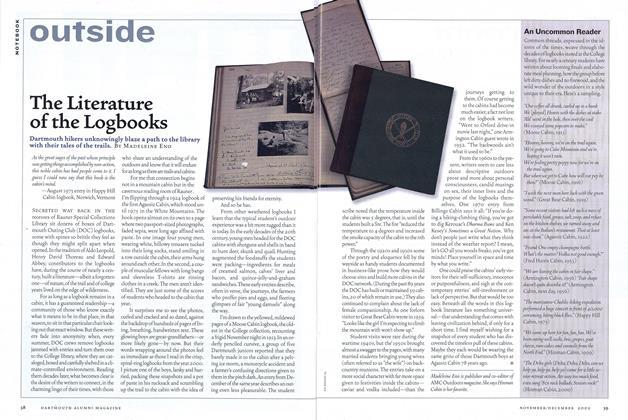

OutsideThe Literature of the Logbooks

November | December 2002 By Madeleine Eno

Article

-

Article

ArticleFIRES IN HANOVER KEEP DEPARTMENT BUSY

April 1926 -

Article

ArticleThe Seniors Confess

AUGUST, 1928 -

Article

ArticleFaculty Articles

June 1961 -

Article

ArticleA Lesson in Impermanence

MARCH 1999 By CASEY NOGA 'OO -

Article

Article1901-1905 Boston Dinner

June 1945 By Dave Austin '04 -

Article

ArticleVery Green Grass

December 1975 By JACK DE GANGE