A great deal of public concern and media attention has focused recently on the issue of the nuclear armaments race. An attendant fear is spreading throughout this and other nations that the world may be destroyed in our lifetime by these weapons. The fear stems from the perception that the potential of their use is escalating and is generated by thinking which affirms the necessity for their development.

Armistice Day events and the more recent Ground Zero Week activities have been held around the country over the last two years, primarily on college campuses and in university-centered communities. One may well ask what position, if any, our educational institutions should take in the face of this issue. The prospect of nuclear annihilation is a concern affecting us all, even unto our very hope for survival. It was not so long ago that widespread discussion sprang up on college campuses about the Vietnam War. Will the arms race become a similar issue in the 80's?

Meanwhile, there are those who remain unconvinced that we are so close to doomsday. They ask: Are recent times as unprecedented historically as we are often led to believe? This age may indeed be curious, but is it really any more precarious than eras faced by previous generations? And after all, should not colleges and universities be about the business of educating people rather than contending about issues of world conflict, power, and the prospect of war?

Over a year ago, in September 1981, such questions came to the forefront at Dartmouth at the traditional opening Convocation. In his remarks, Leonard Rieser, former provost, cited the following quotation from a 1950 Convocation address by President John Sloan Dickey. In Dickey's mind the major concerns for the stability of the world order and continued human survival at mid-twentieth century were: "First, the opening of the widest chasm of ideological conflict the world has ever known. Second, the fantastic increase in the destructive power of men as contrasted with the relatively static state of the moral and political controls governing such power. Thirdly, the rise of the mass media of communication, making the emotions and minds of millions the constant prey of the few."

How much things stay the same howlittle they change. In light of thirty intervening years, Dickey's words appear less prophetic than simply a routine statement of the way things were. However, in all three of the areas mentioned there has been movement toward a heightening of the problems, especially concerning our de- structive power." As the president of a major institution and leader of its community, Dickey brought forward his thoughts about the precariousness of human existence for discussion and reflection. Concern with these issues seemed to have had a clear place in the life of the College; the context was appropriate.

Last spring, Dartmouth's board of trustees expressed a desire that the institution explore ways in which concerns raised by the arms race could be addressed. Without taking sides, the board courageously set itself by the side of John Dickey in assuming that a college is indeed a place for discussion of such a pressing issue of the day. Other institutions of higher education are taking similar initiatives. At Dartmouth this has already led to a variety of activities and programs. Among these are a course, the Senior Symposium entitled "Nuclear Arms: Challenge and Choices," and a scheduled "Ivy League Conference: Issues of Nuclear Arms" initiated and organized by Dartmouth undergraduates. In spite of all this, there remain skeptics who would criticize such a position and raise the question, "Why should educational institutions be moved in such a manner?" It is this question which must be addressed.

I would contend that discussion about the nuclear arms race .should be viewed as no less appropriate within college and university communities than within the medicalcommunity, where voices have already been raised. Groups such as Physicians for Social Responsibility have declared the prospect of nuclear war to be a severe medical problem, a nightmare labeled by some as "The Last Great Epidemic." These physicians, scientists, and other professionals believe they have a public obligation to be on record regarding their inability to cope with the medical and health consequences of nuclear war. Similarly, the life of the mind, the nurturing of which is the basic raison d'etre of educational institutions, would be threatened by nuclear welfare. Are those of us who have vocations in the temples of learning in any better position than our medical counterparts to cope with the consequences of such destruction? The role of educators and of the educational endeavor is to stimulate knowledge and learning, preserve and protect the value of intellectual pursuits, and exPlore and care for the legacy of thought mherited from our predecessors.

Ponder the blow that would be dealt to knowledge and learning by a nuclear ex- change, even assuming the existence of survivors to pick up the pieces. Library collections reduced to ashes, every copy of some major works obliterated, original manuscripts and works of art forever lost and computer memory banks destroyed. Quite literally we would be blown back beyond the Dark Ages, and so much more because many learning tools and resources could not be recovered. Thousands of years of human experience, the quest for knowl- edge, the pursuit of truth, would be gone for all time. Educators, as individuals or collectively have as much reason as any professional group to be concerned and on the public record about the devastating results of nuclear holocaust. In this vein, the American Academy of Religion has re- cently made such a statement reflecting their concern.

Colleges and universities should stimulate and initiate dialogue about issues of nuclear armaments and world peace. The lead taken by Dartmouth and others should be followed. There exists a common, cross-cultural, and trans-national heritage to be preserved and maintained. We ought to be involved where a threat is posed to truth, beauty, music, art, and the totality of human experience. It is possible that before too long leaders of the business world will see the prospect of nuclear war to be harmful to business and thereby raise their opposition. Must those of us in education wait for such a cue before asserting the same from our perspective?

The programs and activities of past Armistice Days and Ground Zero Weeks stand as a testimony to the role that can be played. Given the complexity of the nuclear weapons issue, we need to provide similar forums for discussion. At the same time, ongoing research, study, and scholarship on various aspects of the arms problem and possibilities for peace-making must be encouraged. Our educational institutions are centers for thinking, and clearly the nuclear proliferation problem is one demanding the utmost thought and creativity. One possibility would be to suggest that incoming students read Jonathan Schell's highly praised The Fate of theEarth or any of the similar publications now emerging. Then during orientation week and throughout the year small group discussions and colloquia could be held concerning its implications.

Teach-ins were an educational tool used in the 1960's; however, as the events of those days unfolded, a deep-seated polarization infected college and university communities as well as society as a whole. We must learn from experience and avoid polarization in our discussion of the arms race. This means maintaining free dialogue and speech, providing access to divergent viewpoints, and allowing for debate among them. The basic question is: will the students we educate have the opportunity of a full lifetime in which to continue the eduational process begun during the college years, sharing what they learn with and for others? Or will their world be brought to an end by a terrible unleashing of unimaginable destruction?

A year ago I asked some first-year students to respond to the question: "What is your greatest hope for the four years of the college experience?" A number of them replied they hoped to arrive at graduation nothing more than happy. Was this hope based on a feeling that unhappiness was a great likelihood? Did they fear a world gone mad, disintegrating around them and taking them with it? I am not certain; however, I remain puzzled by what is a simple and personal, though simultaneously a somewhat hedonistic and selfcentered, goal of coming through college "happy." Happiness would not top my list of hoped-for accomplishments in college.

Maybe these are strange times indeed. The young people to whom we educators have committed ourselves are searching. If the above-mentioned students are indicative, there is searching for happiness and undoubtedly for other things as well. Maybe they suffer from a low-level but nonetheless significant anxiety about the human prospect. Such anxiety no doubt comes in part from fear of our inability to control the dangers developing in our world. In the face of such a challenge, let us not leave a legacy of having stood idle while the very heart and mind of civilization was erased. Let us rather bear witness to the importance of education. Let us come to grips with the reality that all we have inherited from previous generations, and our very lives, may be in jeopardy if we either believe we have nothing to say or refuse to be heard.

steven Nelson is Director of the Collis CollegeCenter.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

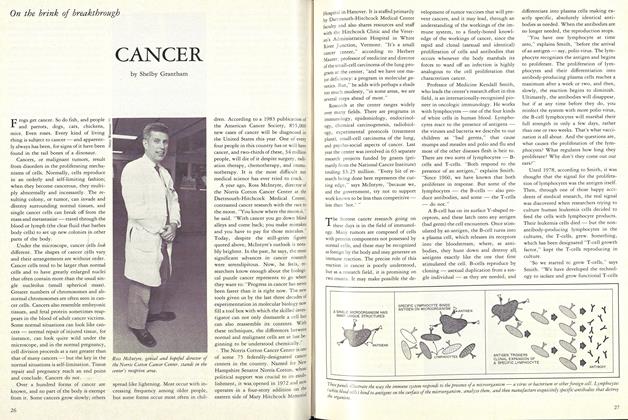

Cover StoryCANCER

April 1983 By Shelby Grantham -

Feature

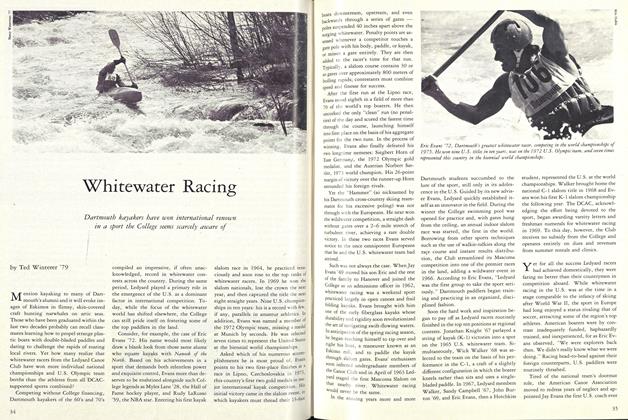

FeatureWhitewater Racing

April 1983 By Ted Winterer '79 -

Feature

Feature1340 on your radio dial

April 1983 By John May '85 -

Sports

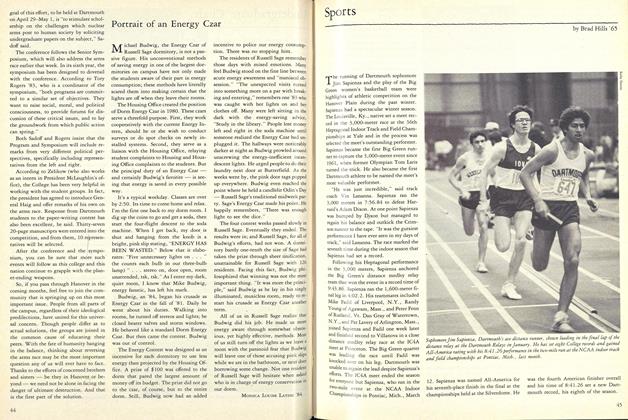

SportsSports

April 1983 By Brad Hills "65 -

Article

ArticleRhodes Scholar

April 1983 By Steve Farnsworth '83 -

Article

ArticleA Universal Concern

April 1983 By Steve Famsworth '83

Stephen J. Nelson

Article

-

Article

ArticleWINTER TRACK WORK

-

Article

ArticleTicknor Club Marks Its 50th Anniversary

June 1951 -

Article

ArticleForeign Fellowships Open

October 1951 -

Article

ArticleHow to Speed Read

JANUARY | FEBRUARY 2016 By —Gayne Kalustian ’17 -

Article

ArticleGreen & Gold

NOVEMBER 1997 By Abigail Klingbeil '97 -

Article

ArticleTuck School

MAY 1969 By BOB KIMBALL T'48