The Rassias method for language instruction works for those who survive

"Wir sind an Dartmouth und wir freuen uns sehr," cried the young man. "Now come on."

"Sehr," he shouted. "Sehr," ventured a few.

"Freuen uns sehr," he pleaded. "Freuen uns sehr," responded a few more.

"An Dartmouth und wir freuen uns sehr," he cajoled. "An Dartmouth und wir freuen uns sehr." Better now. It was coming.

"Wir sind an Dartmouth und wirfreuen uns sehr," he urged. "Wir sindan Dartmouth und wir freuen unssehr" we shouted back in near unison. Very few of us knew what we were shouting but we were getting the idea. Without knowing it (and that was part of the idea) we had uttered a complete German sentence.

"We are at Dartmouth and we are having a good time." True enough. It was a lovely Sunday evening in early July and some 240 Dartmouth alumni and friends were gathered for a barbecue under the green and white tents so familiar to reunions and football games. But we were not there for hard drink or easy camaraderie. We had come to Hanover for ten days of foreign language training the second annual Dartmouth Alumni Language Program (Alps).

The young teacher's assistant in German who pounded the sentence home had given us a foretaste of what we could expect in the 80 hours of classroom time ahead of us . . . intensity and relentless drills and not letting us off the hook until we got it right in French, German, Italian, or Spanish.

Then the Beast, the Madman, the man my three-year-old, rapt from his spell, came to call Garbage Face (a Sesame Street connection, my wife thought), came on stage to introduce the metaphor. John A. Rassias, director of Language Outreach Education at Dartmouth, went into his act.

Many of the Alpinists, as participants in the program are called, already knew a little about this controversial professor of Romance languages. They either had caught him on 60 Minutes or The Today Show or read about him in Time, The New YorkTimes, Smithsonian or any one of dozens of other publications. Rassias was, they knew, Dartmouth's hottest property. He had been lionized as an educational innovator of the first rank, as a revolutionist even. He also had been criticized as an educational cult figure, one who had fouled the sacred shrine of academia with showmanship and emotionalism. Nonetheless, Rassias and his method for teaching foreign languages have reversed the trend of disinterest and neglect in language studies. He has actually taught Americans, notoriously one of the most monolinguistic people in the world, how to speak a foreign language and enjoy it at the same time.

Under the tent and in the dramatic, 200-volt language that is his signature, Rassias promised us that we would move "at a blistering pace." It was a promise he kept. Foreign language was "to penetrate the pores," he said; we would be "molded in the heat of love."

The stocky, smoldering ex-Marine, a man who is as much at home with the teachings of Vince Lombardi as he is with those of Rabelais, prowled the tent insisting, in effect, that we were not sensitive, not human enough but that learning a language his way would help correct that.

"I hear and I see and I remember and I do and I understand," Rassias quotes the philosopher. He is on his knees now, his hair rumpled, his baggy pants drooping down by the moment, his dark eyes careening in his protean, pugilistic face.

The neatly dressed, middle-aged woman on whom Rassias is now sweating, is laughing through her obvious bewilderment and discomfiture. She no doubt is asking herself what many under the green and white tent are asking themselves: "Is this guy for real? His act is a zinger, but what is this savage Greek doing tearing off his clothes at a proper place like Dartmouth?"

What John Rassias appears to be trying to do at Dartmouth is to humanize it through the vehicle of language instruction. "If you can't humanize the place," he says, "then shut it down." At an institution where academic instruction has always come first, Rassias stresses the education of the emotions.

"Emotions are banished at Dartmouth," he told me in an interview. "This is an intellectual organization where emotion is viewed as anti-intellectualism. . . . But if the kids are to become whole, they must become humanized. They are emotional creatures."

So Rassias, the man who insists that teaching should be "violent," the man who has stripped travel posters from classroom walls and replaced them with pictures of starving children, uses language instruction as a club. With it he tries to beat awareness and sensitivity into his students.

"Teaching should be like the fire of hell," Rassias once told a reporter, " . . . burning away the inhibition that blocks communication and the preju- dice that prevents sensitivity."

Arid he tells us, winding down under the big tent, that "if you don't become like a child, you'll never learn a language."

These were, to say the least, improbable views for a full professor at Dartmouth College. More than one Alpinist wandered out of the tent that first night wondering what the hell they had gotten themselves into.

Michael, who had just dashed a chair against the wall for an attention-getter, was now on the floor of the tiny, hot basement classroom doing push-ups. And he shouted at me that he was going to keep doing push-ups until I got the third person plural of "faire" just right. He was really struggling, this gung-ho teaching assistant, when that nice Vassar graduate, a librarian from somewhere in New Jersey, bailed me out again. Rassias had said that first night that "mistakes are the building blocks to perfection." I

was beginning to think that my primary role in Tunis, my advanced intermediate French section, was to help make my classmates perfect.

I had decided to come to Alps for several reasons. I studied German at Dartmouth during the early '6os and spent part of my junior year abroad in Germany. I was interested in comparing the analytical, intellectual approach to foreign language that we took back then to the radically different methods Rassias began introducing to the College in the late '6os.

When I got off the plane in Frankfurt in the fall of 1964, I had read Goethe and Kafka closely but couldn't find my way through my inhibitions with the German tongue to even get to the toilet. Rassias promised even a beginner "street fluency" in a language within ten days.

I returned to Germany after my college days and in time learned to speak German with some fluency. French, however, was another matter. I had acquired a usable but rough French during a winter of ski bumming in France 12 years ago. I chose to study French at Alps because I figured I could make nothing but progress in that language. My willingness (if not my readiness) to speak French always had been high, and based on that, I was placed in Tunis, the second most advanced section. (All sections were named after a city in a French-speaking country.)

In Tunis, as throughout the program, there was a good balance of sexes and ages. It certainly was a more diverse class than I ever attended at pre-coeducational Dartmouth. There was, however, little diversity of class. Alpinists were people who could afford up to $695 for the ten-day course and whose notion of a vacation was a language slugfest, a heavy dose of selfimprovement.

Reasons for attending the language program were as diverse as the Alpinists. They ranged from a desire of one, a mountain climber, to be able to discuss climbing paraphernalia in German to that of an elderly alumnus of French extraction who was preparing himself for a trip to France to track down his roots.

One Italian student said she was taking the course merely to see if she could get through it; she needed a confidence builder. And there was a mechanical engineer with barely intermediate abilities in French who would be teaching in Lausanne in the fall. His prospects for success demanded that he speak better French.

In Tunis, Mark said he wanted to refresh the French he learned at Dartmouth and that he simply was drawn to rigorous experiences. He had just returned from three weeks of hiking in the California desert. The calluses on his feet were as thick as nickels. David, a young Philadelphia lawyer, was scrubbing up his already decent French for the trip to Blois that Alps had organized as a sequel to the training in Hanover. Marian, the Vassar librarian, had enrolled in order to share the experience with her teenage daughter, who was toiling away in Paris, an intermediate group.

Beverly, a teacher of introductory French at a Maine high school, was there simply to become a better French teacher. Her enthusiasm for French culture was bubblingly evident. She wore a tiny picture of Andre Malraux strapped to her wrist.

And then there was Martine, a teenager from Dallas who had been sent to Alps by her parents. Her mind cleaved more toward David Bowie than the imperatif. She soon quit Tunis for Montreal, one city less advanced.

In Tunis' tiny basement room in French Hall we sat and the teachers came at us in waves from 8 a.m. to 5:10 p.m. every day. The mere recitation of the schedule will perhaps give you the idea. The first class each day was a socalled "Master Class" given by a Master Teacher, one of Rassias' handpicked disciples. In this class, all the material to be covered for the day was introduced in French, of course. Then came three consecutive drill classes before lunch. Drill classes were conducted by Dartmouth students or recent graduates, all of whom had been highly trained in Rassias' methods.

After lunch, munched in French in Thayer Hall, it started all over again. There was another Master Class, followed by tow drill sessions and then a review Master Class to insure that we hadn't missed anything during the day. After dinner (the cuisine, alas, was not French), there was a cultural hour from 8 to 9. These sessions featured more intensive language training but of a more diverting nature.

In short, we were inundated with foreign language. There was no time, no energy to think of anything else. For ten days, language came at us as relentlessly and regularly as a Bay of Fundy tide.

Of course it is how the language is served up that distinguishes the Rassias approach from more conventional foreign language programs. Each Master Class and drill session pushes the student into total concentration and receptiveness. By merely submitting to the process, the student is virtually assured of making substantial progress.

Rassias' insistence on small classes (no drill class had more than six students) in small, no-frills classrooms created an atmosphere of charged intimacy. Each hour contained a carefully rehearsed presentation of material which, at all but the highest levels, consisted of the basics: grammar, vocabulary, and pronunciation.

The 50-minute drill classes were conducted at a furious pace. Everyone was expected to respond in French up to 60 times per session, but we had to be ready to respond to everything. Instructors were trained to look in one direction at a student while pointing at another student. And it was the student at the end of the snapping finger, not at the end of the gaze, who was on the spot.

Mistakes were tolerated but quickly corrected. If one's answer was grammatically or phonetically wrong, the instructor kept snapping those fingers until someone else got it right. Then everybody who was wrong had to repeat the word or declension or phrase until everyone got it right. Finally, the entire class repeated the drill in unison.

These are,brilliant little teaching devices calculated to keep students on a fulltime hook. They are at the core of lamethode. One must, in effect, be ready to answer every drill question up to several hundred per session whether he is snapped at or not. In this way, language is burned into one's brain.

Rassias' techniques would be downright abusive were they not tempered by humane, often humorous embellishments. Correct answers were rewarded with a "tres bien," a smile and sometimes a kiss and a hug. Makers of big mistakes routinely were "blown up" in a tension-releasing little skit. The pattern of instant reward and punishment supported the childlike level of receptivity and uninhibitedness we were expected to attain.

The effect the neatly contrived, highly-structured and unrelenting bombardment of language had on us was unmistakable. One student in Tunis, a Smith graduate and mother of a Dartmouth alumnus, began the course all agog. She would giggle distractingly when she did well in a drill and would often argue strenuously when she goofed. After a couple of days, I noticed she had quieted down remarkably. Her eyes had taken on the glaze of fatigue and shellshock that the eyes of many students had taken on. She no longer was resisting or debating like an adult. She was absorbing still eagerly but almost as if in a trance.

Rassias once told a reporter from Time that "if you want to teach, you must be willing to walk out of class exhausted." He expects his students to exhaust themselves, too; it is part of his strategy to empty them of customary inhibitions and resistance.

One afternoon about five days into the program, I was grinding my way through an intensive drill session. The tricky little y in French was being batted about the room like a ping pong ball. Suddenly I realized that the little phrase il y a comprised my entire mental world. I had no energy for, and no interest in, anything else. Il y a had become a bright linguistic bauble, the transfixing rubber ducky in my bath. I saw that I was taking in language without thinking about it. At that point, I sensed that I had been "broken" and I acknowledged the power of Rassias' methods, as he once described them: "to dynamite raw language into people."

On numerous occasions I've herded initiates into the intense heat of the wood-burning sauna bath I built on my Maine homestead years ago. I've baked with them in 230 degree heat for about ten minutes and then asked them, "What are you thinking about?" If they are able to answer at all, they groan "Heat!" Alps is a piping hot sauna bath of language.

And there is a special, almost wondrous attraction in the extreme nature of what Rassias termed a "Camelot experience within Dartmouth." Alps provides a surefire way of shedding for a time the exigencies of being an adult. Alps is a kind of relief. My wife, who studied Italian for the last three days of the program, caught on quickly. "It's all so wonderfully simple," she said. "All you have to do is worry in Italian."

It is difficult to measure your own progress in a foreign language. Others may do it for you. When I got home, I talked with an old friend who had skied with me through the winter in Val d'Isere 12 years ago. We broke into French and he started laughing. "You know, "he said, "this is the first time I've ever been able to understand you." Coming from Marty, this was a great compliment.

Even during her short stay, my wife made great strides in Italian, a language and culture she loves. She has enrolled in Italian classes at a nearby college and has a high stack of Italian books at her bedside. I'm checking out the shortwave radio market so that I can tune into Radio Paris and Radio Luxembourg on those cold, clear winter nights. You see, we are both getting ready for Alps III.

I had come to doubt that I ever would have a compelling reason to return to Hanover. I gave up on the football games and reunions years ago. The Alumni Language Program changed that. I suspect there are a great number of Dartmouth alumni who, indifferent to rallies and reunion tents, would return to Hanover on a regular basis to refresh and continue their education through programs as individual, refreshing, and effective as Alps. W

Upper left: Author Jack Aley looks worried as Prof. Rassias stares at arm'slength. To Jack's left is Muriel B.Sheppe, mother of Richard '73 and Daniel Sheppe .'75. In between is ThomasHancock '71, flanked by Mark P. Snyderman '79. Upper right: It's beginningto come clear now, thinks Pam Crisafulli, daughter of Stephen Crisafulli '61Above: Voila! The ultimate reward ahug from the "savage Greek" himself.

Apprentice Kerry Osborne (kneeling) queries Richard Shaw '39 as Bruce Rogal '50 and Gail Kraidin (wife of Martin Kraidin 60)look on. Informal settings such as this give classes a "real-life" atmosphere which supplements regular classroom situations.

Prof John Rassias beams with delight at graduation ceremonies as Master TeacherJacqueline de la Chapelle-Skubly hands out the distinctive Alps hat. Was it worth itall just for a piece of paper and a hat? You bet.

Jack Aley '66 is a journalist living inBrunswick, Maine. He spends most ofhis time on a 30-acre wood lot gardening,, and is currently building his ownhome. His interests in language werekindled during his undergraduate daysat Dartmouth.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureShaping Public Policy: The Washington Internship Program

March 1984 By Frank Smallwood '51 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryA New in the Neighborhood

March 1984 By Debbie Schupack '84 -

Feature

FeatureThose Championship Seasons

March 1984 By Brad Hills '65 -

Article

ArticleThe Price of Art

March 1984 By Monica Louise Latini '84 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1963

March 1984 By Harry R. Zlokower -

Class Notes

Class Notes1947

March 1984 By Ham Chase

Features

-

Feature

FeatureMEDIA MONSTER: The Rise of Rankings

Nov/Dec 2000 -

Feature

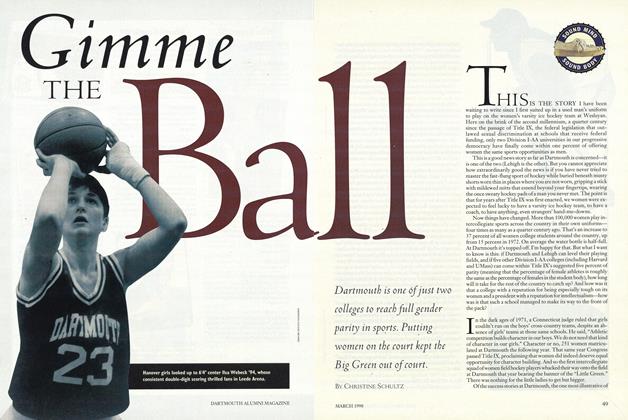

FeatureGimme the Ball

March 1998 By Christine Schultz -

Cover Story

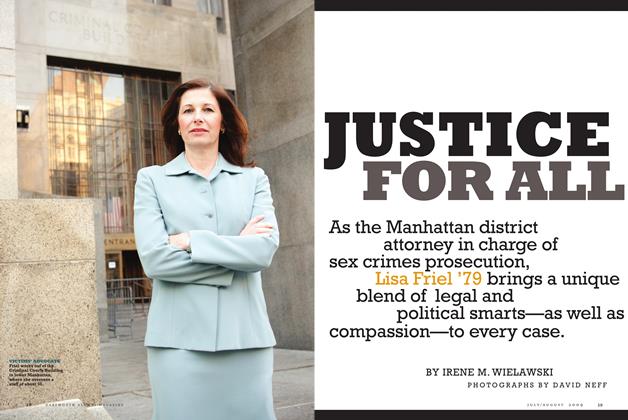

Cover StoryJustice for All

July/Aug 2009 By Irene M. Wielawski -

Cover Story

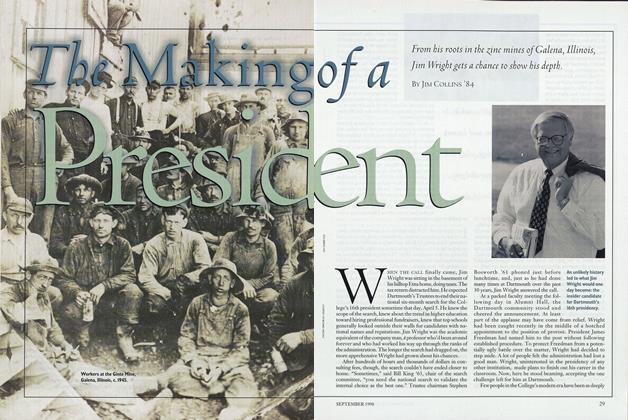

Cover StoryThe Making of a President

SEPTEMBER 1998 By Jim Collins '84 -

Feature

FeatureTeaching at a Communist University

JUNE 1971 By NOEL PERRIN -

Feature

FeatureQuebec in the Modern World

JULY 1964 By THE HON. JEAN LESAGE, LL.D.