Love and lore of geology at Dartmouth bring 140 "rocks" majors back to Hanover

It is Mud Season. It is not a good time to be out in the fields looking at rocks. But that means it is a good time - due to the lull in their own field work - to bring a group of geoscientists back to Dartmouth. The first weekend in April found more than 140 graduates of the College's earth sciences department returning to Dartmouth for a myriad of activities - from evaluating the curriculum to evaluating the life of a geologist - under the auspices of a weekend-long symposium entitled "A Gathering to Celebrate the Excellence of John B. Lyons and Richard E. Stoiber." Lyons and Stoiber are both senior earth science professors (the latter a professor emeritus as well as a 1932 graduate of Dartmouth) to whom the department's alumni feel especially indebted.

The weekend began on Thursday with a field trip exploring the granite of New Hampshire. The rest of the weekend included lectures and panel discussions on the. state of geology, as well as opportunities to pay tribute to Lyons and Stoiber, and, of course, time to socialize. "We had to make it short enough so that people could afford the time," explained Randy Spydell '73 (and A.M. '76), "but long enough so they'd have an excuse to come."

"The symposium was not put on by the geology department," noted Richard Birnie '66 (and A.M. '71), an associate professor in the department and the Hanover connection for the organizers of the weekend. Rather, it was an alumni effort - conceived, organized, and run by former undergraduate and graduate students. Just like the participants in the symposium, the weekend's organizers spanned the country. Sam Adams '59 was the symposium's originator and a key organizer, while his wife Nancy, along with Birnie's wife Pieter, coordinated spouse activities from Etna. A couple thousand miles away in Denver, Colo., Spydell was the primary contact, the one "whose signature was on the letters," although the letters were a group effort. Lan Lange '62 completed the connection from Missoula, Mont. Also instrumental were Diane '74 and Dennis '72 (and A.M. '74) Nielson from Salt Lake City, Utah, who compiled the questionnaires which were sent out to the College's 859 earth sciences alumni. (Of the more than 300 respondents, 72 percent are employed in jobs directly related to geology and another 14 percent reported having jobs in fields at least indirectly related to geology. Nearly all of the respondents, 96 percent, said they are satisfied with their chosen occupation, and 67 percent felt that their salary adequately reflects their value to their employer or society. The largest chunk of those responding to the questionnaire, about 42 percent, said they had jobs in industry, 24 percent in education, and 12 percent in government.)

The symposium had a unique flavor as far as College events go, for its constituents were drawn back both by Dartmouth and by geology. "Love and respect - that's what this weekend is all about," said Larry Dingman '60 at the closing banquet, while remembering Professor Andy McNair, who, before his death, was a colleague to Lyons and Stoiber as a senior professor in the department. The love and respect are three-fold: for Dartmouth; for geology; and for Lyons and Stoiber.

The Dartmouth connection is the most obvious one. Stoiber conjectured, "If you had this in Cincinnati, I doubt that as many people would have come. For some unknown reason, all those people wanted to come back to this body called the geology department at Dartmouth. Who knows, maybe it was to see their old dorm room. But they all came back." He continued, marveling at a loyalty to Dartmouth that spans classes from '31 to '85: "They can whip up classes [at reunions] to get money, but it was amazing that we could pull off this unit of more than 50 classes."

The geology connection was also strongly felt. Dave Merritt '71 (and A.M. '76) began his Friday afternoon lecture on water resources by announcing, "It's good to be back with a group of geoscientists." During his lecture on the minerals industry, Geoffrey Snow '55 quoted from a speech given by John Sloan Dickey when Snow matriculated: "Geology is the most liberating of the liberal arts." Snow explained how geology allows man to understand both the earth and man's niche on it, and he and many other speakers in the symposium urged responsibility in promulgating that knowledge. Nancy Grindlay '83 said, "This isn't like a class reunion. They're professionals. Geology is their life." Although the participants did range in professions from geologist to lawyer to stockbroker, they all shared a passion for geology, born in their undergraduate or graduate school days. So there was nostalgia like that of Dave Duane '56, who began his Friday talk on the oceans industry by assuring his colleagues that he still has his hand lens from Mineralogy 15 - which he took 30 years ago.

There was also a visible sense of loyalty to the graduate program. Of the core organizing group's six members, all received bachelor's degrees from Dartmouth and all but one received a graduate degree from what Stoiber referred to as "this university called a college." Birnie went on to praise the continuing contribution of the earth sciences department's graduate students to both the faculty and the students. "They are an intermediating bridge between the faculty and the students and also serve as role models for the latter. In the questionnaires, many alumni illustrated that the graduate students had an impact on their education." At present, the department has about 60 undergraduate majors and about 20 graduate students (roughly two-thirds in the master's and one-third in the Ph.D. program). Lyons also was "surprised and amazed at the loyalty the graduate students felt to the place."

Kicking off the weekend was a daylong field trip. Everyone got out their "hand lenses and rock hammers," explained Birnie, and two busloads of alumni explored the rock formations in southern New Hampshire. On I-89, they could view a cross-section of major rock units - oldest to youngest and lots of "new exposures, beautiful exposures," said Birnie. It rained, of course, and fairly hard at times, adding yet another nostalgic note for participants who remembered how wet Hanover could be in April.

Birnie gave two major impetuses for the field trip. "First," he said, "when geologists get together we like to go out and see the rocks." Secondly, he explained, "We wanted to bring alumni up to date with the recent advances in New England geology in light of continental drift, which has been an accepted paradigm for only 15 or 20 years, and which revolutionized the field of geology much like Darwin revolutionized other disciplines. Many alumni haven't been back for 15 or 20 years, so they had a new framework in which to look at the rocks."

The weekend continued with a series of lectures by alumni on Friday and Saturday entitled "Linking Earth Sciences and Society." The first session dealt with the earth as a resource, and the second discussed the earth as a dynamic environment. The speakers represented a wide range of fields including oil exploration, mineral and water resources, natural resources law, landuse planning, crisis management, and hazardous waste disposal. Additional talks given by graduates and guests eminent in their fields focused on earth sciences curriculum and research.

According to Birnie, out of these talks came two major emphases: the importance of a general education and the need to develop communication skills. Most alumni praised Dartmouth's wide-ranging education. Jim Vanderbeek '47 asserted that while technical students "start out with a bang" in the job market, hard-working liberal arts students filter their way to the top. "We don't have tunnel vision at Dartmouth, and there was an endorsement by alumni to maintain that. Basic concepts and motivation are a Dartmouth student's specialty, something they'll need out there," said Spydell.

The theme was echoed by keynote speaker Hatten S. Yoder, renowned geologist who currently serves as director of the geophysical lab at the Carnegie Institute in Washington, D.C. He criticized the trend in many of the country's 804 earth sciences departments of changing the name and emphasis of courses centered on basic fields of study, such as geochemistry or stratigraphy, to those concerned more with specific societal issues, such as hazardous waste disposal, flood control, or mineral resources. "This is disturbing to me," said Yoder, "because to understand any of these you have to be familiar with a broad range of disciplines. You must have a strong background in the basic principles because no one can predict what will be the future problems."

Christopher Newhall, Ph.D. '80, a volcanologist and a member of the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) in Vancouver, Wash., also agreed and described how a Dartmouth education helps a geologist in a crisis: "A liberal arts education is crucial in matters of communication to the general public. Also, the field exposure Dartmouth students get through the stretch is helpful in recognizing active geological processes." The stretch, the backbone of the geology major, takes students from Enfield, N.H., to Wyoming to Costa Rica for a term-long period of study. "We immerse them in field work which is the guts of a geology program," asserted Birnie.

Spydell, in a talk on land-use planning and hazards, called for data to be organized in such a manner that it can be communicated to the lay public in a social and scientific manner. Other speakers also stressed communication between geologists and society.

"What's needed most is grey matter to utilize our data. We need leaders who can speak and write, clearly, have broad field research experience, and can work with people," concluded Lincoln Page '31, retired assistant chief geologist with the USGS and "a renaissance man in the geosciences." In his talk on waste disposal, Chuck Ratte, A.M. '55, implored, "We talk about communication, but we're the dullest group going with all our technical jargon. Educate students to talk to people. Go to cocktail parties where there are others besides geologists."

Other points made during the weekend included the decline of the mining industry in this country. Keynote speaker Yoder said this will have an impact on job opportunities for future earth science graduates. In 1976, he said, there were 692 underground mines for non-fuel minerals in the United States; today there are only 405. Similarly, he said, the number of accredited mining schools in the country has dropped from 40 to 19. Yet, ironically, he noted, the United States does not now have an adequate supply of minerals to meet the demands of the economy.

Snow, president of a Denver-based metals exploration company, agreed with Yoder's assessment of the mining business and offered the following as contributing factors: competition from plastics and from Third World countries which sell base metals at much lower prices, and a shift away from an economy rooted firmly in heavy industry to a more service-oriented framework. "McDonald's employs more people today than does this country's entire mining industry," Snow said. "That's how service-oriented we've become. There are a lot of people in this field who are out of work, including those with advanced degrees and experience."

In the field of marine geology, David Duane '56, who works with the National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration, made the point that the oceans offer tremendous possibilities for some of the current problems being tackled by geologists. He said that the large resource in sand off the East Coast could be utilized to help solve the country's current shortage of sand and gravel, and he recommended that the oceans be tapped for waste disposal since only one percent of the water is usable for drinking purposes.

Oceans offer us what we are running out of on land space and resources," he said.

Another conference participant noted that whether in mining or marine geology, most entry-level jobs in the earth sciences today require a degree beyond the bachelor's level. However, industry increasingly is turning to applicants with master's degrees instead of doctorate degrees because they are less expensive to hire and can be trained to meet specific requirements once on the job.

Whenever the talk at the symposium touched on educating students, the focus shifted back to Lyons and Stoiber. "All of us, whatever the respective stages of our careers, feel a sense of gratitude for what Richard Stoiber and John Lyons gave us when we were students in Hanover, and now, for some of us, in on-going professional relationships," said Spydell. Snow expressed the hope that all new faculty members have the "gleam in their eyes" that Stoiber and Lyons have. Page cited an illustration of their superior teaching and training: When a group he was working with needed eight people in a survey, they had to come from Dartmouth. Their supervisor was not going to have time to supervise them, and he asserted that if Dick Stoiber and John Lyons okayed them, they'd be certain to do the job. They did. There is the occasional cynic, like Ratte, who asked "Stoiber, what did you pass me for in Optical Mineralogy? I knew zilch." But even Ratte finally deferred to Stoiber and Lyons, continuing that when he graduated, people were turning to him for answers. In fact, the generations of students educated under Stoiber and Lyons are somewhat humorously known as "The Green Plague" Dartmouth geologists.

"I probably know more about the 'granite in your brain' than most people," said John Lyons, soft-spoken, steely-eyed Frederick Hall Professor of Mineralogy and Geology - a title passed around to the senior active member of the department. Lyons is a "hard rock" geologist who was graduated from Harvard in 1938, then got his M.A. and Ph.D. there in 1939 and 1942, before coming to Dartmouth's faculty in 1946. Since being promoted to full professor in 1953, he has served several terms as department chairman. "I know a bit of everything. I'm more of a generalist," said Lyons. "It takes a long time to get onto the tricks. One has to approach hard rocks from many angles," he noted.

Richard Stoiber, professor emeritus, earned his Ph.D. from MIT in 1936 after getting his undergraduate education at Dartmouth. He joined the College's faculty in 1935 and, after a break during World War II, became a full professor in 1948; he has also served several terms as department chairman. He is best known for his field and laboratory research on volcanic gases, having studied volcanoes all over the world.

He is lesser known as a philosopher, but his thoughtful approach to a discipline usually regarded as technical might qualify him as one. In an article for a book put out by his class on its 50th reunion, he wrote:

"I am neither wholly a teacher nor wholly a research scholar. I am a scholar-teacher. University-level teaching should demand both. Dartmouth has for years referred to its teacher-scholars. I suggest we need the scholar first, hence the inversion of the Dartmouth phrase. You probably remember your teachers. Scholars, on the other hand, were perhaps a bit forbidding, but think back. I suspect you really admired your scholarly university teachers whose subjects excited you. Again we are back to the thought that to excite students is what it's all about."

Also, while discussing the thrill of the scientist stepping "where the foot of man had never trod," he writes, "It is not how long you stayed at the forefront, but that by your careful work and intuition you were there." Along these same lines are his conclusions on the symposium: "The fact that all these people came was the biggest, most important thing. The sheer bulk of them doing it amazed me."

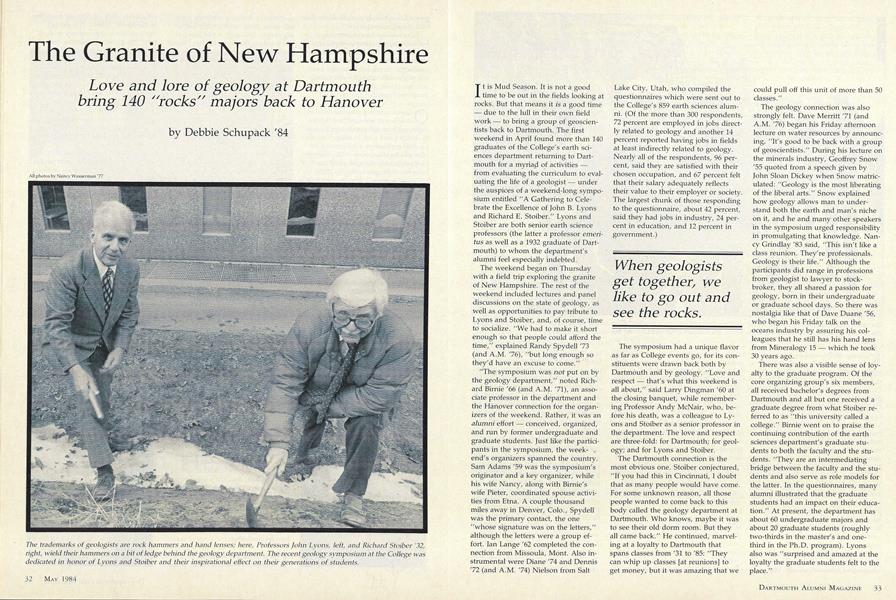

The trademarks of geologists are rock hammers and hand lenses; here, Professors John Lyons; left, and Richard Stoiber '32,right, wield their hammers on a bit of ledge behind the geology department. The recent geology symposium at the College wasdedicated in honor of Lyons and Stoiber and their inspirational effect on their generations of students.

The rock ledges exposed by the relatively recent roadcuts for the interstate highways are a geologist's paradise. Here, a group ofthe field trip participants walks along the berm, thoroughly engrossed by the tale told in the rocks.

The close-up view through his hand-lens intrigued this rock hound, despite the rain. One of the two buses used to carry the reunioning geologists on their field trip to southern New Hampshire is parked on the shoulder of the highway, in thebackground. The field trip was followed by a series of lectures by alumni beginning with a talk on the earth as a resource, andcontinuing with a session on the earth as a dynamic environment.

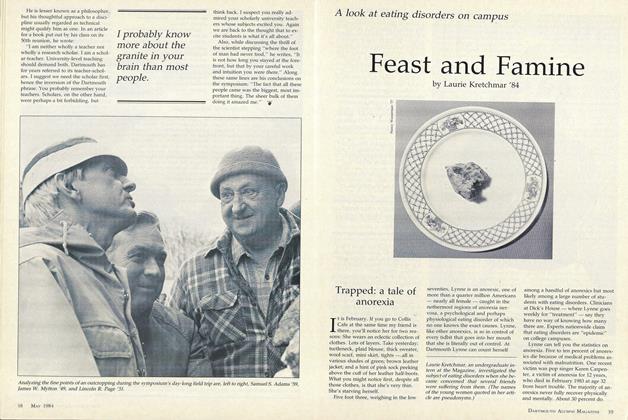

Analyzing the fine points of an outcropping during the symposium's day-long field trip are, left to right, Samuel S. Adams '59,James W. Mytton '49, and Lincoln R. Page '31.

When geologistsget together, welike to go out andsee the rocks.

A Dartmouth education helps a geologist in crisis.

I probably knowmore about thegranite in yourbrain than mostpeople.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureFeast and Famine

May 1984 By Laurie Kretchmar '84 -

Feature

Feature"The Highest-Ranking Woman in American History"

May 1984 By Shelby Grantham -

Cover Story

Cover StoryA Return to Dartmouth

May 1984 By Brian W. Ford '67 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1959

May 1984 By William G. Long -

Class Notes

Class Notes1956

May 1984 By Clement B. Malin -

Class Notes

Class Notes1979

May 1984 By Burr Gray

Debbie Schupack '84

-

Article

ArticleFreshman Book to Aegis

November 1983 By Debbie Schupack '84 -

Article

ArticleWhy "Why Not?"

JANUARY/FEBRUARY 1984 By Debbie Schupack '84 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryA New in the Neighborhood

MARCH 1984 By Debbie Schupack '84 -

Article

ArticleIt's Just Like Talking to People

APRIL 1984 By Debbie Schupack '84 -

Article

ArticleGetting Ahead on the Mommytrack

OCTOBER 1990 By Debbie Schupack '84

Features

-

Feature

FeatureTurkeys for Dartmouth

April 1955 -

Feature

FeatureWho will pay—and how?

April 1962 -

Feature

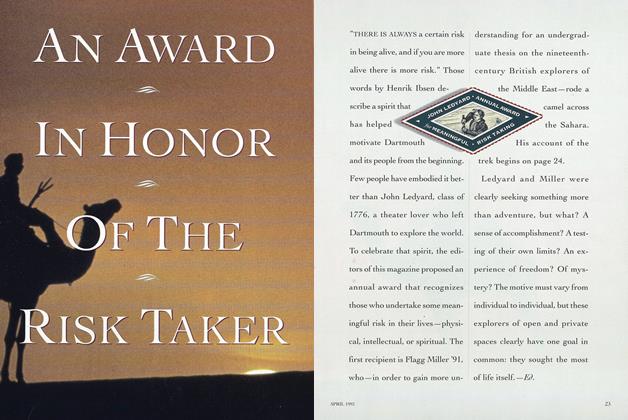

FeatureAn Award In Honor Of The Risk Taker

APRIL 1992 -

Feature

FeatureThe Diminishing Citizen

July 1962 By BASIL O'CONNOR '12 -

Feature

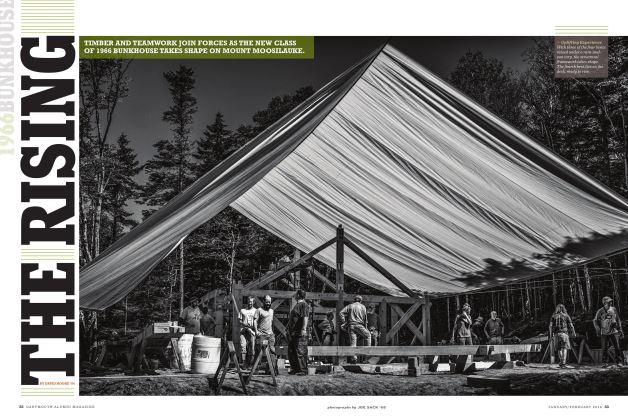

FeatureThe Rising

JANUARY | FEBRUARY 2016 By DAVID HOOKE ’84 -

Feature

FeatureThe Ultimate Guide

Jan/Feb 2013 By MARGARET WHEELER AS TOLD TO JIM COLLINS '84