THE VOYAGE IN: FICTIONS OFFEMALE DEVELOPMENT

Edited by Elizabeth Abel,Marianne Hirsch,and Elizabeth LanglandThe University Pressof New England, 1983. 366 pp.,$25.00 cloth, $11.95 paperback.

Before 1970, candidates for the Ph.D. in literature had but one standard, and it was male drawn by male professors from male authors writing for the most part about male protagonists. Those of us who were women studied men, long and hard. We discussed their plights, ferreted out their meanings, and articulated their aesthetics; we studied their biographies, pieced together their symbolisms, and worried their psychoses into theories. Putting aside our own experience, we listened carefully to our male colleagues (not only did they know first-hand what it was like to be male, but they were also more numerous, much louder, and more certain than we).

The women scattered thinly through the curriculum were by comparison depressing and dull. Their lives were limited and their fates usually tragic. We dismissed them as failed men. Then we made the ugly discovery that our tickets to academe were good only to the assistant professor level and that we ourselves faced limitation and failure. We began to wonder whether there might be more in those "secondrate" works than we had thought. At the very least, there might be lessons in survival there. But we had no vocabulary with which to investigate them, no categories within which to organize them, no critical traditions or historical frameworks to fit them into. Nor was there much collegial or institutional support for taking them seriously. To concern oneself with women authors or characters too deeply was to "trivialize" one's career, to lose dissertation fellowships, to alienate mentors, to risk unemployment.

With the backing of a widespread movement of women to take themselves seriously, however, that changed. One by one, supporting each other in the risky venture, women in academe dared to study women, and out of that daring, inch by inch, have developed the solid beginnings of a critical tradition equipped to explore literature from a female as well as a male perspective.

This collection of essays, one of each of 16 professors, three of them from Dartmouth, is a valuable peg in the construction of that tradition. Editors Abel, Hirsch (who is in the Dartmouth French and Italian department), and Langland have gathered here a rich sample of modern gender-conscious criticism. It explores one traditional literary genre the Bildungsroman ("novel of education"). Taking as texts a wide range of nineteenth- and twentieth-century fiction by and about women, the essayists point out the maleness of the traditional Bildungsroman,. which concerns itself with a young man's adventures in society while, like an ever-correcting compass, he moves from ignorance and inno- cence to wisdom and maturity. The genre, thus defined, makes no sense for a woman protagonist, for whom, as Hirsch explains, "social options are often so narrow that they preclude exploration of her milieu." Therefore, argue these critics, the kind of development women in literature have done and may do must be seriously explored in the light of the social and psychological constraints and skills peculiar to womanhood. Their conclusion, upon doing so, is that woman's Bildungsroman is usually an inward rather than an outward adventure.

Most of the essays are pitched to- ward the traditional scholar, but some describe so enticingly recent writing and thinking by and about women that even the general reader must be caught up in the thrill of discovering this new lode. My spirit was lifted measurably, for instance, by the reprint of a 1979 essay written by Blanche Gelfant (one of Dartmouth's first tenured women). Discussing the death of Molly Fawcett, protagonist of Jean Stafford's novel TheMountain Lion (1947), Gelfant points out that she "had dreamt of becoming a poet, but she lacked not only a type- writer (for which she wrote letters of solicitation comic to us and futile to her); she lacked a sense of the reality of this possibility, examples for a way of life she could barely imagine, let alone live. She belonged like the mountain lion to an endangered species, for which at the time there were no plans for preservation." Gelfant's conclusion is stirring: "Today we can imagine what thirty-five years ago Jean Stafford could not a future for Molly. That future requires another literary form, one in process of being shaped. I mean the novel that will present a portrait of the artist as a young woman, a novel of initiation that will describe female rites of passage."

Ellen Rose's essay examining con- temporary revisions of fairy tales spoke to me not only-as a woman but as a parent. She discusses the vibrant reworkings of such tales as Cinderella, Snow White, Rapunzel, Little Red Rid- ing Hood, Bluebeard, and Beauty and the Beast by Anne Sexton, Olga Brou- mas, and Angela Carter. They are wit- ty and wise new stories in which mothers, not brothers, rescue their daughters from murderous husbands; in which little girls confront, embrace, and learn to live happily with wolves and lions; and in which it is discovered that mirrors are "invisible cages." There are faith, hope, and charity in Rose's conclusion: "What can fairy tales, retold by women, tell us about female development? That it has been distorted by patriarchy; that it is and must be grounded in the motherdaughter matrix; that it involves not only the discovery but the glad acceptance of our sexuality. That a woman who loves the woman who is herself has the power of loving another person. And perhaps someday even patriarchy will 'yield' to that power."

All this is heady stuff; but perhaps the greatest single value of this thick volume is the charting it does for us of the world of contemporary fiction by women (conveniently codified in a 102item appendix of works cited). I came away from it anxious to read familiar novels in new ways, and to buy new novels that have incredible to imagine credibly happy endings. A great gift in a world altogether too besotted with bleakness.

Shelby Grantham has been a memberof the editorial staff of the AlumniMagazine since 1976; her doctorate isin English literature.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

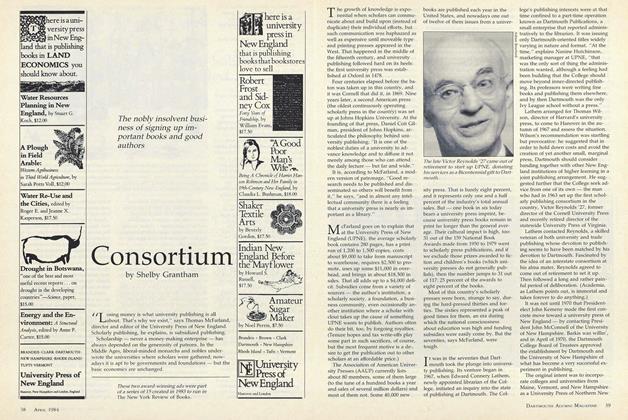

Cover StoryConsortium

April 1984 By Shelby Grantham -

Feature

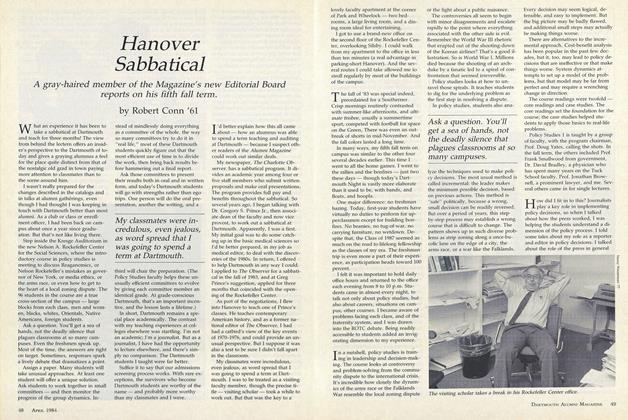

FeatureHanover Sabbatical

April 1984 By Robert Conn '61 -

Feature

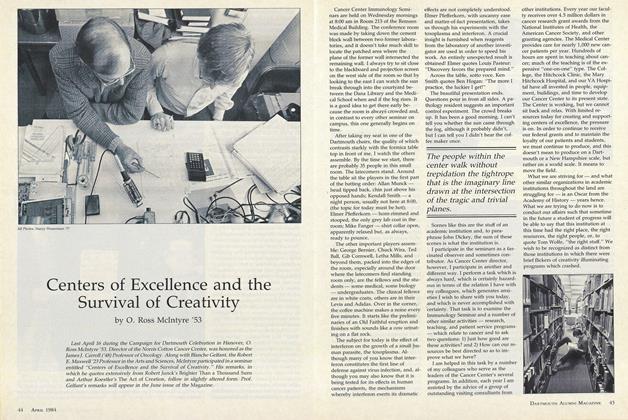

FeatureCenters of Excellence and the Survival of Creativity

April 1984 By O. Ross Mclntyre '53 -

Feature

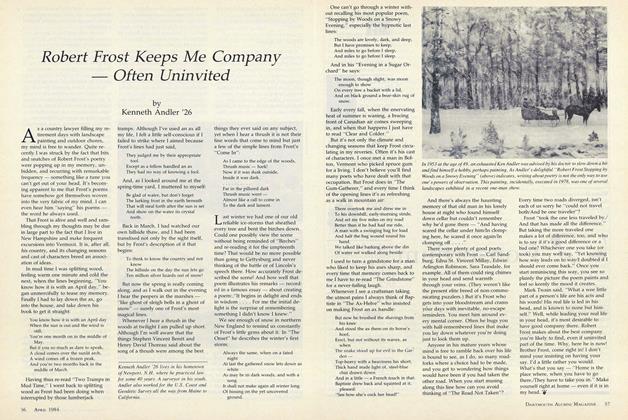

FeatureRobert Frost Keeps Me Company Often Uninvited

April 1984 By Kenneth Andler '26 -

Article

ArticleIt's Just Like Talking to People

April 1984 By Debbie Schupack '84 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1959

April 1984 By William G. Long

Books

-

Books

BooksCemetery

JUNE 1932 By Albert William Levi, Jr. -

Books

BooksDartmouth Authors

OCTOBER 1985 By Mark Woodward '72 -

Books

BooksThe American People and Nation.

APRIL 1928 By Philip A. Cowen -

Books

BooksRICHARD EBERHART: SELECTED POEMS 1930-1965.

DECEMBER 1965 By ROBERTS W. FRENCH '56 -

Books

BooksTHE STRUCTURES OF THE ELEMENTS.

December 1974 By ROGER H. SODERBERG -

Books

BooksGREEN MEMORIES,

January 1948 By STEARNS MORSE.