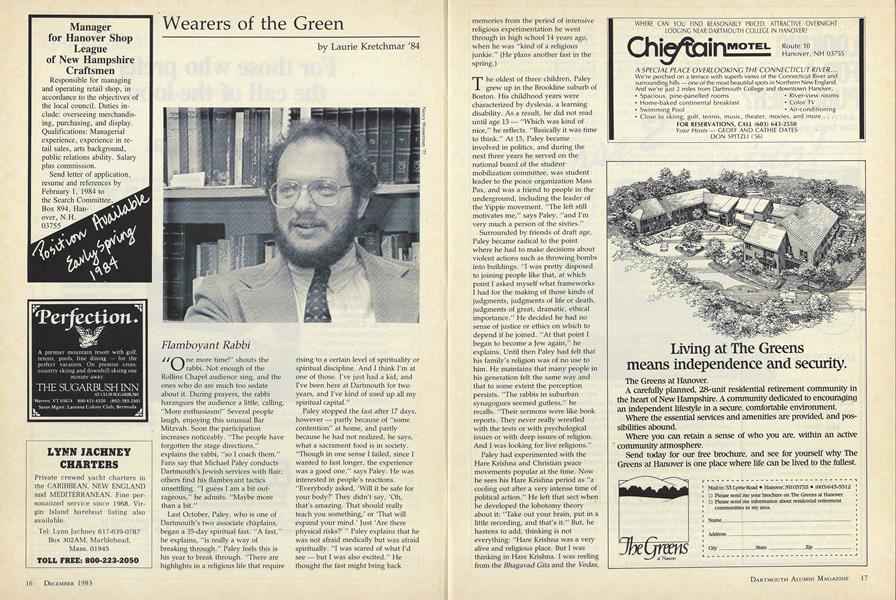

"One more time!" shouts the rabbi. Not enough of the Rollins Chapel audience sing, and the ones who do are much too sedate about it. During prayers, the rabbi harangues the audience a little, calling, "More enthusiasm!" Several people laugh, enjoying this unusual Bar Mitzvah. Soon the participation increases noticeably. "The people have forgotten the stage directions," explains the rabbi, "so I coach them." Fans say that Michael Paley conducts Dartmouth's Jewish services with flair; others find his flamboyant tactics unsettling. "I guess I am a bit outrageous," he admits. "Maybe more than a bit."

Last October, Paley, who is one of Dartmouth's two associate chaplains, began a 35-day spiritual fast. "A fast," he explains, "is really a way of breaking through." Paley feels this is his year to break through. "There are highlights in a religious life that require rising to a certain level of spirituality or spiritual discipline. And I think I'm at one of those. I've just had a kid, and I've been here at Dartmouth for two years, and I've kind of used up all my spiritual capital."

Paley stopped the fast after 17 days, however partly because of "some contention" at home, and partly because he had not realized, he says, what a sacrament food is in society. "Though in one sense I failed, since I wanted to fast longer, the experience was a good one," says Paley. He was interested in people's reactions. "Everybody asked, 'Will it be safe for your body?' They didn't say, 'Oh, that's amazing. That should really teach you something,' or 'That will expand your mind.' Just 'Are there physical risks?' " Paley explains that he was not afraid medically but was afraid spiritually. "I was scared of what I'd see but I was also excited." He thought the fast might bring back memories from the period of intensive religious experimentation he went through in high school 14 years ago, when he was "kind of a religious junkie." (He plans another fast in the spring.)

The oldest of three children, Paley grew up in the Brookline suburb of Boston. His childhood years were characterized by dyslexia, a learning disability. As a result, he did not read until age 13 "Which was kind of nice," he reflects. "Basically it was time to think." At 15, Paley became involved in politics, and during the next three years he served on the national board of the student mobilization committee, was student leader to the peace organization Mass Pax, and was a friend to people in the underground, including the leader of the Yippie movement. "The left still motivates me," says Paley, "and I'm very much a person of the sixties."

Surrounded by friends of draft age, Paley became radical to the point where he had to make decisions about violent actions such as throwing bombs into buildings. "I was pretty disposed to joining people like that, at which point I asked myself what frameworks I had for the making of those kinds of judgments, judgments of life or death, judgments of great, dramatic, ethical importance." He decided he had no sense of justice or ethics on which to depend if he joined. "At that point I began to become a Jew again," he explains. Until then Paley had felt that his family's religion was of no use to him. He maintains that many people in his generation felt the same way and that to some extent the perception persists. "The rabbis in suburban synagogues seemed gutless," he recalls. "Their sermons were like book reports. They never really wrestled with the texts or with psychological issues or with deep issues of religion. And I was looking for live religions."

Paley had experimented with the Hare Krishna and Christian peace movements popular at the time. Now he sees his Hare Krishna period as "a cooling out after a very intense time of political action." He left that sect when he developed the lobotomy theory about it: "Take out your brain, put in a little recording, and that's it." But, he hastens to add, thinking is not everything: "Hare Krishna was a very alive and religious place. But I was thinking in Hare Krishna. I was reeling from the Bhagavad Gita and the Vedas, and I would say to people, 'Do you see what this says?' and they would say, 'Stop reading. Start chanting,' and I'd say, 'I'll chant later.' "

Paley went to a draft demonstration where Orthodox Jews were "davvening" praying in front of draft buses.

"I said, 'These are people I have to meet' because until then I had written Judaism off as a very dead religion." Eventually, Paley went to live with his new-found friends at an alternative rabbinical seminary in Somerville, Massachusetts.

A telling moment came for Paley at another demonstration, this one in front of the State Department in Washington: "I watched all of us get sprayed with pepper gas, and I watched all these other people wearing suits and carrying attache cases walk into the State Department through the front door. That's the time I said, 'These guys are having a greater impact on the State Department than I am, and these guys aren't getting gassed.' That disparity was a big issue for me."

After that, Paley knew he wanted a "ticket" to political power. He would become a rabbi and merge his political interest with his love of spirituality. His decision to live and work at Dartmouth came not much later. As a freshman studying at Brandeis, Paley visited Dartmouth in 1970, two years before the College's first rabbi was appointed. When Paley visited, services for Dartmouth's Jewish students were held only occasionally, led by one of the religion professors or a counselor. Paley conceived a dream: "I wanted to come to Dartmouth to be the Hillel rabbi." It took him ten years.

Paley selected Dartmouth because it fit all of his specifications. "Dartmouth was certainly a place of power. Also, I wanted a kind of subsistence, rural, intellectual New England small group and intensely religious experience. I had a vision," he says with a smile, "of being a rabbi in the morning and teaching classes in the afternoon and farming in the late afternoon and skiing all winter long and that's what I do, except the farming." Orthodox Jews do not drive on the Sabbath, so Paley lives within walking distance of the campus. Also, he is busier than he originally expected.

Paley is rabbi to more than 300 Dartmouth Jewish students and approximately 180 Jewish families of the Upper Valley. An experienced teacher who was once chosen

"Professor of the Year" at Temple University, he leads Hebrew, Talmud, and Buber study groups. He sits on several College committees, including the Committee on Undergraduate Life. And he gives his energetic weekly services, where he sometimes tells jokes "Which I'm roundly criticized for, I understand."

Paley's main concern at Dartmouth is improving student life. "To be a Jew at Dartmouth is a more complicated thing than to be a Jew at most other campuses," he says. Dartmouth's Jewish population, he figures, is about 10 percent of the student body 12 percent lower than at any other Ivy League institution. Furthermore, Paley estimates that fewer Jewish students matriculated in the Class of '87 than in the previous two years. He's worried about that. He is also concerned about the lack of a strong Jewish identity on campus. "I've never been at a place where I've had so many conversations

— I mean 60 or 70 with students who are debating whether they ought to tell other students they're Jewish. That's just unheard of anywhere else." Paley links both problems to an environment that in the past has been unsupportive. It can change, though, he says, and is changing.

"I think the Dartmouth Jewish community both on campus and off

has to change. It has to become more proud of who it is and more conscious of what it can offer." Paley has plans to hold events such as a concert of Jewish composers, a colloquium on Jewish physics ("so that Jews can see some of their legacy in that intellectual pursuit"), and a Jewish arts and crafts festival.

Paley also has some ideas for the curriculum. "You can't take Hebrew here," he explains. "This College has one of the most renowned language reputations in the world. It's outrageous that you can't take Hebrew here and that it's 1983 and I'm still working on it. There's a sizeable population of students here who want to take Hebrew." Nor does Dartmouth offer a foreign study program anywhere in the Middle East, although each year about five students go to Israel on their own. "I think that people look at Dartmouth and say to themselves, 'Small percentage of Jews, no Hebrew taught, no consistent Judaica program, and a rural area where there's no great community of Jewish support. So why come here?' "

Yet, Paley thinks, the actual situation

is better than most people outside of Dartmouth realize. "One of our biggest problems is to get the impression of the College to catch up with the facts. A lot of Jewish alumni feel that the Jewish aspect of their Dartmouth experience here was ambivalent, while their general experience here was excellent. It's important to get the message out that it can be good to be Jewish at Dartmouth. Alumni must explain that to guidance counselors and rabbis and friends. It's a slow process."

Looking out the window of his Tucker Foundation office Paley catches sight of the bonfire under construction by the Class of '87 and he laughs. "I see myself as a sort of arsonist, building little Jewish bonfires through books and prayer and music and art." To reintroduce the sacred into the modern world is no easy task, according to Paley. "It is really my hope to do that," he says. "I lead energetic services because I don't think you can do it alone. I think you need to ride on a crest of energy." And that he is why he wants his 20- to 30- member weekly audience to participate actively during services.

Paley disagrees with students who argue that religion is a sedate and private affair. He points out that his services get far higher attendance than those of the previous, more formal rabbi did and laments the decline of once-vibrant Jewish services: "On High Holy Days in Rollins Chapel you might get one-fifth of the people remotely involved in a prayer, but no one's moving. You don't see anybody really enthusiastic about the prayer. We're not brought up that way. People say this is supposed to be solemn and dead." Paley doesn't think so. "You can't find one place in the Torah that says, 'Sing solemnly to the Lord.' It's always, 'Sing joyously to the Lord.' You don't find, 'And the trees were silent and depressed and therefore they praised the Lord.' It's always, 'God made the oak trees dance and stripped the forest bare, and the light of God rang out as strong as the roaring water!' "

Laurie Kretchmar, a Californian, is oneof this year's Whitney Campbell undergraduate interns at the Magazine.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeaturePsycho-Social Dynamics and the Prospects for Mankind

December 1983 By Charles E. Osgood '39 -

Feature

FeatureMaris Bryant Pierce: A Seneca Chief at Dartmouth

December 1983 By Howard A. Vernon -

Cover Story

Cover StoryCROSSROADS

December 1983 By Shelby Grantham -

Feature

FeatureOn a Scale of 1 to 10...

December 1983 By Brad Hills '65 -

Feature

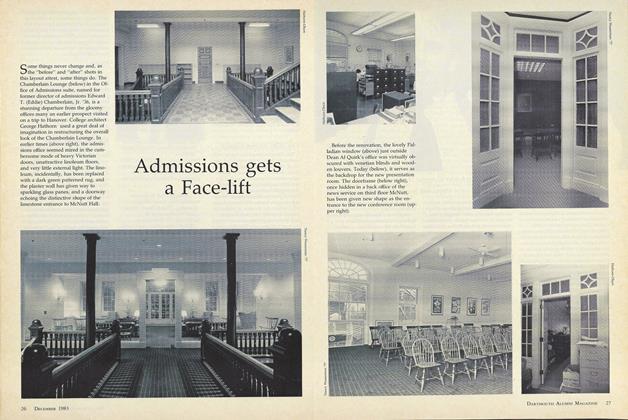

FeatureAdmissions gets a Face-lift

December 1983 By Nancy Wasserman -

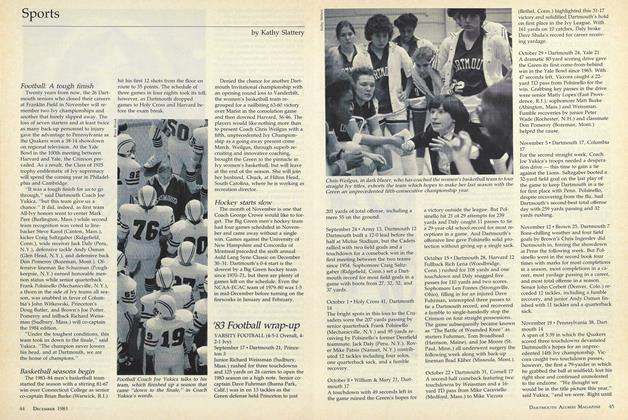

Sports

SportsSports

December 1983 By Kathy Slattery

Laurie Kretchmar '84

-

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLetters

MAY • 1988 -

Article

ArticleThe Dartmouth Intern: Spying on the Real World

OCTOBER, 1908 By Laurie Kretchmar '84 -

Article

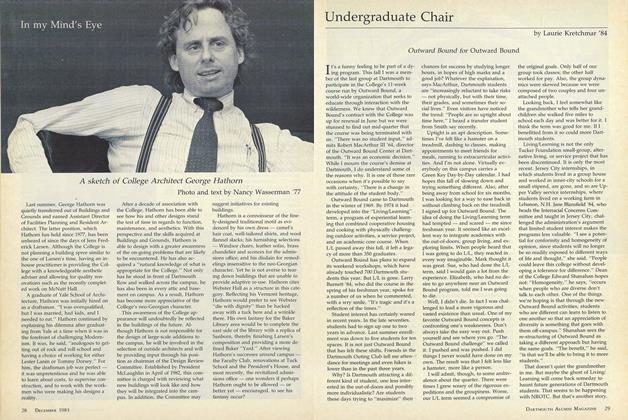

ArticleOutward Bound for Outward Bound

DECEMBER 1983 By Laurie Kretchmar '84 -

Article

ArticleAudacious Questions

MAY 1984 By Laurie Kretchmar '84 -

Feature

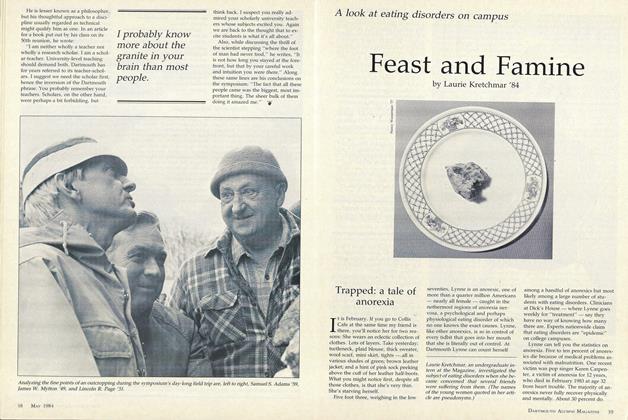

FeatureFeast and Famine

MAY 1984 By Laurie Kretchmar '84 -

Article

ArticleThe Absolute and the Ambiguous

JUNE/JULY 1984 By Laurie Kretchmar '84