"We wanted to drop a bombshell of internationalism on the Dartmouth campus," said Geoff Berlin '84, a math and social sciences major, explaining how nine student organizations under his coordination joined together to form the Global Outreach Committee and present an International Week in early May. There were panel discussions on international careers, work abroad, and the role of the Third World in international relations, with speakers like Dennis C. Goodman '60, with the U.S. mission to the United Nations, and Facouq Sobhan, U.N. ambassador from Bangladesh, going to fraternities and sororities to discuss international relations and careers in the field. There were distinguished addresses given by Professor John Rassias, Nobel Laureate and visiting Montgomery Fellow Czeslaw Milosz, and, in closing, Dr. Zbigniew Brzezinski, national security advisor in the Carter Administration and professor of government at Columbia University.

Brzezinski described a one-dimensional Soviet Union and a polarized United States in a speech on dilemmas of U.S. foreign policy before a large crowd in Spaulding Auditorium. Brzezinski first outlined two important trends currently intersecting in Soviet foreign policy: a significant retrenchment in Soviet globalization along with a concentration on Western Europe and the Middle East, and a re-focusing of Soviet policy from the Atlantic to the Pacific. He said the Soviet Union is "trying to preserve power with the United States" and possibly seek attainment of a. strategic edge in order to use political intimidation. Brzezinski said the Russians have also adjusted their position ideologically: "Rather than associating with the Third World, they are now capitalizing on the peace movement in West Europe." He later stated that the Soviet Union has outlived its role as a revolutionary model and is now a one-dimensional power without ideological, cultural, or economic appeal, only military force. "In my opinion that poses the problem not of Soviet domination but of global chaos," he said.

When the Russians suspended arms control talks, they were not suspending negotiations, Brzezinski pointed out, noting that suspension of talks is itself a form of negotiating. In this context came the withdrawal from the Olympics. "To be sure, there is an element of political revenge," he said, a response to the U.S. refusal to attend the 1980 Summer Olympics in Moscow. "But," he added, "if the Soviet U.S. relationship had been unfolding satisfactorily from the Soviet point of view, particularly on some of the nuclear issues, you can be absolutely sure the Soviet Union would have participated."

The Soviet strategy of concentrating to the west and south coincides with American strategic interests in Western Europe, the Pacific, and the Persian Gulf, he said. He described Western Europe in a vague trend of "historical fatigue" produced by two world wars and characterized by a "culture of hedonism, sense of purposelessness, and inability to assume a larger, energetic world role."

"Such a Europe faces a real danger," Brzezinski said, "of becoming dependent for its own markets on the Soviet Union and thus in effect producing a shift in Western power which has been so carefully maintained since World War II."

With an American policy that has changed every four years with each new administration, he said the urgent task of the next president is to rebuild a consensus of foreign policy through a "deliberate" pursuit of bipartisanship. Brzezinski suggested appointing members of the opposite party to key positions in government. Brzezinski suggested that if the Democrats gain the presidency they should consider for secretary of state Republican Senators Mathias of Maryland or Baker of Tennessee. Brzezinski concluded by saying the future will be shaped "not ... so much by our adversaries but on how we conduct our foreign policy." He noted that Americans tend to think of conflict with the word "resolution." But, he said, "conflicts do not get resolved . . . they must be managed, mastered, engaged in on a never-ending basis."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureProfessor John Stearns '16: Rara Avis Una

June | July 1984 By Eddie Chamberlain '36 -

Feature

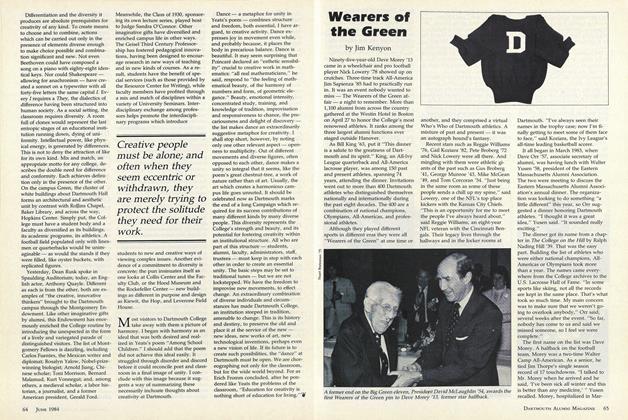

FeatureCreativity: The Open Dance at Dartmouth

June | July 1984 By Prof. Blanche Gelfant -

Feature

FeatureWearers of the Green

June | July 1984 By Jim Kenyon -

Feature

FeatureThe Best Part of My Academic Life Here

June | July 1984 -

Feature

FeatureMaking it Happen

June | July 1984 By Peggy Sadler -

Feature

FeatureThe Quiet Good Man

June | July 1984 By Young Dawkins '72

Article

-

Article

ArticlePROFESSOR A. N. WHITEHEAD DELIVERS MOORE LECTURES

JANUARY, 1927 -

Article

ArticleAlumni Council Nominees, District 1

May 1947 -

Article

ArticleMarch Glee Club Tour

MARCH 1969 -

Article

ArticleTRACK

JUNE 1970 By JACK DEGANGE -

Article

ArticleProfessor Faith Dunne:

April 1993 By Karen Endicott -

Article

ArticleThayer School

June 1953 By William P. Wimball '29