Teaching English in the People's Republic of China

[The following is excerpted from a speech given at the Dartmouth Hub Club in Boston by Professor Sears, amember of the College's Department of English. Dr. Sears taught American literature and English compositionlast year at the Guangzhou Foreign Language Institute in the People's Republic of China. Ed.]

Ursula, a Junoesque colleague of mine at the Guangzhou Foreign Language Institute, scandalized the Chinese with her gold-flecked eyeshadow and her black lace unmentionables - still unmentionable in China which she flew like banners from the bamboo drying poles above her balcony.

Ursula wrote anecdotes about her teaching experience for German newspapers. She used to tell me that if you stayed in China for three weeks, you'd write a book, and if you were there for three months you'd turn out an article, but if you stayed for a year, you wouldn't write anything. She was right. The truths are too complex, too hidden, too deep for my made-in-the- USA shovel.

I'm not a Sinologist, nor did I go to China to study it, nor can I tell you "the truth" about it. I went to teach American literature and advanced composition to students who thought Jack London was inspiring the masses to revolution in America, and that Americans charged their aged parents for dinner. I also went to the woods of the third world like many another American to "front only the essential facts of life, and see if I could not learn what it had to teach."

Dartmouth has about 4,000 accomplished undergraduates, male and female, whose annual college costs amount to more than $15,000. Guangzhou Foreign Language Institute has about 1,000 accomplished undergraduates, male and female, whose annual college costs amount to about $80. Baker has 1.5 million volumes; the Guangzhou library might have as many as 15,000. I counted 26 sports listed in the Dartmouth General Information Bulletin; at Guangzhou, teachers, staff, students, and anybody else from the political unit who wanted to join in played tug-of-war, soccer, basketball, badminton, track, and ping pong.

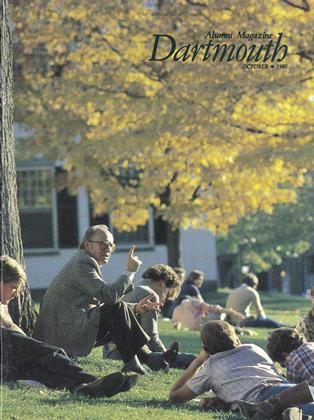

I could also describe some snapshots of the two institutions: the familiar shot of a student walking across the Green at night looking up to the Baker beacon and beyond to the stars; or of seniors together marching across the Green on graduation day, too-soon nostalgic. Or show you the Guangzhou Institute at 7:00 a.m., when the students saunter along the dirt pathways between the hibiscus bushes, reciting, "Hello. How are you? Nice to see you again," or reading aloud "Annabelle Lee" or the Gettysburg Address as they sidestepped the free chickens. Or hurry to the basketball court at dusk on Saturday nights for the free weekly movie, carrying their wooden, straight-backed chairs and the übiquitous black umbrellas. Or stumble toward the soccer field at 6:00 a.m. for calisthenics while the loudspeakers crackle "The East Is Red" or "Que Sera Sera" by Doris Day.

But I can't tell you "the truth" about China. All I can tell you is something of the life sensation, as Conrad says, of being a Dartmouth professor teaching American literature and writing to Chinese students in the People's Republic. I do that best by telling several stories, since stories are as close as we come to "the essential facts of life."

On August 27, 1983, I was greeted at the airport by a committee from the Guangzhou Foreign Language Institute headed by the dignified and deaf Shakespearean professor Gu, a friend of a Dartmouth student's father. We bowed, "Ni hou'ed," and "joined our hands in shaking."

Professor Gu and a party official escorted me to the chauffeured car, which looked like a cross between a '56 Plymouth and a New York taxi with lace curtains at the windows and a feather duster on the back shelf. I intoned in Chinese the speech I had prepared with Professor Susan Blader before leaving Dartmouth about how across the four oceans men are brothers and how honored and delighted I was to be there, etc. They laughed. I think they thought I'd done it for a laugh.

My first impression of the other side of the world was utter otherness. Nothing was familiar. Not the eucalyptus and bamboo trees on the 800- foot White Cloud Mountains behind the Institute; not the dry, cracked sienna soil like shards of ancient pottery; not the soldiers wearing khaki sneakers and Oversized, wrinkled uniforms as they bent in the fields wrapping chrysanthemum heads in cellophane for Hong Kong markets. Not the smell of the nightsoil the peasants were dumping by the bucketful onto bean fields and rice paddies surrounding the Russian-built, rabbit-hutch apartments where the Institute foreigners lived. Not the saucer-sized spiders in my bedroom, nor the stone slab which tilted toward a black hole in the floor that was my sink.

The students too were other at first. Upside down. I couldn't pronounce the names correctly, so I called them by the English names they'd been assigned by a British literateur: Horatio, Araminter, Wellington, Bertram, Deacon. I was vexed, despite my resolution to be exemplary, by their formality, solemnity, and passivity: only their watchful eyes moved. They seemed pre-Freudian to me, pre-Maslowian, pre-lapsarian even. They referred to themselves as "boys" and "girls," even though most were in their early twenties. They began conversations with apologies for inexperience and immaturity, conversations that continued, after we came to trust each other, onto subjects such as where babies came from; who Freud was; whether Buddhism was a real religion; why Westerners considered sex so important. Most acted as though altruism, concern for family and friends, integrity, and devotion to others were both real and normal, not merely a means of serving the individual's best interests. In general they defended the no-dating, no-dancing, no-falling-in-love policies of the Institute as necessary. Otherwise, they'd be distracted from their primary objective - realizing the Motherland's Four Modernizations Program in industry, agriculture, national defense, and science and technology. I felt, as Saul Bellow says, "in the suburbs of reality."

After a month or so, the students began to come to my apartment across from the police station, despite the official discouragement, amounting sometimes to prohibition, of associating with the contaminated foreigners, who were characterized in the press as "germs spreading an ideology infested with decadent bourgeois ideas and styles of life."

Deacon had been assigned to my writing course and later audited my American literature course, which included selections from the Old and New Testaments. He brought me some of his treasures a little sesame seed oil and a bag of dried peas. He asked if he could do anything for me: interpret, translate my book into Chinese, perhaps, scrub my floor. He apologized for being so presumptuous as to come to my house and to bring me presents. He said that he had come to consult his "dear teacher in his rough way," if it were not inconvenient, about religion.

He wanted to know if all Americans were religious and how they could believe in science and God at the same time. I explained about different ways of knowing and about science as an answer to the question "how" and religion as an answer to the question "why." Deacon nodded vigorously, but I don't think he understood. The next day I discovered that the peas were infested with bugs; however I felt that Deacon had anointed me with the oil.

Our conversations continued, although seldom in the classroom. (My Chinese students had been trained to listen and to record and to memorize two-hour lectures verbatim. The first question on the national literature examination is: "Write the longest passage you have ever memorized from American literature." They were not encouraged to comment, criticize, or question.) Deacon described Americans as energetic and hard-working and introduced me to the two most prevalent misconceptions about the U.S. Why, he asked, do Americans charge their parents when they come to dinner, and why do we send our cats and dogs to pet hotels? We talked about the decadence of disco dancing; the puzzle of why God created mosquitoes to plague us, the very image of Himself; Marx's debt to Hegel; the "loving funny" (fun-lovingness) of Dartmouth students - which confounded Deacon. He had 26 to 28 hours of class a week, and he studied in an open 8' x 15' room with five other students and a host of tropical insects. Or in a small library, also without screens and without heat in January and February, when the temperature was in the thirties and forties. The library had one reading room for 300 students, many of whom lined up outside before it opened in order to get a seat under one of the 6-foot unshaded fluorescent lights hanging from the ceiling.

I showed Deacon pictures of the Dartmouth campus and the countryside. He said it looked like Heaven, and he sometimes dreamed of being admitted. He was astonished that students were allowed to dance and to marry. If the authorities in China discovered that a student had a "friend," his or her life-long job assignment given after graduation might be to live in cold Xinjiang near the Russian border and translate directions for assembling bicycle parts. The regulations were practical. If you fell in love before graduation, your unit wouldn't give you permission to marry, and upon graduation you might be sent to Tibet and your friend to Beijing. Forever. And since the low wages (about 60 yuan, or thirty dollars, a month) preclude travel, it was best to sublimate your energies into realizing the Motherland's Four Modernizations.

Deacon didn't buy it, as he confessed to me after we had been talking for five or six months. First, he was a very emotional man, which I found to be typical of the Chinese. (Whenever he spoke, whether the subject was puritanical repression or the Italian songs that he had learned before he became a student, he spoke so operatically that the little lizards, known as "wall tigers," would run for the corners.) Secondly, Deacon objected because he was in love with a former classmate now studying in Szechwan. In the journal he kept for American litera- ture, he copied one of his "sugar re- ports" to his sweetheart. (I asked Deacon if I could make a copy of his journal, since I was collecting material for an anthology of Chinese students' prose. He agreed. I have the only copy now, since the journal was later stolen. As a precaution, I had had a British colleague take my copy to Hong Kong to send home because my mail was being read, and some letters had been destroyed or censored.)

Deacon's "friend" had written to him first and enclosed a picture of herself standing before Heaven's Pool in the snowy mountains of Szechwan. She said she loved the "green" of Guangzhou and hoped "the people" there would also love the "white snow" of Szechwan and hoped that he would post her a "green leaf." Deacon said he fell before the picture and added that "even a complete fool" could understand what was meant. At that point he resolved to cherish her friendship - "pure friendship, not beyond, because I feel abased: I am small; she is tall. I am a mortal; she is an angel. I am a clay pot; she is a jade statue."

Deacon was uncertain about the letter and consulted the political monitor of the class, a student responsible for herding his peers along the ideological straight-and-narrow, as well as solving practical problems such as taking notes for absentees and securing hospital beds for those with hepatitis, which was common at the Institute. Holmes, the monitor, confirmed it was a love letter, and admonished Deacon not to worry that she was beautiful while he was not, because it didn't matter: "Man for ability, women for beauty."

Deacon answered the letter to ask if her meaning "kissed" his. He said he was intoxicated by her letter but tried to be as calm as the water in Heaven's Pool, since he must not be diverted from the realization of his ideals. Yet, he said, "It seems that I can feel the beating of your pulse, and feel that your face is covered with a transparent silk, but can be seen clearly. It is I that should take it off." He said he knew what she meant about the leaf. "If it were a mere green leaf you asked for, your wish is not so difficult to satisfy. But I am not so simple as to take the leaf you ask for to be the leaf of a tree. I needn't, now, pretend to be a fool. . . . Chen, the snow in the West is pure, and the green leaf in the South is tempting." He concludes, "Have you ever thought of a jade girl statue? If I can have it, I'll be the happiest; if not, I would't be so regretful. For I have no right to have it."

Deacon and I not only talked, we also sang together. He was a basso profundo and had learned parts of two Italian operas he'd taped from the Hong Kong BBC. We sang first at the class's request: they wanted to add to their own repertoire which included "Doe, a deer, a female Deer," "Blowin' in the Wind," "Way down upon the Sewanee River," and "Que Sera Sera." So I taught Deacon "Summertime" from Porgy and Bess, and we sang it to the class. At one of the three parties of the year, I, along with everyone else, was asked, as is the custom, to perform a dance or a song or a Kung Fu move. Deacon and I sang "Santa Lucia" in Chinglishitaliano, he with such tremulos and sighs that I expected him to break into sobs at any minute.

We sang "Santa Lucia" at my farewell party too. All my students were there, shucking peanuts and drinking orange soda (they called it orange juice) and cheap Chinese beer that tasted as if it were mixed with apple cider. They stood and clapped as I entered. Wellington, tallest and most handsome "boy" in the class, presided. He thanked me for my "cordial teaching" and my erudition and "charity heart." Araminter assured me that they would never forget me and of the students' eternal gratitude and everlasting respect and announced their great grief at losing me. Gordon gave a Kung Fu demonstration, Margaret and Dorothy sang a duet of "My Bonnie Lies over the Ocean," Bruce recited "Annabelle Lee," Holmes played the harmonica, George and Sherman performed a Cross-Talk, a sort of comic linguistic routine satirizing the policy of requiring short hair and non-Western clothes. They portrayed a gatekeeper at a factory who refuses admittance to a woman because of her long hair. She offers to tie it up with "robber bands" after being instructed to "bandit." George and Sherman coached us "to keep smiling on our face," and at the end they bid us a "night good" "from the heart of my bottom." The entertainment concluded with "Santa Lucia" by Deacon and me. I gave a little speech assuring them that they would be forever dear to me; that I had been honored to be their teacher and that together we had advanced the cause of peace. Dorothy cried.

Deacon gallantly escorted me home. (There were snakes about, he said. He didn't say, since the Chinese were expected not to bring bad news to the foreigners, that a girl had been raped the week before. As far as I know, it was the only rape case that year.) As we walked I taught him "'Tis a gift to be simple,Tis a gift to be free," but gave up on the duet from The Pearlfishers. Deacon asked if I thought the millions of fireflies flickering over the rice paddies were ghosts.

The day before I left, I found Deacon sitting on the steps in front of my door. He was waiting to tell me that he had been asked to stay at the Institute to teach. The committee said that the confirmation of acceptance that he had received from the music school in Beijing had been bogus; that in fact he had failed the examinations. They wished, therefore, that he would stay at the Institute, since Chinese schools needed to improve the quality of the teachers in order for the modernizations to be realized. China, the party chairman said, was his mother, whom he must serve. They said they knew he had a friend, and they would be willing to see to it that she was assigned to Guangzhou if he accepted the job. They reluctantly granted his request for three hours to consider his decision about his lifetime.

He asked me what he should do. If he refused this job, he said, they would give him a terrible job or no job at all, maybe, and he would lose the jade statue. But he didn't want to be a teacher. He had no aptitude for it. No interest in it. His English was poor. The pay was poor; chances of advancement were poor, too. Could I get him into Dartmouth? Could I be his sponsor? Could I get him a job? I promised to do what I could. We dirank some brandy. "Mei you quan chi," he said at last in a tired, resigned voice. "It doesn't matter. It doesn't matter."

In his last letter to me here, Deacon wrote about a dream he had had of his grandmother, who said, "Since Adam and Eve with the sins came the world, you are doomed to have sins. But if you are willing to send the stones to Jesus, he will burden them on his own back." Deacon continues, "At that point I looked through the window and I saw the White House in America was face to face with me. What is the matter, I said. The speaker was not my grandmother. She had become my beloved Dr. Sears. She was teaching us American literature, explaining the Bible, and we were in America in my dream."

Deacon took the job. The snow in the west is still pure, and the jade statue is still in Szechwan. Boris's story is told mostly in his own words, from his journal and with his permission. Deacon and Boris often walked around the campus hand in hand, and at the party, late in the year, where waltzing was allowed for the first time in twelve years, Deacon attempted to teach Boris to tango. In China, people of the same sex kiss and caress, embrace, walk arm in arm, hand in hand, waltz together. Deacon and Boris were a curious pair. Deacon was tall for China, a 26-year-old Northerner, rather cosmopolitan; Boris was a caricature of the kamikaze pilot in an old World War II movie. In the West, he would have been a "hick." He had fuzzy teeth, small thick glasses with broken black frames pieced together with electrical tape. He wore thin white shirts and baggy black pants and brown plastic sandals. He spoke in nasal tones and sniffed.

One day in October I met him as I walked along the paths, avoiding the ducks who were being herded by a boy, who, according to the Chinese constitution, should have been in school with many other working children. Boris said he would escort me to the bus stop and advised me to push hard to get on, otherwise I might not be able to fit in or I might get caught in the door and be half in and half out. He apologized profusely for the rudeness of people who failed to give me, "an aged woman and a distinguished professor," a seat, but since the Cultural Revolution ... He sighed.

I complimented him on his essays, and I remembered that he was an editor of a controversial campus magazine in English, The Looking Glass. Boris said the essays were "feeble" and apologized again. He explained that he was studying four languges that year English, Japanese, French, and German and he had to work hard and neglect his editorials, but he had no regrets, for "knowledge is power." I said his parents must be proud of him. He said his parents were illiterate peasants, but their children weren't: his sister was a doctor; his brother was an engineer; he hoped to be a professor.

The bus was late. Boris waited with me, shielding me from the sun with my umbrella. He said I should know he had often made his parents sad. He was a "naughty boy." He hated kindergarten, where he only learned "Long live Chairman Mao." He kicked the teacher who tried to beat him. When he was ten or so, he had run away to Tungbai to avenge the death of the heroes of a novel he had read. He had stowed away on several trains and traveled hundreds of miles, begging for food, at one point eating only watermelon rinds and seeds for several days. At last he arrived in Tongbai and became dejected when no one knew the names of the heroes and heroines and the place was "nothing special." My bus finally came; I didn't get to know Boris any better until he began to keep a journal. I learned that Bor- is's prodigious appetite for reading couldn't be satisfied during daylight hours, and since the electricity was cut off at 10:00 p.m., Boris began to read under the faint red night light in the bathroom, where rats came to drink. He says, "As I sat on the floor of the bathroom under the light, I wondered why Francis Bacon was described by Pope as 'the wisest, brightest and yet meanest of mankind'; why John Dry- den always turned with the tide and placed himself on the winning side. I admired Thomas More, who met his death on the scaffold with great courage and raillery, and Daniel Defoe, who sang his 'Hymn of Pillory' as he was made to stand in the pillory. I at last found myself in John Milton's Samson Agonistes. Merged in illusion, I sensed More, Satan, Samson, and Defoe approaching me, and our hearts began to beat at the same frequency, and the blood ran from their veins into mine. Arm-in-arm, shoulder-to-shoulder, braving the turmoil of the world, we laughed . . . And in a sudden ecstacy we merged into one person."

Boris's reverie in the bathroom was interrupted by the footsteps of a fellow student, Abbott, who sat in the back of my class, reading T.S. Eliot and brooding about suicide. Boris was startled, because if Abbott were caught, he might be reported to the political instructor, "a power seeker who does good things only to distinguish himself." But Abbott was sympathetic. "He looked around to see if anybody was there and then put his mouth near my ear and told me the political instructor had said I was a reactionary. I tried to appear unaffected. 'What reasons does he have to say I am a reactionary?'

" 'I don't know. And when we said you keep a very good academic record, he replied that you only know several more words than others.'

"I was angry that he should have profaned knowledge, which I regard as the most sacred thing.

" 'Please don't tell what I've told you; otherwise, I'll be in terrible trouble with the political instructor,' begged the other student.

"Milton and More and Defoe were gone. I thought of Yu-loke, the great fighter during the Cultural Revolution. He loved the country and loved the people and loved truth; he hated the poverty of the country and he hated the ignorance of the people and he hated the distortion of the truth. He refused to be silent. He was executed. And Zhang-zixin, who defended truth and died for truth during the Cultural Revolution. In prison she composed a song of truth. On the execution ground she sang this song. While she was singing, her throat was cut into halves. Her blood splashed the enemy. I feel my blood run cold; thinking of you, I feel myself fighting in a battlefield."

Boris had to give up studying in the bathroom. The lights were turned off there too, because we had exceeded our electricity quota. He moved outside to study with the cicadas and the "fireworms with their greenish lanterns," but the mosquitoes became intolerable. So he applied the L.L. Bean insect repellant I had given him and stood under streetlights reading Paradise Lost but these lights go out at 11:30. Once he felt his way in the dark up the stairs of an unfinished building to a light on the roof, but two workers were living there. He returned to the bathroom with a flashlight, and at last snuck into the library reading room, which was open until 12:30 a.m., for teachers and postgraduates. There he continued reading Milton and the philosophers who "had written on behalf of liberation, revolution, and freedom. I must read, for he who would make history, must study history."

The answer to Boris's question about the political instructor's accusation wasn't long in coming. Soon afterwards the political instructor spoke at a compulsory meeting. " 'I am to emphasize the discipline. Some students have recently behaved badly, been absent from classes and morning exercises, late for meetings and for going to bed. I order every monitor to announce the absentees to the class every week, then submit rolls to me, and every two weeks I shall announce the absentees to the whole grade. Every dormitory cadre will register those who make noise, talk, or do not go to bed before 10:30 and will announce them to the dormitory every week and then submit the rolls to me.' "

Boris stopped listening. He thought, "I once dreamed that many people came to visit and learn from our advanced unit. Rousseau, the French philosopher, came too. I boasted of our decent order to him, but he sneered, 'A veritable prison.' In an illusion I saw Rousseau change into one of the students in this prison. He resisted. 'I am not a slave,' he shouted. But it was only a dream. Here, in reality, Rousseau couldn't come. But I? 'I am not a slave either,' I whispered to myself as I took my hands off my ears."

The political instructor was still foaming and snarling. " 'Recently I read two magazines. Songbird [a Chinese magazine published by the sanctioned Youth League Committee] is good very, very good. Even the working staff read it actively, while the so-called periodical, The Looking Glass, is only waste paper. It can only lead the students astray. The editors ... let off their personal dissatisfactions, grievances, and unhealthy ideas . . . They write about meals, hot water, supply service. But among the working staff, who can understand English? The magazine is of no avail, unable to solve any problems. The editors and writers are sheer anarchists and humanists. They scatter the magazine as leaflets to spread seditious ideas. Students, you should be fully aware that whoever writes such seditious articles cannot be qualified morally. If not qualified morally, they can't graduate.' "

Ivan comments: "It is no surprise that the political instructor was not forced to stop, for four-fifths of the students are cadres. And every cadre has his specific job as every carrot has its pit to grow in. The instructor dominates all his cadres from the Chairman of the Student Union to the cadres of the toilets to form a very effective network. If a cadre expresses his different views, he will be replaced. The political instructor has created 45 new rules, for the rules and regulations of the Institute are not sufficient to enforce his authority. The students seem quite willing to accept the rules. But Rousseau, not in the hands of the political instructor, has come out to express his wisdom and foresight, 'Man is born free, but everywhere he is in chains.' "

The political instructor had just begun the fight. He requested the collective leadership of the Institute to break up the unity of the editors by appealing to some as "comrades"; to replace the current editors with his own flunkies. He unjustly accused one of the editors of lying, a moral offense comparable to filching money from the Salvation Army pot; he posted new versions of the magazine articles in question, edited by the Division of Propaganda and approved by the Bureau of Public Tranquility. Ivan says: "The political instructor hankers over power. So do I. But the way I take is different from his. He shoulders and elbows his way forward, and kicks those who are in his way. I plough forward for knowledge. Knowledge is power. He gets the power to dominate; I get the power to serve. He may kick me, but he best be careful not to kick me too hard, for I do not fear him nor the loss of my life."

Ivan wasn't exaggerating. He held fast and launched his own attack. He appealed the case to the collective leadership, even though, as he says, "the political instructor is a party member and officials here are all colleagues and neighbors. [All of the faculty, Chinese and foreign, lived within a few blocks of each other.] They will continue to work together after our graduation. Would they be conscientious enough to criticize the political instructor? Most officials shelter and shield one another. Due to the destruction of the great Cultural Revolution, the officialdom is decaying." He argued his case valiantly in print as well. He wrote: "The political instructor's condemnation of the writers of The Looking Glass is unreasonable. As our supervisor says, 'A good mirror always gives a true reflection of what there is. No distortion, no exaggeration, and no diminution, just the bare facts of life.'

"Furthermore, nobody dares say that he never makes mistakes as the political instructor has. We will not stop working because of making mistakes, as a person will not stop walking because of tripping and falling. As the former Chairman Mao Tze-tung said, 'Let one hundred flowers blossom; let a hundred schools of thought contend.' The more the truth is debated, the clearer it becomes. The political instructor has made mistakes. He has, with unsufferable arrogance, unjustly accused us of being criminals. He fabricated accusations. He tried to replace us. He threatened us. And he has not acknowledged his mistakes. One has to make mistakes. From a Marxist point of view, validity and mistake are the unity of opposites. The law of the unity of opposites is the fundamental law of the universe. If one presumptuously asserts that he never makes mistakes, his assertion should be taken as the ravings of a madman.

"We demand that the political instructor redress his wrong of making the students believe we are liars by confessing his . mistake publicly. We demand that the writers of this magazine be allowed to continue to write freely and expose the drawbacks of our Institute without meddling from the mistaken political instructor."

The die was cast. As Ivan lay in his bunk bed that night, he reflected: "I thought of the millions of Chinese history, all the great men of the past, their valour, their sacrifices, and their glorious deeds. I pondered over why Japan and Germany had so quickly rebuilt their countries and forged ahead with giant strides, while China, the great ancient country, had fallen behind. I was distressed about the Chinese people's spiritual backwardness, their passivity and inertia. I resolved to help scatter the forces that were stifling the people's vitality, and to flay China's weaknesses, turn the silent China into an articulate China. China's history is full of bloodstains. But we have survived. Those who died for its integrity and those who would fight for its revival were the nation's backbone and mainstay. I would be a man of unyielding integrity; I would be a fighter for revolution and reform. Difficulties and obstructions will be many. But I will be helped by my passion for truth, my love for my people and my devotion to my country.' At last report, Ivan's and the other editors' fight for reform had been partially successful: the political instructor had recanted after he had been criticized by the Party Secretary, the highestranking official at the Institute, as "too simple and arbitrary" in his action. Although all articles must be approved by a committee, some freedom of the press has been granted. But Ivan and his comrades, far and away the best students in the grade, have not, according to Ivan's most recent letter, been awarded any of the few scholarships for graduate study, and they are fearful about their assignments.

I left Guangzhou Foreign Language Institute on July 15, 1984. My students and colleagues came to my flat for a farewell ceremony. They brought paintings, fans, scrolls, chops and tea, and Priestly sang, "Home on the Range," and Golden Fish set off firecrackers. When the car for the airport tooted, Ivan was called on to recite a poem by Langston Hughes.

Hold fast to dreams. For if dreams die Life is a broken-winged bird That cannot fly. Hold fast to dreams. For if dreams go Life is a barren field Frozen with snow.

When I came back up here to Dartmouth, things seemed, as Fitzgerald once wrote, "material without being real." Had I always drunk water from a faucet? Had Thayer always had an all-you-can-eat policy? Had I always had so many books I didn't need? Had my desk always been big enough to play ping pong on? People casually ask me "What's China like?" I've casually answered "unreal" or "utterly other or "upside down." That was not, in essence, either factual or true. I should have said China was a terra incognita that I knew by heart.

Desks, books, and intent students were elements of the Chinese classroom common toany educational setting. But the authorfound much more that was unfamiliar.

My first impressions ofthe other side of the worldthat day were of utterotherness. Nothing wasfamiliar.

If you fell in love beforegraduation, your unitwouldn't give youpermission to marry, andupon graduation youmight be sent to Tibet andyour friend to Beijing.Forever.

I gave a little speech assuring them that they would beforever dear to me; that I had been honored to be theirteacher and that together we had advanced the cause ofpeace. It sounds cliched. But I meant it.

Boris's prodigious appetite for reading couldn't besatisfied during daylight hours, and since the electricitywas cut off at 10:00 p.m., Boris began to read under thefaint red night light in the bathroom, where rats came todrink.

"One has to make mistakes. From a Marxist point ofview, validity and mistake are the unity of opposites. Thelaw of the unity of opposites is the fundamental law ofthe universe. If one presumptuously asserts that he nevermakes mistakes, his assertion should be taken as theravings of a madman."

"I plough forward for knowledge. Knowledge is power.He [the instructor] gets the power to dominate; I get thepower to serve. He may kick me, but he best be carefulnot to kick me too hardfor I do not fear him nor the lossof my life."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleEfrain Guigui: Well-tempered conductor

October 1985 By Georgia Croft -

Sports

SportsOn the road to Cambridge. The Harvard Game

October 1985 By Jim Kenyon -

Class Notes

Class Notes1979

October 1985 By Burr Gray -

Article

ArticleThomas V. Seessel '59: "It's okay to say 'No' "

October 1985 By Rex Roberts -

Class Notes

Class Notes1982

October 1985 By Emily P. Bakemeier -

Article

ArticleRocky Mountain Institute: a 20th-century castle built by hand

October 1985

Priscilla Sears

Features

-

Cover Story

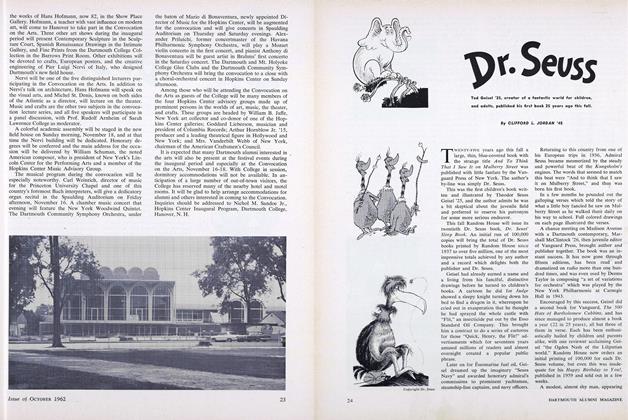

Cover StoryThe Big Day Draws Near

OCTOBER 1962 -

Feature

FeatureRobert Huke Professor of Geography 150 catfish in a single dame

January 1975 -

Cover Story

Cover StorySENIOR FENCE

MARCH | APRIL 2014 -

Feature

FeatureThe U.S.-Canadian Relationship

DECEMBER 1972 By JOHN SLOAN DICKEY '29 -

Feature

FeatureJohn Singer Sargent: Last of the Great Portrait Painters

November 1983 By Richard Stuart Teitz