"Hast Thou Entered into the Treasures of theSnow?" Job: 38:22

On one of those annunciatory October mornings when the light was absolutely pure and clear, I saw the Canada geese arrowing down the sky toward the Louisiana bayous. I waved to them and wished them well, but I couldn't watch them for long because I was driving over Mt. Cube, late as usual, on my daily 35-mile trek in to Dartmouth. I remembered those migrating geese today, on a dark December morning, as I was passing the crooked farmhouse where the lady in the cotton apron sells flowers. Her hand-lettered sign, "Gladiolas 20 cents each" was iced over. "What am I doing," I thought, "driving over the mountain on slick roads at 7:00 a.m.? I should have followed the geese." Students and alumni often ask me the same thing. "Why do you stay up here in the winter? How can you stand driving back and forth between Wentworth and Hanover every day in stormy weather?"

Lots of things do leave, of course: The geese, the monarch butterflies, the red-tail hawks, the indigo buntings. After the trees flare up red and gold, the flames fall, and the fires are banked for the winter. And the summer people pull down the shades and tack up a notice: "Keep Out. This Property Protected by the State Police."

I used to be a part-timer, too, leaving in September for the suburbs and life-as-lived-in-NewYorker-advertisements. I'd come back for a few weekends to reassure myself that life still had a chance, despite the Armageddon scrawled on the wall in broad daylight by modern major generals. But it made me feel like Marie Antoinette at Versailles playing in a Faberge simulation. So finally I moved up full-time.

Of course many full-time people take winter vacations. They go to the Caribbean in February to recover prematurely the warmth and the light. I don't even want to do that. It's like forcing tulip bulbs in January. De-naturing. Deceiving, too, in a way, giving the illusion of control a kind of thermostat mentality. I'm even secretly glad when we have to close the schools or once in a blue moon the roads. I'm reminded of the Book of Job. "Now we'll see," I think, "who enters into the treasures of the snow."

The snow comes early up here out of a spindrift sky often before Thanksgiving covering bare November like a comforter. The mice tunnel under the snow to their summer storage, free from want and fear of owls. The yellow-breasted grosbeaks gather on the feeders in the white garden, and the foxes and pheasants come close to eat the corn kernels we sprinkle under the apple trees in the back field. By Christmas it's below zero, and we quote thermometer readings like baseball scores: Canaan 22 below, South Strafford 30 below, the summit of Mt. Washington 46 below.

Once the snow has fallen, the light that seemed at first, in November, strained through milk glass becomes stronger, dancing like Shiva, flashing fierce and metaphysical, signifying something surely. Some mornings the air glitters with ice crystals, "as if," says Frost, "the dome of heaven had fallen." The phenomena is called "bridal veil." I've only seen it once. I wanted to stop the car and get out into it, or swallow it, or say a prayer.

In a poem called "The Snowman," Wallace Stevens says when you have "a mind of winter" and get down to the quick of the cold, you behold "Nothing that is not there and the nothing that is." When I lived in warmer climes, I understood "Nothing" in the sense of meaninglessness and voidness. Up here I've changed my mind. The "nothing that is" may be, as the Buddhists say, the sublime nowever source of everything the unceasing, unchanging, all prevading suchness.

That's why I stay: to be, in "the treasures of the snow."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

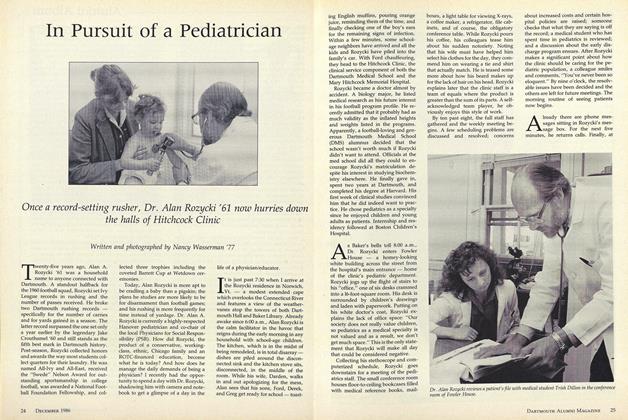

FeatureIn Pursuit of a Pediatrician

December 1986 By Nancy Wasserman '77 -

Feature

FeatureLawyers, Liberal Arts, and the Cold War

December 1986 By Weyman I. Lundquist '52 -

Feature

FeatureRichard Hovey: The Incomplete Arthurian

December 1986 By Daniel P. Nastali -

Feature

FeatureSnowmaking at the Dartmouth Skiway: Taking the Wonder Out of Winter

December 1986 By Lee Michaelides -

Article

ArticleMarianne Alverson: At home in many worlds

December 1986 By Lee McDavid -

Article

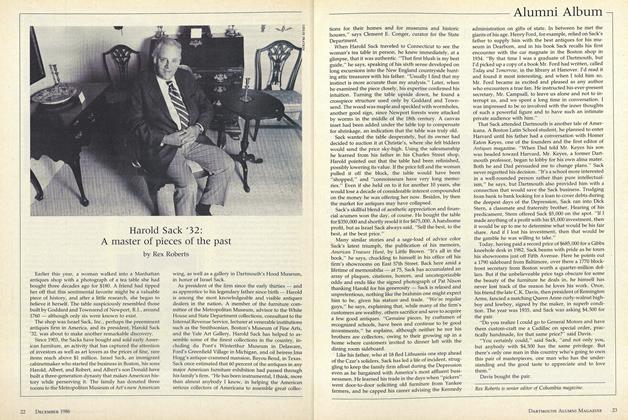

ArticleHarold Sack '32: A master of pieces of the past

December 1986 By Rex Roberts