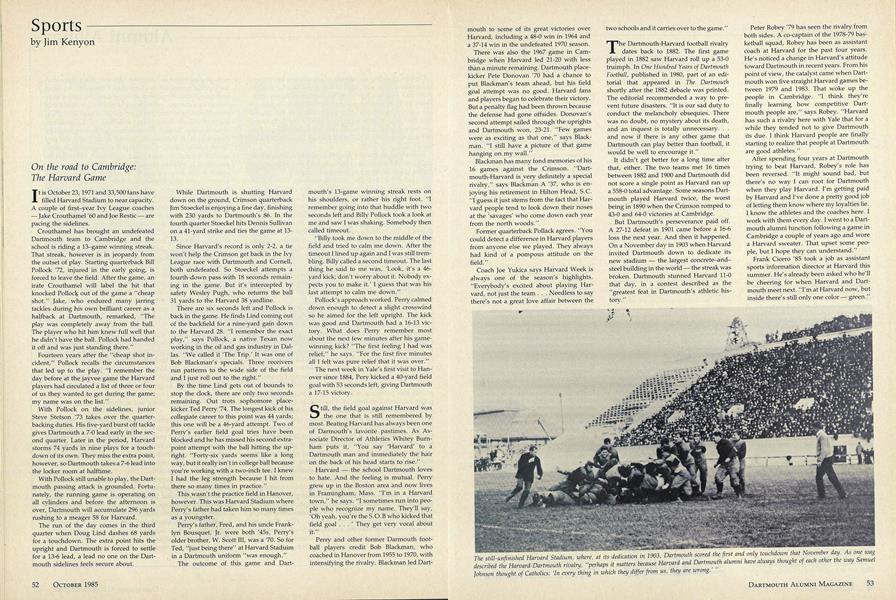

It is October 23,1971 and 33,500 fans have filled Harvard Stadium to near capacity. A couple of first-year Ivy League coaches Jake Crouthamel '60 and Joe Restic are pacing the sidelines.

Crouthamel has brought an undefeated Dartmouth team to Cambridge and the school is riding a 13-game winning streak. That streak, however is in jeopardy from the outset of play. Starting quarterback Bill Pollock '72, injured in the early going, is forced to leave the field. After the game, an irate Crouthamel will label the hit that knocked Pollock out of the game a "cheap shot." Jake, who endured many jarring tackles during his own brilliant career as a halfback at Dartmouth, remarked, "The play was completely away from the ball. The player who hit him knew full well that he didn't have the ball. Pollock had handed it off and was just standing there."

Fourteen years after the "cheap shot incident," Pollock recalls the circumstances that led up to the play. "I remember the day before at the jayvee game the Harvard players had circulated a list of three or four of us they wanted to get during the game; my name was on the list."

With Pollock on the sidelines, junior Steve Stetson '73 takes over the quarterbacking duties. His five-yard burst off tackle gives Dartmouth a 7-0 lead early in the second quarter. Later in the period, Harvard storms 74 yards in nine plays for a touchdown of its own. They miss the extra point, however, so Dartmouth takes a 7-6 lead into the locker room at half time.

With Pollock still unable to play, the Dartmouth passing attack is grounded. Fortunately, the running game is operating on all cylinders and before the afternoon is over, Dartmouth will accumulate 296 yards rushing to a meager 58 for Harvard.

The run of the day comes in the third quarter when Doug Lind dashes 68 yards for a touchdown. The extra point hits the upright and Dartmouth is forced to settle for a 13-6 lead, a lead no one on the Dartmouth sidelines feels secure about.

While Dartmouth is shutting Harvard down on the ground, Crimson quarterback Jim Stoeckel is enjoying a fine day, finishing with 230 yards to Dartmouth's 86. In the fourth quarter Stoeckel hits Dennis Sullivan on a 41-yard strike and ties the game at 13-13.

Since Harvard's record is only 2-2, a tie won't help the Crimson get back in the Ivy League race with Dartmouth and Cornell, both undefeated. So Stoeckel attempts a fourth-down pass with 18 seconds remaining in the game. But it's intercepted by safety Wesley Pugh, who returns the ball 31 yards to the Harvard 38 yardline.

There are six seconds left and Pollock is back in the game. He finds Lind coming out of the backfield for a nine-yard gain down to the Harvard 28. "I remember the exact play," says Pollock, a native Texan now working in the oil and gas industry in Dallas. "We called it The Trip.' It was one of Bob Blackman's specials. Three receivers run patterns to the wide side of the field and I just roll out to the right."

By the time Lind gets out of bounds to stop the clock, there are only two seconds remaining. Out trots sophomore placekicker Ted Perry '74. The longest kick of his collegiate career to this point was 44 yards; this one will be a 46-yard attempt. Two of Perry's earlier field goal tries have been blocked and he has missed his second extrapoint attempt with the ball hitting the upright. "Forty-six yards seems like a long way, but it really isn't in college ball because you're working with a two-inch tee. I knew I had the leg strength because I hit from there so many times in practice."

This wasn't the practice field in Hanover, however. This was Harvard Stadium where Perry's father had taken him so many times as a youngster.

Perry's father, Fred, and his uncle Franklyn Bousquet, Jr. were both '4ss. Perry's older brother, W. Scott III, was a '70. So for Ted, "just being there" at Harvard Staduim in a Dartmouth uniform "was enough."

The outcome of this game and Dartmouth's 13-game winning streak rests on his shoulders, or rather his right foot. "I remember going into that huddle with two seconds left and Billy Pollock took a look at me and saw I was shaking. Somebody then called timeout.

"Billy took me down to the middle of the field and tried to calm me down. After the timeout I lined up again and I was still trembling. Billy called a second timeout. The last thing he said to me was, 'Look, it's a 46yard kick; don't worry about it. Nobody expects you to make it.' I guess that was his last attempt to calm me down."

Pollock's approach worked. Perry calmed down enough to detect a slight crosswind so he aimed for the left upright. The kick was good and Dartmouth had a 16-13 victory. What does Perry remember most about the next few minutes after his gamewinning kick? "The first feeling I had was relief," he says. "For the first five minutes all I felt was pure relief that it was over."

The next week in Yale's first visit to Hanover since 1884, Pery kicked a 40-yard field goal with 53 seconds left, giving Dartmouth a 17-15 victory.

Still, the field goal against Harvard was the one that is. still remembered by most. Beating Harvard has always been one of Darmouth's favorite pastimes. As Associate Director of Athletics Whitey Burnham puts it, "You say 'Harvard' to a Dartmouth man and immediately the hair on the back of his head starts to rise."

Harvard the school Dartmouth loves to hate. And the feeling is mutual. Perry grew up in the Boston area and now lives in Framingham, Mass. "I'm in a Harvard town," he says. "I sometimes run into people who recognize my name. They'll say, 'Oh yeah, you're the S.O.B who kicked that field goal . . . ' They get very vocal about it."

Perry and other former Darmouth football players credit Bob Blackman, who coached in Hanover from 1955 to 1970, with intensifying the rivalry. Blackman led Dartmouth to some of its great victories over Harvard, including a 48-0 win in 1964 and a 37-14 win in the undefeated 1970 season.

There was also the 1967 game in Cambridge when Harvard led 21-20 with less than a minute remaining. Dartmouth placekicker Pete Donovan '70 had a chance to put Blackman's team ahead, but his field goal attempt was no good. Harvard fans and players began to celebrate their victory. But a penalty flag had been thrown because the defense had gone offsides. Donovan's second attempt sailed through the uprights and Dartmouth won, 23-21. "Few games were as exciting as that one," says Blackman. "I still have a picture of that game hanging on my wall."

Blackman has many fond memories of his 16 games against the Crimson. "Dartmouth-Harvard is very definitely a special rivalry," says Blackman A '37, who is enjoying his retirement in Hilton Head, S.C. "I guess it just stems from the fact that Harvard people tend to look down their noses at the 'savages' who come down each year from the north woods."

Former quarterback Pollack agrees. "You could detect a difference in Harvard players from anyone else we played. They always had kind of a pompous attitude on the field."

Coach Joe Yukica says Harvard Week is always one of the season's highlights. "Everybody's excited about playing Harvard, not just the team . . . Needless to say there's not a great love affair between the two schools and it carries over to the game."

The Dartmouth-Harvard football rivalry dates back to 1882. The first game played in 1882 saw Harvard roll up a 53-0 truimph. In One Hundred Years of DartmouthFootball, published in 1980, part of an editorial that appeared in The Dartmouth shortly after the 1882 debacle was printed. The editorial recommended a way to prevent future disasters. "It is our sad duty to conduct the melancholy obsequies. There was no doubt, no mystery about its death, and an inquest is totally unnecessary. . . and now if there is any other game that Dartmouth can play better than football, it would be well to encourage it."

It didn't get better for a long time after that, either. The two teams met 16 times between 1882 and 1900 and Dartmouth did not score a single point as Harvard ran up a 558-0 total advantage. Some seasons Dartmouth played Harvard twice, the worst being in 1890 when the Crimson romped to 43-0 and 64-0 victories at Cambridge.

But Dartmouth's perseverance paid off. A 27-12 defeat in 1901 came before a 16-6 loss the next year. And then it happened. On a November day in 1903 when Harvard invited Dartmouth down to dedicate its new stadium the largest concrete-and- steel building in the world the streak was broken. Dartmouth stunned Harvard 11-0 that day, in a contest described as the "greatest feat in Dartmouth's athletic history."

Peter Robey '79 has seen the rivalry from both sides. A co-captain of the 1978-79 basketball squad, Robey has been as assistant coach at Harvard for the past four years. He's noticed a change in Harvard's attitude toward Dartmouth in recent years. From his point of view, the catalyst came when Dartmouth won five straight Harvard games between 1979 and 1983. That woke up the people in Cambridge. "I think they're finally learning how competitive Dartmouth people are," says Robey. "Harvard has such a rivalry here with Yale that for a while they tended not to give Dartmouth its due. I think Harvard people are finally starting to realize that people at Dartmouth are good athletes."

After spending four years at Dartmouth trying to beat Harvard, Robey's role has been reversed. "It might sound bad, but there's no way I can root for Dartmouth when they play Harvard. I'm getting paid by Harvard and I've done a pretty good job of letting them know where my loyalties lie. I know the athletes and the coaches here. I work with them every day. I went to a Dartmouth alumni function following a game in Cambridge a couple of years ago and wore a Harvard sweater. That upset some people, but I hope they can understand."

Frank Cicero '85 took a job as assistant sports information director at Harvard this summer. He's already been asked who he'll be cheering for when Harvard and Dartmouth meet next. "I'm at Harvard now, but inside there's still only one color green."

The still-unfinihed Harvard Sradium,where,at its dedication in 1903Dartmouth scored the first and only touchdown that November day. As one wagdescribed the Harvard-Dartmouth rialry, "perhaps it matters because Harard Harvard and Dartmouth alumni have always thought of each other the way SamuelJohnson thought of Catholics: 'ln every thing in which they differ from us, they are wrong.' "

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

Cover Story"Are the fireflies ghosts?"

October 1985 By Priscilla Sears -

Article

ArticleEfrain Guigui: Well-tempered conductor

October 1985 By Georgia Croft -

Class Notes

Class Notes1979

October 1985 By Burr Gray -

Article

ArticleThomas V. Seessel '59: "It's okay to say 'No' "

October 1985 By Rex Roberts -

Class Notes

Class Notes1982

October 1985 By Emily P. Bakemeier -

Article

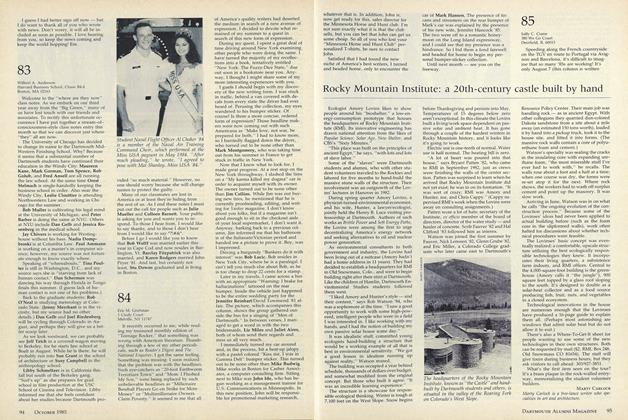

ArticleRocky Mountain Institute: a 20th-century castle built by hand

October 1985

Jim Kenyon

-

Sports

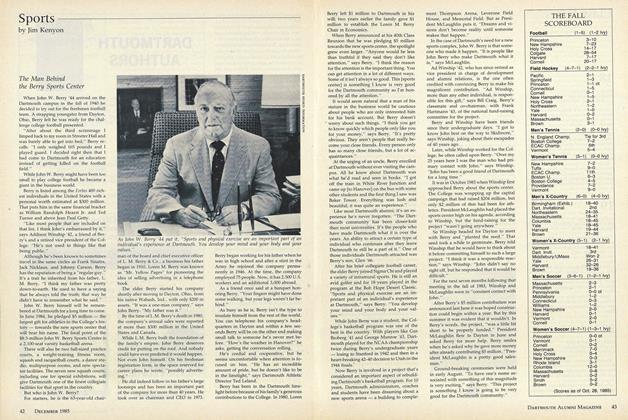

SportsThe Berry Sports Center: "A real shot in the arm"

NOVEMBER 1984 By Jim Kenyon -

Sports

SportsCormier: Committed coach

DECEMBER 1984 By Jim Kenyon -

Sports

SportsHockey awards

APRIL • 1985 By Jim Kenyon -

Sports

SportsCamps on campus

MAY 1985 By Jim Kenyon -

Sports

SportsNot-so-raw recruits

June • 1985 By Jim Kenyon -

Sports

SportsThe Man Behind the Berry Sports Center

DECEMBER • 1985 By Jim Kenyon

Sports

-

Sports

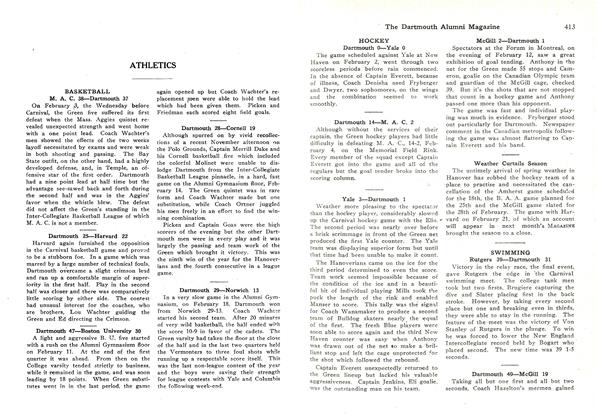

SportsDartmouth 1, Briarcliff 0

February 1925 -

Sports

SportsDartmouth 28—Cornell 19

March 1925 -

Sports

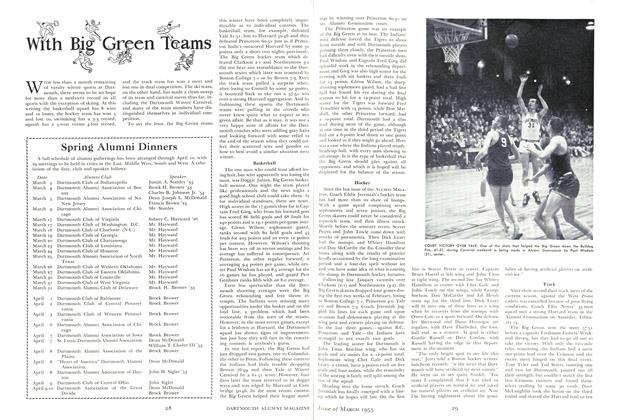

SportsWith Phil Sherman

March 1933 -

Sports

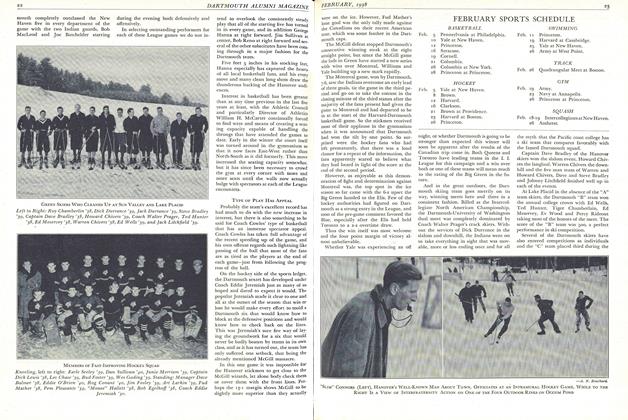

SportsTYPE OF PLAY HAS APPEAL

February 1938 By "Whitey" Fuller '37 -

SPORTS

SPORTS“A Dark Hole”

JANUARY | FEBRUARY 2017 By ADAM ESTOCLET '11 -

Sports

SportsBasketball

March 1953 By Cliff Jordan '45