Only God can make a tree, but Gil Fernandez '33 has come up with a good enough imitation to keep the ospreys coming back to the Westport River about as regularly as the swallows come back to Capistrano.

Actually, Fernandez and his wife, Josephine, have done much more for the ospreys than just provide them with suitable nesting platforms. Their involvement with the bird, a large, fish-eating hawk, goes back more than 20 years to 1963 when they first began to notice the diminishing numbers of ospreys along the Westport River estuaries, about five miles below their home in South Dartmouth, Mass. Members of the local bird club and the Massachusetts Audubon Society, the Fernandezes took regular walks along the river to birdwatch.

Noticing a few ospreys but concerned about their decreasing numbers, the Fernandezes notified Alan Morgan, head of the Massachusetts Audubon Society, of the ospreys' presence. With him, they explored the estuary to find a number of abandoned osprey nests and soon found themselves assuming responsibility for completing a survey begun by the Audubon Society to chart the annual number of returning ospreys.

"The survey indicated a decline of 10 to 15 percent each year among the returning ospreys," Fernandez said. "As part of the survey, we also gathered up all the eggs that didn't hatch and reported to the society how many were thin-shelled." The thin-shelled eggs turned out to be the key to the ospreys' declining numbers, Fernandez said. Laboratory studies on the eggs the Fernandezes collected showed that a derivative of DDT was causing a toxic condition in the female ospreys' internal organs. This resulted in the production of thin-shelled eggs which cracked or broke easily on the sharp sticks with which the ospreys' nests are constructed.

"The female bird was unable to coat the eggs with enough calcium to provide a thick enough shell," Fernandez said. "As a result, the eggs cracked. Air could penetrate the cracked shells, causing a hardening of the membrane that lines the shell. The youngster might develop fully, but he couldn't get out of the shell."

The results of the studies led to a ban on the use of DDT, Fernandez said, but in order to make the ospreys comfortable with the Westport River estuary as a nesting site, an auspicious reproductive climate had to be reestablished. So the Fernandezes collected dozens of eggs from the Chesapeake Bay area and placed them in the nests of unsuccessful mating pairs to provide them with offspring. And, to provide suitable nesting places, Fernandez began constructing nesting platforms to attract the birds who seek out dead or dying trees which have no foliage.

"They build their nests in a hit-or-miss fashion," Fernandez explained, "flying overhead and dropping the sticks into the bare branches at the top of a tree." The substitution of an 8- or 10-foot high pole topped with a flat platform thus suits the birds' needs admirably, Fernandez said, as long as the pole is located in the quiet, isolated area ospreys prefer. Fernandez has now placed more than 50 nesting poles along the estuary, and southeastern Massachusetts now has one of the largest concentrations of ospreys on the East Coast, with most of them breeding on platforms

Fernandez said he has been interested in birds ever since he married and moved to the country. "I'm not a golfer, and I hurt my ankle so I couldn't play tennis," he said. "Birding gets you out in fresh air, and it's something that can be done for just a few minutes at a time."

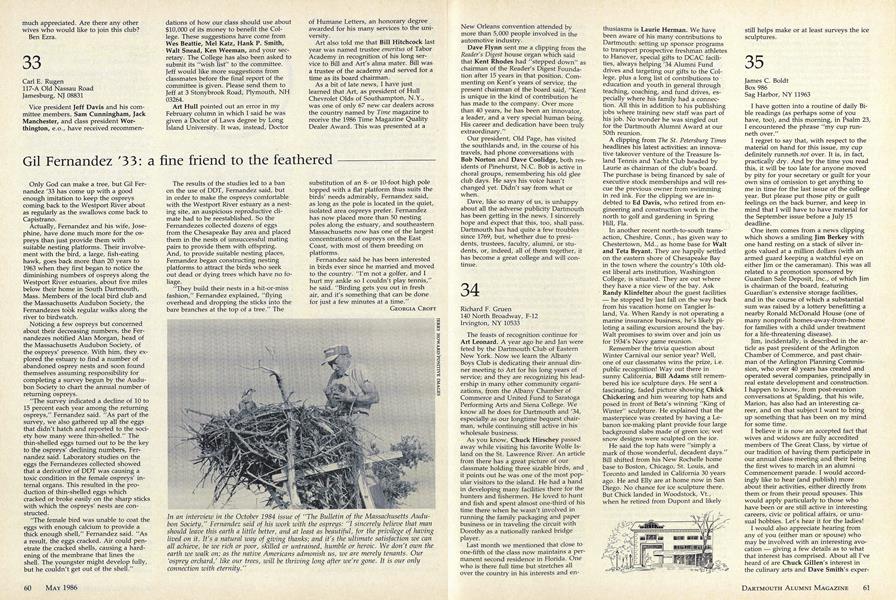

In an interview in the October 1984 issue of "The Bulletin of the Massachusetts Audubon Society," Fernandez said of his work with the ospreys: "I sincerely believe that manshould leave this earth a little better, and at least as beautiful, for the privilege of havinglived on it. It's a natural way of giving thanks; and it's the ultimate satisfaction we canall achieve, be we rich or poor, skilled or untrained, humble or heroic. We don't own theearth we walk on; as the native Americans admonish us, we are merely tenants. Our'osprey orchard,' like our trees, will be thriving long after we're gone. It is our onlyconnection with eternity."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

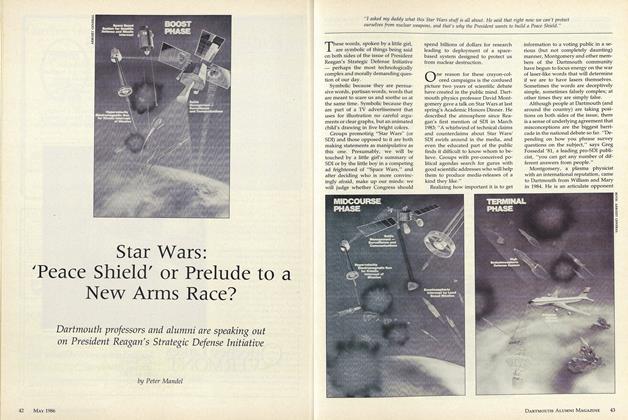

FeatureStar Wars: 'Peace Shield' or Prelude to a New Arms Race?

May 1986 By Peter Mandel -

Feature

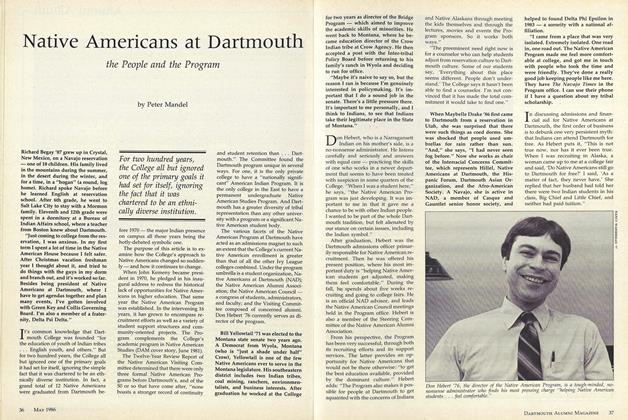

FeatureNative Americans at Dartmouth

May 1986 By Peter Mandel -

Cover Story

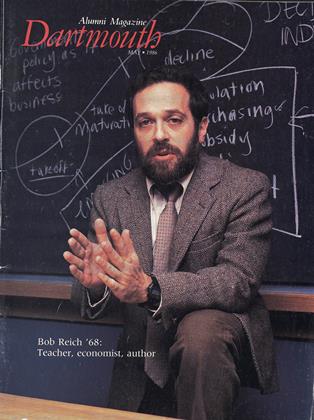

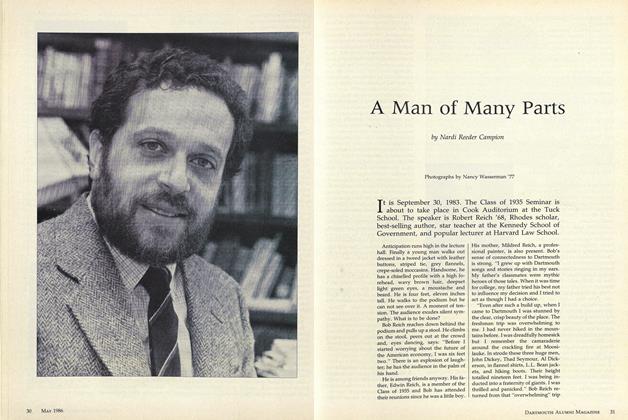

Cover StoryA Man of Many Parts

May 1986 By Nardi Reeder Campion -

Article

ArticleBack where it all began: Al McGuire at Dartmouth

May 1986 By Jim Kenyon -

Article

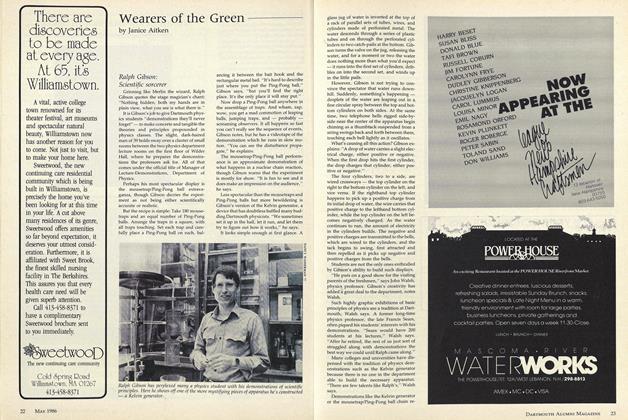

ArticleRalph Gibson: Scientific sorcerer

May 1986 By Janice Aitken -

Article

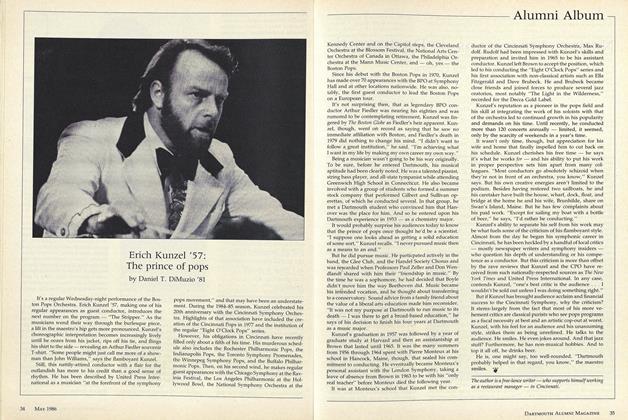

ArticleErich Kunzel '57: The prince of pops

May 1986 By Daniel T. DiMuzio '81

Georgia Croft

-

Article

ArticleFriend of the media

MAY 1985 By Georgia Croft -

Cover Story

Cover StoryBack on the Wall (where they belong)

SEPTEMBER 1985 By Georgia Croft -

Article

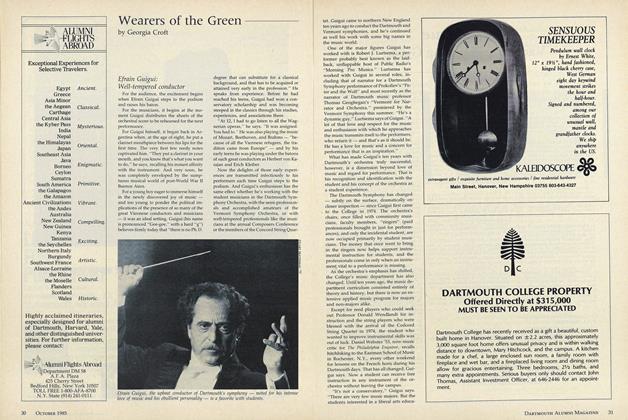

ArticleEfrain Guigui: Well-tempered conductor

OCTOBER 1985 By Georgia Croft -

Article

ArticleConnie Lambert: Doyenne of "The Daily D"

NOVEMBER • 1985 By Georgia Croft -

Article

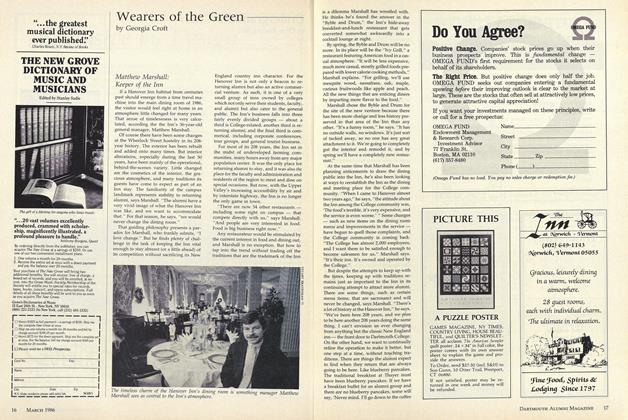

ArticleMatthew Marshall: Keeper of the Inn

MARCH • 1986 By Georgia Croft -

Article

ArticleCarl Thum: Teacher of how to learn

OCTOBER • 1986 By Georgia Croft