They came back with memories and experiencesthat have shaped their lives and ours forever.

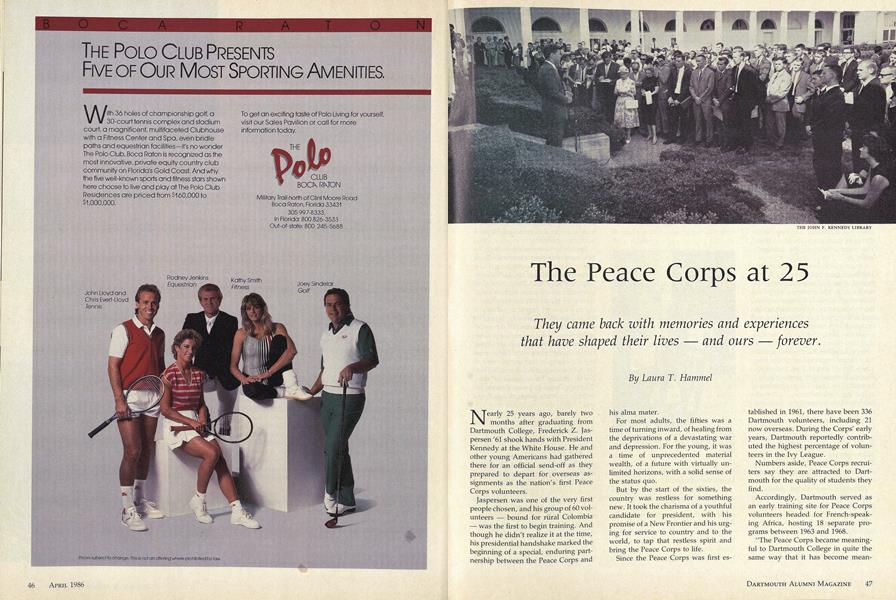

Nearly 25 years ago, barely two months after graduating from Dartmouth College, Frederick Z. Jaspersen '61 shook hands with President Kennedy at the White House. He and other young Americans had gathered there for an official send-off as they prepared to depart for overseas assignments as the nation's first Peace Corps volunteers.

Jaspersen was one of the very first people chosen, and his group of 60 volunteers bound for rural Colombia -was the first to begin training. And though he didn't realize it at the time, his presidential handshake marked the beginning of a special, enduring partnership between the Peace Corps and his alma mater.

For most adults, the fifties was a time of turning inward, of healing from the deprivations of a devastating war and depression. For the young, it was a time of unprecedented material wealth, of a future with virtually unlimited horizons, with a solid sense of the status quo.

But by the start of the sixties, the country was restless for something new. It took the charisma of a youthful candidate for president, with his promise of a New Frontier and his urging for service to country and to the world, to tap that restless spirit and bring the Peace Corps to life.

Since the Peace Corps was first established in 1961, there have been 336 Dartmouth volunteers, including 21 now overseas. During the Corps' early years, Dartmouth reportedly contributed the highest percentage of volunteers in the Ivy League.

Numbers aside, Peace Corps recruiters say they are attracted to Dartmouth for the quality of students they find.

Accordingly, Dartmouth served as an early training site for Peace Corps volunteers headed for French-speaking Africa, hosting 18 separate programs between 1963 and 1968.

"The Peace Corps became meaningful to Dartmouth College in quite the same way that it has become meaningful to host countries," wrote language professor John Rassias in a 1970 report to Peace Corps. "Its effect was not immediate or radical, but it stirred things up. People began to talk about it; it created a climate of controversy and self-evaluation."

Significantly, the Peace Corps was born on a university campus. When John F. Kennedy first publicly shared his vision of the new agency on October 14, 1960, it came as a challenge to some 10,000 students who had gathered outside the University of Michigan student union building to welcome him.

His aim, he said, was to give as many young Americans as possible the chance to reach out to the Third World and serve others at the grassroots level.

Kennedy's vision became reality. The Peace Corps relied on highly-motivated men and women who could readily pick up whatever additional skills they needed. Unquestionably, there were plenty of them waiting, unsure of their next step after college and intrigued by the notion of traveling to a faraway land to help people they only read about in books.

Kevin Lowther '63, regional director for Africare, summed up those early times. "The Vietnam War, civil rights, all of that seemed to be passing us by," he said. "The Peace Corps came along at just the right moment ... It really galvanized us for service to our country."

By September 1966, the number of volunteers and trainees serving at one time peaked at 15,556. Then came fullscale war in Vietnam and the Nixon years an era that took its toll on both the agency's political clout and the inclinations of many young Americans to work for the federal government. Although Peace Corps volunteers were not exempt from the draft, in most cases they were at least granted deferments.

Peter N. Geary '70, now a science teacher and basketball coach, recalled, "The fall of my senior year was the first lottery for the draft, and I was older than my draft number. By February, it was obvious if I didn't find something to do, I would be drafted.... I started investigating the Peace Corps, met with an on-campus recruiter, read the literature. From a personal standpoint, I saw I could do something constructive."

Another who felt the same way was A. Mead Over Jr. '66, now a health economist with the World Bank, who was "drafted" for Peace Corps duty by an ex-Marine at Dartmouth named John Rassias. After graduation, Over knew he could be hearing from Uncle Sam any day. Although he had never met Rassias, he had heard that he was directing the Peace Corps language programs at the College, and decided to stop by his office.

As Over recalled, "Rassias came bustling in, introduced himself, and before I could explain why I was there, he said he had to make a call. The call was to Peace Corps headquarters in Washington. He said, 'Hello, Elizabeth, I have a great kid sitting here in my office who would be perfect for the Upper Volta program.'

"I said, 'Wait a minute,' but he kept on. 'He speaks fluent French.' He didn't even know me. 'Listen, get started on the paperwork. His name?' With that John covered up the phone. 'What's your name?' he asked. When he hung up, he turned to me and said, 'Look kid, it's a volunteer proposition. You can pull out anytime."

Over, who went on to dig wells in the Upper Volta, found it to be the experience of a lifetime.

By the 1980s, the Peace Corps had weathered many storms and changed: it now pays more attention to such basic needs as food and shelter and to women in Third World development, and it works more closely with host countries and with multinational organizations.

The typical volunteer has matured as well. In 1962, the average age of volunteers was 25. It's nearly 30 today. In 1962, 60 percent of volunteers had liberal arts background and no other professional or technical skills to offer. Today only 15 percent of volunteers are liberal arts generalists and it's been tougher for them to get in.

Loret Miller Ruppe, the current director of the Peace Corps, explains: "The problem is that most countries are asking for what they think is the top trainee background a person with a .master's degree and 10 years teaching experience."

Those who have made it through the hurdles ip recent years seemed to have spent a long time researching Peace Corps programs and thinking through what two years in a Third World environment would mean to their lives.

Ellen G. Meyer '78, currently working on a master's degree in public policy at Harvard's Kennedy School of Government, researched 70 service organizations during her senior year before finally settling on the Peace Corps. Her short-term goals after college were to learn Spanish, find useful work in Latin America, and live in a rural Third World country for a period of time. "Dartmouth was a ripe environment to develop curiosity about things,", she said.

As the Peace Corps developed into one of the most significant forces in relations between the United States and the Third World, it offered new challenges for higher education. At the beginning, the Peace Corps turned to American colleges and universities for help in training volunteers, leaving much of the content and method of instruction to the individual schools to develop.

By 1963, more than 70 schools, including Dartmouth, were training volunteers, mostly during the summer. The benefits seemed obvious: it would save Peace Corps staff valuable time, it would involve a broader base of Americans in Peace Corps goals, and it would stimulate college faculty to develop new teaching methods and research interests.

The Peace Corps gradually shifted away from the college campuses because it found it cheaper to run its own programs overseas. In addition, they discovered that host countries could provide volunteers with better crosscultural and language training and a more realistic idea of what life would be like for two years.

But to be fair to the colleges and universities which did their best to meet the training challenge, not all the problems which bedeviled the early programs were of their making.

Parker Borg's experience is a case in point. His specific assignment was that of a teacher's aide in a small village outside Paracale in the Philippines. He finished six weeks of training at Penn State about the same day that Congress officially signed Peace Corps into law, September 22, 1961.

Borg '61, now Deputy Director of the Office of Counter-Terrorism at the state department, wrote about that training in an essay for a forthcoming book, Ask Not ... The Peace Corps at25. "As Penn State's ties with the Philippines were limited, four or five Filipinos from business schools in the Boston area were imported to provide a cultural introduction," he wrote. "We were subsequently told that Penn State was selected as our training site because of the correct image it presented to Congress, then considering the Peace Corps bill."

His group shipped out to the University of the Philippines in Los Banos for six more weeks of training. When they finished, he and his fellow trainees left for their rural villages "hoping to meet the same bright, articulate types we had known at Penn State and Los Banos," he wrote.

Two years later, David Dawley '63 started training for a community development assignment in rural Honduras. His group spent 12 weeks training at either the University of New Mexico in Albuquerque or in small towns outside Taos. Their 15-hour daily schedule was crammed full: six hours of Spanish; the usual courses in communism and U.S. government; endless batteries of stress tests and peer evaluations; drownproofing in pools; repelling off stadium walls; making adobe bricks; shearing and slaughtering sheep, killing chickens with a knife everything but what they really needed to know about Honduras. Apparently there were no Hondudran consultants available, and the only other volunteers to serve there were still at their posts. "There weren't answers to our questions," said Dawley.

However, by the time Stewart R. Henderson '81, now a consumer advocate in Washington, D.C., began training for an agricultural assignment in Mauritania, the preparation was very different. There was less emphasis on physical training and psychological testing and more emphasis on cultural awareness and technical skills. His group started out at a community college in Fort Valley, Ga., for six weeks of intensive instruction in basic agronomy. They then spent five weeks studying language in Mauritania's capital city, another week with volunteers already in the field, and then five more weeks living with local families.

Perhaps one of the brightest lights in the Peace Corps training experience was back in Hanover. That chapter began in 1963, and in typical early Peace Corps fashion, the College was given only four weeks from initial inquiry to arrival of trainees to mount a program.

The first group of 35 volunteers arrived in Hanover on July 12, 1963, and settled in Little Hall for six weeks. Robert Binswanger, the Peace Corps training officer overseeing the program, wrote, "In every respect, it was a superlative effort of which Dartmouth can be justifiably proud and that the Peace Corps will undoubtedly use as a model for future training programs requiring Romance language proficiency."

In 1964, the College proposed and ran the first Senior Year Program for the Peace Corps. It provided training at Dartmouth during the summers before and after the volunteers' senior year in college, as well as counseling on courses and extracurricular activities during the school year.

Perhaps more renowned was the College's language training for volunteers, especially under the indefatigable John Rassias after he took over as Dartmouth's Peace Corps language director in 1964. "It was a time of wild experimentation," he said. "The Peace Corps was a living laboratory. We had to come up with new teaching methodsto teach languages ..."

In 1966, Rassias traveled to Africa's Ivory Coast to set up the Peace Corps' first in-country language program. The following summer at Dartmouth, he created Peace Corps' first full language immersion program. From Rassias' dynamic experimentation came im-proved language instruction not just for volunteers, but for Dartmouth and the nearly 600 colleges that have since adopted the Rassias method.

When Congress formally approved the Peace Corps Act in 1961, it outlined three basic goals: (1) to provide trained manpower and technical assistance to Third World countries; (2) to promote better understanding of Americans; and (3) to educate Americans about the Third World. Twenty-five years later, those goals are intact. But how well they have been implemented is debatable.

What Dartmouth volunteers and others do agree on-almost to a person -is that the Peace Corps' greatest contributions have been in personal terms that cannot be quantified. They say their major accomplishments have been to introduce Third World residents to a new breed of American, eager to speak their tongues, willing to eat their food and sleep on their floors.

"I had the opportunity to affect only a few lives and not have any more impact than that," said William C. Marshall '63, currently headmaster of Applewild School in Fitchburg, Mass. "Seen that way, it seems miniscule. But to develop the kind of rapport with those people as I had the chance to do is enduring for life."

His thoughts typify the feelings of most Peace Corps volunteers. In terms of educating Americans about the Third World, many volunteers admit there is still much to do. "America knows nothing of the Third World," said Stewart Henderson. "Before I went, I thought of jungles, Tarzan and stuff when I thought of Africa. I thought people wouldn't know anything about America. I even brought matches, thinking there might be a shortage. What I found was that in the smallest village you could buy Marlboros. They listened to news on shortwave radios and asked questions about Kissinger and Nixon."

Volunteers such as Henderson say they have made some inroads talked informally with friends, written articles, given formal presentations and slide shows to high school and civic groups but probably could and should do more.

The Peace Corps' initial goal to provide trained manpower and technical expertise has proved more difficult to fulfill.

Though it seems clear that the Peace Corps has been helpful in making friends for the United States in Third World countries and in erasing some of the ugly stereotypes about Americans, it is not so clear whether their presence has resulted in many longterm material benefits. One of the important variables has been the assignments given to volunteers.

Talk to a volunteer who had a specific, well-defined job, and he or she usually can describe specific, well-defined results. P. Andrews McLane '69, partner in a Boston capital venture firm, helped drill about 25 water wells for villagers in Chad.

D. Scott Palmer '59, now chairman of Latin American and Caribbean studies at the Foreign Service Institute in Arlington, Va., helped plant 100,000 eucalyptus trees to serve as a permanent stock of wood for remote Indian communities in Peru.

As a teacher of health care and animal husbandry, Ellen Meyer taught 700 children how to use toothbrushes donated by the Honduran Ministry of Health. When she returned to her village several years later, children kept dragging out their bedraggled brushes as proof that they had not forgotten her advice.

But others, citing the real, desperate needs of Third World countries, want greater results. In 1978, Kevin Lowther and C. Payne Lucas published a book, Keeping Kennedy's Promise, which blasted the agency for failing to meet its first goal.

"The Third World is not a cultural sandbox in which young Americans may outgrow their ignorance of the world," they wrote. "The poor of this planet need more than sandcastles built by earnest foreigners; they need skills. Therefore, unless the Peace Corps is transformed into a respected source of technical assistance, it should humbly fold its tents."

One of their biggest complaints was with the large numbers of volunteers sent overseas to teach, especially the so-called TOEFL program, teachers of English as a foreign language.

Since the early days of the Peace Corps, more volunteers have been engaged in classroom education than in nearly all other projects combined. The reason for the emphasis, say Peace Corps officials, is that education is one of the crucial first steps to development and change in the Third World. There were, and still are, serious shortages of schools and teachers in many rural areas.

William Marshall taught English at a school in Imin'Tanout, a poor mountain village in Morocco. Twenty years later, he and his family returned to his old village on vacation. "I noticed a guy walking shyly behind me, looking like he wanted to say something to me," Marshall said. "I went into the old school and spent some time there. When I came out he was still there. Finally he came up and asked me if I was 'Monsieur Bill.' When I said yes, he began rattling off dialogues I had taught him 20 years ago. He had been one of my students and was a teacher himself now. He treated me to lunch and said it was the least he could do."

Lowther and Lucas acknowledged success stories like that of Marshall, but also point out in their book that there were a number of failures, too. It was presumptuous, they wrote, to assume that recent liberal arts graduates could become professional, competent teachers after only 10 weeks of training. "Teaching programs have served the Peace Corps by providing easy placement for thousands of generalist volunteers," they wrote. "Traditionally they have been slot fillers rather than agents of change in educational systems desperately in need of modernization."

Another difficult slot for volunteers was the vaguely-defined task of community development. According to the Peace Corps, the important thing in community development was not the specific projects or problems tackled, but that people learned to work together.

David Dawley had such an assignment in El Triunfo. "I was rolled out of a jeep, introduced to the mayor, a 70-year-old woman with a braid down her back. Someone had come to the village once and asked if they would like a Peace Corps volunteer. They said, 'Sure, what's a Peace Corps volunteer?' "

It took a long time for his village to get their answer. "We were told to go in, get to know the people, and the factions and the needs," Dawley said. "For me the first thing to do was getting out and mixing; just talking to people, sitting on stoops.... I was very conscious not to move too quickly."

His patient, low-key approach paid off. The town Dawley was assigned to and surrounding hamlets planned and built a health clinic and two credit unions which lasted for many years after he had gone. "The clinic was not completely finished when I left, but I felt very comfortable leaving," said Dawley. "I had always known that the clinic was not the monument; the process was." Many others were not as patient and became frustrated, requested transfers, and tried to solve the problems themselves.

According to Thomas G. Johansen, Jr. '73, a CPA in Lebanon, N.H., the Peace Corps experience is a "profoundly shocking experience on all levels," and indeed it must be. In subtle and not so subtle ways, the Peace Corps stays a part of volunteers' lives long after their assignments end. Those from Dartmouth were no exception.

More than half of returned volunteers cite their service in the Peace Corps as the major determinant in their choice of careers, according to a 1977 survey. Many more say the service has had profound influence on the way they carry out their professional responsibilities, whether it is in the board room, the courtroom, or the classroom.

For Paul Tsongas '62, former U.S. senator, the Peace Corps became a standard by which to measure the rest of his life. "If I hadn't gone into the Peace Corps, I never would have gone into politics," he stated. "Politics was the only other thing that gave me that sense of spending my life correctly."

Perhaps most enduring of all are the invisible marks of Peace Corps service. Volunteers say the experience reaches deep inside they emerge as different people somehow, perhaps with different values or different ways of listening and responding to others, or maybe just different ways of evaluating themselves.

"The experience was tremendously valuable in helping me come to grips with myself," said Johansen. "Living in an environment where everyone's assumptions are different than your own, you are forced to examine your own, to examine the foundations. I was the only white person in my village for three years.... Sometimes 30 to 40 kids would follow me. You had a sense of always being on stage, and I dealt with it. It didn't stop me."

For William Marshall, the Peace Corps meant redefining his life's goals. "The Peace Corps helps you to realize the global nature of our existence," he said. "It forces you to go beyond yourself; it teaches you who you are and what you are in perspective.

"No one would have predicted that I would be doing the things that I am doing before I entered the Peace Corps," Marshall said. "I came from a fairly affluent background outside of Pittsburgh. The Peace Corps was pivotal to my life. It showed me what was important."

Reluctant to leave their villages entirely, many Dartmouth volunteers write to the families they befriended abroad or to other volunteers who replaced them. As the years pass, and the letters dwindle, they at least try to keep up with news about their assigned countries in papers or journals. And when they can, many go back to visit. They find they weren't forgotten.

"I had the most amazing homecoming," said Ellen Meyer. "I had written them that I was coming for a visit, but I arrived a day late due to transportation. As I walked down the path to the village, I saw a hundred children coming toward me over the crest of a hill. They were followed by adults with banners that said, 'Blessed be the God that brought Ellen back to us.' "

THE JOHN F. KENNEDY LIBRARY

The Dartmouth campus was the trainingsite for the first group of volunteers sent toGuinea.

William Marshall '63 (back row, middle) returned from Morocco with a wife, Donna, whowas another Peace Corps volunteer stationed overseas. To court her he had to travel 9 hoursby bus and train to Casablanca.

Paul Tsongas '62, on the Ethiopian townof Wollisso: "Any resemblance between myexpectations and reality was purely coincidental."

"The moon, the Peace Corps. Itwas a time of thrusting out inthe outer world."— Kevin G. Lowther '63

"Thad quite a baptism ... I had been grilled in French, but when I got to the town, I found that most people spoke Arabic or Berber." William C. Marshall III '63

"I visited the farm of an agriculture teacher shortly after I hadseen him demonstrate the use of fertilizer to his students at school. WhenI asked whether he fertilized hisfields, he said, 'Oh no, when the rainscome, all the fertilizer just washesaway.' I asked him how he could teachone thing and practice the other. Heanswered, 'I teach what the curriculum requires, and I grow rice the sameway my family has grown it for generations.' " — Parker Borg '61

"The people wanted to buy the A bricks to build the clinic. I thought that we should make them. . . . There was a vote, and I lost. I stormed out of the meeting. One of my friends followed me. He said, 'But David, you were the one who taught us about democracy and that majority rules.' I cried, then I went back to the meeting." David Dawley '63

The author, who works for the CollegeNews Service, is former State Editor for The Baltimore News American. Profes-sionally, she writes under the name Ham-mel, but around Hanover she is known asLaura Dicovitsky.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureSTRATS

April 1986 By Willem Lange -

Feature

FeatureRecent Accessions in European and Graphic Art at The Hood

April 1986 By Hilliard T. Goldfarb -

Article

Article"Kiki" McCanna: Steward of Sanborn

April 1986 By Lee McDavid -

Article

ArticleRave Reviews?

April 1986 By Dorothy L. Foley '86 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1959

April 1986 By Richard A. Masterson -

Class Notes

Class Notes1979

April 1986 By Philip B. Gray