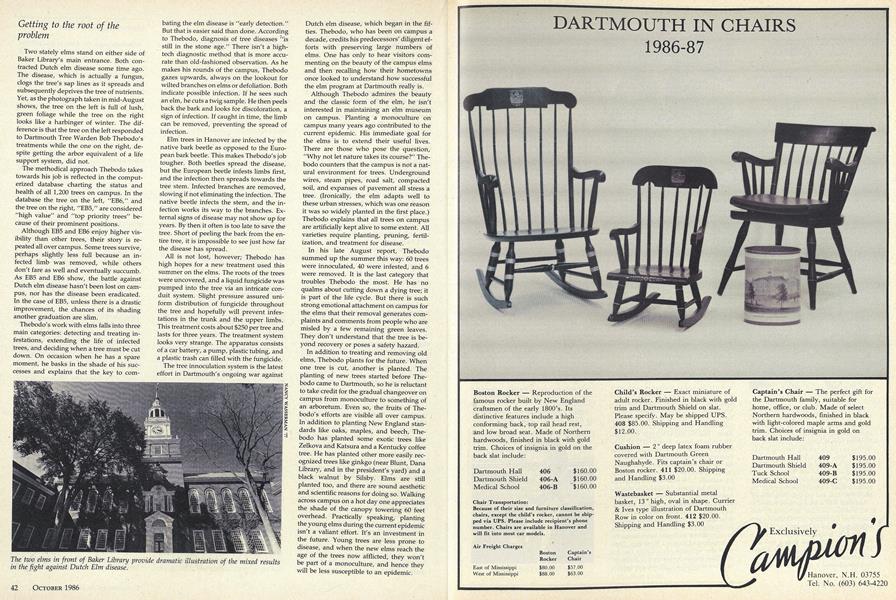

Two stately elms stand on either side of Baker Library's main entrance. Both contracted Dutch elm disease some time ago. The disease, which is actually a fungus, clogs the tree's sap lines as it spreads and subsequently deprives the tree of nutrients. Yet, as the photograph taken in mid-August shows, the tree on the left is full of lush, green foliage while the tree on the right looks like a harbinger of winter. The difference is that the tree on the left responded to Dartmouth Tree Warden Bob Thebodo's treatments while the one on the right, despite getting the arbor equivalent of a life support system, did not.

The methodical approach Thebodo takes towards his job is reflected in the computerized database charting the status and health of all 1,200 trees on campus. In the database the tree on the left, "EB6," and the tree on the right, "EB5," are considered "high value" and "top priority trees" because of their prominent positions.

Although EB5 and EB6 enjoy higher visibility than other trees, their story is repeated all over campus. Some trees survive, perhaps slightly less full because an infected limb was removed, while others don't fare as well and eventually succumb. As EB5 and EB6 show, the battle against Dutch elm disease hasn't been lost on campus, nor has the disease been eradicated. In the case of EB5, unless there is a drastic improvement, the chances of its shading another graduation are slim.

Thebodo's work with elms falls into three main categories: detecting and treating infestations, extending the life of infected trees, and deciding when a tree must be cut down. On occasion when he has a spare moment, he basks in the shade of his successes and explains that the key to combating the elm disease is "early detection." But that is easier said than done. According to Thebodo, diagnosis of tree diseases "is still in the stone age." There isn't a hightech diagnostic method that is more accuate than old-fashioned observation. As he makes his rounds of the campus, Thebodo gazes upwards, always on the lookout for wilted branches on elms or defoliation. Both indicate possible infection. If he sees such an elm, he cuts a twig sample. He then peels back the bark and looks for discoloration, a sign of infection. If caught in time, the limb can be removed, preventing the spread of infection.

Elm trees in Hanover are infected by the native bark beetle as opposed to the European bark beetle. This makes Thebodo's job tougher. Both beetles spread the disease, but the European beetle infests limbs first, and the infection then spreads towards the tree stem. Infected branches are removed, slowing if not eliminating the infection. The native beetle infects the stem, and the infection works its way to the branches. External signs of disease may not show up for years. By then it often is too late to save the tree. Short of peeling the bark from the entire tree, it is impossible to see just how far the disease has spread.

All is not lost, however; Thebodo has high hopes for a new treatment used this summer on the elms. The roots of the trees were uncovered, and a liquid fungicide was pumped into the tree via an intricate conduit system. Slight pressure assured uniform distribution of fungicide throughout the tree and hopefully will prevent infestations in the trunk and the upper limbs. This treatment costs about $250 per tree and lasts for three years. The treatment system looks very strange. The apparatus consists of a car battery, a pump, plastic tubing, and a plastic trash can filled with the fungicide.

The tree innoculation system is the latest effort in Dartmouth's ongoing war against Dutch elm disease, which began in the fifties. Thebodo, who has been on campus a decade, credits his predecessors' diligent efforts with preserving large numbers of elms. One has only to hear visitors commenting on the beauty of the campus elms and then recalling how their hometowns once looked to understand how successful the elm program at Dartmouth really is.

Although Thebodo admires the beauty and the classic form of the elm, he isn't interested in maintaining an elm museum on campus. Planting a monoculture on campus many years ago contributed to the current epidemic. His immediate goal for the elms is to extend their useful lives. There are those who pose the question, "Why not let nature takes its course?" Thebodo counters that the campus is not a natural environment for trees. Underground wires, steam pipes, road salt, compacted soil, and expanses of pavement all stress a tree. (Ironically, the elm adapts well to these urban stresses, which was one reason it was so widely planted in the first place.) Thebodo explains that all trees on campus are artificially kept alive to some extent. All varieties require planting, pruning, fertilization, and treatment for disease.

In his late August report, Thebodo summed up the summer this way: 60 trees were innoculated, 40 were infested, and 6 were removed. It is the last category that troubles Thebodo the most. He has no qualms about cutting down a dying tree; it is part of the life cycle. But there is such strong emotional attachment on campus for the elms that their removal generates complaints and comments from people who are misled by a few remaining green leaves. They don't understand that the tree is beyond recovery or poses a safety hazard.

In addition to treating and removing old elms, Thebodo plants for the future. When one tree is cut, another is planted. The planting of new trees started before The bodo came to Dartmouth, so he is reluctant to take credit for the gradual changeover on campus from monoculture to something of an arboretum. Even so, the fruits of The bodo's s efforts are visible all over campus. In addition to planting New England standards like oaks, maples, and beech, The bodo has planted some exotic trees like Zelkova and Katsura and a Kentucky coffee tree. He has planted other more easily recognized trees like ginkgo (near Blunt, Dana Library, and in the president's yard) and a black walnut by Silsby. Elms are still planted too, and there are sound aesthetic and scientific reasons for doing so. Walking across campus on a hot day one appreciates the shade of the canopy towering 60 feet overhead. Practically speaking, planting the young elms during the current epidemic isn' t a valiant effort. It's an investment in the future. Young trees are less prone to disease, and when the new elms reach the age of the trees now afflicted, they won't be part of a monoculture, and hence they will be less susceptible to an epidemic.

The two elms in front of Baker Library provide dramatic illustration of the mixed resultsin the fight against Dutch Elm disease.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureBONFIRE!

October 1986 By Shelby Grantham -

Feature

FeaturePapa's Son

October 1986 By Everett Wood '38 -

Feature

FeatureA China Perspective

October 1986 By President David T. McLaughlin '54 -

Article

ArticleDartmouth Authors

October 1986 By C. E. Widmayer -

Article

ArticleCarl Thum: Teacher of how to learn

October 1986 By Georgia Croft -

Sports

SportsThe Key to Defense

October 1986 By Jim Neeciham '70