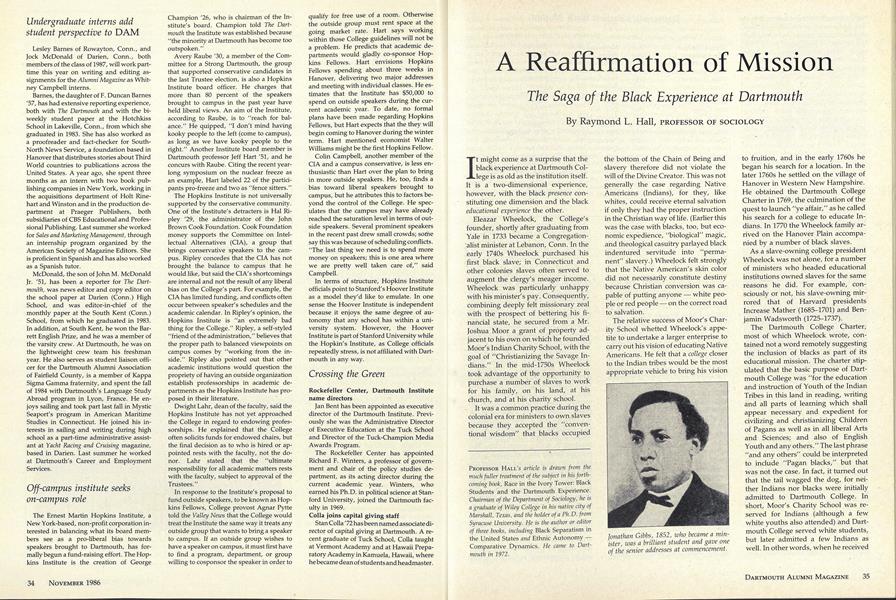

The Saga of the Black Experience at Dartmouth

It might come as a surprise that the black experience at Dartmouth College is as.old as the institution itself. It is a two-dimensional experience, however, with the black presence constituting one dimension and the black educational experience the other.

Eleazar Wheelock, the College's founder, shortly after graduating from Yale in 1733 became a Congregationalist minister at Lebanon, Conn. In the early 1740s Wheelock purchased his first black slave; in Connecticut and other colonies slaves often served to augment the clergy's meager income. Wheelock was particularly unhappy with his minister's pay. Consequently, combining deeply felt missionary zeal with the prospect of bettering his financial state, he secured from a Mr. Joshua Moor a grant of property adjacent to his own on which he founded Moor's Indian Charity School, with the goal of "Christianizing the Savage Indians." In the mid-1750s Wheelock took advantage of the opportunity to purchase a number of slaves to work for his family, on his land, at his church, and at his charity school.

It was a common practice during the colonial era for ministers to own slaves because they accepted the "conventional wisdom" that blacks occupied the bottom of the Chain of Being and slavery therefore did not violate the will of the Divine Creator. This was not generally the case regarding Native Americans (Indians), for they, like whites, could receive eternal salvation if only they had the proper instruction in the Christian way of life. (Earlier this was the case with blacks, too, but economic expedience, "biological" magic, and theological casuitry parlayed black indentured servitude into "permanent" slavery.) Wheejock felt strongly that the Native American's skin color did not necessarily constitute destiny because Christian conversion was capable of putting anyone white people or red people on the correct road to salvation.

The relative success of Moor's Charity School whetted Wheelock's appetite to undertake a larger enterprise to carry out his vision of educating Native Americans. He felt that a college closer to the Indian tribes would be the most appropriate vehicle to bring his vision to fruition, and in the early 1760s he began his search for a location. In the later 1760s he settled on the village of Hanover in Western New Hampshire. He obtained the Dartmouth College Charter in 1769, the culmination of the quest to launch "ye affair," as he called his search for a college to educate Indians. In 1770 the Wheelock family arrived on the Hanover Plain accompanied by a number of black slaves.

As a slave-owning college president Wheelock was not alone, for a number of ministers who headed educational institutions owned slaves for the same reasons he did. For example, consciously or not/his slave-owning mirrored that of Harvard presidents Increase Mather (1685-1701) and Benjamin Wadsworth (1725-1737).

The Dartmouth College Charter, most of which Wheelock wrote, contained not a word remotely suggesting the inclusion of blacks as part of its educational mission. The charter stipulated that the basic purpose of Dartmouth College was "for the education and instruction of Youth of the Indian Tribes in this land in reading, writing and all parts of learning which shall appear necessary and expedient for civilizing and christianizing Children of Pagans as well as in all liberal Arts and Sciences; and also of English Youth and any others." The last phrase "and any others" could be interpreted to include "Pagan blacks," but that was not the case. In fact, it turned out that the tail wagged the dog, for neither Indians nor blacks were initially admitted to Dartmouth College. In short, Moor's Charity School was reserved for Indians (although a few white youths also attended) and Dartmouth College served white students, but later admitted a few Indians as well. In other words, when he received the Dartmouth College Charter, Wheelock had soured on educating Indians as missionaries, preferring instead that the College, as Jere Daniell put it, "eduate white missionaries and have them work either independently or with educated Indians."

The initial presence of blacks as slaves, ironically, laid the foundation upon which the black educational experience at Dartmouth College and elsewhere was built. While owning slaves, Eleazar Wheelock in 1770 admitted and himself educated Caleb Watts, a mulatto, at Moor's Charity School. In 1776 he urged Watts to go to the South "to dissuade the slaves against rebellion." Watts did leave Hanover in that year and was never heard of again. After the Revolutionary War, in the North generally and in New England particularly, a real sense of drift toward blacks set in on the part of members of the American educational establishment. They certainly held contradictory opinions about black equality, but the intellectual structures in which those opinions were held did not appear to be terribly rigid, rigorous, or even well thought out. Their opinions of and action towards blacks seemed to be more the product of habit that went unchallenged. For example, at the founding of the College, Wheelock could own slaves, speak about but not actually grant them their freedom, educate Caleb Watts, and, at the same time, feel that free blacks should urge black slaves to be docile. Wheelock's posture on the race issue carried over to his son John, who in 1807 admitted Prince Saunders to Moor's Charity School but denied Saunders' application for admission to Dartmouth College. In an act analogous to his father's earlier one, John Wheelock urged Saunders to go to Boston to aid black education in that city. Saunders followed his advice.

The sense of drift on the part of the Dartmouth trustees when John Wheelock rejected Saunders' application for admission was not much different when Edward Mitchell, a black from Martinique, West Indies, applied for admission to Dartmouth in 1824. The trustees denied his request for admission. Again, their denial, in all likelihood, reflected tradition and, more importantly, habit. However, in this instance, the students at the College presented the trustees with a petition supporting Mitchell's admission. Thus when the students strongly expressed their support of Mitchell's application, the trustees felt that admitting him was an acceptable thing to do, and no strong opposition on the board was manifested.

But 1824 was a different time and, in a sense, a different era. Perhaps the students knew that Edward Jones had been admitted to Amherst College in 1822 and John Browne Russwurm to Bowdoin in 1824. They also probably knew that Theodore S. Wright matriculated at Princeton Theological Seminary about the same time. It is unlikely that they had any inkling that Alexander Lucious Twilight, a mulatto who passed for white, was graduated from Middlebury College in 1823. In the unlikely event that the students were unaware of these events at other colleges, they were not ignorant of the abolitionist movement that played a prominent role in ending slavery throughout the North by the end of the 1820s. It would seem strange if so selective a group were ignorant of that issue.

Many of the . students in college at the time Mitchell was admitted later became deeply involved in the abolitionist movement. As a number of them would become ministers, missionaries, and teachers, it seemed nat- ural that they would be aware of the social currents of the time, and the race/slavery issue was one of the most volatile. Thus, their petition requesting (not demanding) Mitchell's admission was clear in its support of egalitarian ideals contained in the Constitution: it was unequivocal, wellreasoned, and widely supported. The trustees had never faced the intensity of conviction about a racial issue contained in the students' petition, and certainly not the direct expression of individual and group sentiment in the students' testimonies of support of Mitchell's admission. The trustees undoubtedly were impressed with this show of support, as demonstrated in the reversal of their decision.

The colleges that first accepted blacks Middlebury, Amherst, Bowdoin, and Dartmouth followed a pattern if not a policy of admitting a black student every three or four yearsThis pattern of limited black enrollment in these prestigious colleges, especially those that later constituted the Ivy League, was not merely a characteristic of their pioneering spirit in the 1820s; the same pattern of limited admissions in reality exists today. The policy of limited black admission in the early 1920s was premised on earlier notions of racial inferiority and superiority, making it even more, remarkable that any white college even in the 1820s would have dared to accept a black student, after almost two centuries of black exclusion from higher education. But they did.

A statement of the black educational experience from colonial time towards the middle of the antebellum period can be summarized as follows. When colleges were first established in the American colonies during the 17th century, blacks were excluded. This situation did not change for the remainder of the colonial era. When the colonies threw off the yoke of British domination, blacks still were excluded from American institutions of higher learning. They would continue to be excluded long after the American Revolution, for it was roughly another halfcentury, during the decade of the 1820s, that the historical records show Afro-Americans first being admitted to and graduated from American colleges. When Edward Mitchell graduated from Dartmouth in 1828, he became only the fourth black (counting Middlebury's Twilight) to graduate from an American college. Thus, the college was a vanguard institution in the education of blacks in the United States.

As stated earlier, the few institutions that admitted blacks in the 1820s increased only slightly from that decade until the post-Civil War Reconstruction era, when viable black colleges significantly increased black educational opportunities. The additional white institutions that admitted blacks many of which lasted for only a short time continued the pattern of admitting one or two blacks intermittently. Oberlin College was one of the outstanding colleges that admitted blacks and women in the mid 1830s, with blacks constituting 4 to 5 percent of its small student body between 1840 and 1860. However, most northern colleges continued their policies of black exclusion, as evidenced by one estimate that up to 1840 only about 15 blacks were admitted to northern colleges. By 1865 the number of blacks who had graduated from American institutions of higher learning numbered between 25 and 30, and these were not graduated from Williams, Wesleyan, Brown, Princeton, Harvard, Cornell, and Pennsylvania, to name a few wellknown institutions in the Northeast. While black exclusion from American colleges and universities was the rule, the limited few who were accepted were part and parcel of the "Talented Tenth." Dartmouth was no exception in admitting men from this category.

Interestingly, blacks who attended Dartmouth after Mitchell and prior to the Reconstruction did so under the presidency of Nathan Lord, who served as president for 35 years. Lord s long tenure is particularly important for two reasons: first, his presidency spanned the heated period of national racial and intersectional conflict; second, he initially was a staunch abolitionist (he had been a trustee since 1818 and probably strongly supported Mitchell's admission in 1824), and later in the latter 1840s and even more in the 1850s he became a strong and outspoken pro-slavery advocate.

His pro-slavery activity, however, did not prevent him from supporting individual blacks as evidenced by his aid to runaway slaves who passed through Hanover's station on the "underground railroad" to Canada. More important for our purpose here, while his anti-slavery beliefs led him actively to advocate egalitarian treatment of blacks as a group, the transformation of his beliefs to pro-slavery did not diminish his strong support for individual blacks.

President Lord resigned in 1863 because he and the trustees clashed over the conferring of an honorary degree on Abraham Lincoln. Lord was opposed to President Lincoln's position on the slave issue. In the light of Lord's "support/oppose" stance, consider the following individuals admitted to Dartmouth under his administration.

Thomas Paul

The second black admitted to the College, at the age of 26, was Thomas Paul Jr. He, along with John Russwurm, who was admitted to Bowdoin in 1824, was one of the teachers at the Smith School in Boston, founded by Prince Saunders who, as we have seen was rejected by John Wheelock for admission to Dartmouth and urged instead to go to Boston to aid black education. Paul's was one of the wellknown black abolitionist families in New England, and he sought admission to Dartmouth because of President Lord's reputation as an abolitionist. He had good reason to have faith in Lord's reputation, for in 1835 President Lord had encouraged the establishment of an abolitionist society on campus. When admitted in 1838, Paul became a member of that society which numbered about 150 students. Conforming to his family's abolitionist sentiments and the strong abolitionist contingent at the College, Paul was one of the more passionate and articulate members of the society. In fact, while still a student at the College, he had the signal distinction of adderessing the Massachusetts Anti-slavery Society in Boston in January 1841, a speech which was reprinted in full in the February 19, 1841 issue of William Lloyd Garrison's The Liberator. It was a powerful and poignant speech, one that surpassed, or at least matched, the best abolitionist speeches of the day. The following excerpt from Paul's speech addressed the question of what the abolitionists were attempting to prove:

Why, that a man is a man, and that he is the only human possessor of himself. But these propositions are self-evident; and self-evident propositions, we all know, though the most difficult to be proved, are the most easily understood, because they need no proof. The mind sees their truth intuitively, without the aid of reasoning. The attempt to prove them, therefore, would be ridiculous, were it not for the consideration of the amazing state of delusion and vassalage to which prejudice reduces the mind when unenlightened by reason.

Toward the end of his speech, Paul indicated his awareness that the same abolitionist arguments had perhaps been repeated a thousand times over by other abolitionists. Nevertheless, he argued, new truths must be often repeated and illustrated in a thousand different ways precisely because of "the difficulty of proving self-evident propositions when obscured by prejudice and preconceived opinions."

The next black to be admitted to Dartmouth, although he was not so regarded while at the College, was Pelleman Williams, 1845, of Springfield, Mass. He attended college only one year, 1841-42, and later became one of the leading Reconstruction educators in Louisiana. In the 1860s and 1870s he taught at Straight College, which later became Dillard University.

Augustus Washington

Augustus Washington, 1847, was the second black admitted in Lord's administration. The son of an ex-slave and an Asian mother, he was born in Trenton, N.J. While growing into manhood he became a true believer in the abolitionist cause, because of his father's deep involvement. His admiration for the redoubtable William Lloyd Garrison in the anti-slavery crusade was also influential. Washington pursued his education and interest in photography as well. After completing his educational course he moved to Brooklyn, N. Y., where he taught for a while. Meanwhile, the siren call of photography became stronger than his interest in education; he moved to Hartford, Connecticut to pursue that profession and opened a daguerreotype studio to help finance the continuation of his education, first at Kimball Union Academy. After a short time at KUA, he was accepted at Dartmouth, where he matriculated in 1843 and remained only one year.

Still uncertain about his career, he returned to Hartford, where he earned the reputation of being one of the outstanding daguerreotype photographers of his day. Washington's success as a photographer, however, did not allay his latent concern for the plight of black slaves. With the passage of the Compromise of 1850 and in the wake of steady deterioration of hope among blacks (and some white abolitionists) that they would ever be able to live in equality in the United States, he became increasingly confused and disaffected by the unfolding drama in the United States. Anticipating that the drama would end not to his liking, he agreed with those who felt that African emigration was the only viable alternative. Leaving behind his hardearned reputation as a photographer, Washington left the United States for Liberia "believing that only Africa could be the black man's home in this world. In Liberia, he worked as a school teacher, a daguerreotypist, farmer, and store proprietor."

Jonathan Gibbs

After Augustus Washington's departure in 1844, President Lord converted to the pro-slavery persuasion sometime in 1847. However, less than a year later he admitted another powerfully articulate abolitionist black student, Jonathan Gibbs Jr., no doubt one of the most accomplished men ever to graduate from Dartmouth College. Born in Philadelphia to a Baptist mother and a Methodist father, perhaps wanting to offend neither, Gibbs became a Presbyterian minister. Following on the heels of Augustus Washington, Gibbs prepared for college at Kimball Union Academy. Rejected for admission by at least three other colleges, he entered Dartmouth in 1848. He culminated his brilliant academic career at the College by being chosen to give one of the commencement addresses, ostensibly the second black to do so, following John Russwurm's 1826 commencement speech at Bowdoin. While at the College Gibbs was deeply involved in the abolitionist movement, numbering among his friends the leading abolitionists of his day Frederick Douglass, William Still, William Lloyd Garrison, Charles Sumner, William Wells Brown, and Stephen Smith.

After graduating from Dartmouth in 1852, Gibbs immediately entered Princeton Theological Seminary where he completed his course of study in 1855. In that same year he assumed the pastorate of the Liberty Street Presbyterian Church in Troy, N.Y. Knowing Lord's sentiments on the slavery issue, Gibbs nevertheless "begged Dr. Lord as a special favor to preach his ordination sermon, giving as a reason that his college was the only one which would endure his presence. Few members of the Presbytery were willing to attend the ordination; one of them, a flaming anti-slavery champion, attended but slipped into a back seat and took no part. Owing to the dearth of brother ministers, Dr. Lord was obliged to make the installing prayer as well as to preach."

Gibbs later combined the ministry with politics, moving to Florida, where in 1867 he was appointed the only black Secretary of the State in the Reconstruction South and the first black cabinet member in that state's history. That landmark appointment was followed by another as Superintendent of Public Instruction for the State of Florida in 1873. He died suddenly one year later of a mysterious and suspicious cause. It was rumored that he was poisoned.

Edward Garrison Draper

Born in Baltimore, Md., in 1834, the son of a successful businessman, Edward Draper grew up during the most explosive period of the slavery argument. His father was very much concerned with and involved in the abolitionist movement. Baltimore specifically and Maryland in general did not provide the best setting in which a young black person could pursue a good education. Instead, Edward was sent to Philadelphia separate schools for blacks had been established there since 1822 where he completed secondary school in 1851 and was admitted to Dartmouth in the same year. He was graduated from the College in 1855. After Dartmouth, he emigrated to Liberia where he practiced law. Shortly after their arrival, the Drapers contracted fever, a fate that befell a host of emigrants to Liberia. Many, in fact, perished because their constitutions could not successfully cope with the African viruses. The Drapers fought off this initial bout with fever, but Edward, unfortunately, was not able to overcome a different kind of illness. On December 8,1858, a little over a year after arriving in Liberia, he died of tuberculosis, two weeks prior to his 25th birthday. Thus ended the life of Dartmouth College's fourth black graduate.

The biographical sketches above are but a few examples of the many outstanding individuals who attended the College. All of them receive fuller treatment in the more detailed study I am now completing. Included in that study are others who should be more briefly mentioned here to give a reader the flavor of their character and accomplishments. Louis Charles Roudanez was born to a free black woman and a French merchant mariner in Louisiana. After attending school in New Orleans, he received his medical degree from the University of Paris in 1853. In that same year, because of the steadily deteriorating state of race relations in Louisiana shortly after the Compromise of 1850, it was inexpedient for him to return to New Orleans. Instead, he entered Dartmouth Medical College, where he received another medical degree in 1857. He then returned to New Orleans to practice medicine, and also to engage in politics. He founded and published, at his own expense, a daily newspaper. His was thefirst black daily in the nation. Two of his sons attended Dartmouth Medical School in 1890, becoming Dartmouth's first black legacy.

John Randall Blackburn, the son of a white farmer and black mother, entered Dartmouth in 1859 and departed at the outbreak of the Civil War. He became one of Ohio's outstanding educators, serving as a trustee at (black) Wilberforce and (white) Ohio University. ]He was the first black to receive an honorary degree from Dartmouth; that event occurred in 1883. Blackburn was the last antebellum black to attend Dartmouth.

Spanning the last decade of the 19th century and the first of the 20th, it was under the administration of William Jewett Tucker that the percentage of black students rose significantly. During his 16 years in office 22 black students were admitted. In contrast, during President Asa Dodge Smith's 14-year administration, from 1863 to 1877, only three black students were admitted, an average of one every 4.7 years; in President Samuel Colcord Bartlett's 15 years in office, from 1877 to 1892, four black students were admitted, an average of one every 3.8 years. Thus, Tucker's presidency brought significant change in black enrollment. In addition, Tucker's administration and his emphasis on a "new" Dartmouth propelled the College into becoming a national institution. It was Tucker who conferred an honorary LL.D. upon Booker T. Washington in 1901. Matthew Bullock was the first black Dartmouth football player to receive Ail-American honorable mention. And Ernest Just, one of the nation's most eminent marine biologists, graduated in the class of 1907.

During the Nichols and Hopkins years, from 1909 to 1945, the College continued to admit outstanding black students, many of whom achieved nat ional prominence. As examples, Lester Granger 'l8 was head of the National Urban League; Dr. CharlesDavis '39 was Professor of English and founder of the Afro-American Studies Program at Yale; and Charles Duncan'45 headed Howard University's Law School. Interestingly, during the Nichols/Hopkins years a disproportionate number of black Dartmouth graduates pursued medical careers.

John Sloan Dickey became twelfth in the Wheelock Succession in 1945. Profound changes occurred at the College during his 24-year tenure; some stemmed from a combination of both external and internal events and developments, while others resulted from his deliberate efforts to produce specific kinds of change. In his third year as president, Dickey stated that he opposed the fraternity discrimination based on race and religion that national headquarters forced on Dartmouth men. After years of debate, the students held a referendum on the issue in the early 19505. It was inconclusive. Another was held in 1953-54 and this time an agreement was reached. Led by David T. McLaughlin '54, president of the Undergraduate Council, it was stipulated that fraternities affiliated with nationals with discriminatory clauses must disaffiliate and "go local" by 1960 or lose official recognition. It proved to be largely effective, although some fraternities that disaffiliated from their nationals continued to discriminate locally. In spite of losing a few battles, President Dickey won the war against fraternity discrimination.

The Tucker Foundation, established in 1953 but not a functioning reality until the late 19505, was another Dickey initiative. Like President Tucker, President Dickey believed that education without moral and ethical principles left a large spiritual void. His hope was that the Tucker Foundation would serve the spiritual needs of Dartmouth men and encourage them to make judgments on the basis of an individual's character as opposed to following stereotypic notions based on skin color.

Another important change initiated by President Dickey was the Great Issues Course. Having spent much of his time in the State Department, he was very much aware of the profound changes taking place in the world at large and in American society in particular. He felt, therefore, that Dartmouth men, in order to be really liberally educated, should be aware of these developments, and should be exposed to the individuals involved in the changes taking place at home and abroad.

During the Dickey administration these three developments, among a number of others, laid the foundation for definite change for the better in the black experience at Dartmouth. The struggle over fraternity discrimination made it possible for blacks to become more deeply involved in the life of the College, since fraternities were then at the center of campus social life. Even if they were invited to do so, and not many were, blacks did not exactly excuse the pun rush to join the fraternities. A few did, however. The is sue of fraternity discrimination heightened the awareness Dartmouth men had of the issue of race at the College and in the society at large.

The Great Issues Course brought to Hanover blacks, both African and Afro-Americans, who were on the cutting edge of change. Walter White, Thurgood Marshall, C. Eric Lincoln, Ralph Ellison, Martin Luther King Jr., and a number of other blacks came to Dartmouth as leaders and as Great Issues lecturers.

The Tucker Foundation, first headed by Professor Fred Berthold '45, and later by Richard Unsworth, Charles Dey '52, and Warner Traynham '58 (and now by James Breeden '57), kept before the Dartmouth community thought-provoking ethical, moral, and spiritual issues and problems. It also played a key role in prompting the College's involvement in the civil rights movement.

The Civil Rights Movement

In an interview with Leonard M. Rieser '44 (now Director of the John Sloan Dickey Endowment for International Understanding), then Dean of the Faculty and Provost of the College, regarding the impact of the civil rights movement at Dartmouth, his first response was, "The civil rights movement came to Hanover late." He was correct. Following the 1954 Supreme Court decision, when Rosa Parks refused to give up her seat to a white man in Montgomery, Alabama in 1955, that act triggered what was to become what Senior Fellow Don T. O'Bannon '79 called the "Decisive Decade." The southern phase of the activist civil rights movement, led by Martin Luther King Jr. and a host of other local leaders, was off and running.

It was only in the latter 1950s and early 1960s that the civil rights movement became national, and it was only towards the mid-1960s that its echoes faintly reached Hanover. It was well towards the latter sixties that its full impact was felt by the Dartmouth community in Hanover. A few individuals at Dartmouth, both black and white, involved themselves in the movement prior to the mid-sixties. A few went South to participate in programs sponsored by the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) and other organizationally sponsored voter registration drives, demonstrations, and literacy programs.

However, the period between the mid-sixties and 1970 witnessed the greatest change at Dartmouth. First, in the early sixties black student enrollment, prompted by the Negro Application Encouragement Program, increased black applicants and matricul ants beginning in 1964, and these students tended to model their behavior on and follow the ideas of the militant wing of the civil rights movement Malcolm X, Stokeley Carmichael, Amiri Baraka, the Black Panther Party, the Nation of Islam, and the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE). The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) and the Urban League, as examples of the integrationist wing of the civil rights movement, received less than passing attention from the black students. Many of the "militants" mentioned above actually came to speak at the College.

Despite the nationalization of the civil rights movement and the activity it generated at Dartmouth, as late as 1967 one important ingredient was still missing a formal organization of black students. Such organizations had existed at many other institutions Columbia and Harvard as examples since 1963. In the spring of 1967, however, the Afro-American Society was organized at Dartmouth, and it continues to function today. In 1981, Jandel T. Allen 'BO (now Dr. Jandel T. Allen Davis) was elected Afro-American chairwoman, the only female to head the Society.

The escalation of civil rights activity in the nation, once it reached Hanover, in the short and long term generated generally positive results. In 1964, for example, A Better Chance (ABC) Program was founded at Dartmouth. Its purpose was to extricate bright minority students from inner-city schools in order that they spend their junior and senior years at better non-inner-city high schools. In 1967, the Foundation Years Program, emanating out of Chicago, was established at Dartmouth to enable bright black gang members to redirect their "smarts" into academic channels. Later, the structured Freshman Year and the Bridge Programs were instituted at the College to aid the academic development of minority students. As at most other white institutions, the Black Studies Program was established in the late 19605. In addition, an equal opportunity committee was established.

The event that had a profound impact on Dartmouth, and most other American, institutions as well, took place in Memphis, Tenn., on April 4, 1968. The murder of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. caused Wallace Ford '70 to take to the air on WDCR and declare war on White America. While his call for war was not heeded, the institution did launch a search for an appropriate response to this dastardly act on America's Black Prince of Peace. The trustees established a committee comprised of faculty, administrators, and a community leader to study and make recommendations as to the proper response the College should make to continue the work begun by Dr. King. A number of recommendations were offered, but the most important, following the lead of other institutions, was to increase the size of the black student body at the College. Thus, a guideline was established to the effect that about 10 percent of each entering class should be black or minority students. The class of 1973 included 81 blacks, an improvement on the much smaller number in all prior years.

The presidency of John Kemeny continued efforts to enhance the minority experience at the College. In 1972 women were first admitted to the College; and in his administration the number of Native American students was increased, finally fulfilling the College's original Charter.

As black enrollment increased in the late sixties, so did the number of black students who have matched the preachievements of their 19th century counterparts. Michael Robinson Hollis '75, for example, is the founder, chairman of the board, and chief executive officer of Air Atlanta in his hometown. While at the College, Michael was, in addition to a number of other things, Assistant to President Kemeny and a Senior Fellow. Mark E.Brown 'Bl, now an attorney in San Francisco, was also assistant to President Kemeny and a Senior Fellow. Chris Cannon 'Bl was the first black president of the UGC; he now practices law in Chicago. Angela Arrington '79 has made remarkable strides in the field of psychology. Riki L. Fairley '78. the daughter of Richard L. Fairley '55, has achieved remarkable success in marketing. And the list goes on.

By the end of the Kemeny presidency, the African and Afro-American Studies Program had been enhanced, the Women's Studies Program had been established, a Native American Studies program was in place, and minority students (black and Native Americans), women and North Country poor whites were present in the Dartmouth community in greater numbers.

In a chapter entitled, "An Epilogue to a Prologue or Towards the Reinvention of the Dartmouth Family," because my data end with the Kemeny Administration, I make a few remarks regarding events and developments in the McLaughlin administration. It is, of course, much too early to make any definitive statements or draw any sensible conclusions while history is in the making. But it is not too soon to say that with the appearance of the Review issues of race, gender, and class, to name a few, again took center stage in the continuing saga of race at Dartmouth. The ironic result of this "new" challenge has been an accelerated and more determined examination and reaffirmation of the mission of the College.

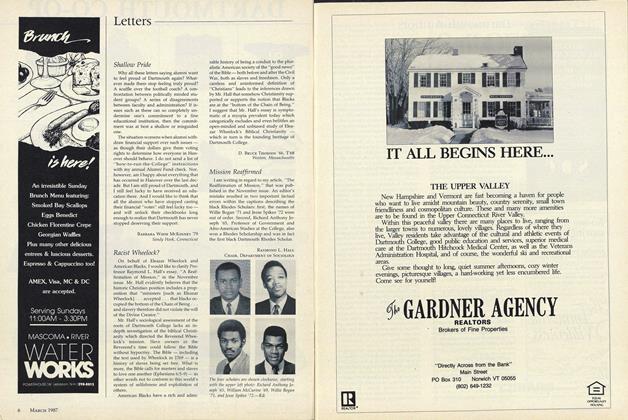

In short, the Dartmouth Community, the Dartmouth Family these metaphors of unity that characterized Dartmouth in the past are deter In the 1970s women began to take their■place among outstanding students. Fromthe top, Eileen Cave '76, who did graduateworork in print-making and is now an exhibiting artist; Angela Arrington '79, an honors scholar who is now a clinical psychologist; Jandel Allen-Davis 'BO, president of the Afro-American Society and a C& G, who took her M.D. degree at Dartmouth Medical School; and Juanita Sanders, now doing graduate work, who wasdirector of the Gospel Choir, a WDCR discjockey, a Congressional intern, and MissBlack Massachusetts.

mined to become applicable and appropriate characterizations of all Dartmouth women and men, irrespective of race, sex, religion, or national origins. History is on their side. The members of the "old" and "new" Dartmouth are determined to be Voces Clamantes in Deserto. Parate Viam Dominerectas facite semitas ius.

Jonathan Gibbs, 1852, who became a minister, was a brilliant student and gave oneof the senior addresses at commencement.

Among the 20 black students enrolled inthe 1800's were Winfield Montgomery '78(top) and Robert Brown '98. Both came toDartmouth from Virginia.

Ernest Just '07, who took his Ph.D. at Chicago, was one of the country's outstandingmarine biologists.

Matt Bullock '04, one of Dartmouth's football greats, toon All-American honors.

Lester Granger '18 capped his career of distinguished public service as head of the National Urban League.

R. Harcourt Dodds '58, the first black tobe a Dartmouth trustee, held several NewYork City legal posts before becoming a corporate executive.

Three black graduates of Dartmouth who won Rhodes Scholarships: from the left, WilliamMcCurine '69, Willie Bogan '71, and Jesse Spikes '72.

PROFESSOR HALL'S article is drawn from themuch fuller treatment of the subject in his forthcoming book, Race in the Ivory Tower: Black Students and the Dartmouth Experience. Chairman of the Department of Sociology, he isa graduate of Wiley College in his native city ofMarshall, Texas, and the holder of a Ph.D. fromSyracuse University. He is the author or editorof three books, including Black Separatism in the United States and Ethnic Autonomy Comparative Dynamics. He came to Dartmouth in 1972.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

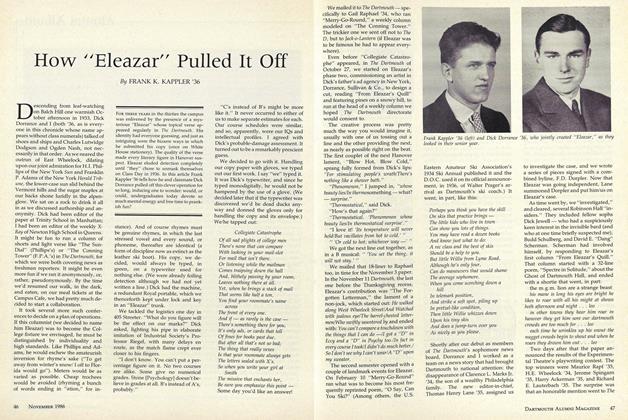

FeatureHow "Eleazar" Pulled It Off

November 1986 By FRANK K. KAPPLER '36 -

Feature

FeatureThe New England Review and Bread Loaf Quarterly

November 1986 By Peter Mandel -

Article

ArticleDartmouth Authors

November 1986 By Bob Monahan '29 -

Article

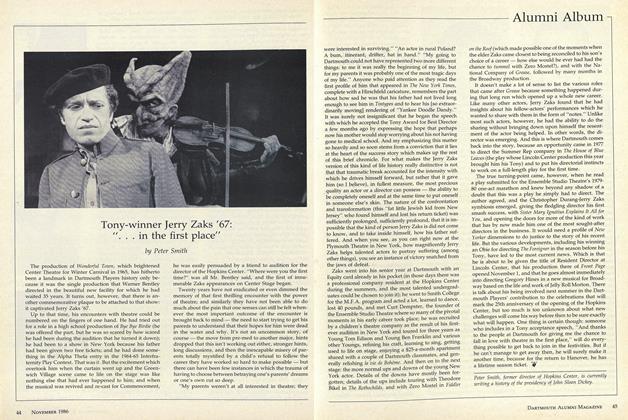

ArticleTony-winner Jerry Zaks '67: "...in the first place"

November 1986 By Peter Smith -

Article

ArticleDavid O. Hooke '84: Chubber's Boswell

November 1986 By Lee Michaelides -

Sports

SportsDartmouth Soccer

November 1986 By Jim Needham '70

Raymond L. Hall

Features

-

Feature

FeatureThe Reunion Week

July 1961 -

Feature

FeatureDays of Controversy: 1816-1819

June 1962 -

Feature

FeatureRETIRING FACULTY

JUNE 1972 -

Feature

FeatureThe Future of Liberal Arts Education at Dartmouth

JUNE 1972 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryHOW TO THROW A REALLY BIG SHOW

Sept/Oct 2001 By ERIC MARTIN '75 -

Cover Story

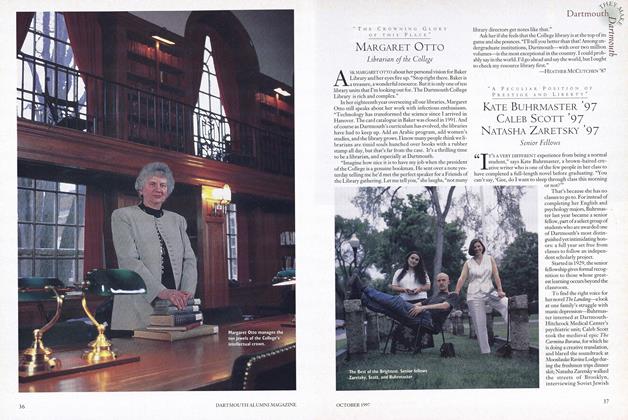

Cover StoryMargaret Otto

OCTOBER 1997 By Heather McCutchen '87