Communists meeting in Rockefeller Center! The American Bar Association hosting a meeting with the Association of Soviet Lawyers during the midst of the Daniloff arrest and detention! How did it come about, and why were Dartmouth College and its Dickey Endowment involved?

The answer is to be found in the interaction of two vital American forces indeed, institutions the law and the liberal arts tradition. These two forces brought 20 members of the Association of Soviet Lawyers (ASL) to Hanover, N.H., in September to meet with 20 American Bar Association (ABA) members for the purpose of learning about and evaluating our respective legal systems. It was in a true sense a historic gathering, the first formal meeting between delegations from the two largest bar associations in the world. It was controversial; indeed, to describe any aspect of it is to invite dispute. For example, even the initial agreement between the two associations generated controversy because the ASL is perceived by some as a mere organ of the Soviet state and not an independent bar association like the ABA. The meeting went forward, however, because communication even, or perhaps especially, among profoundly differing perspectives and philosophies was deemed an important goal in and of itself. That view was well summed up by one of the 10 Dartmouth Russian majors participating, who said, "If lawyers cannot talk who can or should?" The controversial nature of the meeting attracted the attention of groups concerned about Soviet policies and, of course, the media. If the value of a meeting can be gauged by media reaction, then this seminar was productive: the local and national press gave solid and detailed accounts. Even the observers from groups suspicious of such encounters with the Soviets seemed to concede that, if not positively productive, the meetings were more worthwhile than they had expected. In fact, although a group of New England newspaper publishers scheduled to go to the Soviet Union that same week had cancelled their trip because of Daniloff's arrest, several present observed that if they had been jailed in Moscow, as Nick Daniloff was, they .would not necessarily have been heartened by the news that American lawyers and judges cancelled a meeting with Soviet lawyers and judges until their problems were resolved.

What is Dartmouth's interest in all of this? The mission of liberal arts institutions is to communicate information on matters of intellectual and cultural concern. And, certainly relations between the world's two great powers involving as they do issues of war and peace, trade and commerce, human rights, science, environment, and the arts fall in this category. Indeed, the single issue of war and peace clouding as it does, all others made this exchange the business of our college and of its alumni including the 4,000 or more "lawyer alumni."

The Dartmouth participants in this meeting follow in the tradition established by a number of Dartmouth greats George Marsh, Daniel Webster, Rufus Choate, John Sloan Dickey lawyers who have never shied away from controversial issues or ideas, both during and after their college days. Dartmouth is the stronger and more esteemed place because of their actions. They were committed to the view that progress was achieved through the exchange of ideas and the interaction among individuals championing different causes. All of these individuals would be comforted that Dartmouth continues to hold itself forth as a forum for the exchange of ideas, and by the acceptance of academic responsibility reflected in these actions. With the benefit of their sense of history, they would surely counsel patience and caution us that progress comes slowly. Ideals, realistic objectives, and a sense of our colleges' heritage and future were all part of this adventure. But accomplishments are better described in factual ways. It is fitting therefore to share with you some of the small but important parts of that event.

A full year ago and more, in May 1985, the Dartmouth Lawyers Association indicated its commitment to this seminar with a contribution to the Dickey Endowment. That endowment and Dartmouth's commitment exemplified in the yeoman efforts of Dean Leonard Rieser, Head of the Dickey Endowment, helped make the meeting the success that it was.

As readers of this publication will readily understand, Dartmouth its setting and its traditions lent an intangible dimension to the seminar which affected the Soviet delegation as well as their American hosts. As one of the Dartmouth alumni participants, Federal District Court Judge Frank Kaufman '37, observed: "If the granite of New Hampshire can be shaped by the elements, so then certainly the attitudes of the Soviets are not totally impervious to change."

Now for the details. On September 11, 1986, the Soviets arrived via Aeroflot in Montreal, Canada. After the 13-hour flight from Moscow, there was a five-hour bus ride to Hanover for the first reception. Very tired on arrival at the Inn, the Soviets were reassured by the quietness of downtown Hanover. After their first (of several), caucuses, the hardy among them tried their hands, literally, on lobster at a late evening clambake. All went well and the dialogue began.

•Soviet lawyers from Russia, Lithuania, Latvia, and the Ukraine strolling across campus, accompanied by Dartmouth '87s speaking Russian and trying to explain: "It is all our college. It is over 200 years old!" Brand new '90s trickling in to Hanover for the start of their college career, bright and shining, as only frosh can be.

•Federal District Court Judge Matthew Byrne of Los Angeles shows a group of the Soviets Baker Library and the Orozco murals. A Soviet woman lawyer tells him in jest, "I like them apart from the theme."

•Two mock trials, one Soviet, one American, the latter with Russian lawyers and Dartmouth Russian majors as jurors.

The second day ended with the ABA and ASL participants enjoying dinner at the homes of Dartmouth faculty members. Gracious professors and their families entertained Dartmouth students, ABA leaders, and Soviet and American legal professionals. That evening's exchanges were spirited, frank, and illuminating. The faculty members deserve special mention; their involvement and their commitment to uninhibited expression and academic freedom make them a credit to the College.

The windup was a panel session no holds barred. Questions were put to the Soviets not only as to differences in the systems, but about specific cases Orlov and Daniloff (both released two weeks later), Shcharansky, anti-Semitism, political trials, restricted immigration. The Soviets, too, had hard questions for their hosts: do not the guilty often escape? What about crime victims? How adequately are the poor represented? Is the American judiciary truly independent even though judges are appointed by the President?

Not all the answers satisfied, but maybe it is the questions that are important. They may be the beginnings of understanding, and from such understanding can come mutual trust and respect. Without knowledge, it is impossible to know when one agrees or disagrees. It is necessary to understand how wide the chasm is between our legal system with its emphasis on individual rights and freedom and theirs a state system with collective goals and objectives. To bridge differences it is necessary to understand their roots and look for areas where there are common concerns. These are evolving war and peace, trade and commerce, human rights, to name a few.

Out of the meetings came a few observations and maybe a concession or two.

•The Soviets were impressed with the unrehearsed and at times almost extemporaneous quality of the American jury trial and would like more lawyer involvement within their own system.

•The Soviet system may dispense justice well in the routine case, but often does not work at all in the exceptional cases. •Both sides seemed to agree that trial observers, for us in their country and for them here, would be a useful way of furthering dialogue.

•The Soviets, at a fundamental level, seem mystified by the notion of an independent judiciary. In my view, they sense something important about this concept, but find it totally at odds with their own system.

•The discussions highlighted the differences between our adversary system with its emphasis on the process as a way of finding the truth, and their inquisitorial one (like that in effect in many European nations) which downplays the process and focuses on finding out the "objective" truth. To some degree these differences reflect differing objectives as well: our system emphasizes assuring that the innocent are not punished even at the cost of occasionally freeing the guilty; the Soviet system concentrates far more on assuring that the guilty are punished.

The list could go on, and it will as these meetings continue. Another seminar is scheduled for Moscow in May, and again at Dartmouth in September 1987 with many of the same participants. This process is slow and requires much work, but it offers hope that our differences can be understood, if not always bridged.

The seminar concluded with a reception at President McLaughlin's home where the vice president of the Association of Soviet Lawyers, Professor Victor Karpetz, noted Dartmouth's " 'round this girdled earth reputation" and toasted its great lawyer Daniel Webster, who "saved this college from the state a most worthwhile endeavor."

The final dinner took place at the Hanover Inn and was attended by notable array of ABA dignitaries, including past Presidents Janofsky and Falsgraf, President-elect Robert McCrate from New York, and President Eugene Thomas from Boise, Idaho. Participants dined with Dartmouth's faculty and student hosts and translators. Russian was the language of the evening. ABA President Thomas talked of the seminar's potential historic significance as a meeting of professionals who are concerned that law be an effective force in the lives of both the Soviet and American people and of the participants' great responsibility to see that this is accomplished. David McLaughlin and Leonard Rieser gave a sense of Dartmouth's abiding interest in this exchange of knowledge and the dialogue about the important issues of our times.

Where will the dialogue end? In a sense, the best answer is that it will not. The process of exchanging facts, exposing ideas, and developing a basis for trust must go on, and perhaps in 10, 20, or a 100 years, dialogue and hope will replace suspicion and pessimism in our relations with the Soviet Union. I'd settle for that.

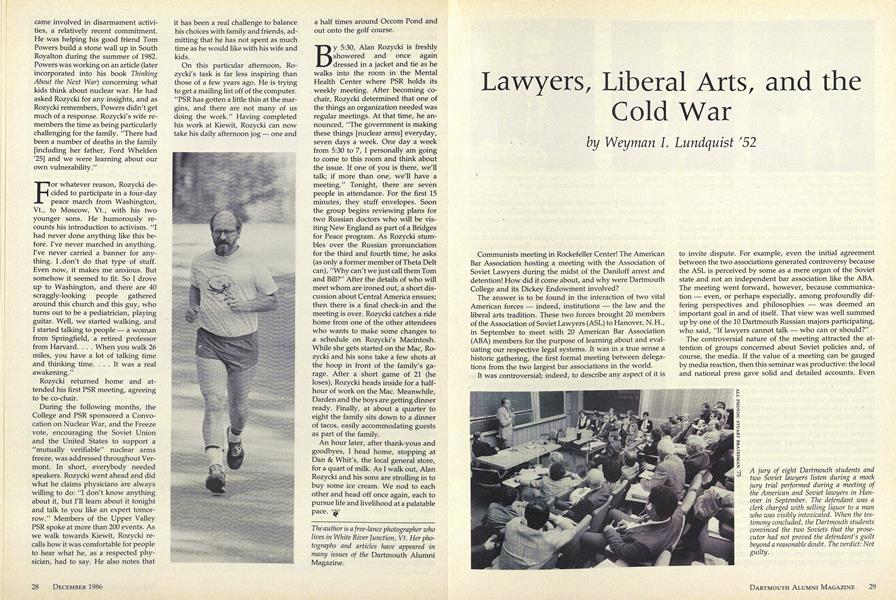

A jury of eight Dartmouth students andtwo Soviet lawyers listen during a mockjury trial performed during a meeting ofthe American and Soviet lawyers in Hanover in September. The defendant was aclerk charged with selling liquor to a manwho was visibly intoxicated. When the testimony concluded, the Dartmouth studentsconvinced the two Soviets that the prosecutor had not proved the defendant's guiltbeyond a reasonable doubt. The verdict: Notguilty.

Igor Karpetz, director of the All-Union Institute of Crime Studies in Moscow andvice president of the ASL.

U.S. District Judge William MatthewByrne of Los Angeles.

Yuri G. Matveyev, dean of the Kiev University Law School.

The participants "toasted" each other and their accomplishments atthe conclusion of the seminar. From left to right: George P. Fletcher,Columbia University Law School professor; Eugene C. Thomas,president of the ABA; and ASL vice president Igor Karpetz.

Trial lawyer Weyman I. Lundquist '52, left, confers with VasiliyA. Vlashihin, senior research fellow at The Institute of U.S. andCanadian Studies in Moscow.

Weyman I. Lundquist is a trial lawyer, practicing in San Francisco.He is chairman of the ABA's steering committee on Soviet dialogue.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

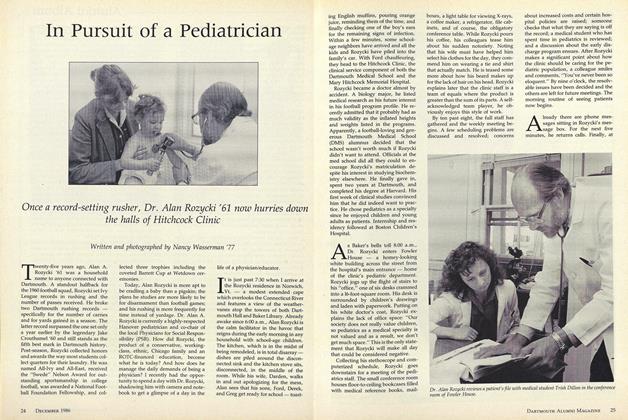

FeatureIn Pursuit of a Pediatrician

December 1986 By Nancy Wasserman '77 -

Feature

FeatureRichard Hovey: The Incomplete Arthurian

December 1986 By Daniel P. Nastali -

Feature

FeatureSnowmaking at the Dartmouth Skiway: Taking the Wonder Out of Winter

December 1986 By Lee Michaelides -

Article

ArticleMarianne Alverson: At home in many worlds

December 1986 By Lee McDavid -

Article

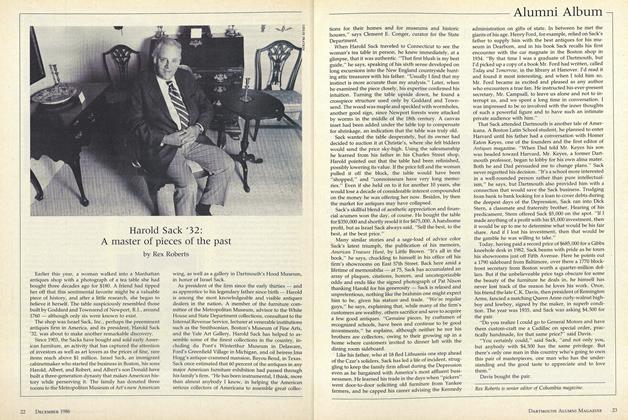

ArticleHarold Sack '32: A master of pieces of the past

December 1986 By Rex Roberts -

Article

ArticleDartmouth Authors

December 1986 By C. E. Widmayer

Features

-

Feature

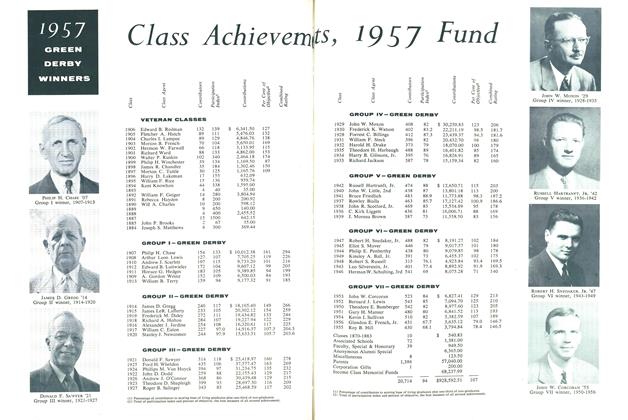

FeatureClass Achievemts, 1957 Fund

December 1957 -

Feature

FeatureSIENNA CRAIG

Sept/Oct 2010 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryLooking for Mr. Goodjob

MAY • 1987 By Jock McDonald '87 -

Feature

FeatureMost Exciting Place on Campus

April 1962 By JOHN R. SCOTFORD JR. '38 -

Feature

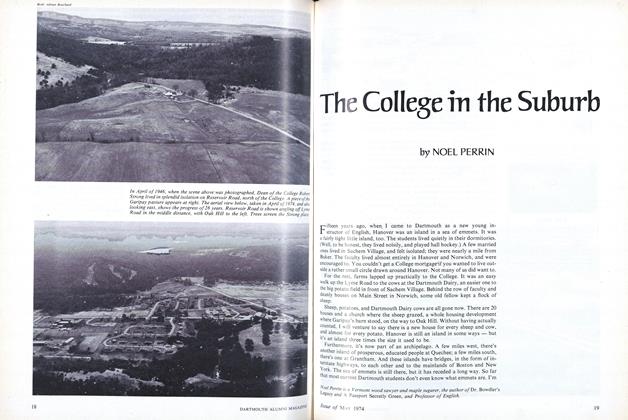

FeatureThe College in the Suburb

May 1974 By NOEL PERRIN -

Feature

FeatureReady to Roll

JANUARY | FEBRUARY 2020 By RICK BEYER ’78