3610 Oriole Drive Columbus, IN 47203

[Two issues ago we began our study of anthropology majors in the class of 1965. We have previously visited with BirgerBenson, Jock Hosmer, Lew Wheaton, BillRust, Bill Herrold, Jeff North, Bill Curtis, and Lynn Mason and are now nearing the conclusion of our effort to answer the question "What would anyone possibly do with that kind of major?"]

Al "Deke" Dekin was a Dartmouth anthropology major who, unlike the others we have met, remained in the field he studied as an undergraduate. Deke went to Michigan State University for his Ph.D. and taught anthropology for seven years at SUNY at Potsdam. In 1975 he became associated with the studies of prehistoric Eskimo culture being conducted by the University of Alaska in advance of the Alaskan pipeline construction. He moved to the faculty of SUNY at Binghamton in 1976 and became chairman of the anthropology department in 1979. In addition to his academic duties in the nationally-recognized department at Binghamton, he also serves as the director of SUNY's Public Archeology Facility. This unique organization was formed to provide contract archaeology fitting the needs of communities, governmental agencies, and construction firms. Deke reports that along the way he became the father of four children and that the oldest, Albert Dekin III, is a member of the Dartmouth class of 1987.

Ray Newell continued his studies in anthropology at the University of London and received his Ph.D. in prehistoric archaeology in 1970. At about the same time, he became a research archaeologist with the Biological/Archaeological Institute of the Rijkuniversiteit at Groningen in the Netherlands and, except for periods spent with the Alaskan pipeline project and as a visiting lecturer at another university, has continued this association ever since. Field studies have taken Ray to "digs" in such diverse geographic locations as Newfoundland, Wales, West Germany, and Denmark, and he is considered an authority on the Middle Stone Age or Mesolithic period of western Europe.

Ray and Deke had an opportunity to renew their Dartmouth friendship when they worked together on a major project that lasted from 1981 through 1984. The two were named as co-principal investigators of an international team of scholars undertaking major excavations in advance of utility construction in the vicinity of Barrow, Alaska. At a site by the name of Utqiagvik village, discovery was made of a partly frozen sod and wooden house that had become sealed in a sudden upheaval of sea ice as many as 400 years earlier. Two extremely well-preserved frozen bodies and three skeletons were found intact along with the household articles of this prehistoric [i.e., prior to European contact] family in the original resting place. The biological and cultural work of the project has been described as extraordinarily significant and it is unquestionably a major contribution to the study of man in the Arctic region.

Skip Koolage is a professor of anthropology at the University of Manitoba. He says he originally had no intention of becoming an anthropology major, but signed on for a part-time job at the museum in Wilson Hall and found himself getting "hooked" on the subject. He completed work on his Ph.D. in 1970 at the University of North Carolina and accepted a teaching position in Canada, where his studies have concentrated on the Inuit cultures in the northern part of the country. Skip says he "prefers live bodies, unlike Deke and Ray," and therefore confines his efforts to current Eskimo culture. He works closely with colleagues from the university's medical school and much of his time is spent in conversations with "old geezers" he flies to visit in remote wilderness areas. Skip says the trend of Dartmouth anthropologists toward arctic studies may be due to the influence of Professors Harp and McKennan as well as the resources and inspiration provided undergraduates by the Stefansson Collection at the College.

Having at last reached the end of our survey of 11 classmates, the answer to the question of what anthropology majors turn out to be seems fairly simple. Briefly stated, it is "all sorts of things;" we have seen that this group of '65s has produced a salesman, a journalist, a priest, a doctor, and even college anthropology professors. The only uniting theme was that all felt their choice of majors was an excellent one and that this feeling increases with the passage of time. Perhaps it is unfortunate that most of us do not learn answers to such questions much earlier in life.

David K. Shipler '64 is the author of the book Arab and Jew: Wounded Spirits in a Promised Land, which was recently published byTimes Books of New York. Shipler formerly wasa bureau chief for the New York Times in Jerusalem and Moscow and is now a political reporter for the Times' Washington bureau.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

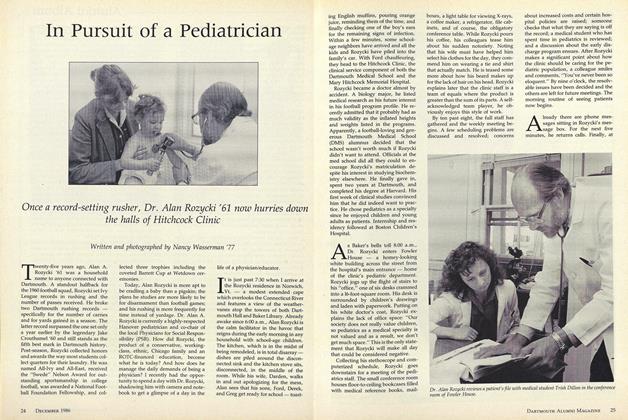

FeatureIn Pursuit of a Pediatrician

December 1986 By Nancy Wasserman '77 -

Feature

FeatureLawyers, Liberal Arts, and the Cold War

December 1986 By Weyman I. Lundquist '52 -

Feature

FeatureRichard Hovey: The Incomplete Arthurian

December 1986 By Daniel P. Nastali -

Feature

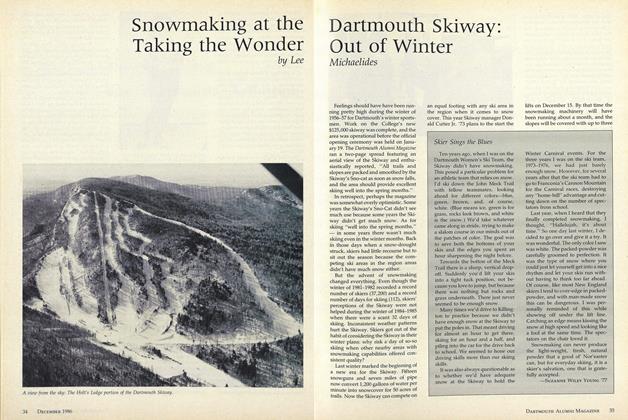

FeatureSnowmaking at the Dartmouth Skiway: Taking the Wonder Out of Winter

December 1986 By Lee Michaelides -

Article

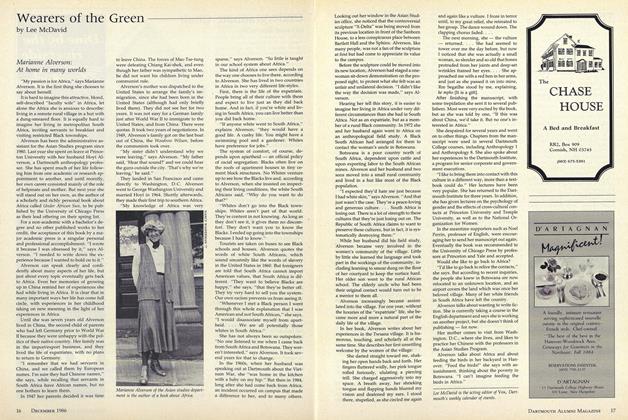

ArticleMarianne Alverson: At home in many worlds

December 1986 By Lee McDavid -

Article

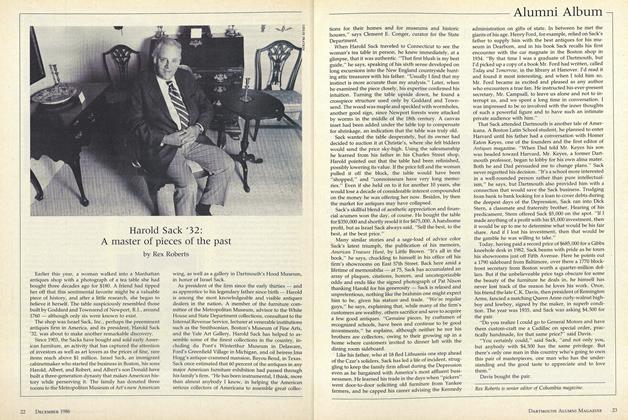

ArticleHarold Sack '32: A master of pieces of the past

December 1986 By Rex Roberts

Bruce D. Jolly

Class Notes

-

Class Notes

Class Notes1909

APRIL 1970 By BERTRAND C. FRENCH, STANLEY W. LEIGHTON -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1930

March 1935 By Bldg., Hanover, N. H -

Class Notes

Class Notes1940

February 1960 By J. MALCOLM DE SIEYES, DONALD G. RAINIE -

Class Notes

Class Notes2002

Sept/Oct 2009 By J.T. Leaird -

Class Notes

Class Notes1959

FEBRUARY 1964 By RICHARD G. JAEGER, WILLIAM H. DUGGAN JR. -

Class Notes

Class Notes1933

March 1961 By WESLEY H. BEATTIE, GEORGE N. FARRAND