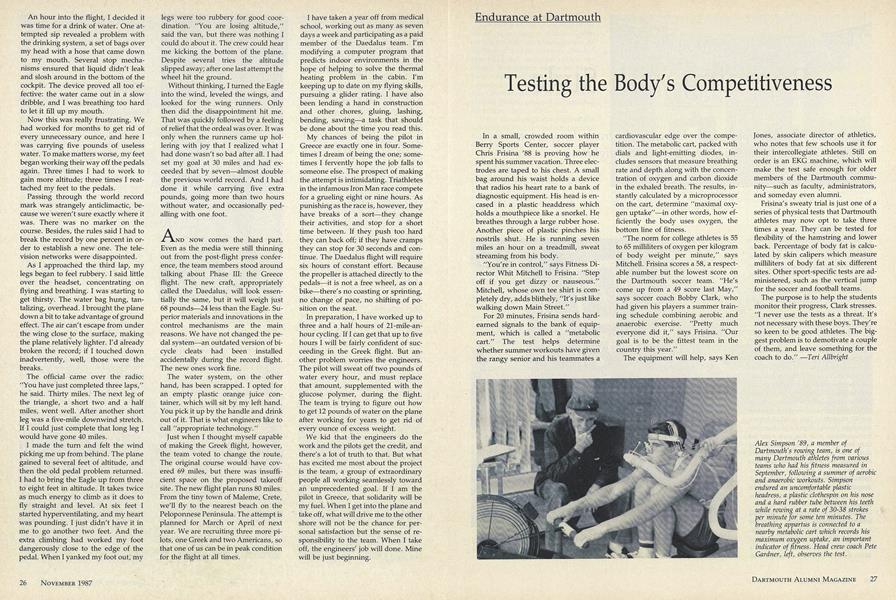

In a small, crowded room within Berry Sports Center, soccer player Chris Frisina '88 is proving how he spent his summer vacation. Three electrodes are taped to his chest. A small bag around his waist holds a device that radios his heart rate to a bank of diagnostic equipment. His head is encased in a plastic headdress which holds a mouthpiece like a snorkel. He breathes through a large rubber hose. Another piece of plastic pinches his nostrils shut. He is running seven miles an hour on a treadmill, sweat streaming from his body.

"You're in control," says Fitness Director Whit Mitchell to Frisina. "Step off if you get dizzy or nauseous." Mitchell, whose own tee shirt is completely dry, adds blithely, "It's just like walking down Main Street."

For 20 minutes, Frisina sends hardearned signals to the bank of equipment, which is called a "metabolic cart." The test helps determine whether summer workouts have given the rangy senior and his teammates a cardiovascular edge over the competition. The metabolic cart, packed with dials and light-emitting diodes, includes sensors that measure breathing rate and depth along with the concentration of oxygen and carbon dioxide in the exhaled breath. The results, instantly calculated by a microprocessor on the cart, determine "maximal oxygen uptake" in other words, how efficiently the body uses oxygen, the bottom line of fitness.

"The norm for college athletes is 55 to 65 milliliters of oxygen per kilogram of body weight per minute," says Mitchell. Frisina scores a 58, a respectable number but the lowest score on the Dartmouth soccer team. "He's come up from a 49 score last May," says soccer coach Bobby Clark, who had given his players a summer training schedule combining aerobic and anaerobic exercise. "Pretty much everyone did it," says Frisina. "Our goal is to be the fittest team in the country this year."

The equipment will help, says Ken Jones, associate director of athletics, who notes that few schools use it for their intercollegiate athletes. Still on order is an EKG machine, which will make the test safe enough for older members of the Dartmouth community such as faculty, administrators, and someday even alumni.

Frisina's sweaty trial is just one of a series of physical tests that Dartmouth athletes may now opt to take three times a year. They can be tested for flexibility of the hamstring and lower back. Percentage of body fat is calculated by skin calipers which measure milliliters of body fat at six different sites. Other sport-specific tests are administered, such as the vertical jump for the soccer and football teams.

The purpose is to help the students monitor their progress, Clark stresses. "I never use the tests as a threat. It's not necessary with these boys. They're so keen to be good athletes. The biggest problem is to demotivate a couple of them, and leave something for the coach to do."

Alex Simpson '89, a member ofDartmouth's rowing team, is one ofmany Dartmouth athletes from variousteams who had his fitness measured inSeptember, following a summer of aerobicand anaerobic workouts. Simpsonendured an uncomfortable plasticheadress, a plastic clothespin on his noseand a hard rubber tube between his teethwhile rowing at a rate of 30-38 strokesper minute for some ten minutes. Thebreathing appartus is connected to anearby metabolic cart which records hismaximum oxygen uptake, an importantindicator of fitness. Head crew coach PeteGardner, left, observes the test.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

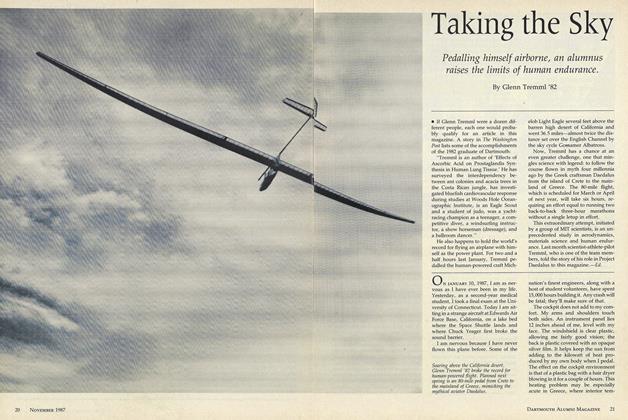

FeatureTaking the Sky

November 1987 By Glenn Tremml '82 -

Feature

FeatureAfter Iran: Can We Have a Foreign Policy?

November 1987 By Stephen Bosworth '61 -

Feature

FeatureAre Conservatives Being Silenced?

November 1987 By Lee Michaelides -

Feature

FeatureRooming with Style

November 1987 By Karen Endicott -

Feature

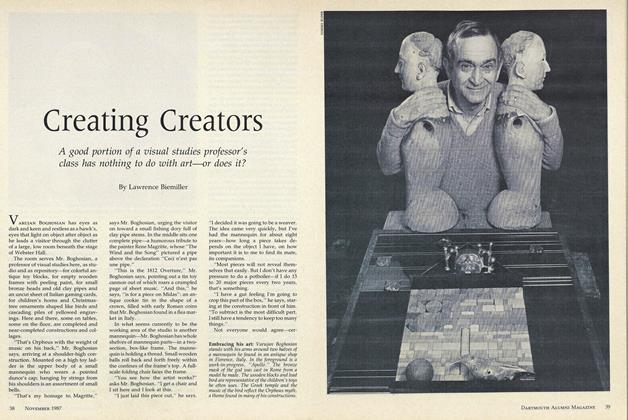

FeatureCreating Creators

November 1987 By Lawrence Biemiller -

Feature

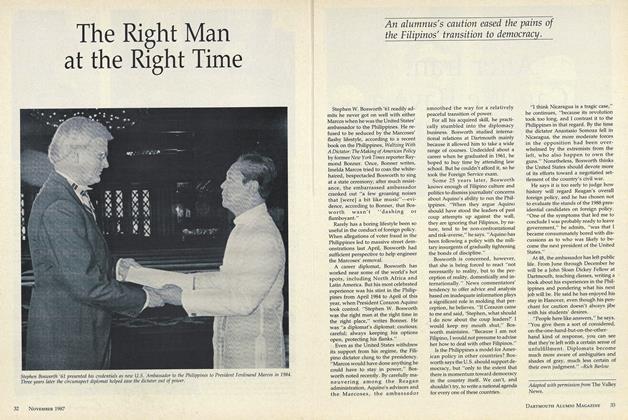

FeatureThe Right Man at the Right Time

November 1987

Teri Allbright

-

Article

ArticleClovers Bring Good Luck to Octogenarian

MARCH 1983 By Teri Allbright -

Article

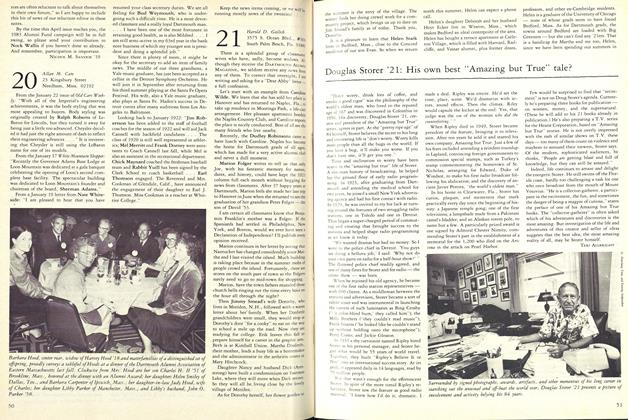

ArticleDouglas Storer '2l: His own best "Amazing but True" tale?

APRIL 1983 By Teri Allbright -

Article

Article"Statistical voyeurism": a peep at the class of '58

MAY 1983 By Teri Allbright -

Article

ArticleLarry Huntley '50: A lifetime of "affirmative" minis try

November 1983 By Teri Allbright -

Feature

FeatureHeeding the Beat of a Different Drummer

SEPTEMBER 1987 By Teri Allbright -

Article

ArticleThe '68 Who Runs the Supreme Court Building

SEPTEMBER 1988 By TERI ALLBRIGHT

Features

-

Feature

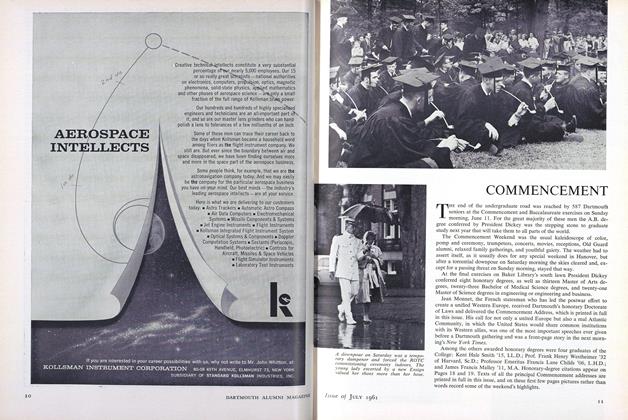

FeatureCOMMENCEMENT

July 1961 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryA Return to Dartmouth

MAY 1984 By Brian W. Ford '67 -

Feature

FeatureRockefeller Center: the ideal of reflection and action

June 1981 By Donald McNemar -

Feature

FeatureIT'S BAD

APRIL 1989 By Edward C. Ingraham '43 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryA Night Out on the Net

December 1994 By Jay Heinrichs -

Feature

FeatureA Life in the Wild

May/June 2001 By NELSON BRYANT ’46