Art Imitates Life

Jean Hanff Korelitz ’83 discusses her latest novel, The Devil and Webster, and how Dartmouth influenced her story.

MAY | JUNE 2017 LISA FURLONGJean Hanff Korelitz ’83 discusses her latest novel, The Devil and Webster, and how Dartmouth influenced her story.

MAY | JUNE 2017 LISA FURLONGThe Devil and Webster is not the first book Korelitz has set on a campus. Admission, published in 2009 and later made into a movie starring Tina Fey, was set at Princeton, where her husband, poet Paul Muldoon, teaches and where she researched the book by being an outside reader for the admissions office. For this book, in which her college has a female president, Korelitz spent time with a couple of presidents. But research takes a writer only so far, the former DAM intern acknowledges. Korelitz told DAM in a 1983 interview about the creative writing class she took spring of her senior year: “The teacher pointed out that in fiction you can make things up. Angels sang.”

Your book will strike readers as prescient given that a key plot element is denial of tenure to a popular, minority professor—an issue that roiled the Dartmouth campus last spring, well after your book was written.

My husband has this theory that when you’re writing the right thing, the world just kind of bends to your will, and suddenly every time you open Dartmouth Alumni Magazine or The New York Times you see that reflected.

The day after I sent my first draft to my editor, I picked up The New York Times and there was my book on the front page. It was Yale [where faculty response to student outrage over a Halloween party was seen as insulting to minority students, who also decried a shortage of minority faculty] and the University of Missouri [where minority students claimed they were treated disrespectfully], but very much my story. At the University of Missouri there was even an incident in a basement where somebody had written in excrement [something that also takes place in The Devil and Webster].

Another issue explored in your book is the treatment of transgender students. Why did you decide to incorporate that?

I had been reading about that beforehand. One of the college presidents who let me kind of follow them around for a day was Debora Spar at Barnard. The day I spent in her office, that’s all they talked about. That is a huge issue, especially for the women’s colleges right now: how to deal with transgender students.

Webster, your fictional college, has much in common with Dartmouth. How did you decide which Dartmouth elements to include?

Well, I’m really fascinated by Dartmouth’s history and position in the political and educational landscape. If one idea that’s lurking around this novel is capitulation— whether it’s personal capitulation or political capitulation or any of the capitulations that we all practice as we go through our lives—Dartmouth had this moment, in the early 1970s, in which we could have gone one way, but we went another.

Can you elaborate on that?

There was a moment in the early 1970s, when women were admitted, minorities were beginning to turn up in greater numbers and Kemeny rededicated the College to educating Native Americans—its original purpose. When Native Americans turned up on campus, and they found their presence inconsistent with the presence of the Indian symbol, the symbol was eradicated. So a great deal of change in a short period of time, but taking all of the change to its ultimate destination would have meant getting rid of the fraternities. And that was the moment when alumni basically said, “This far, no further.” And the College—well, agreed might be one way to put it. Capitulated would be another.

Williams College did take that step when it became clear that the fraternities were not consistent with an intellectual and academic environment. They made their fraternities into dormitories.

Basically, everything that Dartmouth has tried to do, from that moment in the 1970s—the proposed student life initiative and the housing clusters—has been a Band-Aid on the fact that we didn’t get rid of the fraternities. It’s the wound the College never opened up and let heal. Two generations later, we’re still trying to compensate for the Animal House image.

Is it too late to heal the wound?

I don’t know how it can be fixed. I’m sure there are many people out there who’d say, “There’s nothing to fix. Everything is great.” But I have a son applying to college right now and he wouldn’t apply to Dartmouth, even though I begged him to, because he said, “It’s a fraternity school and they all just get drunk.” Multiply that by all of the kids who aren’t applying and it’s a problem.

I say this with great love for the College and with gratitude for the education I got and the friends I made there. It’s still a world-class institution and it’s beautiful beyond compare. It’s full of brilliant people, amazing faculty. Is it everything it could be? No.

Is there any particular reaction you would like readers to have to The Devil and Webster?

As always, I hope people will find it an intellectually rigorous read. And I hope they’ll be surprised by the plot twists. If you’re like me, while you’re reading your brain is already saying, “Well, I’m wondering if this is going to happen, or if that’s going to happen.” If a writer can pull off a real surprise for a reader like that, you’re doing pretty well.

Is there anything you want to tell readers about the book without giving away the plot?

It’s not Dartmouth, it’s Webster. But I would hope that my affection for the College is part of Webster. My concerns about the College are also part of Webster. But it’s fiction.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

Cover StoryMaster of the Game

MAY | JUNE 2017 By Jake Tapper ’91 -

Feature

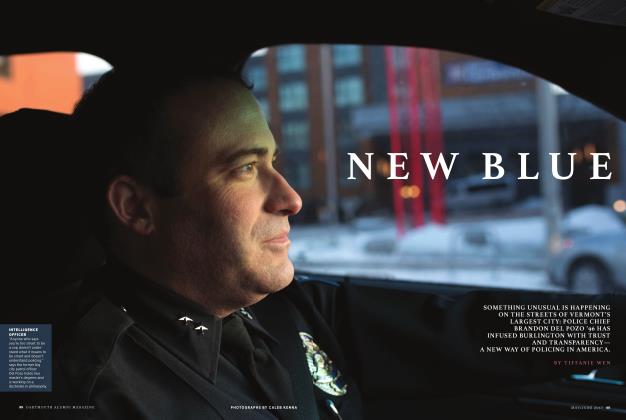

FeatureNew Blue

MAY | JUNE 2017 By TIFFANIE WEN -

Feature

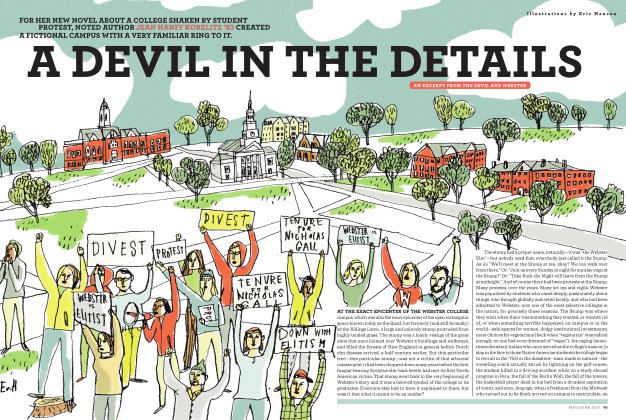

FeatureA Devil in the Details

MAY | JUNE 2017 By Jean Hanff Korelitz ’83 -

Feature

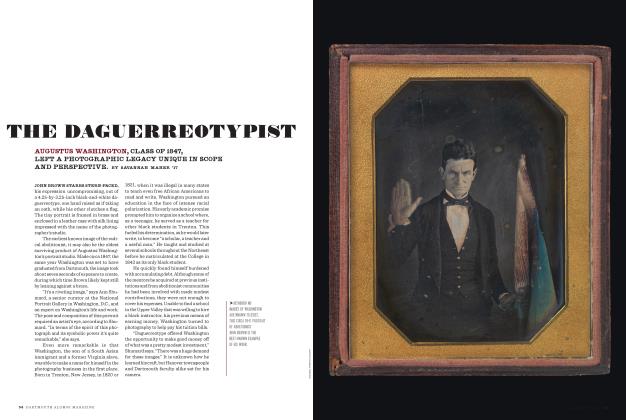

FeatureThe Daguerreotypist

MAY | JUNE 2017 By SAVANNAH MAHER ’17 -

Personal History

Personal HistoryMeryl, Overrated?

MAY | JUNE 2017 By DENIS O'NEILL ’70 -

Politics

PoliticsRace and Republicans

MAY | JUNE 2017 By Matthew Mosk ’92

LISA FURLONG

-

Continuing Education

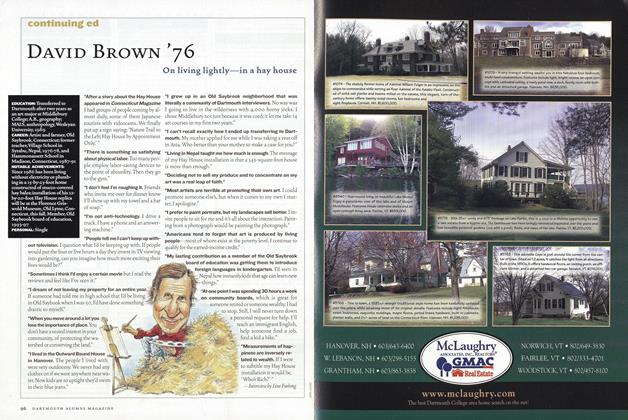

Continuing EducationDavid Brown '76

Jul/Aug 2004 By Lisa Furlong -

Continuing Education

Continuing EducationMortimer Mishkin ’46

July/August 2011 By Lisa Furlong -

CONTINUING ED

CONTINUING EDEric Berlin ’89

MARCH | APRIL 2017 By LISA FURLONG -

CONTINUING ED

CONTINUING EDMatt Klentak ’02

JULY | AUGUST 2018 By LISA FURLONG -

CONTINUING ED

CONTINUING EDDavid Shribman ’76

SEPTEMBER | OCTOBER 2018 By LISA FURLONG -

CONTINUING ED

CONTINUING EDSARAH JACKSON-HAN '88

NOVEMBER | DECEMBER 2025 By Lisa Furlong

Features

-

Feature

FeatureThe Topic: Third Century Fund

NOVEMBER 1967 -

Cover Story

Cover Story"Be Prepared For The Unexpected"

Mar/Apr 2009 -

Feature

FeatureANGELA PARKER

Nov - Dec -

Feature

FeatureThe Philosophy of Culture

DECEMBER 1966 By ALBERT WILLIAM LEVI '32 -

Feature

FeatureAlumni College Retrospective

MAY 1983 By Jean Dalury -

Feature

FeatureSCHOOLMARMS, GRAMMARIANS and ANARCHISTS

MARCH 1959 By ROBERT S. BURGER