In Her Element

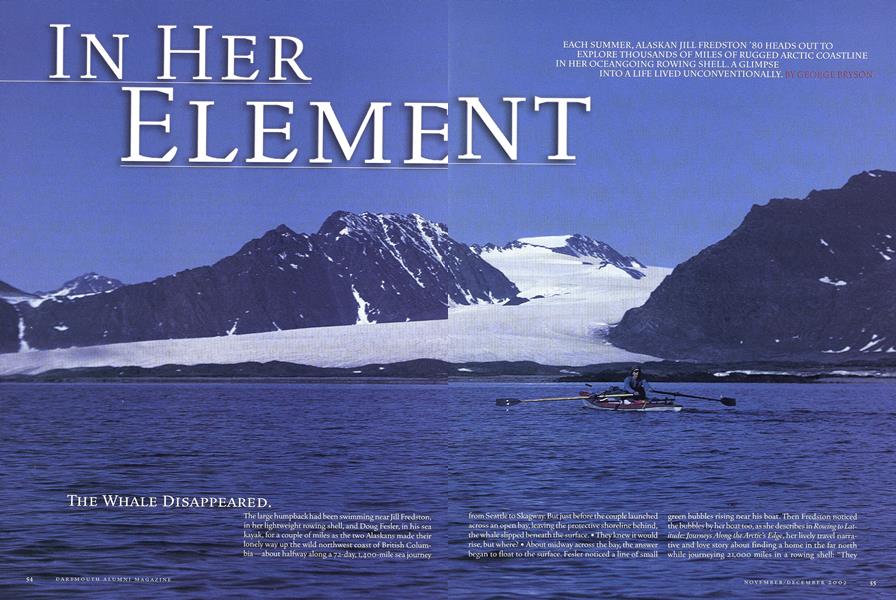

Each summer,Alaskan Jill Fredston ’80 heads out to explore thousands of miles of rugged Arctic coastline in her oceangoing rowing shell. A glimpse into a life lived unconventionally.

Nov/Dec 2002 GEORGE BRYSONEach summer,Alaskan Jill Fredston ’80 heads out to explore thousands of miles of rugged Arctic coastline in her oceangoing rowing shell. A glimpse into a life lived unconventionally.

Nov/Dec 2002 GEORGE BRYSONEACH SUMMER, ALASKAN JILL FREDSTON '80 HEADS OUT TO EXPLORE THOUSANDS OF MILES OF RUGGED ARCTIC COASTLINE IN HER OCEANGOING ROWING SHELL. A GLIMPSE INTO A LIFE LIVED UNCONVENTIONALLY.

THE WHALE DISAPPEARED. from Seattle to Skagway. But just before the couple launched across an open bay, leaving the protective shoreline behind, the whale slipped beneath the surface. • They knew it would rise, but where? • About midway across the bay, the answer began to float to the surface. Fesler noticed a line of small green bubbles rising near his boat. Then Fredston noticed the bubbles by her boat too, as she describes in Rowing to Latitude: Journeys Along the Arctic's Edge, her lively travel narrative and love story about finding a home in the far north while journeying 21,000 miles in a rowing shell: "They extended from the port side of Doug's kayak toward me in a 30-foot arc. Then Doug noticed that there were also bubbles advancing to ward him from the starboard side. I felt the first flush of fear...." The large humpback had been swimming near Jill Fredston, in her lightweight rowing shell, and Doug Fesler, in his sea kayak, for a couple of miles as the two Alaskans made their lonely way up the wild northwest coast of British Columbia—about halfway along a 72-day, 1,400-mile sea journey

What seemed to be encircling them, they realized, was the 60- foot-wide bubble net that a humpback exhales to corral a school of fish just before the whale swallows it whole. The rowers were sit- ting on the bull's-eye.

"Aghast, we saw a clear bubble, easily the size of a compact car, rising below the little bubbles and directly underneath Doug's boat. Just under this lens of whale breath, and no more than 15 feet below the surface, the dark curve of the whale's body rocketed straight toward Doug like an elevator exploding from its shaft.

"'Move!' Doug yelled—unnecessarily, as I was already throttling up to full power. With a whoosh, the whale burst from the water exactly where our boats had been a stroke or two before, right through the ripple marks left by our blades."

Most Alaskans know Fredston, 44, and Fester 56, in their winter guise. As the state's foremost avalanche experts, they rush to the scenes of major snow slides to help find the missing and save lives. The husband — and — wife team teaches students from around the world at their Alaska Mountain Safety Center in Anchorage, and together they've written a guidebook on avalanche awareness titled Snow Sense:A Guide to Evaluating Snow Avalanche Hazard.

But each year when summer arrives, Fredston and Fesler embark on a different life together, packing their little boats with a few months' worth of food and supplies—and a marine radio—and leaving Anchorage behind to explore some wild northern watercourse.

In 1986 it was the fiord-like coastline between Washington and Alaska. In 1987 it was a 2,000-mile journey down the Yukon. In 1988 it was the Chukchi Sea around the northwest shoulder of Alaska.

Other summers have found them rowing and paddling up the ancient coast of eastern Labrador, down the length of Canada's MacKenzie River, across the top of the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge, back along the Alaska Peninsula—where they glimpsed more than a hundred brown bears—as well as trips abroad to Greenland, Spitsbergen and the coasts of mainland Norway.

In 2001 Fredston played landlubber as she toured the country promoting her book. At a Syracuse, New York, bookstore, a woman in the audience had just one question for the author: "How do you spend so much time with your husband?"

Relaxing in the comfortable wood-heated home the couple built in the Chugach foothills outside Anchorage, Fredston laughs at the memory. "The reaction I've gotten to this book so far is kind of funny."

She began it five years ago as a gift to her mother, who was then just beginning to battle cancer. It starts with Fredston recalling her childhood on Long Island Sound, her schooling at Dartmouth—including some collegiate rowing (see "The Pull of Rowing," page 58)—and graduate studies in glaciology at Cambridge University in England. Then it covers Fredston's arrival in Alaska, where she sought a place to apply all her book learning.

"I was very sure of myself, with opinions as absolute as pure elements," she writes. "The best mates were close in age. Love was a matter of conscious choice. Divorce was failure. Vulnerabilities were to be hidden. Aging was to be dreaded. I summed up peoples assets and liabilities as I perceived them, making snap judgments based upon appearance, educational background or career path."

Then along came bearded, middle-aged, divorced Fesler, with his checkered high school education and practical wisdom, turning all those notions on their head—and Fredston's world began to change.

"I'm not sure I would have had the courage to fall in love with Doug anywhere but Alaska. Alaska diminished the risk and made everything seem possible," Fredston writes. "'You're going to build a house,' people would say. 'Great! Where? When?' They never asked, 'How are you going to build a house when you don't know a thing about vapor barriers, framing a wall, or putting on a roof?' It was as though Doug and Alaska were co-conspirators, each whis pering in my ear: There are no boundaries here. Throw away your lesson plans, the limits are what you make them."

Exploring those limits as a late-blooming writer, Fredston has yet to bump into many boundaries, winning an enviable first-book contract with North Point Press (a division of Farrar, Straus and Giroux) as well as being honored as a "Great New Writer" selection by Barnes & Noble Booksellers.

Beyond the travel and natural history, Rowing to Latitude is a love story, as Fredston describes her evolving relationship with her husband and the landscape. "Labrador was a miracle to us," Fredston told a recent slide-show audience in Anchorage, "because you have this seething eastern seaboard population not very far away, and yet we went 23 days without seeing a boat, a plane, a piece of garbage, anything.

"We had this one morning when Doug just woke me with a kiss and a finger on his lips and I heard this gentle sighing and we looked out the tent door and there were 15 caribou ringed around us as though we were the camp fire." But Fredston's book is mostly about the sport she adores.

"What I love about rowing is that it's a continuous motion," she says. "There's no beginning and there's no end to any stroke. I really have this feeling when I'm rowing well that I'm creating visual music."

Maybe it's a question of perspective.

For their first 13,000 miles traveling together, Fredston faced backward, rowing her modified single, with Fesler paddling his kayak and usually trailing Fredstons mechanically more efficient boat, even though it carried more than half the gear. The kayak had some advantages, moving more nimbly in waters clogged with pan ice, while sculling in the single became more difficult in choppy seas. But Fredstons ease of rowing in normal conditions finally won Fesler over.

Her boat of choice began as a 19-foot-5-inch, Kevlar-hulled kayak. Its Canadian builder then equipped it with an open cockpit in the center with a sliding seat and outriggers, and closed hatches fore and aft capable of storing about 100 days of dehydrated food.

Laying out absolutely everything they're going to eat for the whole summer when they gear up at the beginning of a trip can be a little demoralizing, Fredston says.

"But it's also liberating. You know you aren't going to the grocery store. And there is a tremendous focus that comes with simplicity. It's not having too many choices. You basically have everything you need."

Learning to live the way you want to live was an integral part of her Dartmouth experience, Fredston says. A visit to campus last February, as part of her book tour, brought that realization home.

"A lot of the rowing team was there at the talk, and I felt a part of me was looking at myself sitting in that auditorium years ago as a student," she says. "Dartmouth sort of continued this idea of how you put together a life. How you compose a life."

Lightweight coach Dick Grossman recalls how in 1976 two students—both novice rowers—rowed for three consecutive 45- minute sessions when all that was required was a single session. "One of them focused on speed and went on to win a silver medal in the Olympics," recalls Grossman. "The other focused on distance." The speed queen was national champion sculler Carlie Geer '8O. The distance rower was her roommate, Fredston.

Fredston majored in geography and environmental science. She was a member of the Dartmouth Outing Club, performed volunteer work for the Environmental Protection Agency and traveled to Sweden and the Philippines on foreign study programs.

All of which whetted her appetite to study and work and travel some more.

But why Alaska?

"We like wild country," Fredston answers simply. "And for the most part, the wild country is going to be where there's the fewest people. And that's going to be where the weather has its moments."

You can trust an old oarsman on that one. The weather does have its moments—and the sea has its whales—when you're rowing to latitude.

Fredston rows the east coast of Spitsbergen, Norway.

"IT WAS AS THOUGH DOUG AND ALASKA WERE CO-CONSPIRATORS, EACH WHISPERING IN MY EAR: THERE ARE NO BOUNDARIES HERE. THROW AWAY YOUR LESSON PLANS, the limits are what you make them."

GEORGE BRYSON is a feature writer for the Anchorage Daily News andau- Lights: The Science, Myth and Wonder of Aurora Borealia

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureThe Gatekeepers

November | December 2002 By JACQUES STEINBERG ’88 -

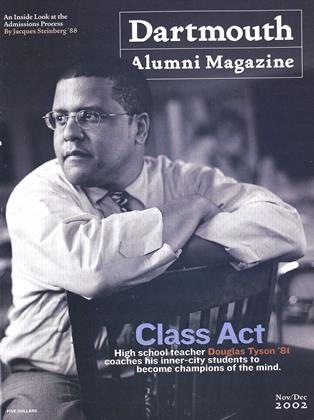

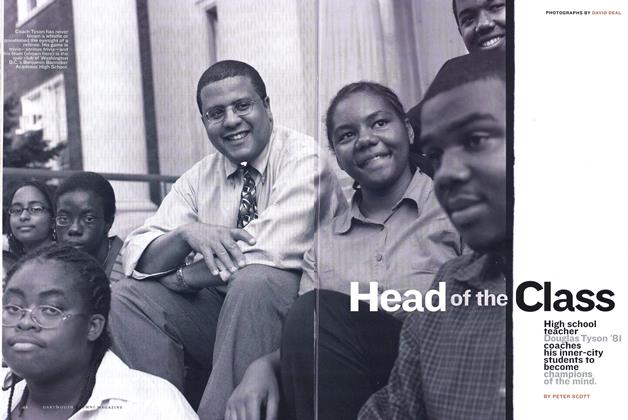

Cover Story

Cover StoryHead of the Class

November | December 2002 By PETER SCOTT -

Faculty Opinion

Faculty OpinionThe Iraq Question

November | December 2002 By Daryl G. Press -

Classroom

ClassroomThe Art and Science of Group Dynamics

November | December 2002 By Karen Endicott -

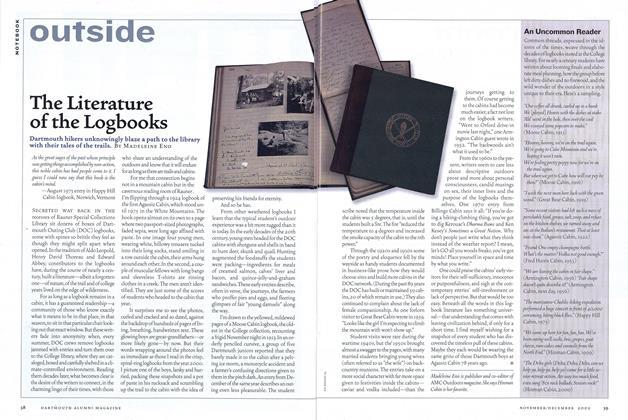

Outside

OutsideThe Literature of the Logbooks

November | December 2002 By Madeleine Eno -

Article

ArticleSeen & Heard

November | December 2002

Features

-

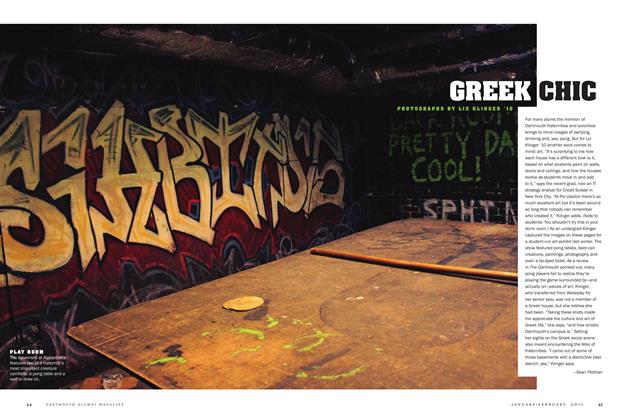

Feature

FeatureGreek Chick

Jan/Feb 2011 -

Feature

FeatureSMITH

JUNE/JULY 1984 By Brad M. Hutensky '84 -

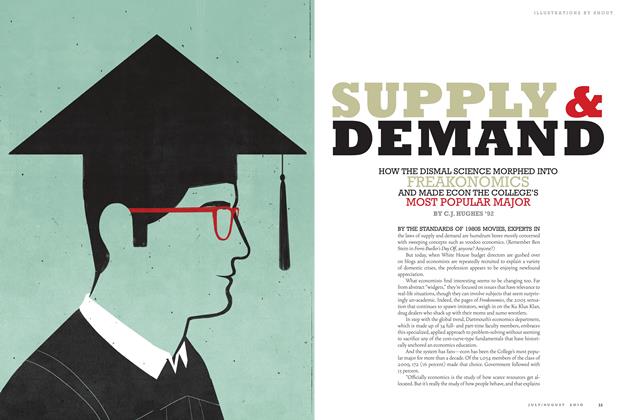

Cover Story

Cover StorySupply & Demand

July/Aug 2010 By C.J. Hughes ’92 -

Feature

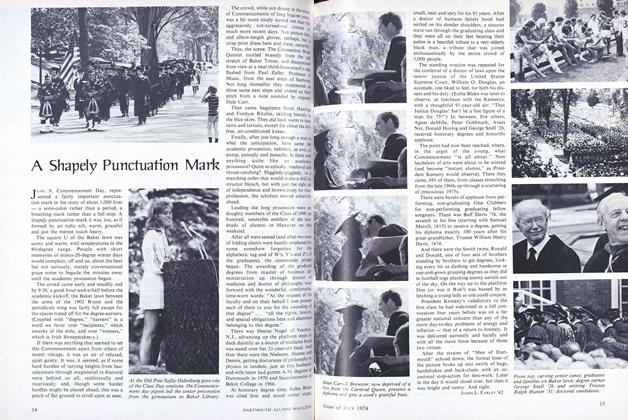

FeatureA Shapely Punctuation Mark

July 1974 By JAMES L. FARLEY '42 -

Feature

FeatureFour-Star Summer

October 1959 By JIM FISHER '54 -

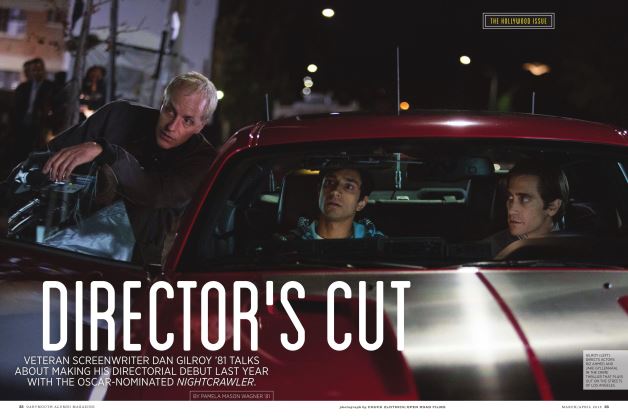

FEATURE

FEATUREDirector’s Cut

MARCH | APRIL By PAMELA MASON WAGNER ’81